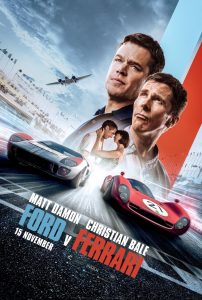

Ford v Ferrari

Posted By Alex Graham On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledFord v Ferrari depicts the rivalry between Ford and Ferrari at the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1966, and follows Ford’s quest to build a car that would break Ferrari’s winning streak. Ford tasks automotive designer Carroll Shelby (Matt Damon) with the challenge of refining the Ford GT40. Shelby is joined by Ken Miles (Christian Bale), a British driver and engineer who also collaborated with him on the Daytona Coupe and the Shelby Cobra 289.

Shelby is a quintessentially American figure: a self-made man and a charismatic visionary whose creations contributed to America’s automotive dominance in the mid-twentieth century. In addition to the Ford GT40, his company manufactured the Shelby Cobra and the Shelby Mustang. He and Miles, who has a genius for tinkering, make a great team. Both are mavericks who approach their work with single-minded obsessiveness.

The portrayal of male friendship in Ford v Ferrari is refreshingly sincere and sympathetic. Shelby and Miles spend most of their time with each other and have a close bond. There is one scene in which they wrestle each other on Miles’ front lawn. This is the best “buddy film” in recent years next to Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.

Women barely appear in the film at all. Miles’ wife, Mollie, has only one major scene, in which she screams at her husband for getting involved with a risky project and potentially jeopardizing their family’s financial security, but her face lights up when he informs her that his salary is two hundred dollars per day.

The upper management at Ford are similarly risk-averse. Vice President Leo Beebe, who resembles Richard Spencer in both appearance and demeanor, is a sly, oily character who continually tries to subvert the project and bristles at Miles’ independent nature. The conflict between him and the Shelby/Miles team is a good illustration of the polarity between modern office bureaucrats and individuals who are willing to risk life and limb to create something of value or fight for a worthy cause. It is the difference between economic man and thumotic man, or the difference between the mainstream Right and the Dissident Right.

Beebe wasn’t that bad in real life, according to those who knew him. But this portrayal of him is not entirely inaccurate; he did admonish Miles and other Ford drivers for driving too fast. He requested to have the three Fords pull in together at Le Mans because he didn’t want them to accelerate in the final stretch and risk causing a wreck. That would have given Ford a poor return on its multi-million-dollar investment.

Beebe’s decision denied Miles the unique claim to fame of winning the “Triple Crown” of endurance racing: Sebring, Daytona, and Le Mans. Miles was well in the lead, but slowed down to let the other two Fords catch up. By the end of the race, the McLaren-Amon team had traveled twenty meters farther due to the staggered starting formation, and thus were ruled to have won.

The portrayal of Henry Ford II is relatively more favorable. (Here, as usual, it is those in the middle who are the least sufferable.) Ford is shown to be more than an entitled corporate bigwig. He sheds tears of joy when Shelby takes him on a test drive and remarks that he wishes his father could have been there. Earlier in the film, he reminds Shelby that Ford used to produce B-24 bombers during the Second World War and exhorts him to “go to war.” (Over in Germany, Ford Werke made Maultier half-track trucks and the turbines used in V-2 rockets. Ford did not express opposition to the actions of its German subsidiary. Hitler was a great admirer of Henry Ford, who was awarded the Grand Cross of the German Eagle in 1938.)

All sports simulate warfare in some form. This was particularly true of sports car racing in the 1960s; it was a high-stakes, high-risk endeavor. At Le Mans in 1966 alone, there were seven accidents and one fatality. Several other cars malfunctioned and dropped out of the race.

Miles himself died two months following Le Mans, when the Ford J-car he was testing experienced mechanical failure. His 15-year-old son, Pete, witnessed his death.

Ford v Ferrari’s main flaw is that it does not fully answer the question of what it is that draws white men like Miles to this life-threatening sport, or why Miles and Shelby were so obsessed with this project in the first place. Henry Ford II’s motivation is obviously to get back at Enzo Ferrari for having refused his offer to purchase Ferrari, but Miles’ and Shelby’s motivations are underexplored.

I’m sure Miles would have uttered something approximating English mountaineer George Mallory’s famous retort to the question of why he wanted to climb Everest. Why bother to build an ultra-fast, high-performance race car with no practical purpose? The challenge is there, waiting to be met.

The highlights of the film were the racing sequences at Daytona and Le Mans, which were thrilling to watch. The cinematography in this film is excellent.

Ford v Ferrari makes no concessions to political correctness. It is a paean to white male ingenuity and ambition. One female critic indignantly remarked [2] that “Ford v Ferrari shows a generation best left dead and gone. . . . The critique I heard most often about Once Upon a Time in Hollywood could easily apply here: This is a film celebrating those nostalgic golden days when white men ruled.”

By contrast, The Aeronauts, a soon-to-be-released film based on Henry Coxwell and James Glaisher’s mission to break the record for the highest recorded ascent in a balloon – a similar display of white male excellence – eliminates Coxwell from the story entirely and replaces him with a fictional female character.

There is a message to be found here regarding America’s retreat from international competition in fields beyond sports car racing. Ford’s wins at Le Mans in the late 1960s occurred at the height of the Space Race. Both sports car racing and the mission to put a man on the Moon embody uniquely white and male characteristics. Over the past half-century, America’s performance on the global stage has declined significantly, in racing as well as in the realm of innovation and exploration. America has failed to accomplish anything approaching the significance of the Moon landing. Our best shot at making America great again is to restore the dominance of white men, a view Ford v Ferrari implicitly endorses.