The Birds Or: Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Coronavirus (But Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock & Heidegger), Part Three

Posted By Derek Hawthorne On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled5,153 words

The police are called, and Mitch is asked to meet the sheriff at the Fawcett farm. Some detectives from Santa Rosa are going to join them there. Presumably, Mitch is expected to repeat his mother’s account of finding the corpse of Dan Fawcett, its eyes pecked out by homicidal birds. In any case, Lydia is in no condition to tell the story herself. Mitch and Melanie talk quietly in the kitchen while the latter makes a pot of tea to take to Lydia.

They embrace. “Do be careful, please,” Melanie says, and then they kiss. This sudden display of affection between the pair is somewhat jarring to the viewer, but only because the earlier scene in which they kiss was cut from the film (as discussed in part two [3] of this series). In the absence of that scene, the casualness with which they express affection here is rather touching. It feels as if it is simply a natural and spontaneous result of the way that events have flung the two together. The teasing and sparring have now vanished from their relationship. They seem somehow more mature, and interact as if they have been a couple for some time. In fact, Mitch and Melanie have only known each other for three days (in case the reader has forgotten, they met on Friday and now it is Monday). This is the effect that adversity can have on men and women.

Mitch departs and Melanie carries the tea on a tray into Lydia’s room, which is on the ground floor. Hunter’s screenplay describes Lydia’s room as “cluttered with the mementos of a life no longer valid. There are photographs of her dead husband, souvenirs of trips taken together, bric-a-brac of Mitch’s childhood. Under it all, there is a distinct femininity.” Lydia is lying in bed. This time, she seems rather glad to see Melanie (who calls her “Mrs. Brenner”). Clearly still traumatized by what she had seen at the Fawcett farm, Lydia’s conversation is somewhat scattered. Uppermost in her mind is Cathy’s safety. “I keep seeing Dan’s face,” she says. “They have such big windows at the school. All the windows were broken in Dan’s bedroom. All the windows.” Melanie reassures her that Cathy will be okay, but Lydia is not convinced, and neither are we.

“I’m not usually this way, you know. I don’t fuss and fret over my children,” she says. Given how cold she has been so far in this film, we wish she would fuss and fret a bit more. Lydia realizes that she lacks something, and begins to reminisce about her husband. “When Frank died. . . You see, he knew the children, he really knew them. He had the knack of being able to enter into their world, of becoming a part of them. That’s a rare talent. . . I wish I could be that way.” It now becomes clear to us that Cathy has been so keen on Melanie staying with them because she is seeking something from the younger woman that she cannot get from her mother, though it is clear that she loves her mother well enough.

You can buy Return of the Son of Trevor Lynch’s CENSORED Guide to the Movies here [4]

Hunter writes, “There is another silence. A curious thing is happening in this room. Lydia, for perhaps the first time since her husband’s death, is discussing it with another person. Curiously, the person is Melanie.” Indeed, Lydia now seems to be warming to her. Melanie offers to leave and let her rest. “No. No. . . don’t go yet,” Lydia says. “I feel as if I don’t understand you. And I want so much to understand.” Melanie asks her why. “Because my son seems to be very fond of you,” Lydia answers. “And I’m not quite sure how I feel about it. I don’t know even know if I like you or not.” This is said completely without malice. It is a moment of simple and plain honesty, and it is touching. Melanie insists that it doesn’t really matter whether Lydia likes her or not, though we know that actually it very much matters to Melanie. She has already heard from Annie what Lydia can do to Mitch’s relationships.

“Mitch has always done exactly what he wanted to do,” Lydia says with resignation. Then, in the screenplay but not in the finished film, she adds “That’s the mark of a man.” Of course, she misunderstands her son. He has always done what she has wanted him to do, and thus does not bear the mark of a man. Suggesting that she is dimly aware of her manipulation of him (and of her motivations), Lydia becomes emotional at this point and says, “But you see, I. . . I wouldn’t want to be left alone. I don’t think I could bear to be left alone. Oh, forgive me.” She begins sobbing and Melanie, who is obviously moved, tries to comfort her.

Lydia has confirmed Annie’s analysis of her psychology: she interferes in Mitch’s relationships out of a fear of being abandoned. Nevertheless, as I noted in part one [5], Annie is blind to Mitch’s own complicity in Lydia’s interference, and to Mitch’s weakness. Each of the major characters in the film has been abandoned, in one way or another. In this way, and in one other “metaphysical” way (as I shall argue later), abandonment is a major theme of The Birds.

Lydia is uncharacteristically emotional and volatile in this scene. Much has been made of how the character of Melanie is “broken down” by the film’s end (often coupled with sinister speculations about Hitchcock’s motives toward Tippi Hedren). But more than one character is “broken down” in this film, and Lydia is the first of the women. Her trauma at the Fawcett farm (quite literally a trauma, complete with hysterical reaction) has precipitated a crisis, and now the catharsis has come. Her veneer of cool control has been shattered, and she has been forced to confront herself and her shortcomings. Lydia’s thoughts swing back to Cathy. “Do you think she’s safe at the school?” she asks again, seeking more reassurance. At this point, Melanie offers to go and fetch Cathy from the school, just to be safe. Lydia is effusive in her thanks. Just as Melanie is about to leave the room, Lydia calls to her. “Melanie?” she says, warmly. “Thanks for the tea.”

The setting now shifts to the exterior of the Bodega Bay school, in the middle of the afternoon. We are now in store for what is arguably the film’s most iconic scene [6], which has been parodied a number of times [7]. As Melanie parks her Aston Martin in front of the building, we hear the children singing “Risseldy Rosseldy,” an American version of the Scottish folk song “Wee Cooper O’Fife.” Hunter’s screenplay specifies this, and even includes every line of the song:

I married my wife

In the month of June,

Risseldy, rosseldy,

Mow, mow, mow,

I carried her off

In a silver spoon,

Risseldy, Rosseldy,

Hey bambassity,

Nickety, nackety,

Retrical quality,

Willowby, wallowby,

Mow, mow, mow.

She combed her hair

But once a year,

Risseldy, rosseldy,

Mow, mow, mow,

With every rake

She shed a tear,

Risseldy, Rosseldy,

Hey bambassity,

Nickety, nackety,

Retrical quality,

Willowby, wallowby,

Mow, mow, mow. . . .

And on and on and on. The song is about sixty percent nonsense words, but it is clear that its subject is a woman who is spoiled and thoroughly undomestic. In other words, she has no idea how to be a woman, in the traditional sense. The story is told from the perspective of her husband. When they were married, he “carried her off in a silver spoon,” indicating that she is treated with exceptional consideration, probably because that is what she is accustomed to. (“Back in your gilded cage, Melanie Daniels,” says Mitch in the film’s first scene, as he replaces a loose canary in its cage.)

Intolerably lazy, “she combed her hair but once a year.” And she could certainly not be expected to work on her husband’s farm (remember that Mitch and his family are technically farmers): “With every rake she shed a tear,” and “she swept the floor but once a year,” given that she “swore her broom was much too dear.” Further, she was hopeless at whatever she attempted: “She churned her butter in dad’s old boot. And for a dasher used her foot. The butter came out a grizzly gray.” To make matters worse, “the cheese took legs and ran away.” (The complete lyrics to the song can be found here [8]).

The Birds prominently features dysfunctional, modern relationships between men and women, and parents and children. Things are topsy-turvy in the Mitch-Melanie relationship. He is the pursued, and she the pursuer. (Just as, before Melanie, Annie had pursued Mitch to Bodega Bay.) Mitch is a grown man, whose manner and appearance are quite masculine, yet he is caught in an infantile relationship with his mother. Mitch calls her “dear” and “darling,” terms of endearment we usually associate with married couples. Because of this relationship, Mitch is unable to make a real connection with another woman. Lydia is the anti-mother, who places her own needs above those of her son and sabotages his relationships. The father, needless to say, is absent — save for his portrait, which gazes out at the family from the living room wall. Cathy is a smart aleck who contradicts her mother, and seems, as I mentioned earlier, to be seeking something from Melanie that Lydia cannot provide. Melanie (as we will see a little later) calls her father “daddy.” Development has been arrested. Roles have been reversed, or betrayed.

Nature cannot be denied for long, however. Either what had been unnatural comes to align itself with nature, or nature finds some way to strike back. This is at least part of what the bird attacks signify in this film (though I shall argue later on that a deeper level of interpretation is possible). As others have pointed out, “the birds” can be understood as referring to the women in the film (“bird” is British slang for woman). It is, of course, chiefly women who maintain the closest tie to nature, since they feel the call of the natural, sub-rational “self” stronger than men do. In The Birds, we find an assortment of women who seem out of alignment with that natural self. But whenever this occurs it is never women themselves who are to blame, it is their men. It is through her relationship to a man that a woman truly finds this alignment. By contrast, men become men primarily through direct confrontation with nature, or other men. One of the results of Hunter and Hitchcock’s story is that these topsy-turvy relationships become realigned with what is natural. Mitch becomes a man, Melanie a woman, and Lydia a loving and accepting mother. But more about that later.

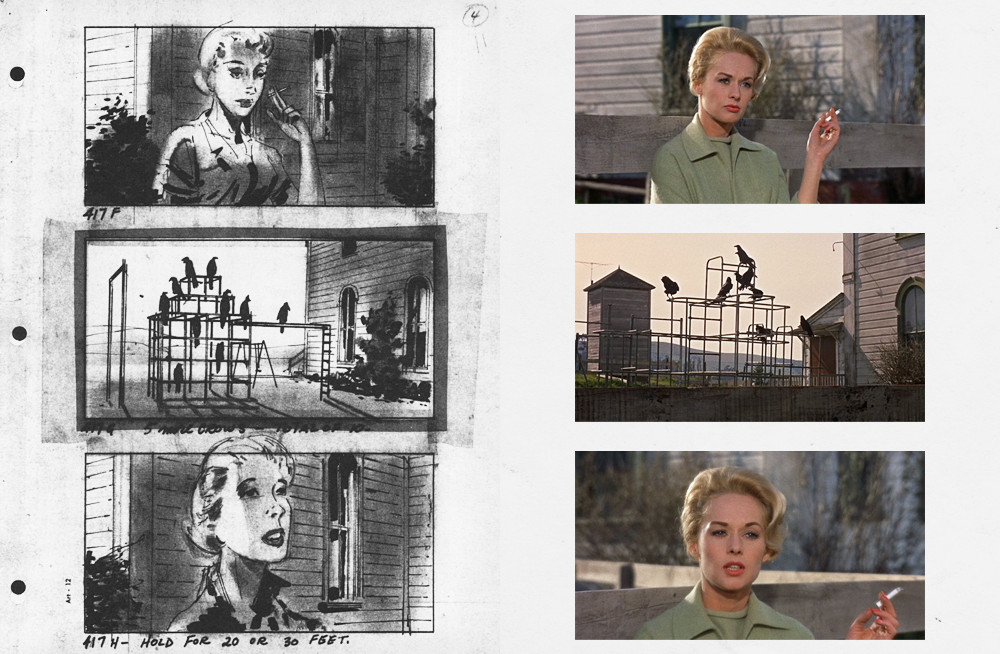

Melanie enters the building to find Annie leading the children in the song. She indicates wordlessly that she needs to speak with Annie, and the latter signals that they will be finished in a minute. Melanie exits and, trying to kill time, she sits down on a bench next to the fence surrounding the schoolyard. The children continue to sing. Directly behind Melanie, there is a jungle gym on the playground. Sometimes called “monkey bars,” this is an American invention which has been a fixture of parks and playgrounds in the US since the 1920s (though in today’s safety-obsessed culture, some have now been removed).

Melanie is clearly nervous and impatient for the children to finish their song. Behind her, we see a single crow land on the jungle gym. Melanie now takes a cigarette out of its pack and fishes in her handbag for a lighter. By the time she has found it and lighted the cigarette, three more crows have perched on the jungle gym. Then another — and another, and another. Hitchcock cuts back and forth between Melanie and the jungle gym. But then he focusses entirely on Melanie, showing her in close up smoking her cigarette, in a shot that lasts slightly less than twenty-eight seconds – but feels at least twice as long. This is audience manipulation at its most diabolical. We long to see whether more crows have gathered on the jungle gym, but Hitchcock refuses us this. It was his deliberate intention to hold the closeup of Hedren “until the audience can’t stand it anymore.”

The suspense is unbearable. Somehow, the children’s monotonous song only heightens it, and intensifies our horror (perhaps because of the contrast between the innocence of the children’s voices, and the malevolence of the gathering crows). Something in the air catches Melanie’s eye. Finally, Hitchcock cuts away from Melanie to show her point of view: a single crow flying high above. Electrified, she follows it as it comes to land on the jungle gym — joining what is now a huge flock of crows. A murder of crows, in fact.

Melanie rises from the bench, recoiling in horror from the sight of the birds (here, the closeup of Hedren is obviously a shot re-created in the studio, and not taken on location). In scenes such as this, by the way, some of the birds were stuffed props and others were mere cardboard cutouts. Real birds, twitching and fluttering, were placed strategically next to these, usually tied to whatever they were perching on. The power of suggestion causes the audience to assume that all of the birds are real.

Hurrying, but moving as silently as she can, Melanie enters the school — just as Annie is opening the side door leading onto the playground! Melanie pleads with her to close it, and points out the window and toward the jungle gym. “Look!” The schoolhouse is extremely vulnerable to attack, since, as Lydia mentioned, it has so many large windows. Annie and Melanie conclude that the only course of action is to get the children out of the building and down the road. Amid the youngsters’ rather comical protests, Annie tells them that they are going to leave the school as quietly as possible and head toward the town. When she gives the signal, they will begin to run. (It is somewhat sad to see these scenes of a well-dressed, well-behaved, and all-white class: a visual record of an America that no longer exists.)

At this point, a less imaginative director would show us the children tiptoeing out of the school. Hitchcock finds a brilliant alternative to this. He does not show us the children at all — not yet, anyway. Instead, his camera focusses on the crows massed on the jungle gym. For fifteen long seconds, he holds this shot. Then we hear the sound of the children’s feet. Annie has given the signal, and they are running. All at once, the crows take flight. They have been waiting for just this moment. This is the first time in the film that we seem to experience the action from the perspective of the birds.

We then see the children running down the hill, away from the school and toward town. What follows is one of the most technically complicated sequences in the entire film [9]. Footage was taken of the screaming children running away from the school, and running down the road toward the main part of town (actually, two completely different locations, in different towns). The children, along with Hedren and Pleshette, were then photographed on a soundstage running on a treadmill against a process shot. These shots feature the performers interacting sometimes with real birds, sometimes obvious fakes. However, the shots are intercut rapidly so that we cannot focus on anything for too long. This reduces the impression of fakery, and very successfully causes us to suspend disbelief and to become emotionally involved in the plight of the characters. At several points, certain children appear to be in real jeopardy. One little boy is pursued by a crow around a telephone pole. A little girl pitches forward onto the ground, the glasses flying from her face. Hitchcock shows us the thick, shattered eyeglasses in a closeup (another reference to “blindness”).

The majority of the birds shown in the sequence were the result of optical effects. Once all the footage had been shot, it was delivered to Disney Studios’ master technician Ub Iwerks, who used a “yellow screen” sodium vapor process to layer images of birds onto the footage. This process, superior to “blue screen,” was used very successfully by Disney in a number of films, notably Mary Poppins (1964). The result, predictably, looks a bit like a Disney cartoon in places. This is especially the case at the beginning of the sequence, when we see the birds fly over the schoolhouse and toward the children. It is obviously fake — but it is a good fake. In addition to Iwerks, Bill Abbott of 20th Century Fox worked on the visual effects for the crows. With two teams each working eleven hours a day, it still took six weeks to finish work on the scene.

Cathy comes to the aid of the little girl with the broken glasses (whose name in the screenplay is Michele). Together with Melanie, they seek refuge in an unlocked car. Melanie’s intention is to get the car going and get out of there, but the keys are missing. Crows descend on the car and, reduced to desperation, Melanie begins blowing the horn. But in a moment, the crows disperse and all is quiet once more.

The setting now changes to the interior of the Tides Restaurant, which, in the film’s revision of the real Bodega Bay, is just down the hill from the school. Melanie is standing at the bar talking on the phone to her father who, the reader will recall, is a wealthy newspaper owner in San Francisco. We will learn later that Cathy has been left in the care of Annie Hayworth. This is one of the most important scenes in the film, rich with indications of its larger “message.” It is also replete with good dialogue, interesting new characters, and tension. Here, Hitchcock employs “crosstalk,” a dramatic technique in which characters talk over each other, which is seldom seen in his films. It helps to create an atmosphere of mounting hysteria, in which things seem to be spinning rapidly out of control.

It is lunchtime, and the restaurant is busy. Watching over the proceedings is the Tides’s proprietor, the middle-aged Deke Carter. Flitting busily about the dining room is a dark-haired waitress, who is identified in the script (but not in the film) as Deke’s wife, Helen. A “drunk,” who is called Jason in the script (but not the film), sits at the bar sipping a beer. Just to make sure we know the man is drunk, the actor (Karl Swenson) speaks with an Irish accent. A gruff fisherman, Sebastian Sholes, sits at a booth hurriedly consuming his lunch. At another booth is a mother with two children, a boy, and a girl.

“Daddy, there were hundreds of them,” Melanie says into the phone. “No, I’m not hysterical, I’m trying to tell you this as calmly as I know how.” Just then, the door opens and in walks Mrs. Bundy. Though she appears only in this one scene, Mrs. Bundy is one of the most significant and memorable characters in the entire film. The script describes her as “sixtyish, wearing walking shoes and a tweed suit, a very masculine-looking woman with short clipped white hair.” Actress Ethel Griffies is perfectly cast in the role, and is dressed exactly as described. Griffies, born in Sheffield, England, had made her first stage appearance at the age of three, and at the time of her death in 1975, aged 97, was Britain’s oldest working actress. A spry 84 at the time The Birds was shot, she is considerably older than the Mrs. Bundy described by Hunter, but exceptionally sharp. The actress made a considerable impression upon the inexperienced Tippi Hedren.

Mrs. Bundy has arrived to purchase a pack of cigarettes from the restaurant’s machine. When she realizes that Melanie is speaking about birds, she begins to listen in on her conversation. “No, the birds didn’t attack until the children were outside the school. Crows, I think. I don’t know, Daddy. Is there a difference between crows and blackbirds?” At this point, Mrs. Bundy turns to her and, with great superiority, proclaims “There is very definitely a difference, Miss.” Griffies speaks with her own English accent. This, plus the drunken Irishman (from whom we will hear in a moment) plus the variety of American accents in the room, feels strange. (I have already mentioned in part one how the proprietor of the general store seems to speak with a Maine accent.) We get the impression that we are dealing not so much with the townsfolk of Bodega Bay as with a cross-section of humanity. As I will argue in the fourth and final part of this series, it is humanity itself that is addressed in this scene.

Mrs. Bundy is, as Hunter specifies, quite masculine, and this is accentuated when she begins brandishing a lit cigarette. We get the feeling that she might be the town lesbian. Ironically, she will now lecture us on nature, for Mrs. Bundy is an amateur ornithologist. She first displays her knowledge to Melanie by reeling off the Greek scientific names for the crow and blackbird species. Of course, this is the sort of superficial book learning that the ignorant mistake for knowledge: we do not know something just because we have given a name to it (a fallacy inherent in today’s plethora of medical “syndromes”). This is a perennial tendency of the human mind — not just to label things, but to imagine that this labeling somehow removes their otherness and brings them under our control. It is a tendency that begins in Genesis 2:19: “And out of the ground the Lord God formed every beast of the field, and every fowl of the air; and brought them unto Adam to see what he would call them: and whatsoever Adam called every living creature, that was the name thereof.”

Mrs. Bundy is, in fact, a droll parody of modern, Western, pig-headed scientism. When she hears from Melanie that crows attacked the school, she is immediately dismissive: “I hardly think either species would have the intelligence to launch a massed attack. Their brain pans aren’t large enough for such. . .” In other words, this proud empiricist knows a priori that what Melanie witnessed with her own eyes cannot have happened. Melanie responds, sensibly, “I just came from the school, madam. I don’t know about their brain pans but. . .”

Mrs. Bundy cuts her off: “Well, I do.” And she repeats this, emphatically: “I do know. Ornithology happens to be my avocation.” Then she adopts a tone of warm condescension: “Birds are not aggressive creatures, Miss. They bring beauty into the world. It is mankind, rather, who. . .” She had been about to deliver an eloquent speech against man, on behalf of the birds. But the voice of mundane, common life intervenes: “Three Southern fried chicken, Sam! Baked potato on all of them!” It is the voice of the waitress calling to the cook. Mrs. Bundy shoots her an aggrieved look, then completes her thought: “who insists on making it difficult for life to survive on this planet. If it weren’t for birds. . .”

How typical of Mrs. Bundy’s type — to side with the birds over her own species. How very white of her. This time it is Deke who cuts her off. “Mrs. Bundy, you don’t seem to understand. This young lady says there was an attack on the school.” “Impossible!” cries Mrs. Bundy. Mere facts are insufficient to derail this old crone’s relentless pursuit of the truth. (As Joe Biden recently proclaimed, “we choose truth over facts [10].”) The drunk at the end of the bar now cries “It’s the end of the world!” Then he quotes scripture, before taking another swig of his beer. “Thus saith the Lord God to the mountains, and to the hills, to the rivers and to the valleys, behold, I, even I, will bring a sword upon you, and I will destroy your high places. In all your dwelling places, the cities shall be laid waste, and the high places shall be laid waste! Ezekiel, Chapter Six.”

The man is drinking while Irish, so the audience is disposed not to take what he says seriously. Plus, he is quoting scripture, which for many modern people is a sign of ignorance and superstition. And yet, on another level, we are bothered by what this man says. Everything has been turned upside down in The Birds. Nature, it seems, has turned on man — and why this is happening is so far unexplained (in fact, it will remain unexplained). The old and familiar is now unfamiliar and terrifying. Lives are on hold. The ways in which we are accustomed to understanding the world around us are being challenged. Perhaps nothing will ever be the same again. Perhaps it really is the end of the world, and this drunken Irishman is a prophet. In such times, people are tormented by the nagging thought that perhaps the old books and the old ways were right, and that maybe we are being punished for straying from them. As Jef Costello has written recently [11] of the Coronavirus crisis:

There is something rather biblical about the whole thing, isn’t there? Throughout history, people have interpreted plagues as divine punishment. Almost always, they have been seen as brought on by moral or religious failings of the culture. We may laugh at the preachers and religious fanatics who think that Corona is punishment for gay marriage, but it’s actually good that people think this. And I don’t believe you have to be particularly religious to have such feelings; there is something deeply hard-wired about this response. “What have we done? Why is this happening to us?” It’s not a rational response, but then again 99% of human responses aren’t rational.

. . .There is, of course, no real connection between Corona and gay marriage or the transgender madness or the possibility that a man with dementia might be elected President of the United States. But it sure as hell feels like the chickens have come home to roost and God has decided to zap us, like he did with Sodom and Gomorrah and Egypt. I would thus diagnose the intensity of the current panic as a direct result of the average American’s gnawing sense that the culture has gone off the rails and deserves to be wiped out by a plague. All those fat people fighting over toilet paper in Walmart are just so many guilty consciences, cowering on their commodes before an angry God.

You can buy Jef Costello’s Heidegger in Chicago here [12]

The drunken Irishman’s rant is one element in a brilliant scene cleverly crafted to create an atmosphere of hysteria and impending doom. Mrs. Bundy, who is amused by the drunk, tries to reassure us: “I hardly think a few birds are going to bring about the end of the world.” But Melanie, frustrated by the old lady’s unwillingness to listen, counters, “These weren’t a few birds.” The woman with the two children has been silent this whole time, but it is evident that she is becoming increasingly alarmed by these stories. She whispers to the waitress, “Could you ask them to lower their voices, please? They’re frightening the children.” Of course, as we shall see, she is the one who is being most strongly affected by the conversation. The inclusion of this woman (who has some significant lines a little later) is another brilliant device to create tension. The presence of a person who is becoming increasingly nervous tends to make us nervous as well, like one tuning fork vibrating another. We begin to wonder whether we ought to be nervous also, and what this nervous person before us might do.

At this point, Mr. Sholes, the fisherman, tells the group about an incident from the previous week in which one of his boats was attacked by gulls. “Practically tore the skipper’s arm off,” he says. Deke mentions that Melanie was attacked by a gull two days earlier. Once again, Mrs. Bundy rides to the rescue. “The gulls were after your fish, Mr. Sholes,” she says. “Really, let’s be logical about this.” But Melanie counters with the perfect response, “What were the crows after at the school?”

“What do you think they were after?” Mrs. Bundy asks. Hitchcock’s camera now shows us closer shots of both characters, suggesting that this conversation is about to get intense. Melanie thinks for a moment, then says, “I think they were after the children.” “For what purpose?” Mrs. Bundy asks. With some hesitation, Melanie answers, “To kill them.” She does not want to say this because she does not want to think it, but this is her honest view, and she is correct. Now there is an even tighter closeup of Mrs. Bundy as she simply says “Why?” Her tone is challenging, but there is something in her eyes that suggests apprehension. For some reason, this moment is chilling. “I don’t know why,” Melanie responds, and Mrs. Bundy is instantly relieved, and now more arrogant and dismissive than ever. “I thought not,” she says, with evident satisfaction.

You see, according to Mrs. Bundy’s “logic,” if Melanie can’t explain the attack on the children, then it must not have happened. It is actually Melanie who is more logical than Mrs. Bundy, for she seeks the truth wherever it may lead, whereas Mrs. Bundy refuses to consider evidence. Why? Because it would overturn everything that she believes, and shake her conviction that logic has revealed the world to her and brought it under her control. To paraphrase what D.H. Lawrence says of Walt Whitman [13], Mrs. Bundy drives an automobile with a very fierce headlight, along the track of a fixed idea, through the darkness of this world. And she sees everything that way. Just as a motorist does in the night. “Birds have been on this planet since archaeopteryx,” proclaims Mrs. Bundy. “A hundred and twenty million years ago! Doesn’t it seem odd that they’d wait all that time to start a. . . a war against humanity?” Mrs. Bundy’s worldview has no room for the anomalous, for the unpredicted, and certainly not for the inexplicable. The darkness unilluminated by her headlight is vast, but she can’t see it, so for her it doesn’t exist.

To be continued. . .

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [14] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.