The Art of N. C. Wyeth

Posted By Alex Graham On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled

N. C. Wyeth

2,062 words

Newell Convers Wyeth, or N. C. Wyeth, was one of America’s greatest artists and illustrators. Over the course of his lifetime, he created over 3,000 paintings and illustrated over 100 books, including several Scribner Classics. His son, Andrew Wyeth, and grandson, Jamie Wyeth, also became prominent artists.

Wyeth was born in 1882 and grew up on a farm in Needham, Massachusetts. His childhood was an active one, and he often went hunting and fishing with his brothers. At 17, he began studying at the Massachusetts Normal Art School and sought apprenticeships with local artists. Three years later, Wyeth was one of twelve students accepted to the studio of famed illustrator Howard Pyle, who would become his greatest influence.

Although his fame was later eclipsed by Wyeth’s, Pyle was a celebrated illustrator in his day. His primary contribution was the founding of a distinctly American style of illustration. Pyle and his students were responsible for the golden age of American illustration in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He instructed a total of 75 students in his studios in Wilmington, Delaware and Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. His students were encouraged to study American history and immerse themselves in American landscapes. Central to his artistic philosophy was a concept he termed “mental projection,” or the ability to become one with one’s subject by way of firsthand experience. One of his students became a deckhand on a ship; another became a knot maker on a whaling voyage. [1]

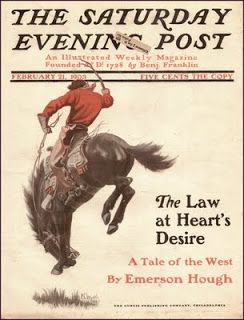

Wyeth embraced this philosophy wholeheartedly. In 1904, he embarked on a trip out West in order to gain inspiration for his work. He had already evinced a fascination with Western themes, as seen in his breakthrough illustration “Bronco Buster,” which he painted for the cover of the Saturday Evening Post when he was 20. (Three years later, he used a similar image for a Cream of Wheat advertisement.) His expedition to the West lasted about eight weeks. During this period, he worked on a ranch in Colorado and also spent time with the Navajo in New Mexico.

1903 edition of The Saturday Evening Post depicting Wyeth’s Bronco Buster.

The West was rapidly undergoing modernization by the time of Wyeth’s expedition, but the spirit of the Wild West was alive and well. Wyeth wrote to his mother: “I have spent the wildest, and most strenuous three weeks in my life. Everything happened that could happen, plenty to satisfy the most imaginative. The ‘horse-pitching’ and ‘bucking’ was bounteous.” [2]

In the early 1910s, Wyeth began to focus on illustrating classic novels for Scribner’s. Most of the books he illustrated were boys’ adventure tales, such as Treasure Island (1911), Kidnapped (1913), The Black Arrow (1916), Robin Hood (1917), The Last of the Mohicans (1919), Robinson Crusoe (1920), Rip Van Winkle (1921), The Scottish Chiefs (1921), The Boy’s King Arthur (1922), The White Company (1922), The Deerslayer (1925), and The Yearling (1939).

His 17 illustrations for Treasure Island, the first book he illustrated, are among his most celebrated works and made him famous upon their publication. They are rich with detail and drama, elevating them to works of art in their own right. Consider the illustration below of Jim Hawkins and Long John Silver, whose dramatic contrasts between light and dark evoke Renaissance art. Jim’s upward glance and boyish pose convey his childlike admiration for Silver, while Silver’s darkened face belies the innocence of the accompanying quote — “To me he was unweariedly kind; and always glad to see me in the galley” — and foreshadows Jim’s discovery of his treachery. The emotional depth of the image goes well beyond the original text.

Jim Hawkings, Long John Silver, and His Parrot, 1911. “To me he was unweariedly kind; and always glad to see me in the galley.”

Another notable illustration is Wyeth’s portrait of Captain Bones. His aggressive stance and billowing cloak speak to his larger-than-life persona. His dark figure dominates the pastel-hued surroundings, emphasizing his rough-hewn masculinity.

Captain Billy Bones, 1911. “All day he hung round the cove, or upon the cliffs, with a brass telescope.”

Also striking are Wyeth’s illustrations for The Boy’s King Arthur, a reworking of the Arthurian legend by Southern poet Sidney Lanier. The illustration below depicts the slaying of Lamorak by Gawain, Gaheris, Agravain, and Mordred.

“They fought with him on foot more than three hours.”

The most prominent characteristics of Wyeth’s illustrations as a whole are a folkish sensibility and a strong sense of movement and action. Take this illustration from Robin Hood:

Little John Fights with the Cook in the Sheriff’s House, 1921

Barnes & Noble recently attempted to celebrate Black History Month by launching new Penguin editions of classic books with covers reimagining protagonists as black people. It backfired massively. Non-white authors accused Barnes & Noble of “literary blackface” and pointed out that slapping black faces on the protagonists of classic literature would not alter the essential whiteness of the canon. Of course, they are right: classic books were written by and about white people. This is felt in Wyeth’s illustrations. The books he illustrated belong in every white child’s library.

Wyeth gravitated toward Impressionism in the 1910s (Chadds Ford Landscape [1909], The Studio [1915]). He later became associated with American Regionalism. He also experimented with modernist techniques.

In the 1920s, Wyeth began painting murals at the behest of several prominent institutions. His most notable mural is Apotheosis of the Family (1932), which was commissioned by the Wilmington Savings Fund Society. Somewhat reminiscent of Thomas Hart Benton, it depicts a white family surrounded by rolling hills and swirling clouds. The landscape encompasses the four seasons as well as mountains, farmland, and coastline. It is a paean to life, vitality, and the American people.

Apotheosis of the Family, 1932

Also worth noting are his murals for the First National Bank of Boston, commissioned upon the opening of their new building in 1924: The Tramp Steamer, Phoenician Biremes, Elizabethan Galleons, and The Clippers. Wyeth was very fond of nautical imagery.

Phoenician Biremes, 1923

Wyeth’s output also includes advertisements, calendars, and posters. His advertisements are even more reactionary than his other works. His advertisement for Aunt Jemima Pancake Mix shows the black Aunt Jemima feeding two Confederate generals. His advertisement for Lucky Strike is accompanied by the slogan “Nature in the Raw Is Seldom Mild” and depicts the Battle of Fort Dearborn, in which Native Americans slaughtered white settlers; his artwork was “inspired by the fierce cruelty of the savages whose knives and tomahawks caused the story of the Pioneer West to be written in blood.”

Nature in the Raw is Seldom Mild: The Fort Dearborn Massacre, 1932

Wyeth’s view of natives was not wholly unfavorable. He was drawn to their wild way of life. Yet one is left with the impression that he saw them as merely part of the landscape. His endpaper illustration for James Fenimore Cooper’s The Last of the Mohicans shows two natives and a white man in a canoe; the natives are seated and paddling, while the white man stands erect, scanning the horizon.

Wyeth’s best advertisement is his two-page illustrated ad for Willy’s Overland (The Overland Out West, 1914), which shows a convertible filled with cowboys next to another cowboy on horseback riding past them. The caption is “The West of Today.” Perhaps Wyeth wanted to show that the spirit of the Wild West could coexist with new inventions like the automobile.

The Overland Out West, 1914

Although some of his advertisements feature automobiles and firearms, Wyeth never really embraced the modern world in full. He remained an unabashed traditionalist throughout his life. He generally looked backward for inspiration, and the values he most treasured would now be considered quaint and outmoded.

Patriotism saturates Wyeth’s work, both overtly and implicitly. In 1930, Wyeth made two large-scale paintings of George Washington: Reception to Washington on April 21, 1789, at Trenton on his way to New York to Assume the Duties of the Presidency of the United States and In a Dream I Meet General Washington. The latter is one of his masterworks and highlights his experimentation with modernism, which began in around 1925. The painting was inspired by a dream Wyeth had after falling from a height of 30 feet while painting a mural; he dreamt that he witnessed the Battle of Brandywine while Washington narrated it. Three years prior, Wyeth and his family had witnessed a re-enactment of the battle. His son Andrew is seen drawing in the lower left-hand corner. Wyeth himself stands upon a scaffold in the foreground.

In a Dream I Meet General Washington, 1930

In 1922, Wyeth made seventeen illustrations for Poems of American Patriotism, an anthology of 70 poems compiled by Brander Matthews. He also painted figures such as Benjamin Franklin, Christopher Columbus, and Ethan Allen.

In a sense, nearly all Wyeth’s works have a patriotic dimension. They celebrate that which is local and particular and exhibit a worldview founded upon the philosophy of “blood and soil.” The description of George Bellows as “the most characteristically ‘native’ of our painters . . . because his emotions, tastes, and personal qualities remained so purely and so completely American” could also apply to Wyeth, whose works glorify American landscapes and the people who cultivate them. [3] Wyeth was a populist who excelled at portraying ordinary men with respect and dignity. April Rain (1935), Dark Harbor Fishermen (1943), and The Lobsterman (1944) are good examples.

The Lobsterman, 1944

The few remarks Wyeth made on the subject of politics indicate that he was unquestionably a man of the Right. He praised Madison Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race and supported eugenics. In a letter to his mother, he bemoaned “the inevitable direction the races of the world are taking, particularly our nation.” [4]

The greatest painting of Wyeth’s later years is Island Funeral (1939). It is one of a number of paintings by Wyeth inspired by the landscapes of Maine, where he had a home. (He named his house “Eight Bells” in honor of Winslow Homer’s painting of the same name.) One September day in 1934, he spotted a flotilla of boats headed for Teel Island, a small island off the coast of Maine where the Teel family had lived since the Revolutionary War. They were meeting to attend the funeral of the recently-deceased family patriarch, Rufus Washington Teel. The scene made a great impression on Wyeth.

Rufus Teel was a lobsterman. He was immortalized in a 1926 newspaper article whose headline reads, “Rufe Teel, 88-year-old Maine Fisherman, Has Great Time Battling Stormy Wave.” Wyeth saw him as the embodiment of American hardiness, the “perfect amalgamation of elemental nature and human life.” [5]

Island Funeral, 1939

To Wyeth, Teel’s funeral symbolized the collapse of the fishing industry in Maine and the death of a way of life. On a larger level, it represented the decline of an ethos that the rise of modernity threatened to extinguish.

Wyeth opted not to portray the scene in the manner of a typical landscape because he wanted to distance it from the innocuous, undisturbed quality associated with postcard images. Instead, it is painted from an aerial perspective.

One of the most eye-catching features of Island Funeral, created in tempera, is its rich blue and green hues. DuPont’s Jackson Laboratory provided Wyeth with pigments made from “Monastral Fast Blue B” and “Monastral Fast Green G,” which were the products of recent developments in dye-making.

Wyeth never quite achieved the recognition he sought as an artist. His hope was to make a name for himself outside of illustration and establish a reputation as a “serious” artist. His first solo exhibition, which consisted of twelve paintings, was a flop and did not have the effect he had hoped for. The event signaled the decline of his career. His fame continued to fade, particularly as his son Andrew’s success grew.

The best paintings of his later years — The Lobsterman, Dark Harbor Fisherman, Island Funeral — prove that Wyeth truly was one of America’s most significant artists. One could further argue that the artistic merit of his illustrations is often equal (or, in some cases, superior) to that of many of his other works. The pathos and humanity contained in some of Wyeth’s illustrations — his chilling portrait of Blind Pew in the moments before his death, his portrait of young David Balfour, his depiction of Little John singing merrily — qualify them as serious works of art.

N. C. Wyeth: New Perspectives, the first retrospective of Wyeth’s work in almost 50 years, will be on display at the Taft Museum of Art until May 3.

Notes

[1] Jessica May and Christine Podmaniczky, eds., N. C. Wyeth: New Perspectives (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), p. 46. https://centerofthewest.org/2015/11/01/points-west-nc-wyeth/ [1]

[2] Ibid., p. 81.

[3] Ibid., p. 65.

[4] Ibid., p. 83.