The Red-Pilling of Spencer Quinn

Posted By Spencer J. Quinn On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,980 words

I’m one of those lonely people who red-pilled himself. It happened twice: Once in my early twenties and once in my early forties. And since a commenter on my previous article “The Tipping Point” [1] asked for me to explain how that happened, I thought I’d share.

I became aware of the critical nature of race — vis-à-vis blacks and whites — in my early twenties after a few years of living on my own post-college. I can trace it back to the day I started paying my own taxes. As a good, non-materialistic leftist, I made so little money back then, yet I had to pay what was, to me, a significant sum: something like $800. I didn’t have $800; in fact, I probably owed in college loans more than thirty times what I had in my checking account at the time. And, of course, I didn’t have any savings. So the very idea that I owed Uncle Sam that kind of scratch after barely cobbling together around $12,000 in a year was. . . insulting. I’m not against taxation per se, of course, but I knew something was fundamentally wrong with this. This event was the first in my life that made me question the major decisions I had made thus far.

[2]

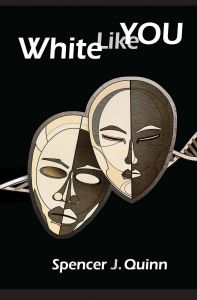

[2]You can buy Spencer Quinn’s novel White Like You here [3]

Back then, I was working in close quarters alongside people beyond the university milieu — black people, mostly. These were tedious, low-paying jobs. During college and shortly after, I, like any good liberal, had been immune to all arguments and evidence pointing to racial differences. I had heard the race-realist arguments before, especially from older family members, but felt they were mean and cynical. I had always been clever enough to refute them. (If you’re clever enough, you can “refute” almost anything.) Yet I noted how difficult it was to do this, especially against family members who did not share my university education. Despite my efforts, their arguments always seemed to hang together pretty well.

That always worried me.

After college, I began to study race from an egalitarian standpoint, wanting to understand why the races had markedly different outcomes in life. I was concerned mostly with black-white differences, but all races mattered to me. For some reason, I had always found this topic interesting. Despite vigorous research, I could only find one plausible explanation. It was presented in a little book called Chains and Images of Psychological Slavery by someone named Na’im Akbar. According to this Akbar, generations of physical slavery shackles the mind with a slave mentality, causing the descendants of slaves to inherit these shackles even if these descendants themselves are free. And with a shackled mind more often than not comes a life of crime, poverty, and low achievement.

This seemed to make sense. It certainly explained everything quite neatly. But its Lamarckian nature nagged at me. What exactly was the mechanism which caused black children to inherit psychological defects that their ancestors acquired during their lifetimes? I knew enough about basic genetics to know that that wasn’t how inheritance worked. Did black parents somehow train their children to fail? Did they inculcate these psychological chains into them? I found that highly unlikely.

Then, one day, I watched carefully as a black custodian at my place of work was telling some of us a story. The man was good-natured and quite animated, but not terribly bright or educated. His English, as is typical with most poorly-educated blacks, was atrocious. It was as if his mind could not parse the complexities of the language rapidly enough to express himself properly in real time. So, in order to prevent his mind from having to operate more quickly than it was accustomed to, he pidginized the language to make it easier to pronounce. Entertaining as his story was, listening to him was a particularly ugly experience.

And then it hit me. He is not this way due to his environment or due to what happened to his ancestors in the past. These external factors could not possibly have impacted his language parsing abilities. “White people simply do not have that much power,” I remember thinking. The reason must be purely biological. This must be the phenotypic expression of the genes that this man was allotted at conception. He is who he is, and there is no one to blame for it. All at once, the race-realist arguments of my family members flooded back into my mind. I realized that they had been right all along — and that I had wasted years of my intellectual development pursuing an egalitarian ideology that was patently false.

It was at that moment I became a conservative. And from there, there were few barriers between me and the Right.

My second act of red-pilling came as a result of reading Kevin MacDonald’s The Culture of Critique. I started the book prepared to be highly critical of it since, at the time, I was quite favorably disposed towards Jews. I had Jewish friends; I was aware of Jewish high-IQ and accomplishment; I had read Paul Johnson’s The History of the Jews; I was in solid agreement with Jewish writers such as Daniel Pipes and David Horowitz. Most importantly, perhaps, I was still nursing a grudge over 9/11 (and I still do, by the way). Conservative, nationalistic Jews and I shared an enemy — and this made me a committed ally.

After Mitt Romney lost in 2012, something inside of me died. Even though I knew he wasn’t as conservative as I was, I genuinely liked Romney back then and thought he would win. Sure, I was a race-realist, but I still believed somewhat in the melting-pot, proposition-nation notion behind a racially diverse America. When Romney lost, and lost badly, I took my first painful steps towards red-pilling myself about Jews — and this came, perhaps inevitably, as a result of my burgeoning white identity.

After the defeat in 2012, I learned first off that liberals do not care about the economy or making America strong. Despite having atrocious records on both accounts, Barack Obama was buoyed back into power by millions who loved him intensely. But why did they love him so? If it wasn’t for any objective reason, then it had to be for a subjective reason. Of course, I know now what the subjective reason is: Barack Obama wasn’t white. That’s why they loved him. The fact that he was good looking and could speak well was merely icing on the cake.

In November 2012, I realized that non-whites would gladly sacrifice America’s greatness and prosperity if it meant keeping one of their own in power. Once this idea crystalized, I understood the greater struggle in which America was currently engaging: whites versus non-whites. The very idea that these two groups could actually cooperate to pursue common goals suddenly became ridiculous to me. There could never be common goals in a racially-diverse America. Non-whites as a group were not my countrymen — they were my demographic enemies. They were waiting for their chance to take over once they have the numbers to do so. Knowing this made me cleave towards my own kind and my own racial identity. How could it not? It’s the natural thing to do when feeling threatened. Furthermore, I knew about the greatness of America’s past and doubted that it was unconnected to its legacy white identity.

Having established this red-pilled dichotomy, I began to take a closer look behind the curtain which was obscuring the true mechanisms of power in my country. I finally caught a glimpse at the tiny group of highly-influential people who were doing the most to support non-whites and to demoralize white people like myself. I began to do Wikipedia searches on them, and learned that there were more of them in positions of power than I had realized. Could these people really be my friends and allies like I once thought they could? Where’s the love I’d been showing them all these years, and why isn’t it being requited?

The human mind is a sluggish thing. Mental habits can become ruts, and sometimes it’s hard to see out of them. As I was researching Dissident Right ideas for my novel White Like You [4] several years back, the pressure began to mount for me to break out of the rut I had been in. But I held out. I resisted. I didn’t want to admit I had been wrong. I didn’t want to turn on the Jews. But, eventually, I did. I had no choice. With enough study, one realizes that the dissidents had been the ones possessing most of the Truth all along.

As I stated recently in my essay “Rediscovering a Song” [5]:

. . . as I was poking around the edges of the dextrosphere for information and anecdotes to put in the mouth of my antagonist, I began to realize something: the arguments from these bad-thinkers seemed to hold together pretty well. Unexpectedly well. Sure, there were some unstable and paranoid individuals out there. But for the ones that weren’t—for the ones who were merely angry or resentful yet still clear-headed—I had nothing. This made sense since they had done their homework on Jews, while I hadn’t even known that any homework had been assigned. People kept mentioning philosophers I had never heard of and historical events I never knew happened. I had never heard of the Holodomor. I hadn’t known about 200 Years Together or For My Legionaries. People kept referring to The Occidental Observer as well as Counter-Currents where I found Greg Johnson’s dissertations on Jewish power quite jarring and hard to refute. I couldn’t believe I was actually taking this stuff seriously. To put it all to bed once and for all, I decided to read Kevin MacDonald’s The Culture of Critique since everyone was talking about it. To say I went in a critic and came out a convert might be overstating it a bit. But as I was reading it, I could feel my philo-Semitic angels dying one by one. I imagined I could hear them scream.

I believe that much of the Dissident Right is about this rightward shift from race-realism to race identity to understanding the Jews. We start with biological truth, move to political truths, and then finally to forbidden truths. It’s not about hate or revenge, of course. It’s about identity. People must have identity of some sort — a way to differentiate themselves from others — or else they face swift extinction. Perhaps this is why ancient tribes living only miles apart from each other insisted on having their own gods; they needed that link to the future and the past, their alpha and omega, to tell them that they’re special, to give them a reason to keep fighting to survive. Whether against the elements, animals, Man, didn’t matter. The fight for survival is the only fight, and nothing equips us better for victory than a strong identity.

I believe white people are losing this identity — this strong racial identity. They have been on top for so long, they have forgotten what it is like to suffer at the hands of others or to live in a culture not informed by the political ideals derived and perfected by whites. To them, everyone is potentially white. Either that or they are secretly afraid of non-whites or feel so guilty about the past that they seek to deny their racial identity in order to appease them.

This kind of thinking is pathological. It is dishonest, solipsistic in the extreme, and suicidal in practice. It is this sort of thing I would like to see reversed while we still have time to reverse it.

I have shared with you how I became red-pilled, but the issue of time is why I stay red-pilled — because we are swiftly running out of it.

Spencer J. Quinn is a frequent contributor to Counter-Currents and the author of the novel White Like You [4].