Leftward Drift & Radical Ecology:

The Tragedy of Earth First!, Part 1

Posted By

William de Vere

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

Part 1 of 2; part 2 here [2]

While its current champions would have us believe that political ecology is the exclusive domain of the Left, and often fret about the specter of entryism by racists and crypto-fascists into their struggle for world liberation, a cursory glance at the history of ecological thought reveals the opposite to be true. Indeed, the story of environmental politics in the United States provides a textbook example of the phenomenon of leftward drift.

As many on the Right have already observed, any organization in contemporary America that does not explicitly reject the liberal pieties of our society — globalism, egalitarianism, hedonistic individualism, democratic rule — will soon find itself undone by them, neutralized by a few well-timed appeals to “equality” and “diversity.” This is commonly referred to as “Sullivan’s Law,” which posits that “All organizations that are not actually right-wing [3] will over time become left-wing [4].”

These groups often begin, sincerely enough, as a collection of like-minded individuals engaged in a project of mutual interest. However, as seemingly innocent and apolitical as their cause might seem (playing video games, saving old-growth forests, drinking Scotch), once the group achieves a certain mass and visibility it is only a matter of time before the Left takes notice. Mortified that a group of people could be going about their lives unfettered by his neurotic obsession with righting historical wrongs and destroying the last vestiges of traditional culture, the leftist will begin by critiquing the organization from outside, drawing fellow-travelers to his cause, demanding to know why the organization isn’t more diverse or active in campaigning for social justice.

Those possessing a vague familiarity with the group in question will insinuate themselves into the membership and ultimately the inner circle, exacerbating tensions in the organization that had previously been minimized by their common cause, throwing a little petty personal rivalry into the mix, and thereby sabotage the group’s ability to accomplish anything without taking a “hard look” at their inherited privilege first. They will browbeat a few of the weaker and more insecure members of the group, cultivating a small but substantial fifth column within the organization. They will call for greater democracy and transparency and inclusivity in the group’s leadership, using their newfound power to subtly undermine some of the more uncompromising earlier positions.

Once the group cohesion has weakened, the floodgates are opened to other entryists. With the aid of the original moles and fifth-columnists, these infiltrators spare little time in ousting the recalcitrant founders and members unwilling to be re-educated. Before long the original character and mission of the group will have been wholly lost, and the organization transformed into yet another appendage of the radical Left.

This is, with no exaggeration, precisely what happened to Earth First! around 1990.

Some readers will doubtless wonder why the fate of an obscure radical environmentalist group, best known for chaining themselves to trees and disabling bulldozers, should be of interest to the True Right. However, EF! in its early years was decidedly more right-leaning than is typically realized. The generally leftist connotations of environmentalism in the United States, as well as the implacable EF! it earned from corporate oligarchs and conservative state politicians, has resulted in this group being classified, wrongly, as a creature of the radical Left.

Moreover, unlike many other failed rightist organizations, the early EF! was genuinely not interested in advancing any political agenda beyond defending the wilderness against corporate greed and bourgeois complacency. To this end, in their early years they cultivated a kind of ecological Männerbund with their own myths and heroes. For these reasons alone, and because their variant of rightist ecology is one that is congenial to the Restoration, their tale — the rise and fall of one of the few genuinely anti-modern political associations in late-20th century America — should be of interest. Additionally, their takeover by hostile leftists illustrates some of the dangers of their approach.

In order to understand how this leftward drift came about, a little theoretical foregrounding is necessary. As I outlined in a previous article [5], the worldview of ecology, in its metaphysical, scientific, and political manifestations, is a contemporary iteration of the perennial doctrine of holism. This tradition of thought regards the cosmos as an interconnected whole whose integrity takes precedence over narrow human concerns, and entails a concomitant rejection of narrow anthropocentrism in the service of the natural order. In other words, rightly understood ecology shares the transcendent and hierarchical ethos that the Left has been rebelling against since the days of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution.

In addition to the danger it poses to their philosophical individualism and egalitarianism, the Left has also been historically opposed to metaphysical holism because it prioritizes the health and functioning of the whole over the parts. In politics, this tends to be rather anti-democratic, anti-individualistic and, well, totalitarian — giving rise to such glorious epochs as ancient Sparta, the Roman Empire, feudal Europe, and 19th-century Prussia (not to mention certain poorly regarded mid-century regimes). While Men of the Right might view such states as among mankind’s highest achievements, eddies of order in the historical river of chaos, for the Left they represent the ultimate evil of institutionalized hierarchy and oppression.

Though this tradition of holistic philosophical and political thought received its highest expression in Europe, there was a time when it had its devotees among the American upper classes. Nowadays the United States is often depicted as a propositional nation, a mere assemblage of atomistic economic units dedicated to liberty, equality, and unfettered greed divorced from any cultural or ethnic moorings, but this corrupt interpretation of our national character would have been unrecognizable to the WASP elites of yesteryear.

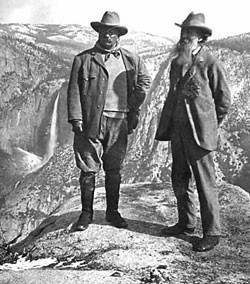

This includes the earliest defenders of American wilderness, who were square-jawed, noble-browed, broad-chested Übermenschen to a man.

John Muir, sage of Yosemite and godfather of the preservationist movement, believed the wilderness ought to be preserved for those of sufficient spiritual stuff to adequately appreciate it, and despised the influx of fat bourgeois tourists encroaching upon his holy temple.

Sigurd Olson wanted to preserve the wilds as an arena for testing the mettle of American man, growing soft and decadent with the rise of industrialism.

Madison Grant was even more explicit in his desire to preserve the wilderness as a spiritual and physical outlet for European Americans to escape from the spiritually deadening environs of the cities.

Theodore Roosevelt, bloodthirsty imperialist and Nobel Peace Prize winner, similarly preached the virtues of the strenuous life and big game hunting, and would no doubt hold the limp-wristed yuppie environmentalists of today in utter contempt.

Even their proto-ecological Transcendentalist forebears, despite the sanctimoniousness of their abolitionism and armchair radicalism, rarely ventured outside the pristine mountains and forests of New England or the lily-white village of Concord, and spent their leisure time meditating upon Indo-European masters such as Plotinus, Coleridge, Goethe, and the Vedic scribes. Historian Stephen Fox thus describes these early years of American conservation as focused towards rural areas and wilderness, strongly religious, aesthetic and spiritual in values, middle- and upper-class in sympathy, and informed by a view of history as decline and regression (1).

Despite the selective appropriation of these figures and their legacy by the contemporary environmental Left, all of the above-mentioned heroes of 19th-century conservation were in fact Men of the Right, or at least of a highly spiritualized apolitical bent. Indeed, the historical Left has never really given a damn about nature in the Right sense of the word, meaning the totality of evolutionary processes and iron laws that gave rise to an inhumanly beautiful and sublime Creation, indifferent to modernist pieties; the outer garment of God, a living symbol of imperceptible order beneath the seeming chaos of the cosmos; a world of symbiosis but also of ruthless competition, interdependent but also hierarchical, in which death and suffering are the necessary purgative processes that cleanse the Earth of its decadence and make way for new life.

A world, in other words, that can be summed up by a well-known expression of the New Right: “Nature is the ultimate fascist.” It also corresponds to the reactionary concept of “Gnon [7],” which regards Nature itself — whether consciously or not — as an implacable order that mankind contravenes at its peril.

No, the Left never had much use for that kind of nature. Karl “the idiocy of rural life” Marx, whiling away most of his hours within the monumental walls of the British Library, surrounded by one of the most polluted industrial cesspools the world has ever known, certainly didn’t care much for it. His utterly deracinated heirs in the Frankfurt School, while voicing some half-hearted concern about modernity’s oppression of man and nature, were clearly only interested in the former — and that only to the extent that Nazis and their “authoritarian personalities” could be blamed. And it is a well-concealed fact that when the contemporary ecology movement began in earnest in the 1970s, the Old Left joined voices with civil rights leaders and Students for a Democratic Society in order to vigorously denounce it for drawing attention away from the race/class/culture struggle toward such frivolities as species extinction and wilderness destruction.

However, the more astute among the left-wing organizers knew a good thing when they saw it. They soon realized that environmental concern was an easy way to buy a few votes and in short order swept in to appropriate it for themselves. This wasn’t very difficult, seeing that the purported “conservatives” of this country haven’t really been interested in conserving anything other than neoliberal capitalism for at least sixty years.

The more elitist variant of environmentalism had formerly been criticized for its doom-and-gloom politics and misanthropy, but even that proved more bearable for the majority of Americans than the self-abnegation preached by the saints of the New Left. Once the environmental movement was in its clutches, the Left could combine the best of both worlds, making middle-class Amerikaners feel guilty for both the color of their skin and for the burden their existence imposed upon the Earth. This strategy required getting rid of some of the ecological movement’s earlier, more “reactionary” positions on immigration and overpopulation, but in all honestly the Left never really had much use for those anyways.

One group stands against this tide of leftist entryism. While their glory days only lasted about ten years, until they were duly assimilated into the Borg Cube of Social Justice, Earth First! was the first activist group to reject the technocratic incrementalism of the mid-century environmental movement and embrace an uncompromising ecocentrism, which they understood as a moral and religious commitment to uphold the natural order against human greed and hubris.

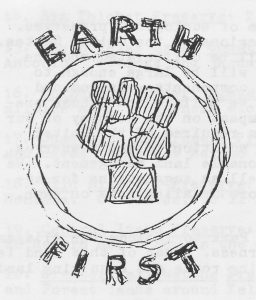

[8]

[8]The earliest Earth First! insignia, designating its commitment to fight without compromise in defense of the Earth.

Rather than focusing on mundane human concerns, ecocentrism is interested in the totality, the oikos, man’s dwelling place on Earth, both in its transcendent and immanent dimensions. Indeed, since traditional panentheistic emanationism holds that God both is in all and transcends all, ecocentrism is therefore essentially theocentrism, which is the fundamental orientation of traditional metaphysics and therefore of the True Right.

Thus, unlike most other “new social movements” that sprung up around that time, EF! received little impetus from the New Left: it was a resurgence of the elite wilderness conservation movement, deeply rooted in the mountains and forests of the Western states, and embracing a philosophy that prioritized not human welfare or socio-economic equality but a defense of ecological integrity and the natural order (2).

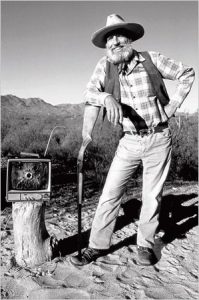

Its founders were also unique among contemporary environmentalists in their demeanor. They were more “macho” in outlook and behavior (dubbed the “rednecks for wilderness” due to their southwestern roots and inordinate fondness for beer, hunting, and chicken fried steak), more libertarian in the classic American tradition of Jefferson and Thoreau, more open to clandestine activities such as monkeywrenching, more concerned with preserving wilderness and biodiversity, and generally less interested in issues of social justice. Their influence and outlook ensured that EF! would be, in spite of its current associations, an implicitly rightist group during its first ten years.

Unlike both the contemporary environmental Left and the traditional wilderness preservation movement, EF! sought to preserve the wilderness not solely for recreational or aesthetic reasons but as an arena of natural evolution and continued speciation. Despite the New Age associations of radical environmentalism in the popular mind, these early radical ecologists upheld the laws of nature and of Gnon in all of their violence and brutality. While the workings of the natural world might seem positively hostile to its various individual organisms, the thinkers of Earth First! emphasized how these harsh realities — predation, disease, even the occasional asteroid — conduce to the beauty and health of the whole. Nature’s apparent “cruelty” is merely a product of humanitarian morality.

In addition, rather than trying to preserve ecosystems in a static state, the rightist ecology upheld by Earth First! was more attuned to the laws of nature and maintaining a civilization in harmony with those laws. As co-founder Dave Foreman said in an interview, “The idea is not to protect ecosystems frozen in time . . . but [rather] the grand process . . . of evolution . . . And so I guess what is sacred is what’s in harmony with that flow” (3).

Since humanity is uniquely capable of disregarding the laws of nature, in this rightist ecology wild, undomesticated landscapes and species are upheld as the purest and most authentic expressions of the natural order. The early EF! accordingly deemphasized the struggle for more egalitarian social arrangements, and indeed the whole emancipatory heritage of the Enlightenment, believing these to be secondary to the preservation of wild nature and evolutionary processes.

The ecowarriors of Earth First!, in fact, tended to have a rather more pessimistic view of the human species than the environmental Left, viewing ecological devastation as the work not of a few particularly destructive groups or socio-economic systems (which allows the blame to be conveniently placed at the feet of the Left’s traditional enemies), but rather as a consequence of the ideologies of modernity. They were thus deeply suspicious of progress, considering modern society “a fleeting, unpleasant mirage on the landscape rather than a vision of the future to be emulated” (4).

Accordingly, the founding principles of Earth First! included “a deep questioning of, and even an antipathy to, ‘progress’ and ‘technology’. . . For every material ‘achievement’ of progress, there are a dozen losses of things of profound and ineffable value” (5). While their resistance towards technology could sometimes veer towards a kind of brutal anarcho-primitivism, they were generally more nuanced in their appraisals, believing that a “future primitive” society combining the best of both worlds was the ideal (reminiscent in some ways of the archeofuturism [10] espoused by Guillaume Faye).

Of course, many leftist observers criticized the totalitarian or “ecofascist” potential of Earth First! stances, which prioritized the good of the ecosystem over that of individual humans. Their support for population control and immigration restrictions, apparent indifference to social justice, preference for pre-modern social orders, nature mysticism, distaste for cities, and critical attitudes toward the Enlightenment only added fuel to the fire for leftist critics (6).

Their social policies could be positively reactionary. Regarding population, for instance, Foreman argued against the leftist position that the maldistribution of resources was the problem, stating that “even if inequitable distribution could be solved, six billion human beings converting the natural world to material goods and human food would devastate natural diversity” (7).

Others argued that foreign aid to the Third World would only make humanitarian problems worse in the long run, since it artificially supports an unsustainably high population. Thus, the ecowarrior solution to global population growth outside the United States was a counsel of non-interference, letting nature “take its course” whenever disaster struck.

Leftist environmentalists also chided the ecowarriors of EF! for their anti-immigration stance. In addition to the ecological costs of our historically high immigration rate, many ecowarriors believed that massive immigration, particularly illegal immigration, serves “as an overflow safety valve to get rid of dissidents in Latin America and to provide a source of cheap, nonunion labor for corporations here at home” (8). The ever-controversial Edward Abbey also voiced concern about the demographic impacts of mass Latin American immigration. In one particularly ill-received statement, he opined that “it might be wise for us as American citizens to consider calling a halt to the mass influx of even more millions of hungry, ignorant, unskilled, and culturally-morally-genetically impoverished people. At least until we have brought our own affairs into order” (9).

Politically, the founders of Earth First! sometimes described themselves as anarchists; however, they do not appear to have been motivated by a celebration of chaos or lifestyle anarchism associated with the “circle-A” anarchists of the punk underground. A number of early ecowarriors strongly admired the Jeffersonian agrarian ideal, believing that the triumph of the Federalists and the centralized state was a tragic misstep in American history. This agrarian civic republicanism, with its emphasis on self-sacrifice in furtherance of the common good, might in fact be the only homegrown American political expression of the holistic metaphysical ideal — especially in comparison to the more atomistic and mechanistic model of classical liberalism that came to prevail after the Revolutionary era.

Accordingly, these ecowarriors embraced certain aspects of the historical American nation, frequently employing the American and Gadsden flags as symbols of their love for the land, singing patriotic songs at rallies, and holding their annual meeting on the Fourth of July. Like its 19th-century Romantic defenders, they spoke of wilderness as a particularly American heritage, with Foreman once claiming that “wilderness is America. What can be more patriotic than love of the land? We will be Americans only as long as there is wilderness. Wilderness is our true Bill of Rights, the true repository of our freedoms, the true home of liberty” (10).

In addition to betraying their more traditionalist and conservative leanings (Foreman himself was an ex-Marine and former Goldwater supporter), this flag-waving was above all an attempt to wrest the historic American nation away from the corporations and land-destroying elites, to affirm that true patriotism was inseparable from love of the land.

The founders of EF! originally hoped to spark some kind of greater social transformation; but quickly realizing that the current was against them, they evolved into a kind of ecological militia, defending the last vestiges of wild nature until the inevitable collapse of the modern world. Regarding modern civilization as wholly corrupt and beyond saving, ecowarriors saw no point in devoting much energy to movement building or working for social reforms. As co-founder Howie Wolke explained, “Thoughtful radicalism will save some biotic diversity in the short term, and allow more to be saved and restored for the longer run. Then, when the floundering beast finally, mercifully chokes in its own dung pile, there’ll at least be some wilderness remaining as a seedbed for planet-wide recovery” (11). Foreman insisted that “we never envisioned Earth First! as being a huge mass movement” and that “for a group more committed to Gila Monsters and Mountain Lions than to people, there will not be a total alliance with other social movements” (12).

In their strong early group cohesion, right-wing anarchism, and avoidance of electoral politics in favor of directly acting to defend the sacred (by illegal means if necessary), the early Earth First! might be envisioned as a kind of anti-modern ecological Männerbund. However, along with their great affinity for the historic American nation, agrarianism, and civic republicanism came one fatal flaw. Given their understandable contempt for the bureaucratic federal government, the minds of these men were captured by a persistent strain of philosophical anarchism. They therefore combined a reactionary metaphysics and political ethos with a regrettably egalitarian, non-hierarchical organization. This served to make them more popular but, unsurprisingly, would ultimately lead to their downfall.

Notes

- Stephen Fox, John Muir and His Legacy: The American Conservation Movement (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1981), 354-5.

- The following is indebted to Kyle W. Beam, “Future Primitive: The Politics of Militant Ecology,” Ph.D. diss. (University of Notre Dame, 2016).

- Bron Taylor, “The Tributaries of Radical Environmentalism,” Journal for the Study of Radicalism 2, no. 1 (2008), 43.

- Christopher Manes, Green Rage: Radical Environmentalism and the Unmaking of Civilization (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1990), 32.

- Dave Foreman, Confessions of an Eco-Warrior (New York: Crown Trade Paperbacks, 1991), 28.

- Michael E. Zimmerman, “Rethinking the Heidegger-Deep Ecology Relationship,” Environmental Ethics 15 (Fall 1993), 205.

- Foreman, Confessions, 28.

- Murray Bookchin and Dave Foreman, Defending the Earth: A Debate (New York: Black Rose Books, 1991), 27.

- Edward Abbey, “Immigration and Liberal Taboos,” in One Life at a Time, Please (New York: Holt, 1988), 43.

- EF! Journal 1, no. 7 (August 1, 1981), 1.

- Howie Wolke, “Grizzly Den: Thoughtful Radicalism,” EF! Journal 10, no. 2 (December 1989), 29.

- Foreman, Confessions, 20; Martha F. Lee, Earth First! Environmental Apocalypse (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1995), 86.