Colonization for the 21st Century: Swades

Posted By Giles Corey On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled3,735 words

No man can serve two masters: for either he will hate the one, and love the other; or else he will hold to the one, and despise the other.

— Matthew 6:24

There must be an immediate and permanent cessation of all immigration into our nation, from this point forward. We do not need immigrants from anywhere, for any occupation, especially given that many have no occupation. Diversity is a weapon and our greatest weakness, not a strength. Ethnonationalism is good, natural, wholesome, and necessary; though our enemies screech that white nationalism, which is inherently and necessarily American nationalism, is “evil,” “perverted,” and “sick,” it is, in fact, the deracinated Egalitarian Regime [1] that is an alien disease, the true sickness unto death. National pride is healthy and fundamentally moral, and nationalism must be encouraged and celebrated in every nation; ethnonationalism is the purest and most altruistic love, and could not be any further from hatred, as the love of one’s own is not even close to being the equivalent of the hatred of others. As David Sims writes [2], “discrimination is a pattern of behavior by which we try to keep ourselves safe. . . You lock your door at night, not because you hate those who are outside, but because you love those who are inside.” We have our own nation to build. It occurs to me that the best approach to attempt to undo the catastrophic 1965 Hart-Celler Act is to encourage emigration from our nation and to discourage immigration into it. But how? I propose a two-pronged approach, perhaps better likened to a double-edged sword, one hard and one soft.

First, we must simply make the lives of immigrants as uncomfortable as possible. In other words, we must make it hard for them to live here. Though it would largely be symbolic, the American people — that is, the dwindling stock of real American people — would quickly get behind the establishment of English as our official language. We could use this as a springboard to eliminate bilingual government documents, automated phone menus and websites, and signage. Witness the governmental response to the Chinese coronavirus. Do we now doubt that it would be a relatively simple task to simply arrest and expel all illegal aliens within our borders? There are no “jobs that Americans won’t do.” There are only slave wages for which self-respecting Americans will not labor. Universal E-Verify would be easy to implement, complete with the criminal prosecution of noncompliant employers. The governors, mayors, and other officials of “sanctuary” jurisdictions should likewise be prosecuted, along with every single organization funding and organizing this Camp of the Saints invasion of our nation. We know who they are. Though I am essentially always a States’ Rights man, allowing a State to throw open its borders is the unilateral opening of the entire nation’s borders — this is what Angela Merkel’s Germany did to the European Union, effectively declaring itself a “sanctuary” country. “Birthright citizenship” is a farcical misconstruction of the Fourteenth Amendment, unconstitutional on its face. America is more than capable of securing its borders, from sea to shining sea. Most impactfully, though, we should impose an extremely large tax on remittances, perhaps as high as one hundred percent. And we must end the availability of all public services for illegal aliens. All of this, and our country would no longer appear to be so ripe for the picking.

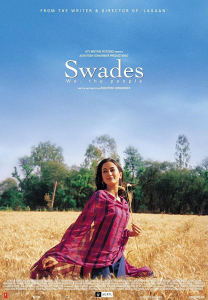

Second, we must inculcate in our immigrant population a sense of ethnonationalistic pride and foster their desire to build their own nations, rather than selfishly abandon those nations to their fate. It is imperative that we show immigrants that they must have pride for their ancestors, that the duty of every man is to justify himself to those betters who came before. In the antebellum South, and even during the early phases of the War, very few abolitionists actually advocated the full freedom and integration of blacks into white society; indeed, those who promulgated that view constituted a lunatic fringe. Most abolitionists supported “colonization,” best represented by the American Colonization Society, who argued for the return [3] of blacks to their African homelands. This is, indeed, how the nation of Liberia was founded. What I propose here as the second prong of our approach, then, is a sort of neo-colonization, by which we persuade immigrants that it is their moral duty to return to their homelands, where their talents are actually needed. One of the best illustrations of our strategy is depicted in the 2004 Indian film Swades, a moving, powerful testament to the ineradicable allure of Hearth and Home. Partially financed by the Indian government, if I recall correctly, Swades, which translates literally to “Our Country,” is a remarkably persuasive call for overseas, or “Non-Resident,” Indians to return home and arrest the “Brain Drain,” the phenomenon whereby the best and brightest minds of the Global South travel West for their education, never again to return. The title Swades is intentionally reminiscent of the Swadeshi movement, which originated as part of the nascent struggle for Indian independence and promoted domestic economic production over mercantilist British goods. I must also state at the outset that despite my devout Christianity, I deeply admire the Hindu nationalism that is finally ascendant in India. India is for the Indians, just as America is for the Americans.

You can buy Greg Johnson’s The White Nationalist Manifesto here [4]

Mohan Bhargava is an “Americanized” Indian, who serves as a senior project manager at NASA. He is quite successful, and any observer would remark that he is “living the American Dream.” He has been offered citizenship, yet he is downcast. We learn that this is the anniversary of his parents’ death, a car accident having killed them in his final year at the University of Pennsylvania. He has not seen his beloved nanny, Ms. Kaveri, who is “another mother” to him, since his parents’ funeral all of those long years ago; this was also the last time that he set foot in India. After that funeral, he corresponded by mail with Ms. Kaveri, but gradually became immersed in his work and “lost touch” with her; for months, Mohan now says, he has been thinking of her, worrying that she will get “old, feeble, and helpless.” He is consumed by guilt, guilt that he became “very selfish” and “stopped caring about her.” As will become clear, Ms. Kaveri functions as a sort of personification of Bharat Mata, or Mother India. As she is the “only thread” connecting his childhood memories, Mohan vows to go to India and bring her back to America with him, so that he can take care of her for the rest of her days.

On the plane, Mohan sees India once again, and wistful waves break across his face. Mohan’s arrival in the small, rural village where Ms. Kaveri lives is a major event; having visited a very similar Indian village on one of my two visits to India, I can attest to the fact that the arrival of a visitor, especially when said visitor comes from America, is heralded by the entire village. Ms. Kaveri and Mohan share a very emotional reunion, and Mohan becomes acquainted with the villagers, in the process rediscovering his Indian identity. The village is plagued by intermittent power outages that occur three to four times per week. One night, the village puts on a film screening, which is another rare and major event for which the whole village gathers. Just as the people begin to sing along to the classic Bollywood film, the power cuts out; to keep the children entertained, Mohan gets up and teaches them some of the constellations in the sky. Ms. Kaveri lives with a young teacher named Gita, with whom Mohan begins to fall in love; visiting her at the village school one morning, Mohan overhears another teacher deliver a lesson about Indian independence. Indians are still uniformly imbued with deep pride for 1947, despite the horrors of the Partition of India and Pakistan, which itself serves as a monument to the latent yearning for autonomous separation that all nations must necessarily feel. This stands in stark opposition to the dismal state of American civic and historical education. As Mohan reconnects to his roots, however, he remains an outsider; importantly, he sleeps in his luxury RV and drinks bottled water, which of course is an advisable practice for Westerners in any foreign country.

He criticizes India from the perspective of an outsider. In one conversation with Gita, he argues that Indian cultural traditions are “stopping our nation from going forward.” Note that he refers to India as our nation, meaning his. In the very next breath, however, evincing his identity crisis, he refers to “you Indians.” Gita replies, “Excuse me? Without culture and traditions, the country would be like a body without the soul.” Mohan continues:

We are plagued with problems. . . illiteracy is rampant. . . we have administrative problems. . . we are yet underdeveloped. . . your village doesn’t even have proper electricity. Caste discrimination, overpopulation, unemployment, corruption. . . our state of affairs is dismal. It’s pathetic. Pass me the salt.

Gita notes that Mohan criticizes without offering any practical solutions, to which Mohan states that his NASA job is for “mankind.” We must ask, however, which is the higher duty? That to one’s own people, or that to some amorphous and anonymous “global community”? One of the village elders admonishes him: “You’re just a visitor here. Roam around, enjoy the scenery. Why get involved in all this?” Mohan apologizes to Ms. Kaveri, an apology by proxy to the nation of India; he pleads, “I’m sorry that I didn’t take care of you. I’m sorry that I wasn’t there when you needed me most,” and asks her to come back to America with him. After she refuses, he continues, “Just come with me. You’ll feel very comfortable there. You can do everything very easily. It’s a much better life there.” Mohan is still acting purely out of self-interest here; he is focusing only on bringing her abroad with him, asking her to join his rootless sojourn.

Gita’s passion is education; this, she believes, is the key to improving her nation. Mohan works to enroll more of the local children in her school, and encounters resistance. He observes, with some horror, a child of no more than ten years betrothed; her father says that she is “not destined to be educated.” Gita is vehemently opposed to Mohan’s plan to bring Ms. Kaveri back with him, one night asking him: “Why did you have to come back? You have everything you need, right? We only have Ms. Kaveri.” Gita also admonishes him for telling her students that they should seek their education in America; she asks, “am I teaching these kids so they can go abroad and never come back, just like you? You NRI! Non-Returning Indian.” In one lesson, Gita emphasizes to her students that, “before gaining knowledge on foreign lands, it is important for one to know about one’s own country.” Later, one of Ms. Kaveri’s friends tells her, with reference to Mohan, to remember that “every piece of ice inevitably melts in its own water.” Taking her point, Ms. Kaveri sends Mohan on a long and circuitous route that requires him to traverse more of rural India. On his journey, Mohan witnesses the crushing poverty that still holds much of the country in a stranglehold. He meets a farmer in dire straits, who recounts his tragic story, telling Mohan that there is “not enough food to fill our stomachs, no clothes to wear, no roof over our heads, no education for children, no land. Only I know what I am going through.”

Mohan sees, firsthand, true destitution, drought, famine, malnourishment, and starvation. The land cries out to him, and he hears the call of Bharat Mata, Mother India. Ms. Kaveri’s scheme has succeeded in fully tapping into the latent reservoir of patriotism that she knew still remained inside of him. The symbol of his reawakening, his embrace of Indian identity, is his purchase of a cup of water from a beggar child — this is his first drink of Indian water that has not come from a sealed plastic bottle. Another subtle, yet key, scene occurs when Mohan puts on a dhoti, a traditional Indian men’s garment. He asks why he cannot simply wear his jeans, and Gita helps to tie the garment on him; this is symbolic of the communitarian and agrarian village ideal juxtaposed with Western individualism. I also could not help but notice that the traditional virtues of feminine chastity and the extended family are still alive and well in this village, which surely undergirds another portion of Mohan’s newfound love, for Gita, for the village, and for India itself.

At a town meeting, the village elders ask Mohan about the United States. When Mohan boasts of American infrastructure, which we must note is crumbling, one of the elders makes a quick rejoinder, asserting, “We have something that they do not, and will never have — culture and tradition. . . Ours is the greatest country in the world!” This is a beautiful sentiment that I hope every nation feels toward itself. Mohan responds, “I don’t believe that ours is the greatest country in the world. But I do believe that we have the potential and the strength to make it great.” The villagers are somewhat taken aback by his contention that India might not be the best country in the world. This exposes a common tension both within the developing world, formerly known as the Third World, and between that Global South and the advanced nations of Europe and North America: the conflict between the states of becoming and the states of being. Mohan notes that, contrary to the elders’ implicit claim that America has no culture, “America has progressed on its own. They have their own culture and their own traditions.” Growing irate, Mohan adds:

I’ve realized that we keep fighting amongst ourselves, when we should be fighting against illiteracy, the growing population, and corruption. Every day, in our streets and homes, every one of us keeps saying that this country has gone to the dogs. That this country is on the path to destruction. If we keep saying just this, we will actually end up being there one day. You need to do something to stop that from happening. . . everyone in the village. . . we are all to be blamed. Because the problem lies with us.

He walks away, after asking, “How long are you going to just live with your problems?”

We now arrive at the climax of the film. Mohan has answered his own challenge, deciding that he will finally act. He gathers one hundred men from the village, a crew that soon grows to include the entire village, men, women, and children, and builds a small hydroelectric power unit at a nearby mountain spring. His project works, thus supplying the village with a permanent and reliable source of electricity; in a magical moment, we see a bulb glow with light across the wrinkled face of an elderly woman — this is the first indoor electricity ever to grace the village. Imagine knowing the power of electricity for the first time, and we might begin to approximate the significance of Mohan’s gift. Mohan, we see, realized that it is his responsibility, his duty, to apply his talents, learned in America and applied with technology that Westerners invented, where they are needed. The villagers throw a wild celebration. The eldest man in the village, who it seems clung to life until he could witness Mohan bring his Promethean fire, holds Mohan’s hand as he dies, whispering, “now that you are here, I can die in peace.” With tears in his eyes, we may imagine what Mohan must be thinking: There is so much good left to be done here. They need me. India needs me.

You can buy Greg Hood’s Waking Up From the American Dream here. [5]

Mohan has long overextended the vacation that his employers at NASA had granted him; the satellite launch that he is managing is fast approaching, and they need him back to finish what he started. He knows that he must return to America. Gita tells him that “what surprises me is how you can think of going back after all that you have seen and learned here.” Mohan replies that, indeed, “I have gained a lot. I know that there are problems here, but I cannot live here.” Gita stands firm, asserting, “and I cannot live elsewhere. I want to marry you, but I won’t go to America.” Likewise, Ms. Kaveri turns down his invitation to America, stating, “at this age, I wouldn’t be able to adopt the ways and customs of another place. . . I am happy here. . . Had you stayed here, our family would have been complete.” The entire village turns out to send him off. One elder speaks for them all when he says that they “had forgotten that you were a guest. A visitor must leave one day.” Throughout the film, one of Mohan’s closest friends there had desperately asked to return with him to America. Upon his departure, however, the man declines, remarking, “I’m fine here. . . When the vine crawling along your wall crosses onto another’s property, individual homes are lost. It’s like a lamp on your porch, giving light to a neighbor’s house.” Gita gives him a wooden box filled with herbs, grasses, and the like; she tells him that the box contains “our culture and traditions. Little flowers of our faith. Our fields. Greenery. Rivers. Our customs. All these will keep reminding you of us. And maybe. . . it will persuade you to return.” Tearfully, he drives away; Gita, now another personification of Bharat Mata, fades away in the rearview mirror.

Back in the United States, Mohan finishes his project, seeing the satellite through to its final launch. While Mohan completes his work, we see that he is deeply conflicted and overwhelmed with guilt; as his team examines a map, his eyes hone in on India. Mohan, we observe, has come to see the emptiness of his deracinated life; as he goes through the motions, the scenes of his American existence are intercut with his memories, indelibly etched images of India and her people. While this occurs, a lovely song plays, whose lyrics say it all:

This land of yours

Is your motherland

It calls out to you

This is a bond that can never be severed

The fragrance of its soil

How can you forget it?

No matter where you wander off to

You’ll eventually come back

In new paths

In every sigh

To your lost heart

Someone will say

This land of yours

Is your motherland

It calls out to you

This is a bond that can never be severed

Life is telling you

You have accomplished everything

What is there to hold on to now?

Happiness has been showered upon you

But you’re away from home

Come back now

To a place someone would consider you their own

And call out to you!

This country of yours

Is your motherland

It calls out to you

This is a bond that can never be severed

This moment

Conceals within it

A whole century

And a lifetime

Don’t you dare ask why the road

Forks into two diverging paths

You are the one who has to choose which path

You are the one to choose

Which direction you take

This land!

This land of yours

Is your motherland

It calls out to you

This is a bond that can never be severed.

This deluge of memories is indeed the call of Bharat Mata.

After his satellite is launched, Mohan reaches his decision. He tells his incredulous friend, another NASA scientist, that “I must go back. . . It’s not only about Gita and Ms. Kaveri.” This friend sarcastically replies: “Oh, I get it now. Just because you lit a bulb, you think you can bring about a revolution in the country.” Mohan sincerely and forcefully responds, “if you can’t understand after hearing all of this, then maybe it’s pointless explaining anything to you. You’ll have to go there and see things for yourself. Otherwise, you’ll never understand.” As he walks out of NASA for the last time, his supervisor asks, “Mohan, you do realize what you’re going to lose?” Mohan replies that he only knows “what I’m going to gain.” Disgusted, his supervisor declares that he “could have gone places.” He responds, “I am going places.” Sardonically, his supervisor says, “Alright, Mohan. Go light your bulb.” The next scene affirms that order has been restored to the world, that all is as it should be — Mohan is back where he knows he belongs, in Gita and Ms. Kaveri’s village, married to Gita. He has taken a massive pay cut in order to work as a scientist for ISRO, the Indian space agency. He has determined, correctly, that he has the absolute duty to use his intellectual gifts for the advancement of his nation, for his people; Mohan has rediscovered his Indian identity, and shed the mottled garb of globalism that obscured his vision for the twelve years that he chose to abandon his home and the memory of his forefathers. He has atoned for his betrayal, and returned to the place whose call can never fall silent: Home.

It is an obvious truth that immigrants, legal and illegal, not only destroy our nation by inundating its borders, but also ruin their own in the process, abandoning their homelands to rot in fetid stagnation while they seek a quick buck in foreign lands that they can never truly be a part of, if indeed they even wish to. Swades, then, provides us with excellent insight into what is perhaps our greatest task — to kindly and sincerely nudge our metastasizing immigrant population into recognizing that they only have one purpose in this life, the same purpose that all men must share, differing only in the land at which it is aimed.

Go light your bulb.

Note: Swades is currently streaming on Netflix.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [6] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.