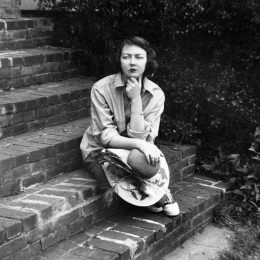

Remembering Flannery O’Connor:

March 25, 1925–August 4, 1964

Posted By

Margot Metroland

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

1,779 words

Like her near-contemporary Gore Vidal (both were born in 1925), the fiction writer Mary Flannery O’Connor had her first brush with fame via a Pathé movie newsreel [1]. She had a pet chicken whom she’d taught to walk backward. Gore’s fame came a few years later when he piloted an airplane [2], age ten.

O’Connor was born in Savannah, Georgia, where she lived until she was 15, whereupon her family moved to an old homestead in the former Georgia capital of Milledgeville, where she spent much of the remainder of her life. Her father had come down with lupus, the disease that would kill him in 1941 and Flannery in 1964. The O’Connor family was reasonably well-off. Her father had been a real estate broker, while her mother was the daughter of a wealthy, longtime Milledgeville mayor, and ran several farms in the Milledgeville area. A more distant relation was Admiral Raphael Semmes, renowned for captaining the famous commerce-raider CSS Alabama in 1862-64.

Other than dying young, O’Connor is usually noted for several aspects of her work. The most remarkable is her enduring legacy. There are few popular writers from the 1950s and early 60s who are still avidly read and re-read today, yet still taken seriously as literary artists. (To throw out a few names: James Gould Cozzens, Sloan Wilson, Hamilton Basso, Irwin Shaw. Have you read them lately? How seriously do you look at the one-novel wonders J.D. Salinger and Harper Lee?) Another is the perfectionism and narrow range of her craft; she’s remembered for about two dozen short stories and two novels, most of which are pointed to as perfect exemplars of a literary style that is commonly described as Southern Gothic.

More rarified, if less celebrated, is the influence of Southern Agrarianism. The Agrarians were a literary movement that arose in the 1920s in rousing contempt against the demeanment of the South in popular journalism. Two famous examples of this were H. L. Mencken’s description of the South as “The Sahara of the Bozart [3]” (i.e., Beaux-Arts), and the notorious Scopes Trial in Dayton, Tennessee in 1925. Allied with this is her Catholicism. Critics often point to it as integral to her work, but arguably it was not. This notion seems to come mainly out of O’Connor’s personal correspondence, and recollections by friends. After her first few stories, Catholicism per se seldom poked its way in. I’ll come back to this later.

* * *

What Flannery O’Connor wrote, mainly, could be described as black comedies in a Southern Gothic style, generally about country and small-town people in Georgia. But the actual sense of geography in her stories is diffuse: it’s a vast rural landscape that might be in Georgia, but could also be in Tennessee or Alabama or even Mississippi. In “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” an old woman thinks she recognizes an old Georgia plantation, but upon investigation suddenly decides the real place was in Tennessee.

I always find myself wondering whether this vague notion of place is truly a Southern thing, or just something Flannery O’Connor imposed on us. When I was little, I certainly knew when I was in South Carolina and then passed over the border into Georgia, or Alabama; much as I’d know it when we drove through Pennsylvania to New York State. What I’m saying here is that O’Connor gives us a generic, fanciful “South” that is not really truthful, but probably reflects the world that she knew. Perhaps, if you seldom stray far from Milledgeville, Georgia, it is possible to imagine the rest of the (Southron) world as a grander, expanded Milledgeville.

I’ll tell you a Mississippi story from forty-odd-years back. There was (and is) a famous color-snapshot artist named Bill Eggleston, and he was taking a big car trip from Memphis through the Delta section of Mississippi. Some relatives were along, including an elderly lady related to Bill’s wife Rosa. And everyone saw a roadside produce stand, attended by an old black man advertising himself with a big placard:

SAM DAVIS

Free Ice Water

Having a little fun, Bill and Rosa teased the Old Lady that this upcoming stand was owned by none other than Sammy Davis, Jr. The Old Lady, born circa 1885, took a close look at the sign. “Whah, the nerve o’ that nigguh! Tryin’ t’ give away free ice water!”

Now, the real-life story has no real point, other than someone cruelly teasing an 85-year-old during a road trip through the Delta. But when we heard this story fresh, circa 1978, it sounded like pure Flannery O’Connor. And that seems to be the overall effect on Southern culture since the 1950s. Anything eccentric, antiquated, or bizarre is seen through the literary prism of Flannery O’Connor.

You can go back twenty years before my story, back when To Kill a Mockingbird was being written, and you can easily get the idea that Harper Lee utterly ransacked the early stories of Flannery O’Connor to fill out that novel. There’s the recluse Boo Radley, of course, a rewrite of any number of divine madmen in O’Connor. The children Scout and Jem build a “morphodite” (hermaphrodite) snowman, which a neighbor finds diabolical (O’Connor had put a hermaphrodite sideshow freak into a story a few years before). Precocious and visionary children abound in O’Connor, so here in TKAM we get Dill, the towheaded little boy who is half Truman Capote (Harper Lee’s real-life friend) but otherwise just a reworking of characters from O’Connor and Capote himself. As I’ve written before [4], Harper Lee also padded out about a third of her novel with a lurid, meandering subplot of interracial rape, based mainly on the case of Willie McGee. That fatuous subplot does not come out of O’Connor, but it gives you the other bookend of popular perceptions of small-town Southerners: if they’re not madmen or mutants, they’re indefatigable racists.

* * *

What always gets my goat when I read potted analyses of Flannery O’Connor’s work is the undue emphasis put upon her Catholicism. Over and over again we read that her work is replete with “Catholic themes.” To me, this seems to be pushing on a string. While O’Connor did indeed admit her fiction had Catholic, or at least Christian, underpinnings, this is open to gross misinterpretation. Yes, there’s a lot of God-talk, and scriptural allusions find their way into her stories, but it’s usually not specifically Catholic, and when it’s there it’s only because those are things that the people she writes about really do talk about.

You can buy Greg Johnson’s The White Nationalist Manifesto here [5]

I would draw an analogy here to J.R.R. Tolkien, another Catholic writer whose work is continually sifted for religious allegory that isn’t there. Tolkien once averred that The Lord of the Rings is a “fundamentally religious and Catholic work [6],” but he was speaking as a philologist and literary scholar, not as an armchair theologian. LOTR derives largely from medieval Christian romances (The Song of Roland; Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, which Tolkien once translated) as well as pre-Christian Nordic literature that comes to us through Christian sources. Tolkien regarded LOTR as taking place in a pre-Christian world, so we shouldn’t waste time wondering whether self-sacrificing Frodo is a Christ-figure, or if Galadriel is an avatar of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Coming from Catholic and Southern antecedents myself, I always saw right through the pat critical characterization of her work as “Catholic” literature. The fact is, there isn’t much Catholicism in O’Connor’s stories and novels themselves. What I think was really going on here is that critics knew she was an important and influential writer, but had to notice that her stories are too often horrifying, right on par with Catholic martyrology (or, for that matter, the 20th-century goings-on in Moscow’s Lubyanka or Budapest’s House of Terror). In “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” a selfish old lady leads her family to death at the hands of psychotic killers, and at the end pleads for her own useless life to be saved. The atheist “preacher” in Wise Blood blinds himself with quicklime. In the novel The Violent Bear it Away, a 14-year-old boy is seduced by a man in a “lavender automobile” who plies him with reefer and whiskey, till he passes out; upon waking, he painfully discovers he’s been cornholed. In “The Life You Save May Be Your Own,” a slippery drifter agrees to marry a woman’s deaf-mute daughter in order to steal the woman’s car, then abandons the deaf-mute bride at a roadside diner.

I submit that a Flannery O’Connor type could just as easily have sprung from a devout and intellectual Presbyterian upbringing. The doom-laden imaginings and drive of the Dulles brothers and Henry R. Luce seem, to me, to bear a close parallel to the strict and Jansenist imagination of Flannery O’Connor. You might even have an O’Connor who was Anglican or possibly even Quaker, if she went to church or meeting, and took her faith seriously. But what you wouldn’t find is a talented O’Connor awash in the mushy here-and-now meanderings of a progressivist cleric or Reinhold Niebuhr. The difference here, for a literary artist, is between the habit of belief and the habit of doubt.

On another score, I find it an interesting fact that fiction writers who are lifelong Catholics (O’Connor and Tolkien and others) seldom inject Christian doctrine or liturgy into their writings. They just don’t write about Catholicism. No, they don’t. If you try to find exceptions to this, what you’ll probably come up with is a lot of converts: Graham Greene, Ernest Hemingway, Walker Percy and inevitably Evelyn Waugh, who ruined one of his better books (Brideshead Revisited) with soppy religiosity. Or G. K. Chesterton, who didn’t write his Father Brown stories and The Man Who Was Thursday because he was Catholic; rather, he became Catholic later on, after years of working things out in his fiction and controversialist essays. Or those Jewish lady scribes, Muriel Spark and Mary Gordon, who announced themselves as Catholic Novelists — and never shut up about it — in order to distance themselves from their Jewish side and (in Spark’s case at least) to attract some of the Evelyn Waugh mojo.

And then finally you have the backsliders: popular writers such as Hilary Mantel (Wolf Hall), or O’Connor’s fellow Georgian, Margaret Mitchell (Gone with the Wind), both of whom left the Church and were forever after obsessed with it. Hilary Mantel can’t stop telling us that Sir Thomas More was a scoundrel, and Henry VIII was right to break with the Papacy that pronounced him Defender of the Faith.

As for Margaret Mitchell, she gave us an Ellen O’Hara, Scarlett’s mother, who is always praying the rosary; something Margaret herself hadn’t done in decades.