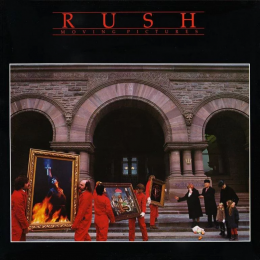

Rush’s Moving Pictures

(A Farewell to Neil Peart)

Posted By

Scott Weisswald

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

Neil Peart, the drummer and primary lyricist for the Canadian progressive rock band Rush, passed away on January 7th. He left behind an impressive legacy and has earned his place as one of rock music’s finest; his percussive and poetic prowess were central to Rush’s massive international success and changed the blueprint for how progressive rock was composed and presented during the 70s, 80s, and even 90s.

Peart displayed near superhuman stamina and innovation with his drumming. The highly technical patterns he played, often in polyrhythms with the rest of the band, were impressive on studio recordings alone. In his live performances, Peart was capable of not only replicating these feats of kit-smashing, but also embellishing upon them in the form of the dramatic drum solos that Rush’s live shows were famed for.

Peart’s infectious energy is on remarkable display on Rush’s Moving Pictures, their best-known international smash hit and perhaps most critically acclaimed record. Moving Pictures spawned the classic rock radio mainstay “Tom Sawyer” and also included cuts ranging from the narrative to the autobiographical, such as “Red Barchetta” and “Limelight.”

Moving Pictures came at a time where Rush felt comfortable both to experiment and lament. Pressures from their label, fans, and their own artistic visions are palpable on the album, whether it’s in the form of relatively short compositions (Rush’s previous work often featured incredibly lengthy tracks), personal references to the weight of fame, or the curious source material for songs such as “YYZ,” with its rhythm drawn from the Morse code pattern representing Toronto-Pearson International Airport’s call sign.

Moving Pictures appeared in 1980 and is a classic of the optimism that defined that decade, much of which is incomprehensible in the current year. But we certainly can’t fault the band for this ethos; they were both products and producers of their time, and their artistic output still holds its ground today.

“Tom Sawyer” is the album’s opening track, and likely the band’s best known in general. It has a dramatic first bar; a smash on the kick drum and a space-age synthesizer fill the ears with a tantalizing slide before Geddy Lee utters the first line and the first few strokes of lead guitar flesh out the soundscape. With just a few seconds in, the band throws down a subtle breakdown of its elements and transitions to a chorus structure. One of the commendable qualities of “Tom Sawyer” is its constantly shifting structure. Unified by just a handful of motifs, such as the glimmering synthesizer and Peart’s frenetic drumming, “Tom Sawyer” doesn’t stay in one place for too long.

Not wasting any time in sharing his philosophy with the world, Peart via Lee tells the tale of a man whose mind is “not for rent, to any god or government.” This mythical, almost demigod-like Tom Sawyer character is the ideal 80s man. He is a radically self-expressing, individualistic, anthropomorphized Chad representative of the era’s values; to indict (or not indict) him is a reflection on how you view the state of contemporary society. It’s a kind of romance one doesn’t often find in pop music, which is typically more concerned with matters such as personal relationships, drug use, or impending doom. It’s no wonder this song is so appealing to gleeful white folk; everyone wants to be a Tom Sawyer.

“Red Barchetta” is a classic tale of Man Against Society. Instrumentally, it sounds like something Blue Oyster Cult might have wrote tossed atop cocaine keyboards and buzzy, repetitive basslines. Geddy jumps between octaves describing the day a man uncovers his uncle’s well-preserved red Barchetta motorcar inside a barn from “before the Motor Law.” It’s implied that some overarching, bureaucratic power had nixed the thrill of high-speed casual motoring some time ago, rendering the immaculate red Barchetta a piece of sleek contraband. In typical libertarian fashion, such a thing doesn’t bother the narrator, who takes the machine out on the open road for a hair-raising lap in the countryside. The song’s boogeyman, police officers in hovering patrol vehicles, then proceed to chase the man down. It’s difficult not to feel entranced by such a simple narrative lacking any nuance; one feels transported to the days in which outlaw stories about raging against a government that hates fun were in fashion. Such fantasies are a kind of escapism, an easily comprehended (and enjoyed) bit of reprieve from the realities we are more familiar with nowadays. For once, let our enemy be a bunch of narcs, rather than shadowy figures eating away at our nation’s souls!

“YYZ” is a prime example of the absurd things white men will do to make beautiful art. YYZ is the IATA code for Toronto Pearson International Airport. The band played this string in Morse code, parsing the dashes as eighth notes and the dots as sixteenths. The result is an endlessly malleable motif that can be played on clinking bells (as it is in the first six seconds of the track) or on an overdriven, frantic guitar on top of organ synthesizer in 5/4 time. “YYZ” is split into several movements marked by a distinct interpolation of the YYZ Morse code pattern. Changes in melody, speed, and swing give each section of the song its own life and also serve as another example of Rush’s admirable ability to avoid boring the listener. “YYZ” switches things up every few seconds; each of its individual takes on the Morse pattern could be the hook of its own song. “YYZ” served as inspiration for many rockers after Rush; Primus used it as an inspiration on the staccato meditation “John The Fisherman,” and the song is frequently covered by bands touring throughout Canada.

“Limelight” is a topical reflection on the trappings of fame as felt by Peart. It opens with a somewhat gratuitously boomer-like guitar lick, something that would certainly get a dive bar jumping. The synthesizer on this song is more subdued than it is on other tracks, usually consigned to a compressed drone in the background. There are several moments of reverbed reprieve throughout the track that breaks up its relative monotony; this isn’t to say that “Limelight” is a snooze, but it does lack some of the variation present on most of the album’s other cuts. This is, of course, a double-edged sword; by being more repetitive and groovy, “Limelight” is therefore easier to digest. Lyrically, Lee does Peart’s ruminations on life in the limelight great justice. It’s easy for songs like this to be whiny, or out of touch, but “Limelight” comes across as simple exhaustion:

Living in a fisheye lens

Caught in the camera eye

I have no heart to lie

I can’t pretend a stranger

Is a long-awaited friend

While their sound is considered typical of the era now, it’s likely Rush did not anticipate their level of success, seeing their flavor of prog as being a little too odd for most audience’s tastes. Ironically enough, “Limelight” ended up being a fan favorite. Given Rush’s lengthy tour career, one would assume, or at least hope, that Peart made peace with the crowds.

“The Camera Eye” is Moving Pictures’ longest track, sprawling out over 10 minutes and 58 seconds. It opens with the ambience of street traffic; these car horns and voices give way to a vaguely Røykksop-esque synthesizer introduction, complete with a gently modulating rhythm track beneath. This motif repeats itself throughout the first half of the song, which also features Peart’s quintessentially technical drumming and a scale-derived guitar that trods along the top of eighth-note synthesizer; about three and a half minutes in, much of the texture is dropped for Lee’s voice and bassline to begin painting the scene of a bustling street in Manhattan. The introductory motif repeats itself yet again, separating complementary verses about hectic New York and the gentle rains that fall upon it.

Peart, never one to abandon literary convention, graces us with some foreshadowing, describing the raindrops upon New York as “English.” After another verse on the uplifting aura of American opportunity in New York, a synthesizer and drum interlude give way to the song’s original motif.

Lee then takes us on a journey throughout the historical and enigmatic London, with its Westminster mists and English pride. Peart’s lyrics are certainly describing the sublime, something especially highlighted in the lines wondering whether or not the people in the town know how lucky they are to live amongst such joyous creation. Oceans of ink have been put to paper about the Anglophone world’s twin crown jewels, and “The Camera Eye” is a welcome addition to the tradition.

Musically eerie and befitting of its title, “Witch Hunt” begins with the ominous ringing of chimes, the chanting of a crowd, and a martial pattern of drums set against sweeping synthesizer. This unsettling introduction places the listener on the edge of their seat, equal parts eager for and fearful of the harrowing tale, written by Peart, to be told by Lee. Cursed imagery of torchlit, blackened nights pierced by the uniform motion of an angry mob hellbent on destruction set the stage for another one of Rush’s almost-humorous sermons on the dangers of collectivism.

Instrumentally, “Witch Hunt” is full of drama and foreboding, but an examination of the lyrical content reveals a pile of tropes wearing a trench coat. Lee waxes operatic about a crowd “confident their ways are best,” calling for strong men fueled by “hatred and lies” to “save us from ourselves.”

In more ways than one, Rush’s music serves as a reliable touchstone for the various changes in our culture over the decades. If music with these themes were to be composed today, one of two things would happen. It would either be written off as a juvenile, septic Objectivist fantasy, or it would be praised for its transgressive attitude towards the plight of an oppressed people.

The distinction, of course, would be made on the basis of who the angry mob is meant to represent. For Rush, it’s almost certainly a lousy lot of statists. Nowadays, one would find more commercial success painting such a crowd as a bunch of neo-Nazis. Perhaps our methods of storytelling haven’t changed at all since 1980. We’re just contending with a culture a little more explicit about its desire to kill us.

“Vital Signs” is Moving Pictures’ final track, and it begins sounding something like a muffled “Baba O’Riley” on amphetamine. This introduction shifts towards a minimalistic instrumental constructed around Lee’s steadfast bass. “Vital Signs” concerns itself with a topic that prog rock never fails to address: In Roger Waters’ of Pink Floyd’s words: “The stuff that makes people go mad.”

There is a surprising amount of self-awareness present on “Vital Signs,” describing the internal strife felt by a person struggling to make himself unique in some fashion. The repeated lines, “Everybody got to deviate from the norm,” drive the point home. It’s this acknowledgement of a dangerous personal philosophy that puts Rush’s music into perspective; the gnawing urge to bolder, stranger, and more inventive than those that surround you must be what motivates Peart’s idiosyncratic songwriting and fervent drumming, Alex Lifeson’s tangled guitar work, and Lee’s androgynous voice.

Unlike many other bands of the progressive rock era, Rush never tore itself apart with drug abuse, mental illness, or crime. Peart passed away in relative peace, surrounded by family and friends after a protracted battle with cancer. All three members of the band stayed on good terms with each other, and maintained a working relationship for their entire productive lives. Why is this? Is it their acknowledgement of their ethos? Their personalities?

Or were they just one of the last nice, white* bands?

Note

* Yeah, yeah. I know about Geddy Lee.