One Day as a Lion

Posted By Scott Weisswald On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,556 words

Rage Against the Machine is going on a reunion tour. How unexpected! The highlight of this roadshow, which they are calling the “Public Service Announcement” Tour, will be a series of dates played in or near infamous American border towns like San Antonio, Las Cruces, Phoenix, and the band’s hometown of Los Angeles. The band will also be donating the proceeds from their “charity” ticket sales — the tickets costing upwards of $300 that have fans enraged [1] — to immigration reform activists in each city. They’ll also be performing at some of the largest music festivals in the world, like Coachella, Lollapalooza, Reading, Leeds, Rock En Seine, and Electric Picnic.

Rage made a name for themselves in the 1990s with a winning combination of progressive politics, aggressive music, and multiple well-executed publicity stunts that ran the gamut from a boycott of Guess? (a heinous crime in the godless world of 90s fast fashion) to playing massive protest shows outside both the Republican and Democratic National Conventions.

Their music appealed to petit bourgeoise leftists and teenagers upset with their parents with equal fervor. They occupied a specific and highly lucrative niche of being inflammatory enough to anger Old, Boring People, but weren’t so daring and revolutionary as to be rejected by major labels such as Epic, a Sony imprint. RATM songs are staples of protests by tepid liberals, the music of choice of modern-day stoners to play in their Honda Civic, the band that gives a voice to oppressed, grounded children. There’s a little something for everybody in their discography.

This isn’t to say that Rage is a complete sellout band. Their members are fairly outspoken on issues that range from indigenous Mexican rights or fair labor practices, even if they have since become typical champagne socialists. Fountains of ink have been spilled about the faux leftism or pseudo-activism of popular rock music acts, and I don’t plan on haranguing about such a topic any further. What’s more interesting about Rage — and lead singer Zach de la Rocha, in particular — is that they represent one of the clearest-cut examples of how authoritarian political ideologies and the personae they attract make use of the same symbols, right or left.

This phenomenon could have a myriad of causes. One could make the rather compelling argument that our symbolism — that of power, Faustian innovation, or explosive martyrdom — is just so goddamn cool that everyone wants to imitate us. Another explanation may be that movements built around a radical ideology of any sort will have a lot in common in methods, regardless of desired outcomes. The allure of communism, fascism, or anarchism lies in their promise of placing an individual at the center of world-altering change. They are inherently futurist, rather than reactionary, and emphasize the importance of individual participation in a movement that will encompass and directly impact all of humanity. Radicalism is also a gateway to espousing the death of your enemies, an animalistic impulse suppressed by political thought that exists within the status quo.

The most likely explanation, however, lies in the leftist doctrine of “reclamation.” You’ll see this word tossed around quite a bit, whether it’s in reference to the use of racially or otherwise charged epithets by groups previously targeted by them — think “nigga” for blacks, “faggot” for homosexuals or other queer individuals — or by co-opting imagery and themes to either parody them or destroy their symbolic power. Such a thing can often bleed over into sympathy; purported “reclamation” became controversial during the late 80s and early 90s, when groups like Throbbing Gristle, Death in June, Joy Division, and others in the post-punk or industrial scene began trotting out fascist imagery during their live shows, in their lyrics, or as part of their visual aesthetic. There are still questions about how serious these groups were to this day.

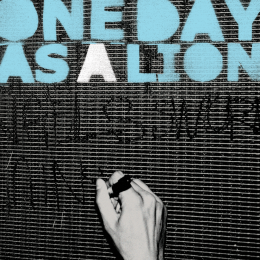

Following the split of Rage Against the Machine in 2000, each member pursued various projects in the music and art world individually and together. Rage, absent de la Rocha, formed Audioslave with late Soundgarden guitarist-vocalist Chris Cornell. Rocha, not one to be without a band, formed the curiously-named One Day as a Lion with then-Mars Volta and now-Queens of the Stone Age drummer Jon Theodore. “One Day as a Lion” might ring a bell; it’s because it was lifted directly from the Italian Fascist expression “better to live one day as a lion than one hundred days as a sheep.” The cover of their eponymous EP, released in 2008, featured the name of the band superimposed over a picture by a Chicano photographer of the same expression spraypainted on a wall.

Musically, One Day as a Lion relies on the power of its uncomfortable minor-key expressions, repetitive, almost club-like song structure, and de la Rocha’s rhythmic rap flow to create an atmosphere of high tension. Influences of early industrial, New York hip-hop, and the nu-metal that propelled RATM to fame are evident on the album. The result is several spittle-filled tracks that don’t necessarily lack production value in every instance but do miss the mark in terms of relevance, enjoyability, or the introduction of fresh sounds. Lion is more or less what Rage might have sounded like if Rocha and Morello were from Brooklyn and hung out with the Yeah Yeah Yeahs, or TV on the Radio, and almost every one of its tracks are somewhat indistinguishable. Most poignantly, however, this attempt to subvert the power of the old lion slogan goes absolutely nowhere.

“Wild International” is the opening track, centered around a stumbling buzzsaw bass riff and break drumming. Rocha raps over the top — with a characteristically wet mouth — about how the figures of Jesus Christ and Mohammed were actually globalist revolutionaries. He also throws some self-reference in, as is traditional in hip-hop, but it falls flat; Rocha is really not the individual that comes to mind when one thinks of the term “body rock.” “Wild International” is a good example of how a betrayal of songwriting form, but a commitment to messaging, can result in stilted, hackneyed final products. “Wild International” also seems to drag on far longer than its three minutes, forty-seven seconds.

“Ocean View” begins with a bit of machine-like tape noise and drumkit smashing before splitting into a harmonic-washed lead guitar and a simplistic drumline. Rocha’s vocals are, yet again, more or less unintelligible. The few words that one can make out from him are what you’d expect from him, however, like “make a rich man’s neck split.” “Ocean View” also has what may be the worst chorus of your life: It seems as though it’s desperately trying to shift into a breakdown, but is stuck on the first two beats, while Rocha nasally wails over the top, clearly pushing the limits of his non-existent range. “Ocean View” also has plainly obvious problems with its mix, with Rocha being muddied even more than his normal lo-fi style would permit.

“Last Letter” begins with Theodore pounding on a drumkit in typical garage band rhythm. “Letter” seems to take a note from “View’s” book and maintains the same meandering, squared guit-bass lead for most of the track, except for flourishes dubbed in for dramatic effect during hooks. “Last Letter” also has some misplaced drones added atop an unsettling musical salad of drumline lost somewhere between the punk, pop, and psychedelic sections of a record store. “Last Letter” also lacks clear direction, seeming mostly to progress towards its fuzzy pseudo-climax without any variation in tension on the way.

“If You Fear Dying” inverts the formula of the rest of the EP. During Rocha’s verses, the instrumental is more complex, with Theodore and Rocha shifting to one-note drilling during refrains of the almost-comical chorus: “If you fear dying, then you’re — then you’re already dead!” sung in the style of a smacked-out hardcore frontman struggling to make it through another one of his band’s 4 AM basement sets. It’s truly a musical low for both Rocha and Theodore, who are typically known in their circles and fanbases for having infectious, incessant energy. “If You Fear Dying” must have been recorded while they both were hungover.

“One Day as a Lion,” evidently recorded in the same tradition as “LFO” by LFO on LFO, is built around an alarm-clock-like, high-pitched, squeaky riff that beeps around in two tones for the entire track and is occasionally joined by another lazy, lifeless, squared-off bassline. “One Day as a Lion” might almost function if played inside a goth club after liquor hours and if Rocha’s vocals were unceremoniously removed. The pitiful chorus: “After dark, my city’s a fuse; one day, I say today, we live as a lion!” is howled atop the whole spectacle as if it were some kind of revolutionary battle cry.

One Day as a Lion may very well be an attempt to steal the fanaticism and ethos of the Fascist slogan, fashioning it into the rallying call of Rocha’s idealized, disaffected Los Angeles. After dark, however, there is no “fuse” to speak of, unless you count minorities committing property crimes under cover of darkness. The “revolution” that Rocha calls for simply doesn’t exist. There is no legion of young “socialists” ready to take the world by storm, looking toward an aging pop star for the cue. This attempt at reclamation falls flat on its face.

Rocha’s revolution may not exist; ours, however, certainly does.