Ian Curtis:

A Northern Soul

Posted By

Fenek Solère

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

3,496 words

Someone take these dreams away

That point me to another day

A duel of personalities

That stretch all true realities

That keep calling me

They keep calling me

Keep on calling me

They keep calling me

Where figures from the past stand tall

And mocking voices ring the halls

Imperialistic house of prayer

Conquistadors who took their share

That keep calling me

They keep calling me

— “Dead Souls,” Joy Division (1979)

Just two short weeks before a traumatized Ian Curtis, the enigmatic vocalist and dithyrambic front man of Manchester’s gloomiest ever rock quartet, took his own life on the 18th of May 1980 — robbing the world of the opportunity of hearing more from one of Britain’s greatest post-punk poets — he was allegedly hypnotized by the band’s lead guitarist, Bernard Sumner, and regressed back to a past life.

The transcript of the ersatz therapy session, which Sumner reminisces about at some length in his biography Chapter and Verse (2015), has Curtis seemingly rambling on about a former existence — an incarnation as a mercenary in the Hundred Years’ War, where he would have served under bloodthirsty warlords in events like the grande-chevauchée, a raid across southern France in which an army of around 6,000 English soldiers destroyed 500 settlements and mercilessly devastated 18,000 square kilometers of territory.

One might think that’s quite a stretch for a bookish young man with autodidactic tendencies from the backstreets of Macclesfield, who was a fanatical supporter of Manchester United Football Club, prone to morbid introspection and whose song writing and bass-baritone voice were to become overwhelmingly synonymous with desolation, emptiness, and alienation. But you would be wrong. The would-be artist, who had up until that point been scratching a living in dead-end jobs with the Manpower Services Commission in Manchester’s Piccadilly Gardens and as an Assistant Disablement Resettlement Officer in the civil service, and whose musical and literary influences included David Bowie, Kraftwerk, Jim Morrison, Iggy Pop, Neu, Antonin Artaud, William Burroughs, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Friedrich Nietzsche, Hermann Hesse, T. S. Eliot, and J.G. Ballard — was not at all what he seemed.

For Curtis’s intrepid mind was trapped inside the Kafkaesque world of 1970s socialist Britain; a frozen, paranoid, and claustrophobic land where you could hear the echo of your own footsteps begrudgingly following you along the grey girder bound parapets thrown up between the fog-shrouded Eastern European style concrete tower blocks facing off against the ramshackle estates and decaying barbed wire fenced factories of the post-industrial north. A region where the chatter of the cotton-mills had long fallen silent, and manufacturing had given way once more to the lassitude of Walter Greenwood’s Love on the Dole (1933).

Curtis, a discordant and dysfunctional scribbler, was attempting to record his feelings at a time when L. S. Lowry’s painted depictions of Pendlebury in Lancashire like Going to the Match (1928), Coming from the Mill (1930), and Industrial Landscape (1955) still held true and were Muslim free — and John Tyndall and Martin Webster’s National Front could gather in their hundreds in Levenshulme and march with a strong wind at their backs under flapping Union Jack banners towards the center of Manchester along Kirkmanshulme Lane and Belle Vue.

A new Thatcherite ecosystem was on the cusp of being born, and her betrayal of the native English before the rabbinical altar of her Finsbury controllers would bring forth a creative reaction like the one embodied in Curtis’s band, Joy Division, a group that quite deliberately and irreverently took its name from a schlock horror book by Ka-tzetnik 135633 called House of Dolls (1953). This fictional Nazi sexploitation novella which purports to be the diary of a fourteen-year-old girl (in the dubious tradition of Anne Frank) details the plight of Jewish women in concentration camps being taken as sex slaves, the Freudenabteilung, by prison guards and used as entertainment in their brothels. It’s a claim perpetuated by people like Leon Yudkin in his essay “Narrative Perspectives on Holocaust Literature” and Ronit Lentin in her book Israel and the Daughters of the Shoah (2000) but whose authenticity is disputed by a key researcher of the period, Na’ama Shik, at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum. Despite this fact, the tale of exploitation still forms part of the Israeli high school curriculum.

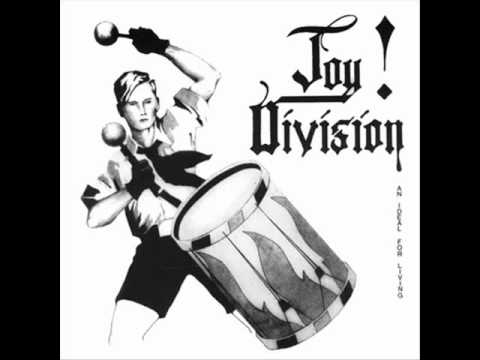

It was these controversial themes that the young and alienated Manchester musicians decided to use by releasing their first EP An Ideal for Living (1978) and a single “No Love Lost” with a cover depicting a Hitler Youth member beating a drum and a B-side entitled “Warsaw,” the original name of the band, recounting the somewhat fantastical story of Rudolf Hess trying to end the Second World War by means of his fateful flight to Scotland in 1941.

“I like it,” Ian later explained about the cover, “It’s thought-provoking.” This stance, however, did not prevent their shows from being overrun by skinheads, and were quickly and predictably followed by hints and outright accusations in the Left-leaning music press like the New Musical Express that the band supported fascism. This came at a time when Bernard Sumner and bassist Peter Hook were admitting to being intrigued by right-wing philosophy, with Sumner infamously introducing one song at a gig at Manchester’s Electric Circus venue by shouting “You all forgot Rudolph Hess!” while battles between anti-racists and patriotic working-class youths were being fought out in music venues all over the country.

The single “No Love Lost” contains lines like:

“In the hand of one of the assistants, she saw the same instrument which they had that morning inserted deep into her body, She shuddered instinctively. No life at all in the house of dolls. No love lost. No love lost.”

While the track, “Warsaw” goes:

Three, five, zero, one, two, five go!

I was there in the back stage

When the first light came around

I grew up like a changeling

To win the first time around

I can see all the weakness

I pick all the faults

Well I concede all the faith tests

Just to stick in your throats

Thirty one G, thirty one G, thirty one G

I hung around in your soundtrack

To mirror all that you’ve done

To find the right side of reason

To kill the three lies for one

I can see all the cold facts

I can see through your eyes

All this talk made no contact

No matter how hard we tried

Thirty one G, thirty one G, thirty one G

The mock-count intro is actually Hess’s prisoner number after he had parachuted into Eaglesham, and the verses recalled his part in the Beer Hall Putsch, his fascination with National Socialism and his years as a solitary prisoner in Spandau. Indeed, in Jon Savage’s So This is Permanence (2014), a collection of writings by Curtis, his wife Deborah recalls how deliberately Curtis chose every element in their home, particularly his writing room, where he would retire every night, scrawling in a plume of smoke burdened by the weight of history and creating his first-person narratives.

Other early tracks like “Conditioned,” “Crimes Against the Innocent,” “The Leaders of Men,” and “Shadowplay” make full use of references to martial images:

In a room with no window in the corner I found truth

In the shadowplay, acting out your own death, knowing no more

As the assassins all grouped in four lines, dancing on the floor

Yeah, with cold steel, odour on their bodies made a move to connect

I could only stare in disbelief as the crowds all left

I did everything, everything I wanted to

I let them use you for their own ends

To the center of the city at night, waiting for you

To the center of the city at night, waiting for you…

And The Leaders of Men:

To force a final ultimatum

Thousand words are spoken loud

Reach the dumb to fool the crowd

When you walk down the street

And the sound’s not so sweet

And you wish you could hide

Maybe go for a ride

To some peep show arcade

Where the future’s not made.

A nightmare situation

Infiltrate imagination

Smacks of past Holy wars

By the wall with broken laws

The leaders of men

Born out of your frustration

The leaders of men

Just a strange infatuation

The leaders of men

Made a promise for a new life

No saviour for our sakes

To twist the internees of hate

Self- induced manipulation

To crush all thoughts of mass salvation.

All this was followed by “They Walked in Line” from the Still double compilation album (1981):

All dressed in uniforms so fine

They drank and killed to pass the time

Wearing the shame of all their crimes

With measured steps they walked in line

They walked in line

They walked in line

They walked in line

They walked in line

They walked in line

They walked in line

They walked in line

They walked in line

They carried pictures of their wives

And numbered tags to prove their lives

And made it through the whole machine

With dirty hearts and hands washed clean

They walked in line

They walked in line

They walked in line

They walked in line

They walked in line

They walked in line

They walked in line

They walked in line

Full of a glory never seen

They made it through the whole machine

To never question anymore

Hypnotic trance they never saw

They walked in line

They walked in line

They walked in line

They walked in line

They walked in line

They walked in line

This soundtrack was produced in the stifling and sterile environment of a pre-planned decline, with all the encumbrances of economic and social decay. It was a period of deep and lasting recession that the new Tory government executed according to the road-map set out by Keith Joseph, author of Monetarism is Not Enough (1976) — who was, it was later admitted by the British Intelligence Service, in regular contact with the Israeli government during his term in office — and Nigel Lawson, Chancellor of the Exchequer, the descendant of Gustav Liebson, a merchant from Jelava in Latvia who oversaw the deregulation of the financial services industry which was a contributing factor to the financial crisis of 2007-2008. All perfectly captured in the lines from “Candidate,” off Joy Division’s first LP:

I campaigned for nothing

I worked hard for this

I tried to get to you

You treat me like this

It’s just second nature

It’s what we’ve been shown

We’re living by your rules

That’s all that we know

This sense of nihilistic ennui was only matched by the era-defining photographs of Anton Corbjin, who went on to direct and produce the 2007 movie Control, starring Sam Riley and Samantha Morton, which was based on the biography of Curtis by his now-estranged marital partner entitled Touching from a Distance: Ian Curtis & Joy Division (2005). Touching reinforces Jon Savage’s assertion that Curtis’s songs are “perfectly poised between white light and dark despair and oscillate between hopelessness and the possibility of, if not the absolute need for, human connection,” and solemnly memorializes the mood and magic of lyrics like “Isolation” from Joy Division’s classic second album Closer (1980) which reached number 6 in the charts:

In fear every day, every evening,

He calls her aloud from above,

Carefully watched for a reason,

Painstaking devotion and love,

Surrendered to self-preservation,

From others who care for themselves.

A blindness that touches perfection,

But hurts just like anything else.

Isolation, isolation, isolation.

Mother I tried please believe me,

I’m doing the best that I can.

I’m ashamed of the things I’ve been put through,

I’m ashamed of the person I am.

Isolation, isolation. . .

And “Atmosphere”, originally released on the Sordide Sentimental label:

![Joy Division - Atmosphere [OFFICIAL MUSIC VIDEO]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/1EdUjlawLJM/maxresdefault.jpg)

Walk in silence

Don’t walk away, in silence

See the danger

Always danger

Endless talking

Life rebuilding

Don’t walk away

Walk in silence

Don’t turn away, in silence

Your confusion

My illusion

Worn like a mask of self-hate

Confronts and then dies

Don’t walk away

People like you find it easy

Naked to see

Walking on air. . .

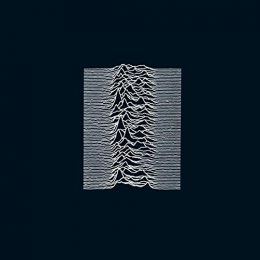

“New Dawn Fades” culminates in a crescendo of nihilistic self-doubt and self-pity. It’s one of the band’s classic cuts, soaring like funereal hymn off the initial critically acclaimed post-punk Unknown Pleasures album (1979):

A change of speed, a change of style

A change of scene, with no regrets

A chance to watch, admire the distance

Still occupied, though you forget

Different colors, different shades

Over each mistakes were made

I took the blame

Directionless so plain to see

A loaded gun won’t set you free

So you say

We’ll share a drink and step outside

An angry voice and one who cried

We’ll give you everything and more

The strain’s too much can’t take much more. . .

Below is “Decades,” the song that concludes Closer, Curtis’s own anthem to a doomed youth. His voice tinged with Spenglerian pessimism. Somber words that speak of defeat, as if he had himself just staggered off a blood-drenched battlefield, leaving the eviscerated remains of his comrades behind him in the bone bludgeoned mud. Words that reveal a mind filled with fear — terrified by the effects of his worsening epilepsy, now causing two severe convulsive tonic-clonic seizures per week — his wife having just filed divorce papers — and growing sexual and emotional insecurities relating to a fledgling relationship with Annik Honore, a Belgian journalist, music promoter and co-founder of the Les Disques du Crepuscule and Factory Benelux record labels.

Here are the young men, the weight on their shoulders,

Here are the young men, well, where have they been?

We knocked on the doors of Hell’s darker chamber,

Pushed to the limit, we dragged ourselves in,

Watched from the wings as the scenes were replaying,

We saw ourselves now as we never had seen.

Portrayal of the trauma and degeneration,

The sorrows we suffered and never were free.

Where have they been?

Where have they been?

Where have they been?

Where have they been?

Weary inside, now our heart’s lost forever. . .

It’s a bitter finale to an all-too-brief career that had once bristled with the redolent energy of a scorched-earth foot and bass pounding song like “Transmission,” recorded as a stop-gap between Unknown Pleasures, an album which Max Bell at the New Musical Express wrote “worries and nags like the early excursions of the German experimentalists” and the final Closer album, which Peter Watts describes in the Uncut Ultimate Music Guide as “an astonishing accomplishment of miserable beauty.”

Radio, live transmission

Radio, live transmission

Listen to the silence, let it ring on

Eyes, dark grey lenses frightened of the sun

We would have a fine time living in the night

Left to blind destruction

Waiting for our sight

And we would go on as though nothing was wrong

And hide from these days we remained all alone

Staying in the same place, just staying out the time

Touching from a distance

Further all the time

Dance, dance, dance, dance, dance, to the radio

Dance, dance, dance, dance, dance, to the radio

Dance, dance, dance, dance, dance, to the radio

Dance, dance, dance, dance, dance, to the radio

Well I could call out when the going gets tough

The things that we’ve learnt are no longer enough . . .

“Transmission” is a danse macabre filled with spidery guitar chords, doom-laden howitzer drumming, and lyrics that hint at Curtis having read Aleister Crowley’s Book of Thoth (1944) while attempting to evoke thoughts of Orwellian political rallies in the minds of the audience. This imagery is somewhat ironic when one recalls they naively played a Rock Against Racism gig in Leeds in the autumn of 1978 in order to break through into the mainstream.

This constant frustration exacerbated Curtis’s barbiturate driven mood-swings and heralded abnormal electrical brain activity, leading to grand mal muscle seizures by the time Joy Division were touring with the Buzzcocks in October 1979. Curtis attempted to mimic and turn these to his own advantage by developing his own unique post-pogo dance style, as witnessed in the footage from a live performance of Dead Souls from the Here Are the Young Men video.

This mesmeric and ritualistic technique became the group’s hallmark and Curtis’s own unique selling point to a rapidly growing coterie of fervent admirers. Ardent and serious minded students of Curtis’s excruciating self-dissection found hope in lines like “I remember when we were young” from “Insight” and “I travelled far and wide through many different times” from “Wilderness.” Fans and devotees saw the band’s lead singer as their only guide in troubled times, imagining they had found salvation in the interior space opened up to them in the heroic anthems created by their troubled savior.

Curtis was an icon whose body shook like a whirling dervish in the spotlight; a man palpitating gyroscopically in time with the metallic melodies being poured out in 2/4 rhythms in the darkness of half-empty halls and dank auditoriums like Eric’s in Liverpool and Rafters in Manchester, prior to dates at the Rainbow Theatre and Electric Ballroom in London, and eventually Les Bains-Douches in Paris, The Paradiso in Amsterdam and Plan K in Brussels.

Joy Division’s sets were filled with songs like “Atrocity Exhibition,” “Heart and Soul, ”“Passover,” “Colony,” and “A Means to an End.” The live performances of “Atrocity Exhibition,” based on a book by J. G. Ballard published in 1970, were described by Peter Watts as “inordinately violent” as compared to the studio version, which “has a more sustained and eerie menace, opening with Morris’s rolling drumbeat but defined by the growling and rustling effects that sound like an audience of demons from Dante’s inferno.”

Asylums with doors open wide,

Where people had paid to see inside,

For entertainment they watch his body twist

Behind his eyes he says, ‘I still exist.’

This is the way, step inside.

This is the way, step inside.

This is the way, step inside.

This is the way, step inside.

In arenas he kills for a prize,

Wins a minute to add to his life.

But the sickness is drowned by cries for more,

Pray to God, make it quick, watch him fall.

This is the way, step inside.

This is the way, step inside.

This is the way, step inside.

This is the way, step inside.

This is the way.

This is the way.

This is the way.

This is the way.

This is the way, step inside.

This is the way, step inside.

This is the way, step inside.

This is the way, step inside.

You’ll see the horrors of a faraway. . .

Curtis was also capable of penning the most sensitive and honest depiction of faltering intimacy in what some describe as the almost perfect pop song, “Love Will Tear Us Apart.”

When routine bites hard

And ambitions are low

And resentment rides high

But emotions won’t grow

And we’re changing our ways

Taking different roads

Love, love will tear us apart again

Love, love will tear us apart again

Why is the bedroom so cold?

Turned away on your side

Is my timing that flawed?

Our respect run so dry?

Yet there’s still this appeal

That we’ve kept through our lives

But love, love will tear us apart again

Love, love will tear us apart again

Do you cry out in your sleep?

All my failings exposed

Gets a taste in my mouth

As desperation takes hold

And it’s something so good

Just can’t function no more?

Love, love will tear us apart again

Love, love will tear us apart again

Love, love will tear us apart again

Love, love will tear us apart again

“Love Will Tear Us Apart” became a top 20 single following its release in June 1980, just after Curtis’s death. In some ways, it is the purest distillation of their entire musical legacy in three minutes and forty-six seconds. The title is aptly etched on Curtis’s headstone in Macclesfield Cemetery.

Epilogue

Following their lead singer’s sudden demise, the remaining members of Joy Division morphed into New Order, an electro-light pop parody of their former selves. Despite the rather interesting choice of name and the massive commercial success of the hit single Blue Monday, the group has never even come close to reproducing the rapture that was the “Joy Division experience,” a cult that continues today with people leaving offering at Curtis’s graveside and grows ever stronger with the passing of time.

The above is New Order’s take on Ceremony, one of Curtis’s true masterpieces. Below is In a Lonely Place, an obituary-like track that is shrouded in ghostly gothic mist and the immortal Mancunian’s obsessive melancholia:

Caressing the marble and stone,

Love that was special for one,

The waste in the fever I heat,

How I wish you were here with me now.

Body that curls in and dies,

And shares that awful daylight,

Warm like a dog round your feet,

How I wish you were here with me now.

Hangman looks round as he waits,

Cord stretches tight then it breaks,

Someday we will die in your dreams,

How I wish we were here with you now