The Carter-Kennedy Feud of 1980

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,271 words

Jon Ward

Camelot’s End: Kennedy vs. Carter & the Fight that Broke the Democratic Party

New York: Twelve, 2019

The US Presidential Election of 1980 turned into a vicious civil war within the Democratic Party. The conflict centered upon the incumbent President Jimmy Carter and Senator Edward “Ted” Kennedy of Massachusetts. The drama is documented in a fast-paced, well-written book by Jon Ward. While the book’s focus is upon the narrow actions of both Carter and Kennedy, between the lines, one sees that the fight between the two men was part of the price the Democrats paid for endorsing “civil rights” sixteen years earlier with the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

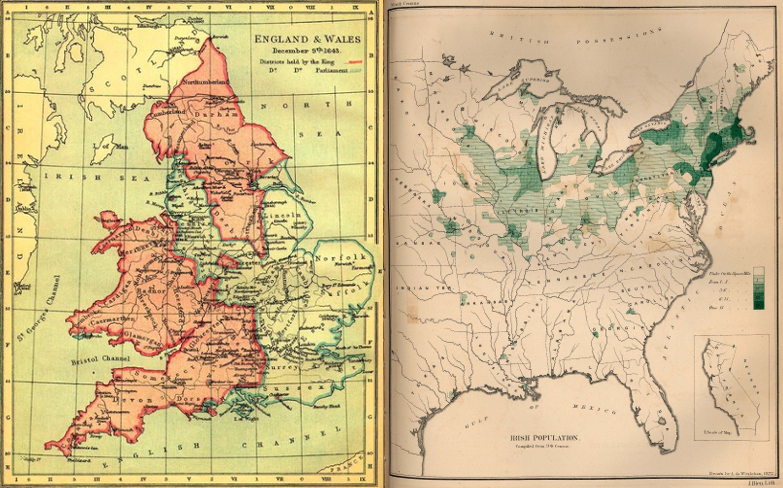

The political split in American politics flows from the civil unrest in the British Isles that put Parliament against the House of Stuart between 1642 and 1688. Roughly speaking, the Republican Party parallels Oliver Cromwell and William and Mary’s faction. This faction is comfortable with complex financial activity; ethnically, it is mostly English or other North Sea/Baltic European, and it is supportive of radical Protestantism. For most of its history, the Democrat’s base of support were those with ties to Stuart’s faction; Southern Protestant whites and Irish Catholics who lived in the Northern United States. There is, of course, plenty of overlap and swing voters. Not every Yankee Protestant has been a Republican, nor every Southerner or Irish Catholic a Democrat, but the basic pattern holds.

Left: Many Southerners trace their ancestry to the regions of England that supported the Stuarts during the English Civil War. Right: The location of Irish in the 1870 US Census. Irish Catholics also supported the Royalist faction during that conflict. In America, the Democratic Party drew its support from the factions that supported the Stuarts during the English Civil Wars and both Jimmy Carter and Ted Kennedy hailed from those groups. President Carter was descended from English Gentry that went to Virginia in the seventeenth century and Kennedy’s Irish Catholic identity is very well known.

From 1932 to 1980, the Democratic Party was the political expression of the American people. Throughout most of that time, they held the White House and both chambers of Congress. Under Franklin Delano Roosevelt, they beat back the monster that was the Great Depression and won World War II. Under Harry Truman, they shaped the way the United States would wage and win the Cold War.

However, all of this came with a fatal flaw. Although the party’s bedrock base supporters were racially aware Southerners and Irish Catholics, the party took blacks into its fold. After 1932, Democratic Party conventions became the central place where “civil rights” advanced. Of course, “civil rights” as it is commonly understood has nothing to do with the rights and duties of citizens towards their society. In this case, “civil rights” is a policy that gives Africans privileged access to a civilization that they cannot build and cannot maintain.

When whites started to realize the problems with the “civil rights” movement in the 1950s, Jimmy Carter was serving in the submarine fleet of the United States Navy. After his father died of cancer unexpectedly, Carter returned to run the family farm. Although the farm had no running water or electricity in Carter’s childhood, the Carter family was not entirely poor. They occupied a niche that traced back to the British aristocratic cavaliers who migrated to Virginia and thence southwards. Carter’s father was something like an English Lord, whose agricultural and business activities supported an entire community. Carter realized that his father lived a richer life as a Georgia planter than he was living as a sailor.

You can buy Greg Hood’s Waking Up From the American Dream here. [1]

Carter was honorably discharged from active duty and returned home in 1953. Over the next ten years, Carter grew his farming business and then became a Georgia State Senator in 1963. In 1966, Carter sought to win the Governorship when another Georgia politician, Bo Callaway, dropped out of the Democratic Party to become a Republican (an event that demonstrated the hollowing out of the Democrats following “civil rights”). Carter lost, but showed he had a considerable following.

After the campaign of 1966, Carter had a spiritual awakening and became influenced by the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr (1892-1971). He ran for Governor in 1970 and won by taking a populist stance, as well as appealing to the segregationists in his state. As soon as he took office, Carter addressed his supporters and expressed his support for “civil rights.” Observers say there was an audible groan in the audience when he stated it was time to end racial discrimination.

The stars had lined up for Carter. He was a Democrat when the party still had a considerable following in its traditional white core. He was a racial integrator at a time when such a policy was a winning strategy, and he was an Evangelical Protestant at a time when that community was becoming organized politically but had no political home in either party. The nation was also frustrated by the Vietnam War and Watergate scandal. In 1976, Carter was elected President.

Meanwhile, Ted Kennedy had become the head custodian of his family’s considerable political legacy. The Kennedy mystique was enormously powerful in the Democratic Party. In 1964, when Robert Kennedy addressed the Democratic Convention, the delegates wept and clapped for nearly a half an hour before he could give his speech. Ted had used this mystique to become a Senator from Massachusetts, and JFK’s former aides helped Ted out after he killed a young woman who was not his wife in a suspicious car accident in Chappaquiddick, Massachusetts.

The Carter Administration’s Nosedive & the Road to the Kennedy-Carter War

Although it was not apparent at the time, Carter came to the Presidency with considerable weaknesses. He had no agenda to enact. His campaign rested upon the fact he was an outsider and the idea that he was as honest as the American public. It was very vague. Ward writes:

The more obvious reason for Carter’s vagueness was that he was a master at assembling a diverse coalition of supporters by avoiding offending each of them. Speechwriter Bob Shrum, who quit the Carter campaign. . . after working for him only nine days, said in a letter to Carter that his strategy was “designed to conceal your true convictions, whatever they may be.” Shrum’s bitter conclusion: “I am not sure what you believe in, other than yourself.” [1] [2]

Carter also had no real political base — a situation caused in no small part by the Democratic Party’s support for “civil rights.” Irish Catholics and Southern Whites were shifting their allegiance.

Meanwhile, Carter was doing himself no favors. All autopsies of Carter’s leadership style say the same things. Carter had a poorly organized staff. He also didn’t have a Chief of Staff. [2] [3] Instead, he micromanaged affairs. The arrangement led to many idle staffers unable to handle small problems before they became big ones. Carter’s biggest mistake — and one should really reflect upon this — was that he dealt with Congressmen and other notables by being honest and attempting to persuade them to the rightness of his ideas through logic. What these notables actually wanted was to be given White House cufflinks and rides to their home district in Air Force One. If they were in the same limo as the President, they wanted to sit next to him and tell him their story. Honesty and logic were a distant priority. As a result, Congress became increasingly hostile.

Carter’s presidency entered into a steep, uncontrolled dive when one of Carter’s key staffers, Bert Lance, got embroiled in a media-fueled scandal. Because Carter’s only real agenda item was “honesty,” he was forced to jettison Lance. Losing Lance was a disaster: Carter lost a trusted assistant who gave good advice.

Ted Kennedy decided to run in the Democratic Primary halfway through the Carter Administration. He was nearly forced to do so, as so many Democrats ached for a return to the Kennedy “Camelot” mystique. Unfortunately, by 1978, Ted Kennedy’s intemperance had gotten the best of him. Reports of his drinking and “womanizing” were everywhere, and Chappaquiddick loomed ever larger in the mind of the public. In 1979, CBS newsman Roger Mudd interviewed Kennedy and the results were a disaster. Kennedy bumbled his answers and failed to give a reason why he wanted to be President.

Kennedy’s primary run likewise became a bumble. Kennedy was saddled with JFK’s campaign managers who understood the nominating process at the convention but didn’t understand the new primary system. Kennedy staked his chances on a win in Iowa, but Carter had the caucus there locked up. Kennedy should have labored to win the primaries in his New England stronghold. Kennedy thus attacked Carter at the President’s strongest point.

Kennedy kept at it until the convention, and he severely damaged the Democratic Party in doing so. After it was clear that Carter would be the Party’s nominee, Kennedy gave a speech about the Kennedy “dream” never dying. Carter’s convention speech turned out to be a disaster. He meant to praise Humbert Horatio Humphrey [4], but he misspoke. He praised Hubert Horatio Hornblower instead. The audience was baffled.

Carter had wanted a gesture of unity from Kennedy at the 1980 Convention. Kennedy failed to give it.

Carter attempted to have a show of unity with Kennedy. He wanted to hold hands with Kennedy while they both had their arms raised, but Kennedy was probably drunk — and definitely angry — and he rebuffed the gesture. Carter was humiliated.

“Civil Rights”: The Gateway Drug for the Harder Stuff of Misread Data & Bigger Problems

The public rebuff of the gesture of unity was something Carter should have foreseen. The Kennedys had been cold and hostile when Carter attended an event at the Kennedy Library in Boston. Jackie Kennedy had winced when Carter attempted to kiss her. In light of that, Carter should have not allowed Kennedy a platform at the convention.

The Kennedys were hostile to Carter long before Ted entered the primary race.

Carter was a believer in “civil rights.” In 1976, he had a great many positive experiences with black audiences at various political rallies. The black vote in Florida likewise turned his way several times. In 1976, the Democratic Party made the Florida primary a contest between Carter and the segregationist George Wallace, with the idea that Carter would win and vindicate the “New South.” [5] During the primary for the 1980 election, Carter’s fixers provided money for a Miami-based black group — the James E. Scott Community Association — and they turned out for a straw poll that helped take the wind out of the Kennedy sails.

Unfortunately, those that believe in “civil rights” always misread data. Carter misread events in Iran, so a revolution that could have ended with Ayatollah Khomeini being killed in an “accident” in Paris grew into a short-term hostage crisis and a long-term danger. There is another problem that believers in “civil rights” have. They trade white support for black support of dubious value. Ward:

Whereas white voters from the middle and working-class had seen Democrats as protecting them from powerful business interests from the New Deal era through the 1950s. . . they now saw Democrats as trying to raise their taxes in order to give government benefits to blacks and other minorities, even as plants were closing and jobs were disappearing in the Rust Belt. [3] [6]

Members of the James E. Scott Community Association ended up rioting in the spring of 1980 in Miami after a black who “didn’t do nothing” was killed following a high-speed chase by Miami police. Since 1940, blacks have been tempted to riot whenever there is a Democrat in the White House. Their loyalty to that party gives them the opportunity to carry out a protection racket.

Additionally, no blacks put forward an idea that Carter could use in Iran, or to fight inflation, or to deal with the energy crisis. They could vote after being paid and riot afterward. Meanwhile, the white Evangelical Protestants that had voted for Carter, led by racially Nordic Catholics like Paul Weyrich, organized into a force. And this force abandoned Carter while producing a large amount of metapolitical material.

The Democrats lost the White House in 1980. Carter’s opponent, Ronald Reagan, went on to humiliate Carter in the debates and have a dazzlingly successful presidency. The liberal ideas of Carter and Kennedy became associated with the “naivety and weakness” of Carter and the intemperance of Kennedy. It is not a stretch to claim universal healthcare has probably never been satisfactorily achieved in America due to the failings of both men.

However, there is much to emulate about Carter and Kennedy. Carter’s post-presidency turned out to be wildly successful. His Carter Center has reduced diseases, among other acts of good. Jimmy Carter has also built homes for the poor, and carried out important negotiations with tricky nations like North Korea. Kennedy went on to become a highly regarded Senator — despite his past. He won by taking incremental victories and expanding upon them day after day. Nonetheless, the Democratic Party still embraces “civil rights” and it has become an African, post-colonial failed-party.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [7] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Notes

[1] [8] Page 103

[2] [9] The failure to hire a Chief of Staff was partially political. When Eisenhower asked Truman about a Chief of Staff, Truman replied words to the effect that the President had to “think for himself.” The remarks were in the 1973 book called Plain Speaking — an oral history of Truman’s career.

[3] [10] Page 235