Arne Nordheim’s Draumkvedet

Posted By Alex Graham On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,108 words

Arne Nordheim was the most celebrated Norwegian composer of the 20th century. He is known for both his avant-garde electronic works and his large-scale orchestral works and music dramas. Nordheim’s Draumkvedet (“The Dream Ballad”), a music drama based on the medieval Norse poem of the same name, fuses his modernist idiom with folk influences to great effect.

Born in the town of Larvik in 1931, Nordheim initially was trained as an organist. He switched his focus to composition while at the Norwegian Academy of Music. After graduating, he studied with Vagn Holmboe in Copenhagen; he later encountered musique concrète in Paris and electronic music in Bilthoven and Warsaw. He was also strongly influenced by Krzysztof Penderecki and other composers of the New Polish School, who sought to create new sonorities and timbral effects using traditional instruments. His most famous works are Canzona per orchestra, which was inspired by the canzone of Giovanni Gabrieli, and Epitaffio per orchestra e nastro magnetico, a piece scored for orchestra and magnetic tape that he wrote in memory of Norwegian flautist Alf Andersen. One of Nordheim’s greatest admirers was Frank Zappa; they met each other in 1973 and became close friends.

Nordheim’s Draumkvedet was written to commemorate the 1000th anniversary of the founding of the Norwegian city of Trondheim. The piece premiered at the 1994 Olympic Games in Lillehammer, Norway.

The original poem, which likely dates to the 1200s, is considered a national epic in Norway. The ballad as Norwegians know it today is a reconstruction compiled in the 19th century by folklorist Moltke Moe in the tradition of Norwegian romantic nationalism. It has inspired several other Norwegian composers, including David Monrad Johansen (who supported Vidkun Quisling and was a member of Nasjonal Samling), Sparre Olsen, Klaus Egge, Eivind Groven, and Harald Gundhus.

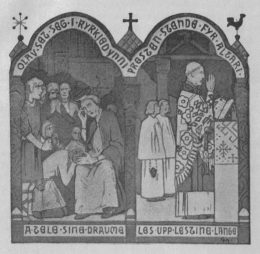

Draumkvedet blends Norse mythology with medieval Catholicism and resembles other visionary poems of the Middle Ages, such as The Vision of Tundale and The Dream of the Rood. The ballad describes the dream of a man by the name of Olav Åsteson, who falls asleep on Christmas Eve and does not wake up until the twelfth day of Christmas. Upon waking, he rides to church and regales the congregation with an account of his dream. In his dream, he crosses Gjallarbrú, the bridge spanning the river that separates the living from the dead in Norse mythology, and enters the Kingdom of the Dead. There he witnesses a battle between good and evil as well as the Day of Judgment.

Despite the ballad’s unabashed Christian triumphalism, it reads like a Norse epic poem and is rooted in ancient folk traditions. It is very similar to the “Lyke-Wake Dirge,” an English folk song about the soul’s journey to Purgatory that has a pagan, folkish character in spite of its Christian angle. (Interestingly, the term “lyke-wake” likely comes from Old Norse. To this day, the Yorkshire dialect contains many terms of Norse origin.)

You can buy Kerry Bolton’s Artists of the Right here [1].

Draumkvedet belongs to the tradition of kveding, or unaccompanied singing, which originated in the region of Telemark. Here [2] is an excellent rendition by Agnes Buen Garnås, a traditional folk singer from Telemark who is known for singing unaccompanied Norwegian ballads. Nordheim’s Draumkvedet pays homage to this tradition and is filled with recitative-like passages.

The ballad is an example of stev, a form of Norwegian folk song that consists of four-line stanzas. Most surviving gamlestev, the oldest type of stev, are from Setesdal and Upper Telemark. Individual stev were often sung as independent, monostrophic songs. This is reflected in Draumkvedet: each stev contains a distinct image. Nordheim’s setting preserves this quality.

Elements of Norwegian folk music can be heard throughout the piece. Like Eivind Groven, who hailed from the Vest-Telemark district of Norway, Nordheim uses harmonies found in Hardanger fiddle playing. The instruments used in Draumkvedet include the harp, Hardanger fiddle, and willow flute (a Nordic folk flute).

Draumkvedet is the only piece by Nordheim influenced by folk music. When he came on the scene in the 1960s, his music was controversial in Norway because he rejected the folk-inspired tradition epitomized by Grieg. He was at the vanguard of contemporary music — which is exactly what makes this piece so intriguing.

The explosive opening of the first movement, “Påkalling” (“Summoning”), has the air of an invocation. After a quiet but tense interlude, it concludes with a dramatic unaccompanied vocal passage (powerfully sung by Unni Løvlid) almost reminiscent of the imitation of natural sounds found in shamanic music. These vocalizations return in “I Pilegrims-Kyrkja” (“In the Pilgrim Church”), accompanied by the willow flute, and “Englemøte” (“Meeting the Angels”).

Nordheim frequently alternates between unaccompanied vocal passages and choral passages. “Framfor Kyrkjeporten” (“In Front of the Church Door”), for instance, contains lyrical vocal melodies intertwined with very Scandinavian-sounding hymn-like passages. Sometimes the vocal and choral parts overlap, as in “Straffene” (“The Sentences”).

Nordheim makes extensive use of bells and chimes of various timbres, which evoke the frostiness of northern landscapes. This is especially effective in “På Veg” (“On the Way”), “Englemøte,” and the ethereal “Draumar Mange” (“Dreams Many”), which concludes the work. “Draumar Mange” and “I Auroheimen” (“In the Other Home”) also contain drone-like sounds reminiscent of dungeon synth.

The most climactic moments of the piece are the martial choral passages in “Gjallarbrui,” which illustrate Åsteson’s perilous journey across the river of Gjöll (in the ballad, he encounters a serpent, a hound, and an ox); the cacophonous chanting in “I Pilegrims-Kyrkja” and “Grutte Gråskjegg” (“Grutte Greybeard,” a term for Odin), which represent the arrival of Odin and his hunt; and the conclusion of “Sjelenes Samlingsstad” (“Place of Congregation of Souls”), in which the chorus sings “Dies irae” against a background of increasing distortion and tension, representing the Day of Judgment and St. Michael’s weighing of souls.

The quality of this recording is excellent. The performers are uniformly good and handle the work with ease.

Overall, Draumkvedet is a highly compelling work that provides an original take on ancient material. Nordheim is skilled at creating otherworldly, oneiric soundscapes that have a timeless quality. He combines his modernist language with genuine respect for the folk traditions of his homeland in a way that rarely feels unnatural or contrived. Draumkvedet thus succeeds in looking to the future while also honoring the composer’s heritage — a worthy goal for ethnonationalist artists.

If you want to support our work, please send us a donation by going to our Entropy page [3] and selecting “send paid chat.” Entropy allows you to donate any amount from $3 and up. All comments will be read and discussed in the next episode of Counter-Currents Radio, which airs every Friday.