Making Federal Buildings Beautiful Again

Posted By Alex Graham On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,115 words

Library of Congress Reading Room

Earlier this month, the Architectural Record obtained a draft copy [1] of an executive order that, if implemented, would have a significant impact on federal architecture. Titled “Making Federal Buildings Beautiful Again,” the order states that “the classical architectural style shall be the preferred and default style” for all new and upgraded federal buildings in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area and all federal courthouses.

The order proposes the emendation of the General Services Administration’s “Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture,” a short, three-point document written by Daniel Patrick Moynihan in 1962. In particular, it targets the second principle, which stipulates that an “official style” should be avoided and that the government should heed “the advice of distinguished architects.”

While Trump’s tastes are questionable, it appears that he has decided to defer to the National Civic Art Society on this issue. The NCAS, which promotes “beautiful, meaningful civic design,” conceived of the draft in question. Trump appointed its President to the U. S. Commission of Fine Arts in 2018. The society is also affiliated with Roger Scruton, who served on its Board of Advisors. Currently, the NCAS is involved in a project to rebuild McKim, Mead, and White’s original Penn Station in New York City, which was demolished in 1963.

Pennsylvania Station as it appeared in 1910.

Moynihan himself favored classical architecture, but he was also an anti-Communist who probably wanted to signal his opposition to Stalin’s endorsement of an official style for Soviet buildings. Stalinist architecture incorporates neoclassical elements and reflects the grandeur of classical monuments. The problem with Moynihan’s stance against the state supervision of federal architecture is that leaving matters in the hands of architects guarantees that federal buildings will reflect the tastes and opinions of elite professionals and not the American people.

Trump’s order would significantly curtail the power of the architectural establishment. Predictably, architects are furious about this. The American Institute of Architects, the Architectural Lobby, Docomomo, and the Society of Architectural Historians have all announced their opposition to the order.

Critics of the order claim that it is “undemocratic” and would stifle diversity. But the opposite is true. There is nothing is democratic about giving a rarified elite control over federal architecture. Moreover, Moynihan’s provision against prescribing an “official style” did not generate architectural diversity in the slightest — brutalism, which was in vogue at the time, became the dominant style.

The measures outlined in the order are hardly authoritarian. Trump would not ban non-classical architecture altogether and would permit “experimentation with new, alternative styles.” Alternative designs would simply have to “command respect by the public for their beauty and visual embodiment of America’s ideals” and would need to be approved by the proposed Committee for the Re-Beautification of Federal Architecture. That federal architecture should resonate with the American people is an eminently reasonable demand.

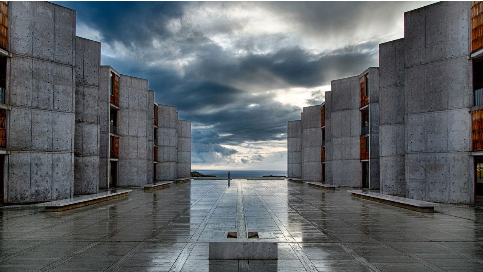

“America’s Favorite Architecture,” a list of the most beloved works of architecture in America, provides a good indication of what Americans actually like. The list was compiled by polling over 2,000 members of the general public, each of whom rated the likeability of various buildings and monuments. The top 150 structures made the cut. Most were built before the 1930s. This led critics to complain that the public’s views did not align with those of “experts” in the field. The Salk Institute, a hideous structure designed by Jewish architect Louis Kahn (born Itze-Leib Schmuilowsky), has been cited [2] as an example of a “masterpiece” that the American public failed to appreciate.

The Salk Institute for Biological Studies

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial and the World Trade Center rank fairly high on the list, but they are obviously prized mainly due to the events associated with them.

It is also noteworthy that the neoclassical West Building of the National Gallery of Art, designed by John Russell Pope, was ranked in the top 40, while the misshapen, disjointed East Building, designed by I. M. Pei, did not even make the list.

West Building of the National Gallery of Art

East Building of the National Gallery of Art

The average person may not be knowledgeable about architecture. But if the purposes of federal architecture are to inspire and ennoble the American people and to reflect our national character, then why shouldn’t the opinions of the general public be taken seriously?

It is not without reason that the Jefferson Memorial, the Capitol Building, the White House, and the Library of Congress are among America’s most beloved buildings. They communicate dignity, confidence, strength, and optimism. They embody our national heritage and give Americans a sense of identity and pride. Above all, they are beautiful and awe-inspiring to behold.

The difference between the aforementioned buildings and the federal buildings erected by the GSA during the 1960s and the 1970s could not be starker. The latter are monuments to globalism and mechanization whose dull uniformity in materials and design precludes any trace of regional character or identity. They breed unease and alienation. The elegant proportions that characterize great architecture are dispensed with and replaced by grotesque deformations that inevitably wear down the human spirit.

The Robert C. Weaver Federal Building, designed by Jewish architect Marcel Breuer and completed in 1968, is representative of the federal buildings constructed during the period following the issuing of Moynihan’s principles. As with many of Breuer’s institutional buildings, it is a curvilinear structure made of precast concrete whose monotonous façade resembles a giant surveillance monitor.

Robert C. Weaver Federal Building

Breuer was one of the first students of Bauhaus and was associated with the International Style and Brutalism. One notable event in his career was his controversial attempt to construct a modernist office building atop the majestic Grand Central Terminal, which resulted in a high-profile legal dispute that was taken to the Supreme Court. Fortunately, his plan was derailed.

The emergence of postmodernism in the 1970s marked the decline of so-called “federal modernism” and the trends it exemplified. More recent federal buildings thus reject the concrete-infused austerity of their predecessors. But whether they be “high-tech” monstrosities or boxy glass structures, they generally exhibit a similar lack of attention to beauty.

In 1994, the GSA inaugurated its Design Excellence Program intending to enhance the prestige of federal architecture. The agency has commissioned buildings from prominent architects such as Thom Mayne and César Pelli. While a few of them are compelling (Pelli’s Theodore Roosevelt Courthouse in Brooklyn, for example), most are empty fashion statements.

One of the most unsightly federal buildings constructed under the auspices of the Design Excellence Program is the San Francisco Federal Building, designed by Thom Mayne. The fact that it earned Mayne an Honor Award for Excellence in Architecture from the AIA is a damning indictment of the architectural establishment. A 240-foot-tall, billboard-like structure encased in stainless steel scrim, it possesses no aesthetic appeal whatsoever. It was designed to be as energy-efficient as possible, and no attention was paid to form (barring the clumsy addition at the top). This is ironic given Mayne’s professed hatred of all things “bourgeois,” because prizing efficiency over beauty is one of the hallmarks of modern capitalism. His preoccupation with sustainability may simply have been an excuse to construct something outlandish.

San Francisco Federal Building

Known for his habit of screaming at clients, Mayne is an ill-tempered Leftist whose designs are informed by juvenile contrarianism and misanthropy. Not coincidentally, the San Francisco Federal Building has received low workplace satisfaction ratings. While critics hailed [3] it as “daunting and dazzling,” employees have criticized its poor temperature control, lighting, and maneuverability. The building finished last in a GSA-commissioned survey measuring employee satisfaction with 22 federal buildings nationwide. (The Robert C. Weaver Federal Building is similarly hated by employees.)

The Tuscaloosa Courthouse and U. S. Federal Building is one exception to the general trend against neoclassicism. Its initial design was more typical of other contemporary federal buildings, but the judges who sit in Tuscaloosa demanded something more traditional. Modeled after the Temple of Zeus at Nemea, the courthouse is stately and dignified. Its Greek flavor is also an appropriate homage to antebellum architecture, which was heavily influenced by neoclassical architecture and the Greek Revival.

Tuscaloosa Federal Building and Courthouse

Absent from the GSA’s initiative is any recognition of the fact that federal buildings ought to inspire civic virtue and serve the common good. This is the primary purpose of federal architecture and was acknowledged as such from America’s inception until the Second World War. The idea that federal buildings should be vehicles for subjective artistic expression would have been recognized as a perverse form of individualism.

There are five main reasons why classical architecture is especially capable of serving the common good and should be preferred for federal (and municipal) buildings:

- First, it strives to be beautiful in an objective sense. Federal architecture should aspire toward objective standards of beauty in the same way that the state should aspire toward objective standards of good governance. The pursuit of aesthetic perfection is not unlike the pursuit of truth or justice. Jefferson admired neoclassical architecture for precisely this reason. (John Keats’ famous aphorism that “beauty is truth, truth beauty,” which is among the quotations inscribed on the walls of the Library of Congress, comes to mind.)

- Second, it is humanistic. The proportions that govern classical architecture are derived from nature and the human body. We find them aesthetically pleasing because they are fundamentally familiar to us.

- Third, the classical ideals of aesthetic harmony and congruity — “concinnity,” to borrow Leon Battista Alberti’s term — mirror the ideals of political unity and homogeneity. Conversely, the fragmentation that characterizes deconstructivist architecture is a reflection of modern alienation.

- Fourth, federal buildings should inspire both affection and pride. Classical architecture accomplishes this by combining beauty with strength and monumentality.

- Finally, classical architecture is associated with American identity and is an important part of our national heritage.

Another point is that classical architecture lends itself well to the incorporation of regional accents. The capitals of columns, for example, can include regional motifs. In the Senate wing of the Capitol Building are columns whose capitals depict husks of corn. The classical idiom also blends well with certain other styles. One example of this is Los Angeles City Hall, which synthesizes classical and Art Deco elements.

Grand Park and Los Angeles City Hall

The cultivation of civic virtue through architecture was the foremost aim of the City Beautiful movement, which flourished in the 1890s and the early twentieth century. The movement emerged following the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893, which boasted nearly 200 magnificent Beaux-Arts and neoclassical structures and had a profound impact on urban planning in America. The temporary city erected for the occasion, termed the “White City” on account of its buildings’ gleaming white façades, featured the works of some of America’s greatest architects, including Richard Morris Hunt and Charles McKim.

The White City

The proponents of the City Beautiful movement recognized that municipal architecture should, first and foremost, serve the public good and inspire civic pride. They believed that enriching cities with beautiful architecture would facilitate social cohesion and encourage civic-mindedness.

The most notable product of the City Beautiful movement is the McMillan Plan, which transformed the landscape of Washington, D. C. McKim and Hunt were among the members of the McMillan Commission; Frederick Law Olmstead, who had designed the grounds at the World’s Columbian Exposition, was also a member. The McMillan Plan’s most radical alteration to the layout of the capital developed by Pierre Charles L’Enfant in 1791 was its redesign of the National Mall. The plan was responsible for eliminating the Victorian landscaping of the Mall and replacing it with an open expanse of grass flanked by trees and neoclassical structures. Thanks to the McMillan Plan, the Mall is now one of the capital’s most iconic sites.

Other notable products of the City Beautiful movement include Daniel Burnham’s Plan of Chicago, the Manhattan Municipal Building, the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, the Colorado State Capitol Building, and San Francisco City Hall.

Manhattan Municipal Building

The aims of the City Beautiful movement are inseparable from patriotism for the simple reason that in order for architecture to give rise to civic engagement, it must first inspire citizens with pride in their identity. People are more inclined to behave in an altruistic manner toward those with whom they can identify and are thus more likely to exhibit civic-mindedness if they see their heritage and ideals reflected in the architecture around them.

Trump’s order will herald a revival of the spirit of the City Beautiful movement and should be celebrated. Monumental works of civic architecture in the vein of the capital’s most beloved landmarks have a unique capacity to inspire white Americans with a collective sense of pride and self-confidence, which are precisely what we need to win.