North West Frontier & the Oh-So-Modern Dilemmas of the Edwardians

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,287 words

I’d like to remind or inform my readers of a delightful, forgotten, and yet wholly wholesome and wise movie that was released in England in 1959. Its name: North West Frontier. The movie’s setting is the North West Frontier province in British India in 1905. The film’s McGuffin is a six-year-old heir to a local Hindu Maharaja. The boy is given over for protection to a British Officer named Captain Scott (Kenneth More) because Islamic insurgents are on the warpath and wish to kill the lad — from start to finish, this movie is something of a Western.

The boy is taken to the British consulate at the fortified garrison town of Haserabad with his American governess, Catherine Wyatt (Lauren Bacall). The Islamists attack the garrison fortress of Haserabad and overrun part of the railyard. Fearing that the rest of the fortress will fall, the consular officer Sir John Windham (Ian Hunter) orders Captain Scott to take the boy and his governess to Kalapur. (Personally, I thought the right thing to do was for all to say in the fort, contact the British Army by telegram for help, and wait for the cavalry to arrive, but then the movie would have been boring.)

Meanwhile, the first refugee train of Hindus has escaped Haserabad, and the other characters are introduced, including Lady Windham (Ursula Jeans), Mr. Bridie (Wilfrid Hyde-Whyte), the arms dealer Mr. Peters (Eugene Deckers), and reporter Peter van Leyden (Herbert Lom). Captain Scott discovers that there is an old train engine, called Victoria, in the railyard that has been lovingly tended to by its driver Gupta (I.S. Johar). Gupta and Captain Scott work up a plan to escape the besieged compound by train with the boy along with the other main characters, and two Sepoys, with one Maxim gun and a number of Lee-Enfield rifles.

The movie is tightly paced and the foreshadowing is on time and on target. The train winds its way across the arid and strikingly beautiful landscape that is the North West Frontier Province of British India. [1] [1] The Islamic rebels have blown up the tracks in two key places, leading to some very tense drama when Captain Scott and Gupta try and get the train and passengers through.

The Islamists also caught up with and slaughtered all but one baby in the aforementioned refugee train. When the characters come upon the slaughter, Mrs. Wyatt rescues the babe and names her Young India. As the film continues, the characters are fully developed, and we discover Peter van Leyden is a half-Dutch, half-Indian Muslim who sympathizes with the rebels. He ends up trying to kill the boy with the Maxim gun and is shot by Mrs. Wyatt with a Lee-Enfield rifle on the roof of the train while fighting with Captain Scott.

Needless to say, the train safely arrives in Kalapur. While it was highly possible that the movie could have become that of racist stereotypes, that doesn’t occur except in one instance where Captain Scott dresses down an imperious, but lower-ranking, British soldier. The “racist tropes” — such as they are in this movie — only involves stiff-upper-lip British Imperialists acting like jerks. All the Indian characters are played with a deadly seriousness.

The scenes in North West Frontier that show the slaughter of Hindus match what actually happened across India when it was partitioned between Hindu India and Muslim Pakistan. “Young India” started with appalling violence.

Something of a Western, but not a Comfort Western

In the late 1950s, Westerns were a popular money-making genre and this film mostly fits into the pattern of the Western, but it’s not what some film historians call a Comfort Western. A Comfort Western is a basic, good guy/bad guy story with a romantic tie-in somewhere. John Wayne’s [2] [2] The Comancheros [3] (1961) is one such Comfort Western.

North West Frontier is far more serious. Everything about this movie is a racially aware warning to whites (and Hindus). It is so truthful that it is surprising that such a film could have been made at all. When the film was released during the late 1950s, the “civil rights” movement was very powerful and white resistance was mostly disorganized and localized in the US South.

While the movie has some similarities to the John Ford classic Stagecoach [4] (1939), it is more powerful because it accurately reflects a racial/religious conflict that is ongoing, and the issues from it continue to drive the government policies of many nations. American and British troops are positioned near the North West Frontier Province today, and American and British drones fly over the area and bomb targets on occasion.

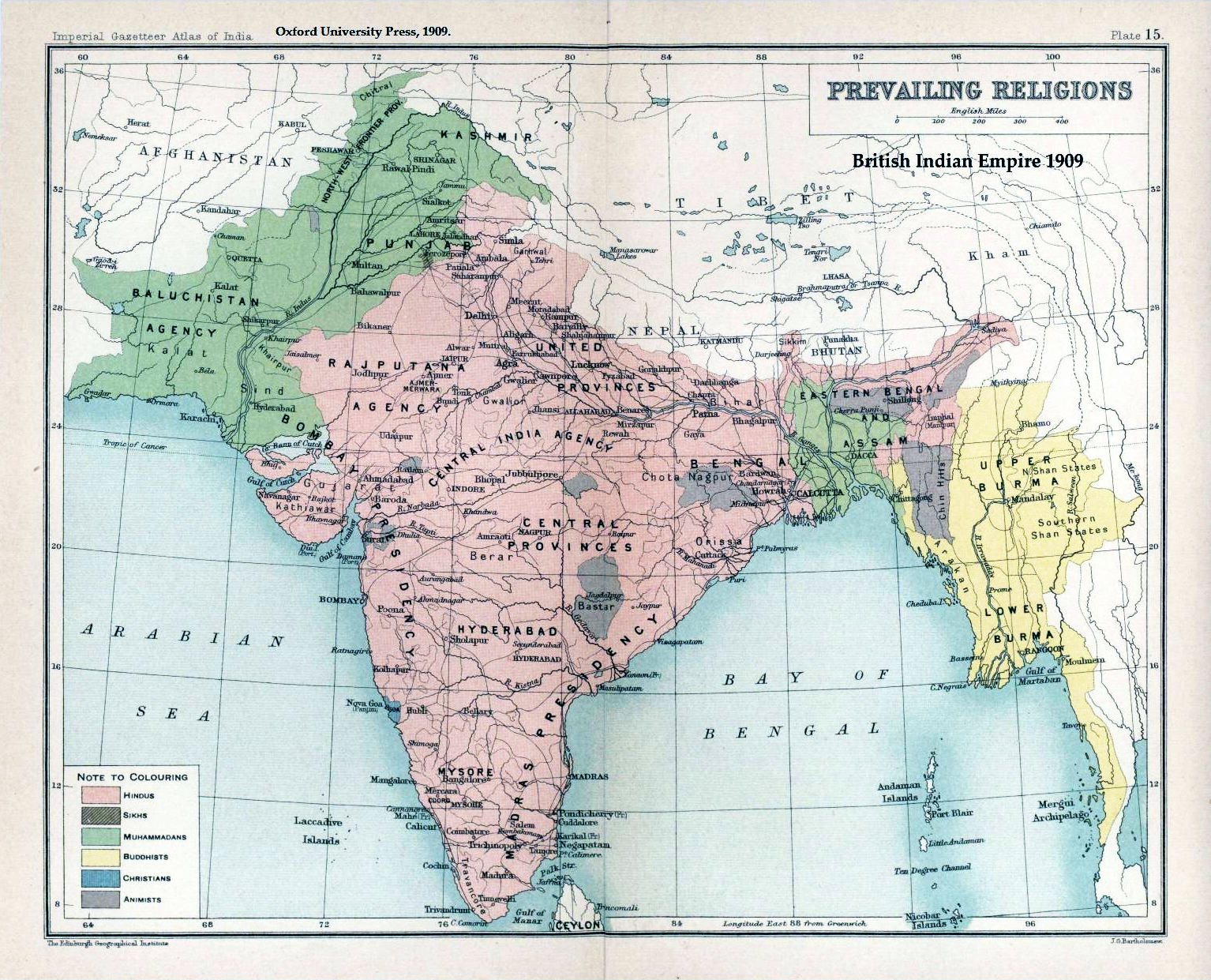

The root of the problem is one of vibrant diversity, resurgent Islam, and the end of the British Empire. India was never a united polity until the British made it so, but even under British rule, India was internally unstable. Throughout the British Raj, the British government had to deal with the problems of “vibrant diversity” in India. The Indian subcontinent is a land that is both linguistically diverse, racially diverse, and religiously diverse.

Race is hard to truly quantify in India, but it is certain that India comprises several different races. Many of the Indians in the northern parts of India are descended from the Aryan conquerors.

R1a: Modern DNA testing shows the Aryan invasion of India and its mostly racial categories identified by nineteenth-century scientists. The Indo-European people share a common ancestor, not only genetically, but in language, culture, and mythology, as well. [3] [5]

While India comprises several different races, the British Raj India’s main difficulty was between Hindus and Muslims. In 1947, British India split into India and Pakistan. Appalling sectarian bloodshed followed.

This movie is also a prophetic moral lesson for an audience of moviegoers living through the tense days at the height of the Cold War. By setting the time of the plot in 1905, Edwardian manners, politics, and styles are close to those living in 1959, but far away too. This is really important; had the plot taken place at any point during the nineteenth century, the events would have had a very distant, historical ring, like the War of the Roses, but by putting the events in the early twentieth century, the moviemakers are giving a message that can be paraphrased thusly: “When the dust settles from World War I, and the ongoing Cold War is that dust, older problems will return.”

You can buy Greg Johnson’s The White Nationalist Manifesto here [6]

Islamic aggression is one of those problems that resurfaced after the end of the Cold War. There is another moral lesson too. The Edwardian Era is viewed by those who came after it with rose-tinted glasses. Disneyworld in Florida, for example, has a nostalgic Edwardian theme, as does the movie Mary Poppins (1964). However, the Edwardians were not so different from ourselves. They lived in a time of ferocious political trouble, and victories were not coming as easy as before.

The Victorian-era Anglos swept away slavery, and made northern England — once poor — a wealthy industrial area. They also conquered two continents, expanded their Empire across the globe, and carried out many scientific and medical breakthroughs. In 1905, the Edwardians were holding on to an Empire recently rocked to its foundations by Dutch farmers in the Transvaal during the Boer War. Meanwhile, Europe, and indeed the rest of the world, rumbled with unrest that lead to World War I. Australian historian Christopher Clark wrote in his 2012 book, The Sleepwalkers, analyzing the origins of World War I that

it was easy to imagine the disaster of Europe’s “last summer” as an Edwardian costume drama. The effete rituals and gaudy uniforms, the “ornamentalism” of a world still largely organized around hereditary monarchy had a distancing effect on [Cold War Era] recollection. They seemed to signal that the protagonists were people from another, vanished world. The presumption stealthily asserted itself that if the actors’ hats had gaudy green ostrich feathers on them, then their thoughts and motivations probably did too. And yet what must strike any twenty-first-century reader who follows the course of the summer crisis of 1914 is its raw modernity. It began with a squad of suicide bombers and a cavalcade of automobiles. Behind the outrage at Sarajevo was an avowedly terrorist organization with a cult of sacrifice, death, and revenge; but this organization was extra-territorial, without a clear geographical or political location; it was scattered in cells across political borders, it was unaccountable, its links to any sovereign government were oblique, hidden, and certainly very difficult to discern from outside the organization. Indeed, one could even say that July 1914 is less remote from us — less illegible — now than it was in the 1980s. Since the end of the Cold War, a system of global bipolar stability has made way for a more complex and unpredictable array of forces, including declining empires and rising powers – a state of affairs that invites comparison with the Europe of 1914. [4] [7]

Although the fashions of the Edwardians are remote from our own time, the dilemmas they faced are remarkably similar. The most persistent problem is that of Islamic violence.

Important Symbolism

North West Frontier also has some rather obvious, but important symbolism that should be discussed. Mrs. Wyatt is a strong female character, but she is not a feminist. She carries out her feminine role very well in taking care of the boy and finding the baby Young India. She also defends her race when she shoots Mr. van Leyden.

The other Anglo characters reflect the wide range of the Anglo world with Captain Scott representing bravery and duty. Gupta’s character represents the Hindu nationalist political elite of the era. They are competent in technological matters, but they are unable to come to an accommodation with the Islamic portions of British India. The massacres that took place during the partition of India were a predictable outcome, and the British and (Hindu) Indian political elite were frustrated and ashamed that such a disaster occurred.

The reporter Peter van Leyden is a serious and excellent villain who exemplifies modern problems. Like so many mass shooters, Van Leyden is mixed-raced and alienated from both the worlds of Europe and the Indian subcontinent. He is a reporter who is biased. His work is fake news, but influential. Like the many people of Islamic origins in Europe today, van Leyden reckons with his alienation by embracing a globalist, violent form of Islamic Jihad. Take this scene, where van Leyden holds a Maxim gun on his fellow passengers:

Van Leyden: “I’m just one of the half-breeds you despise.”

Mrs. Wyatt: “What does killing us prove? That you’re not a half-breed?”

Van Leyden: “It proves that I am a true Muslim. That I care enough to fight and maybe even to die for my faith. For a country that will be all Muslim and I will belong there. Are you capable of understanding that?”

Mr. Peters: “You’re a criminal. You belong in jail.”

Van Leyden: “I find the moral indignation of an armament peddler rather touching.”

The interaction between Mr. van Leyden and Mr. Peters deserves further reflection. All Empires have a dark edge; they must walk a fine line between being legitimate and being feared. The British really did provide law and order to India, all while British merchants sold arms to savage tribesmen and opium to China. Independent Islamic nations also have a right, in an abstract sense, to a homeland, but there is a drawback to independent Islamic lands. As V. S. Naipaul said of Pakistan [8], “Step by step, out of its Islamic striving, Pakistan had undone the rule of law it had inherited from the British, and replaced it with nothing.” [5] [9]

The last, and most important, piece of symbolism is the train engine Victoria. Obviously, it represents the values of the Victorians which were starting to break apart by 1905 and nearly totally vanished by the film’s 1959 release, but these values deserve some praise. Today, Anglo society has made Venery a god alongside Moloch and Mammon, but sexual restraint, or at least striving towards the ideal of sexual restraint, leads to more children, more personal happiness, and a more stable society. Personal betterment and temperance are likewise important. There is something to say about dressing well and carrying on seriously. Victorian values may be clunking along like an old train engine, but they can still take you somewhere.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [10] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.

Notes

[1] [11] The movie is shot in Pinewood Studios, England, Spain, and Rajasthan.

[2] [12] See my article on Wayne here [13].

[3] [14] The British researcher William Jones wrote:

The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists; there is a similar reason, though not quite so forcible, for supposing that both the Gothic and the Celtic, though blended with a very different idiom, had the same origin with the Sanskrit; and the old Persian might be added to the same family.

[4] [15] Clark, Christopher, The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914, Harpers Collins Publishers, USA, 2012, Kindle Location 325 to 338.

[5] [16] Naipaul, V. S., Among the Believers: An Islamic Journey, Random House, Inc., New York, 1981, Page 168