My Five Favorite Books of 2019

Posted By Alex Graham On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1. Steele Brand, Killing for the Republic: Citizen-Soldiers and the Roman Way of War (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019)

This is an excellent work of military history that examines the tradition of civic militarism in the Roman Republic. Brand combines detailed analyses of battles with insights about Roman culture and society. His analysis of the Battle of Sentinum (295 BC), for instance, includes diagrams of battle formations as well as a discussion of the history of the devotio, a ritual in which one sacrificed his life in battle by charging into enemy lines. Seeing that his cavalry and infantry attacks had been ineffectual, commander Publius Decius Mus performed this act of self-sacrifice, as his father had done decades previously. The battle was a victory for the Romans.

The Roman Republic cultivated a spirit of civic-mindedness in its citizens and instilled them with the virtues of discipline, courage, and loyalty. Elites fought alongside ordinary people: after the Battle of Cannae (216 BC), Mago Barca collected golden rings belonging to fallen Roman equites and presented them to the Carthaginian Senate.

The prologue discusses the influence of ancient Rome upon the Founding Fathers. Jefferson, of course, admired the ideal of the agrarian citizen-soldier and extolled the virtues of the yeoman farmer. Yet civic militarism is functionally extinct in modern America, which is presided over by people who have no stake in the country’s future and no interest in defending it. Killing for the Republic makes a good case for reviving civic militarism, as well as the conditions that enable it to thrive.

[2]2. Michel Danino, ed., Sri Aurobindo and India’s Rebirth (Kolkata: Rupa Publications, 2018)

[2]2. Michel Danino, ed., Sri Aurobindo and India’s Rebirth (Kolkata: Rupa Publications, 2018)

Sri Aurobindo is best known for developing integral yoga, a philosophy and spiritual practice whose aim is the integration of the physical, spiritual, and mental realms and the attainment of self-perfection. His output includes works of philosophy, an epic poem entitled Savitri: A Legend and a Symbol, and commentaries on Hindu scripture. Before dedicating himself to philosophical and spiritual pursuits, Sri Aurobindo was very active in the movement for Indian independence. This volume collects his political writings spanning the years 1893-1950 and includes journal entries, transcripts of speeches, essays, and correspondence.

Aurobindo’s retirement from political life did not mean that he had lost interest in the cause of Indian nationhood, as these writings show. His later work was not divorced from his earlier activism. He equates swaraj, or self-rule, with “the fulfillment of the Sanātana Dharma” (literally “eternal order,” or Hinduism).

Aurobindo was far from the stereotype of the passive, desexed guru. Unlike Gandhi, he opposed adopting ahimsa (non-violence) as a national creed. He writes that Indians must regain the martial virtues of the Kshatriya and that “the brain is impotent without the right arm of strength.”

[3]3. William Finnegan, Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life (New York: Penguin Books, 2016)

[3]3. William Finnegan, Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life (New York: Penguin Books, 2016)

Growing up as a white boy in Hawaii in the 1960s, Finnegan was an outsider at the public school he attended and was bullied by his non-white classmates. He joined a white gang and found refuge in surfing, which he pursued with relentless devotion. This memoir chronicles his lifelong obsession with the sport, which takes him on an odyssey across the globe in search of the perfect wave.

Finnegan, a Leftist reporter for The New Yorker known for his anti-apartheid journalism, writes that his political views are rooted in his hatred of the quotidian violence that defined his childhood. Yet he is obviously drawn to violence and admits that the appeal of surfing lies largely in the lethal violence of the ocean and the thrill of risking one’s life riding the waves. He also shows sympathy for his macho blond surf partner, Domenic, who had to put up with him back when he was an “obnoxious, pretentious college student” who parroted Frantz Fanon. Interestingly, he recounts that he envied Domenic’s pride in his Italian heritage. At the end of the day, he does not have a whole lot in common with the modern Left. The younger Finnegan was a white man engaged in an obsessive quest for which he was willing to risk everything. Surfing, moreover, is inherently hierarchical (like all sports and crafts) and exclusionary (due to the perpetual threat of overcrowding).

Barbarian Days is a highly compelling memoir. A glossary of surf jargon would have been handy, but the book is quite readable overall. Finnegan’s prose is lucid and well-crafted. This is one of the best memoirs I have ever read.

[4]4. Peter Sloterdijk, You Must Change Your Life (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2014)

[4]4. Peter Sloterdijk, You Must Change Your Life (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2014)

Peter Sloterdijk is a prolific German philosopher known for his iconoclasm and his bold public persona. You Must Change Your Life deals with what he terms “anthropotechnics,” or the techniques by which humans achieve self-transformation. Sloterdijk sees humans as Nietzschean “acrobats” suspended between the animal and the superhuman, beings who possess the unique ability to turn away from the ordinary and seek something higher. All humans are “inescapably subject to vertical tensions” (from which it follows that equality is a fiction). This is most evident in domains in which the attainment of mastery demands extensive training, which he equates with religious asceticism (the ennobling kind, not the resentment-filled, servile kind criticized by Nietzsche). He argues that conceiving of asceticism as “religious” and athletic/artistic training as “secular” is misguided given that both embody the same impulse. This leads him to pronounce that religion does not exist and that religions are merely institutions that take shape around spiritual regimens.

Sloterdijk classifies antiquity as an era of practice and modernity as an era of work, identifying the latter as the result of a shift from “individual metanoia” to “the mass rebuilding of the human condition ‘from the root.’” This entailed stripping asceticism of its spiritual context, externalizing it, and dissolving it “in the fluid of modern societies of training, education, and work.” He identifies Bolshevism as the foremost example of this maladaptation.

I also recommend Sloterdijk’s The Art of Philosophy: Wisdom as a Practice, a much shorter volume in which he discusses how the idea of practice can be applied to the study of philosophy itself. It is more accessible than You Must Change Your Life, which is relatively dense.

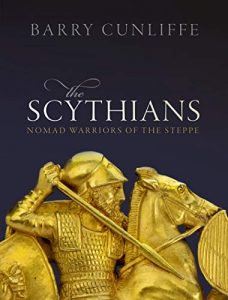

[5]5. Barry Cunliffe, The Scythians: Nomad Warriors of the Steppe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019)

[5]5. Barry Cunliffe, The Scythians: Nomad Warriors of the Steppe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019)

Veteran archaeologist Barry Cunliffe’s latest book is an impressive, richly illustrated survey of the history and culture of the Scythians, who dominated the Eurasian Steppe from the seventh century to the third century BC. Cunliffe holds that they began migrating from the Altai-Sayan region to the Pontic steppe in the ninth century BC. A Scytho-Siberian cultural continuum had emerged by the seventh century, encompassing nomadic peoples of diverse origins.

The Scythians were an Indo-European people with pale skin and Europid features. Ancient authors remarked on their light hair and eyes. They acquired East Asian admixture over time, however. This book does not discuss their genetic background at length, but a number of studies on the subject have been published in recent years.

The most elite Scythians were buried with weapons, saddles, sacrificed horses and retainers, and gold artifacts. Their metalwork is incredibly ornate and well-wrought. One striking example shown here is the gold casing of a gorytos (a case used to store bows and arrows) found in the kurgan at Chertomlyk that depicts elaborate mythological scenes. Also notable is the famous golden comb discovered in the Solokha kurgan, which was made by Greek craftsmen. Another gold artifact depicts two men drinking from a horn as part of a blood brother ritual. Scythians would mix wine with blood, dip their weapons into the mixture, and then drink from it to symbolize their loyalty to each other. They also ate the flesh of their elders in ritual meals; it was considered honorable for the elderly to die in such a fashion.