Troubadours, Dissidents, & Legends

Posted By Fullmoon Ancestry On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,492 words

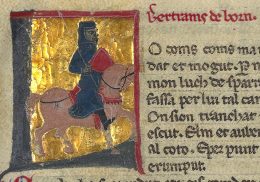

Sometimes the myths and legends of a person overshadow their real characteristics. Yet both aspects are important. Without the real-life person and his actions, the myths and legends of that person would never be created. Without those embellished myths and legends, many historic individuals might have been ignored or forgotten over time. One historical figure I have thought about the last few months is the 12th century Occitan troubadour Bertran de Born. While the past few centuries have judged him negatively, the real-life characteristics surrounding this troubadour can give us insight on how we can reclaim our communities, culture, and identity.

Troubadours were composers and performers of Old Occitan [1] poetry during the late Middle Ages [2]. This tradition began in the late 11th century in Occitania [3] (modern-day southern France) and grew in popularity throughout Europe over the next following centuries. The original lyrics of troubadour poetry dealt mainly with themes of chivalry and romance. Eventually, troubadours started writing about other topics such as politics, society, and warfare. One of the most famous troubadours of this time period was Bertran de Born.

Born was one of the major Occitan troubadours [4] of the twelfth century. His catalog consisted mostly of sirventes [5] (“service songs” in Old Occitan) which were poems that added propaganda and political lyrics into pre-existing melodies. He also wrote planhz (“lamentations”) which were poems that eulogized deceased kings and princes. The oldest surviving work of Born is from 1181, but it appears that he was already a well-renowned poet by that time. By 1182, he was present at Henry II of England [6]‘s court in the French town of Argentan.

That same year, Born started writing poems in support of Henry II’s son Henry (known as Henry the Young King [7]). Born wrote songs encouraging the younger Henry to rebel against his brother, Richard I. Unfortunately, Henry the Young King died on a campaign against his father and brother in 1183. As punishment for encouraging the young Henry’s rebellion, Richard took Born’s castle and gave it to Born’s brother. Almost immediately, Bertran wrote a eulogy poem for Henry the Young King titled Mon chan fenisc ab dol et ab maltraire. King Henry II was so moved by Bertran’s poem for his son that he returned the castle to the poet.

Born eventually reconciled with Richard, and after Richard became King of England in 1189, Born accompanied him on the Third Crusade. Born wrote about his experiences from this crusade and it was a reoccurring theme throughout his career. After returning to France, he started writing poetry encouraging (some would say “inciting”) Richard to go to war against Philip II of France. After Richard was accused of assassinating Conrad of Montferrat, Born wrote a poem praising and exonerating Richard called Ar Ven La Coindeta Sazos.

You can buy Kerry Bolton’s Artists of the Right here [8].

After his second wife died, Born became a monk in 1196 and entered the Cistercian abbey of Dalon in Sainte-Trie, an abbey he gave numerous donations to throughout the years. His last recorded poem was written in 1198. While there is not an official date of his death, Born most likely died in or around 1215, as there is a record of payment for a candle for his tomb.

After a minor resurgence in the late 13th century, the art of the troubadours declined in the 14th century and practically died out by the time of the Black Death in 1348. It is around this time that Born’s legacy started to have negative connotations.

In Dante’s Inferno, the first part of the Divine Comedy, Born is portrayed in a negative manner. Born is punished to live eternally in the eighth circle of Hell, carrying his severed head [9] like a lantern. Dante also compared Born with Ahitophel, a biblical character who incited Absalom to rebel against his father King David. Gustave Doré depicts this in one of his most famous illustrations to the Divine Comedy.

Eleanor Anne Porden wrote an epic poem in 1822 called Cœur de Lion, based on the Third Crusade of the 12th century. Porden portrays Born as a divisive character and goes so far as to blame Born for Richard I’s imprisonment. Born is also depicted negatively in Maurice Hewlett’s novel The Life and Death of Richard Yea-and-Nay. Despite the title of the novel coming from the nickname Born created for Richard I, Hewlett portrays Born as a thief and a fool.

Ezra Pound must have seen something important in Bertran de Born, as Pound was heavily influenced by his poetry and life. Pound translated one of Born’s most popular songs “Be’m Platz Lo Gais Temps De Pascor.” Pound also created several original poems around Born and his works: including Na Audiart (1908), Sestina: Altaforte (1909), and Near Périgord (1915). There are also references made to Born in The Cantos, Pound’s own epic poem.

I first learned about Bertran de Born 18 months ago. The black metal band M8l8th had just released “Удар милосердия / Coup de Grâce,” a 15-minute song broken into three parts. Two of the parts have French lyrics related to Bertrand de Born, sung by Famine of Peste Noire. I was fortunate enough to see this song performed in concert and all the musicians did an amazing job of capturing the atmosphere of the song live on stage. A few days after the concert, I met some representatives from CasaPound. For those unfamiliar, CasaPound is a nationalist organization in Italy that derives its name from Ezra Pound. I asked them if they were familiar with Bertrand De Born, and they told me that they were familiar with the troubadour because Pound wrote so favorably about him in his works.

We can learn a lot from Bertrand de Born. He was politically savvy in his actions, and in the words and metaphors he used in his poetry. He often gave contemporary rulers nicknames in his poetry that had multiple meanings: Henry the Young King was Mariniers (sailor) and Richard I was Oc-e-Non (Yes-and-No). Other troubadours noted that he was able to get away with controversial topics because of his charismatic personality, persuasive arguments, and overall charm. His contemporaries also noted that Born created lyrics and melodies that were catchy and memorable. Despite their controversies, his poems and songs were extremely popular in his time.

We as white advocates have the daunting tasks of rebuilding our culture and our communities. Sometimes the challenges we face seem like the plot to a dystopian science-fiction novel. Our governments are replacing us with non-whites and these non-whites are committing massive amounts of crimes and violence. If we try to speak up or bring awareness about these issues, we are slandered, censored, arrested, and sometimes physically attacked.

We are dissidents. But we are also rebels. We are the ones speaking truth to power. We are the real counterculture. After all, one man’s villain is another man’s hero. Bertran de Born was negatively portrayed for centuries, but all it took were a few poems and translations by Pound to turn Born into a larger-than-life character idolized by musicians and activists.

Most importantly, Bertrand de Born created art. He used the popular medium of his time to influence kings and even shape foreign policy. We often forget just how long the anti-whites have been using various forms of art and entertainment to push their anti-white propaganda. We need our own artists, in all mediums, creating white-positive content. We need writers, painters, filmmakers, and programmers. We need more books, albums, films, and video games. We need to create our own art and support the art our community is creating.

When we create art that expresses our interests and ideas, we slowly rebuild our culture. When we go to concerts, events, and conferences, we start to grow and strengthen our communities. And just as the anti-whites have made the “long march” through the institutions over the decades, we, too, cannot change the culture overnight. It takes time, effort, and finances. Without kings and patrons supporting Bertrand de Born, we might have never read Ezra Pound’s poetry. Without Ezra Pound, I might not have seen one of my favorite bands perform one of my favorite songs in concert.

I hope you consider donating to all the content creators you enjoy watching. I also encourage you to purchase the books, music, and merchandise the artists in our community have created. If nothing else, consider creating some art of your own. Maybe you might create the next song, book, or film that inspires our future generations to stand up for our communities, culture, and white identity. If the troubadours of the past can inspire the dissidents of today, then we can support and inspire the legends of tomorrow.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [10] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.