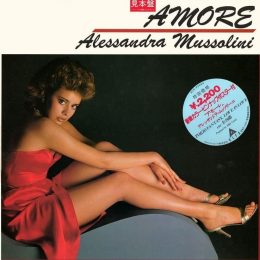

Valentine’s Day Special: Alessandra Mussolini’s Amore

Posted By Scott Weisswald On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,122 words

It’s February 14th, and love is in the air. What better way to soundtrack today’s romantic escapades than with Alessandra Mussolini — the granddaughter of Il Duce himself — and her sultry, Japanese-released city-pop record, Amore?

Released in 1982 exclusively for the Japanese market, Amore was rediscovered by vinyl-philes and YouTube-core fans looking for their fix after the invasion of vaporwave and other Japanese-influenced music on the Internet in the mid-2010s. (After all, you can only listen to so much Mariya Takeuchi before you need something new.) Amore is a delectable slice of retrofuturistic, funky pop fun that oozes sentimentality. As the icing on the musical cake, it was recorded by none other than Alessandra Mussolini — the same Mussolini who was a Member of European Parliament for Forza Italia until 2019.

Amore isn’t just a gimmicky collector’s item, though copies of it do usually sell for about 80 euros on Discogs [1]. It’s a true addition to the Italo-disco, future-funk, city-pop tradition that would influence future Japanese-European collaborations in genres such as Eurobeat or even “kawaii death metal.” There’s also, of course, humor to be found in Alessandra going to Japan, an ally of her home nation during that infamous conflict, to record this album. Amore is another example of the strange fellowship that Europeans have with our odd, kimono-wearing friends on the other side of the world.

Outside of being a historical curiosity, Amore lives up to its name by being chock-full of romance and just the right amount of optimistic 80s cheese. The opening track, “Tokyo Fantasy,” has a bouncy rhythm and energetic chorus — sung mostly in Japanese. The classic plucked bassline that defined Euro-influenced pop music in Japan never misses a beat, and Alessandra’s voice is filled with glee. “Tokyo Fantasy” makes for a great dancefloor call-to-action; it somehow transcends its cliches, making it far more endearing than it is dated while listening to it in the current year.

“Carta Vincente” is the second track, a heavily jazz-influenced song with rhythmic piano and textured notes of horn and string. “Vincente” is sung in Italian, and has a peculiarly invigorating lobby-music feel to it. Much of this album has a haunting, somewhat enchanted quality; one couldn’t replicate this record, no matter how hard they tried, because it is distinctly a product of its time, place, and creator. “Vincente” is a great example; it has Alessandra’s glamorous tendencies, reflected in dramatic chime slides; it has the funky, precise production hallmarks of a Japanese single; and it’s immediately recognizable as being from the early 80s.

The third track, “Amai Kiouku,” has the slickest aesthetic of any song on the album. Held together by a jangly guitar leitmotif, seasoned with piano, and made complete by Alessandra’s graceful crooning in Japanese and English, “Kiouku” is the perfect soundtrack to a night drive down the coast with your sweetheart. It’s even got a metallic guitar solo in the middle.

“Insieme Insieme” is a slower cut than the previous tracks, making it an excellent halfway point. Mostly consisting of graceful strings, a syncopated percussion section, and Alessandra’s remarkably-ranged vocals, “Insieme” moves between laidback and high-strung sections with ease. Italian, perhaps the most romantic of the Romantic languages, is what Alessandra sings in for “Insieme.”

Amore makes for an interesting case study in how linguistic perceptions can shape the mood and subject matter of a song; on her more cosmopolitan, upbeat cuts, Alessandra opts primarily for English. On groovy, future-focused tracks, she cuts tracks in surprisingly well-pronounced Japanese. And on luscious, orchestrally-oriented songs, she sings in Italian. Whether this was a deliberate stylistic choice or simply the direction that the songs in each language went remains something of a mystery. After all, all three languages had then, and have now, a unique degree of exoticism: English is the global lingua franca, Japanese the tongue of high-tech cities, and Italian the quintessential language of wooing.

“Love is Love,” the fifth song, is a mostly run-of-the-mill Italodisco beat. It does have some unique elements, like the bass breakdown that takes over the soundscape about halfway through, as well as some intriguing drum breaks that punctuate verses. Absent these peculiarities, “Love is Love” is mostly forgettable. They can’t all be zingers!

“E Stasera Mi Manchi” has a warbly, island-like bassline and melody. Alessandra’s singing on this track is more subdued in the verses, creating a sense of contrast when she pours her heart out into the chorus. “Manchi” has some of the most noticeable variations in tempo and tone of any track on Amore, making it a pleasant ride to sit through.

“Tears” is the second-to-last track, sung in English. It’s more melancholic than a lot of this album; Alessandra sings of a crying woman and the love that she has lost. Any good romance album requires a breakup ballad, and Alessandra satisfies with “Tears.” Unlike many other songs in the breakup genre, “Tears” is from the perspective of a woman consoling her friend who has experienced heartbreak. Alessandra, as the narrator, is an empath who feels her friend’s heartbreak as if it were her own. Musically, “Tears” doesn’t stray much from the normal formula downtempo city-pop follows.

“L’ultima Notte D’amore” is the final track. It’s got a powerful backing orchestra and choir, giving it the energy that a cumulative closing track needs to satisfyingly end an album. It’s a mid-tempo track with a pleasant soundscape. Alessandra’s Italian on “D’amore” is slightly affected, with extra emphasis placed on her rolls and open vowels that give the track some Meditteranean flair. “D’amore” also ends with a fade, which may have been the best possible way to say goodbye. While far from remarkable, the atmosphere of Amore is one that is easy to relax in, and hard to let go of.

Amore is one of those pieces of art that exists in defiance of known cultural laws. Mussolini’s family, as the global elite would have it, should have been completely blackballed and barred from public life. Instead, the family held on to both their name and their optimism. Amore is far from innovative. It’s not the most enthralling musical work recorded, either. Rather, Amore is special because it’s a reflection of our people’s adorable idiosyncrasies. Who else would want to go to Japan to sing love songs in Italian? Who else would want to mix violins and Linn drum machines? Alessandra Mussolini did it because she knows stuff like this makes us smile. Amore doesn’t seem to be about a specific romantic partner; it’s about the feeling of being in love in general, a literary tradition that our people established centuries ago, and keep alive today.

It’s a little love letter to our collective quirks, and the perfect album to dedicate this Valentine’s Day to our people.