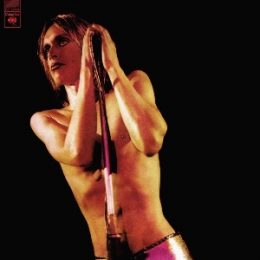

Iggy & the Stooges’ Raw Power

Posted By Scott Weisswald On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledIggy and the Stooges released the proto-punk slammer Raw Power on this day, February 7th, in 1973. It’s a raw, aggressive record that set the tone for genres as diverse in sound and era as punk, hardcore, grunge, and metal. Raw Power is also an early example of the importance of mixing and the dangers — or benefits — of studio control being handed to musicians.

The final mix was prepared by David Bowie, an impressive feat of salvage, given that Iggy Pop’s original mix consisted of three tracks in total: The entire band on one, lead guitar on another, and Pop’s vocals on one more. Controversy does remain over which mix is superior. On tracks like “Shake Appeal,” the argument could be made that Iggy’s aggressive, highly clipped rendition exudes far more energy than the cleaner Bowie mix. Other tracks on the album benefit from the clarity that Bowie’s mix afforded, as instruments and vocals that were previously indistinguishable or harsh on the ear were given new life.

Raw Power is also the first Stooges album to come after the reformation of the chronically-disarrayed band. Pop’s heroin addiction, bassist Dave Alexander’s alcoholism, and a series of failed creative endeavors in both the United States and England were sources of dejection — yet also, inspiration — for the band. Power contains some of the most expressive music of the 70s. The rebellious ethos of the album is a reflection of the times; in the 1970s, nations as historically powerful as the United States and the United Kingdom were feeling pressures both fiscal and cultural strong enough shake up their stability. Raw Power was the blueprint of the decade’s disaffection; a distinction it claimed in only 34 minutes.

For the purposes of this review, the Bowie mix will be used. However, I strongly encourage everyone who enjoys this album to give both mixes a try; just make sure to turn your volume down a bit before turning on the Pop mix.

“Search and Destroy” is the album’s opener. It’s got a peculiar sound on account of Bowie’s mix, with Pop’s voice given various amounts of gain in contrast to the muddy band. “Destroy” nonetheless has one of the most powerful rhythm sections of a 70s rock album; its dynamism is a clear influence on the soon-to-come thrash and hair metal acts of the late 70s and early 80s. In terms of guitar work, “Search and Destroy” is remarkable also for its technical prowess yet avoidance of self-aggrandizing. Gratuitous guitar solos had become commonplace in much of pop music at the time, a trend that needlessly persisted into the 80s. An avoidance of self-satisfying soloing in favor of textured arpeggiation or sheer chaos is another hallmark of the punk sound that Power helped popularize.

“Gimme Danger” follows, and it’s got a much cleaner sound than “Search and Destroy.” A highly echoed guitar hook blends with a rougher rhythm track to create a surprisingly lush soundscape. The drums on “Gimme Danger” are more subdued, acting more as a kind of low-frequency, compressed set of metronomes to guide Iggy’s frantic, nightmarish wails. “Gimme Danger” is something like a bridge between generations; the jazz and blues that dominated rock music in the previous decade plays nicely with the studio-as-instrument, thumping sound that would define highly inventive garage rock and heavy metal in the decade that would follow.

“Your Pretty Face is Going to Hell” is another one of the album’s tracks victimized by production. Iggy’s vocals are coarse and somewhat tinny — nonetheless, the caveman slams of the percussion section are remarkable accompaniments to an unceasing rhythm guitar and spastic lead. “Hell” holds tightly to its initial structure, though such a thing is far from boring. The plodding along of the band is like the tough bread of a growling punk sandwich. Pop’s unintelligibility isn’t much of a detraction from the song’s quality, either; his hoots and howls are primitive, making them both easy and enjoyable to replicate. To hear “Hell” in some dank, underground club and not begin moshing about would be the mark of incredible willpower or lamentable squareness.

The fourth track, “Penetration,” is a slower burn than the first half of the record. It does suffer from eerie vocal effects on account of the mix, which makes Pop’s spoken vulgarity a bit more hair-raising. Studio trickery elevates this to heights either uncomfortable or climactic, depending on your taste: Spun-up vocal tics, breaths, and subdued harmonization make for a moody and unsettling bit of musical catharsis. “Penetration” lacks the same force of more popular cuts. This can mean two things: This song is either intriguing background music or a taunting half-reprieve from the rest of this album’s chaos.

The title track “Raw Power” is exactly that. With little in the way of virtuosic composition, yet held together with an impressive slickness, “Raw Power” is an anthemic chunk of anarchic showboating — “don’t you try to tell me what to do” — and a love letter to the recently-matured form of “rock and roll” that the Stooges hoped to refine and condense on this record. “Raw Power” doesn’t feel self-serving, though; it’s got a stickiness granted by its smashing rhythm, and an experimental allure on account of its tortured and synthetic studio tapestries that Bowie deftly wove atop the original track. The monotone plinking of piano atop the ragtag march adds an amusing element of juxtaposition.

“I Need Somebody” has a bassier and more segmented style than most of the album. There’s a clearer influence of 60s rock here, such as the stilted songwriting of the Rolling Stones, though not without an added element of grimey rule-breaking. “Need Somebody” is probably the closest thing to a “slow” song on this album, which is certainly a breath of fresh air from how labels generally allowed albums to be created during that era. Even the most talented of songwriters often succumbed to record company pressure and stuffed their LPs with unimaginative crooning. Pop and the Stooges, who forewent mass-marketability some time ago, were not subject to these same rules. “Need Somebody” maintains panic, but provides a bit more breathing room. Such a thing is necessary prior to the ruckus of the penultimate track.

“Shake Appeal,” arguably the best track on the record, has the poundingly intense energy of a shook-up beer bottle, just waiting to explode. “Shake Appeal” maintains the same pit-shaking riff that it begins with, while Iggy screeches, whispers, and shouts over the top. “Shake Appeal” also has the record’s most inventive drumming: Occasional and furious rolls of the snare punctuate the song at seemingly random intervals, and the steadfast beat that holds the track together is simple in approach yet highly effective in practice.

“Shake Appeal” would go on to become the reference for endless garage-rock bands feeling out their first tunes. The formula of frantic energy, precise hooks, and overdriven harmonics would guide bands in every decade and nearly every Western nation, from America’s Strokes to England’s Arctic Monkeys. In short, “Shake Appeal” has shake appeal.

“Death Trip” is the final track. It’s also got some recording peculiarities, like the clipping of the lead guitar and Iggy’s fuzzy vocal track, which are difficult to ignore. “Death Trip” is a bit malformed: Its rhythm and lead sections don’t seem to play nicely with each other. Whether this is a result of poor recording, songwriting, or performance isn’t entirely clear; the lead and rhythm sections seem to be just barely out of time with each other. The lead guitar also isn’t particularly invigorating as much as it is obnoxious. For an album closer, “Death Trip” does leave much to be desired. It’s not necessarily unpleasant, but it is noticeably worse than the rest of the record.

This distinction does have some importance. “Death Trip” is a glimpse, perhaps, at what this record might have been like had Iggy and the Stooges recorded without any guidance whatsoever. Perhaps Bowie let “Death Trip” slide as a bit of an example of what happens when you let a smacked-out rock idol call the shots. After all, drug use is undeniably glamorized in music. The cocaine synthesizers of the 80s and heady heroin jams of rainy Seattle in the 90s are living (or, in many cases, dead) proof of this. But behind the drug-addled performers were always a team of handy PR guys, skilled sound engineers, and generally sober session musicians.

Absent these folks, the infectious punk-rock facade often crumbles. The Stooges certainly did — Iggy and others spent a considerable amount of time in rehab in Los Angeles following their tour’s cancellation. To write an obituary for every punk band that collapsed in on itself due to drugs, alcohol, sex, or general degeneracy would require more pages than I could possibly be bothered to type. (Maybe ask someone else?) Most importantly, it’s proof that much of this is an act, certainly not a lifestyle worth emulating. In that respect, we can pay homage to the folks that made fantastic music and art, art that we can unleash some kind of innate frustration with society to after a handful of stiff drinks. But we should never fall into the trap of treating consumer goods — which pop music undeniably is — as prepackaged identities. That is exactly what a certain group of people wants for us.

We’re white folks, first and foremost. Some of us just like screaming in our spare time.