In Search of Céline

Posted By Fenek Solère On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,704 words

Claude Sarraute: “And what, in your opinion, is the tragic element of our epoch?”

Céline: “Stalingrad. There’s the catharsis for you. The fall of Stalingrad was the end of Europe. There’s a cataclysm. The epicenter was Stalingrad. After that you can say white civilization was finished, really washed up.”

— Interview in The Paris Review, June 1, 1960

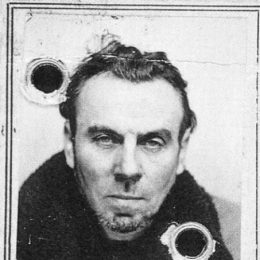

I first became aware of Louis-Ferdinand Céline when an artistic student friend scratched his portrait in charcoal on the cubicle door of the communal toilets in our halls of residence. Céline’s bird-like visage with glistening anthracite eyes stared intensely — almost accusingly — at me while I was urinating for the remainder of the year. Céline has a cynical face, underscored with a sword-swirling signature, that has intrigued me ever since I first beheld it. I first bought and avidly devoured a hardback edition of D’un Chateau L’Autre, or Castle to Castle (1957) in Quinto’s secondhand bookshop on Charing Cross Road. This was shortly before I was seconded by my first employers to Paris upon graduation.

There, while contemplating the career of the Vichy-supporting writer who witnessed the dying days of the Reich from the vantage point of the picture-postcard castle of Sigmaringen, I was lucky enough to live on an expense account in a rented studio apartment in the 5th Arrondissement close to the Pantheon where Voltaire, Rousseau, Hugo, and Zola are all buried. I would venture out in the early evenings after work under the famous edifice’s imposing neoclassical dome in search of Paris Noir. A line from Journey to the End of the Night (1932) often stuck in my mind:

An unfamiliar city is a fine thing. That’s the time and place when you can suppose that all the people you meet are nice. It’s dream time.

I was fascinated by the names of streets, metro stations, squares, and monuments. The Gare Saint-Lazare, Reaumur-Sebastopol, and the Rue du Chat Qui Peche sounded so much more romantic and mysterious than Trafalgar Square, St John’s Wood, or Southgate. I quickly found myself obsessed with the rich tapestry of memories that wrapped themselves like warm moleskin capes around Notre-Dame, Boulevard Saint-Michel, and the Dome des Invalides. Images of Villon, Rimbaud, the Commune, and the riots of 1968 filled my every waking moment.

Occasionally I would sit at a café table to partake in a handcrafted coffee and a crepe, forever listening, at least it seemed at the time, to endless renditions of Jacques Dutronc’s “Il est cinq heures Paris S’eveille” on RTL2. This ritual was made complete by watching perfectly-coiffed French hipsters flirt with girls in turtleneck sweaters sporting ponytails over tarte Tatin.

Something very deep inside me felt it was fate that had brought me to this point. A need to search for something within myself had taken the spectral form of a much-maligned collaborationist writer of whom the British critic, William Empson, had said “was a man ripe for fascism.” I was searching for Céline, who had only narrowly escaped the firing squads of the post-war epuration despite his works being lauded in publications like Action Francaise, Je suis partout, and Révolution Nationale.

This scribbler was denounced as a national disgrace in absentia in 1950 for expressing support for Jacques Doriot’s Legion of French Volunteers (LVF) and for stating that “we do not think enough about the protection of the white Aryan race. Now is the time to act, because tomorrow will be too late.” In 1951, Céline returned unrepentant from exile in Denmark after enduring a year’s imprisonment and a torturous trial to the city whose poor pre-war suburbs he once described as a continuum of “long, oozing house fronts” filled with “rickety dribbling children with nosefuls of fingers.”

I would spend hours aimlessly walking the streets of the ever-vibrant Montmartre, where Céline had practiced medicine as an obstetrician, watching out for the descendants of characters like his alter-ego Bardamu from Journey in the ristorante Coquelicot and practicing my schoolboy French while sipping Ricard 51 at zinc bars with hospitable locals.

You can buy Fenek Solère’s novel Rising here [1]

Overhearing chatter in the colloquial lingua franca, I could easily imagine those same vocal expressions echoing along the cobbled streets under the misty gauze of flickering gaslight in my ever-so-revered author’s own time:

When you stop to examine the way in which words are formed and uttered, our sentences are hard-put to survive the disaster of their slobbery origins. The mechanical effort of conversation is nastier and more complicated than defecation. The corolla of bloated flesh, the mouth which screws itself up to a whistle, which sucks in breath, contorts itself, discharges all manner of viscous sounds across a fetid barrier of decaying teeth — how revolting! Yet that is what we are adjured to sublimate into an ideal. It’s not easy. Since we are nothing but packages of fetid, half-rotted viscera, we shall always have trouble with sentiment. . . Feces, on the other hand, makes no attempt to endure or to grow. On this score we are far more unfortunate than shit; our frenzy to persist in our present state — that’s the unconscionable torture.

This still resonates with me many years later.

During my time in Paris, I had just worked my way through Céline’s other epic Mort a Credit or Death on the Installment Plan (1936), a sort of rhythmic rendering of Céline’s anti-heroic vision of everyday human suffering in the style of common street slang. I felt even more enamored by his sheer stylistic exuberance:

For me, you only had the right to die when you had a good tale to tell. To enter in, you tell your story and pass on. That’s what “Death on the Installment Plan” is, symbolically, the reward of life being death.

Credit so seduced me that I finally embarked upon reading the highly controversial Trifles For A Massacre (1937), a crumpled copy of which I kept under my pillow. Céline filled Massacre with references to “scientifico-Judeolatrous Dreyfusianism,” the “ass-reamings of Poo-Proust” and the “empty hype of the Jewish critics.” One particular paragraph captured my attention:

Sterile, conceited, destructive, swinish, and monstrously megalomaniacal, the Jews are currently accomplishing, to full capacity, and under the same standard as their conquest of the world, the degradation, the monstrous crushing, and the systematic and total annihilation of our most natural emotions as conveyed in all our essential, instinctive arts, in music, painting, poetry, theater. . . replacing Aryan emotion with the Nigger’s tom-tom.

Céline’s subsequent remarks about “the standard-bearers of high culture” foreshadowed the philosophy of Yockey as put forward in his monumental work Imperium (1948). Yockey’s analysis of the techniques used by the “culture-distorters” mirrored Céline’s own view that there was a deliberate strategy to “Freudianize” society.

These opinions are still used to besmirch his character and defame his art. All hell broke loose back in 2011, when the French Culture Minister, Frederic Mitterand, attempted to include Céline alongside Blaise Cendrars, Theophile Gautier, Franz Lizst, and Georges Pompidou in the 10,000 printed copies of the Recueil des Celebrations nationals. Immediate condemnation came from Serge Klarsfeld, celebrated Parisian Nazi-hunter and Holocaust memorialist, as well as the Association of Sons and Daughters of the Jews Deported from France. Klarsfeld insisted the Republic should not celebrate “the most anti-Semitic Frenchman of his day.”

This outrage was only partially countered by literary heavyweights who came to Céline’s defense. Men like Phillipe Sollers accused the Culture Ministry of “censorship”; Frederic Vitoux, a member of the prestigious Academie Francaise, compared the controversy to Stalinist “airbrushing” of history, and even the fanatically Zionist faux-intellectual Bernard-Henri Levy argued that commemorating Céline’s death would provide an opportunity to understand how a “truly great author” could be such an “absolute bastard.”

The whole affair made me think of Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, and Aldous Huxley — all of whom, at some point or other, shared similar (but probably less vitriolic) viewpoints with Céline.

These thoughts walked beside me like a silent omnipresent companion as I wandered up to the Saint Etienne du Mont, the shrine of Saint Genevieve, the patron saint of Paris, with its fine blend of Renaissance and Gothic architecture, and sat in its silent cool interior with my eyes fixed on the vast baroque pulpit. That day, it seemed Céline’s ghost encouraged me to scribble down the first draft of my debut novel The Partisan.

We should be ever-conscious that the same people Céline claimed governed the world “by the Golden Calf, by Mammon,” were the kith and kin of those who had celebrated the betrayal of Camus’s Algerie Francaise, provided the spokespeople for the “soixante-huitards” like Gerard Guegan, Daniel Cohn-Bendit, and Alain Geismar, sponsored the mass importation of Senegalese, Ghanaians, and others into migrant enclaves like Goutte D’Or in the 18th Arrondissement, and of course, welcomed the building of the Grande Mosque, projecting like some kind of flesh-eating ghoul over the lush grass lawns of the Botanical Gardens, the ominous shadow of its minaret and the call of the muezzin ringing out, not only across the City of Light, but over the red tile rooftops of provincial towns far and wide, proffering a frightening vision of France’s future.

Céline, the French James Joyce, would have none of it. His monumental novels were so filled with invective that they fizzled like the OAS plastiquage packages that were being detonated all over Paris in the early 1960s. The echo of the patriots’ explosives probably sounded like heavenly music to Céline’s sensitively-attuned ears during his final years in Meudon, a department of Hauts-de-Seine in the southwestern suburb of Paris with a substantial pied-noir population, and, ironically, the former political stronghold of one Nicolas Sarkozy.

Coincidentally, in May 1968, at the height of the Leftist mob’s rampage through Paris, the house of the intensely anti-Semitic writer of “filthy slang” and “brutal obscenities” was burned down and his remaining papers and manuscripts incinerated.

Now there’s a mystery if there ever was one.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [2] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday. Don’t forget to sign up [3] for the twice-monthly email Counter-Currents Newsletter for exclusive content, offers, and news.