The Revolutionary Army of the Infant Jesus:

Rhapsody & Repertoire

Posted By

Fenek Solère

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

We have always been concerned with the sacred or – perhaps more accurately – the loss of the sacred. We are searching for its echoes and traces which are scattered and hidden in surprising and forgotten places.

Taking their name from a fictional terrorist group in Luis Buñuel’s last film, That Obscure Object of Desire (1977), and distilling a unique blend of folk and sacred music, this mysteriously fluid and highly original collective formed in 1985. It features Leslie Hampson on percussion, Jon Egan on vocals and guitars, Sue and Paul Boyce on clarinet and keyboards, and guests such as Bill Dawson, who played free-form saxophone on tracks like “Inmaculado.” They were and still are frequently compared favorably to neofolk legends such as Current 93 and Death in June; darkwave stars like Dead Can Dance; the post-rock, experimental drone talents of Godspeed You! Black Emperor; and the religiously inspired orchestral soundscapes of Henryk Górecki and Arvo Pärt.

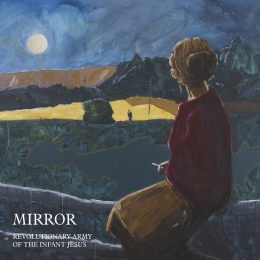

In their first phase, they released two full albums, The Gift of Tears (1987) and Mirror (1991), along with two EPs: La Liturgie, Pour La Fin Du Temps (1994) and Paradis (1995), on the Merseyside-based Probe Plus record label, which the founder Geoff Davies describes as specializing in “music to drive you to drink.” The band, which shared studios with Half Man Half Biscuit, Lovecraft, and The Farm, make use of icons and symbols from the Eastern Orthodox tradition on their record sleeves, and use clips from films by directors like Andrei Tarkovsky on the few occasions when they deign to play live.

NPR Music described [2] The Revolutionary Army of the Infant Jesus’ music as being “unburdened by sound or doctrine,” and that its credo seems to be

. . . pulled from various global folk traditions, weaving these around electronic and experimental music, but also from the traditions of the Catholic, Anglican and Orthodox churches. This is worship music which atmospherically and lyrically understands that Christianity has no bounds – and, more significantly, that even the surest faith, encompasses doubt and darkness.

This description certainly applies to their most recent release, Beauty Will Save the World (2015), which is available from Occultation Recordings [3] and Bandcamp [4]. The end of their decades-long musical hiatus was preceded by the French label Infrastition’s compilation of their earlier works on the meticulously-packaged album The End (2013), which seems to have led to their reemergence and their musical resurgence. Beauty ends with a simply stunning prayer-like track entitled “Before the Ending of the Day,” which begins with sonorous bell chimes, sweeping cellos, droning keyboards, and distant and indistinct voices that ache with desperation. Guest vocalist Jess Main begins singing a poem by St. Ambrose, the fourth-century Milanese ecclesiast:

Before the ending of the day,

Creator of the world we pray,

That with thy wonted favour thou

Wouldst be our guard and keeper now.

From all ill dreams defend our eyes,

From nightly fears and fantasies;

Tread underfoot our ghostly foe,

That no pollution we may know.

O father, that we ask be done,

Through Jesus Christ, thine only Son;

Who, with the Holy Ghost and thee,

Doth live and reign eternally.

In a rare but extremely informative interview, the band explained that

. . . the piece is a setting of a liturgical prayer which is traditionally chanted during Compline which is the last of the canonical hours (daily prayers) of the Western Church. The prayer is a call for Divine protection from the dangers and perils of the night and prefaces the beginning of the “Great Silence” within monastic communities. . . . In an ordered, intelligible and reassuringly man-made world, where we have banished the sacred and lost contact with the ineffable and the numinous, this is a text that still has the power to invoke a sense of enveloping mystery, as well as underscoring our dependence and poverty. From the outset we knew it was the concluding piece for the album, the point at which beauty leads to the threshold of eternity and where music begins to delineate the contours of silence.

After two decades of navigating those contours of silence, The Revolutionary Army of the Infant Jesus has truly burst forth into song once more. Their new album’s title is in fact a quote from Dostoevsky, who was himself steeped in the Eastern Orthodox tradition. The band explained that the impetus to reform was in order to continue their pursuit of meaning, rather than the music having a meaning in and of itself. They argued that beauty “is not created, it is discovered and restored . . . Truth is always elusive and we are still searching.”

This is quite a refreshing sentiment given the pretentions of the so-called musical ingeniis operating in the cultural industry today. They are songsters who would not have the wit or good taste to deploy the elegiac excellence of a nationalistic poet like R. S. Thomas, who was an ardent supporter of Meibion Glyndwr and of maintaining the aboriginal integrity of his homeland, into one of their compositions. This is a feat which the band accomplishes with some aplomb on their track “Bright Field,” which fuses the Welsh laureate’s poem of the same name alongside the black-and-white cinematography of Tarkovsky’s Ivan’s Childhood (1962):

I have seen the sun break through

to illuminate a small field

for a while, and gone my way

and forgotten it. But that was the pearl

of great price, the one field that had

treasure in it. I realize now

that I must give all that I have

to possess it. Life is not hurrying

on to a receding future, nor hankering after

an imagined past. It is the turning

aside like Moses to the miracle

of the lit bush, to a brightness

that seemed as transitory as your youth

once, but is the eternity that awaits you.

Such sad and melancholic ruminations attempt to capture the notion of the sacramental and the aesthetic as it converges into what the Trappist monk Thomas Merton, a mystic fascinated by the glories of Byzantium, called “the hidden wholeness.”

Wary of the music industry’s crass promotional machinery and performing – Public Image-like – behind flimsy screens so that they can only be seen in silhouette, the band maintain that they did not set out to be elusive, enigmatic, or to cultivate a Banksy-style anonymity, but concede that the introspective and inclusive nature of their collaborative efforts may have given that impression. This is a cause and effect that is certainly reinforced when listening to the celestial notes being played on a newly-issued vinyl pressing of Mirror and wondering how songs like “Joy of the Cross,” “Psalm,” and “Nativity” did not achieve the same commercial success as the New Age electronica German outfit Enigma, who topped the European music charts with their mash-up of Gregorian chants and dance beats in “Sadeness Part 1” on their MCMXC a.D. album during the 1990s. The Church Times, for whom the members of the band broke their self-imposed vow to never give interviews, producing one entitled “Standing Alone in an Apocalyptic Sea [5],” acknowledged the band’s Catholic influences, and a leading critic at The Quiteus wrote [6], “Mirror and its makers may not bring salvation, but it offers considerably more spiritual richness than any number of Ed Sheeran records, and much more besides.”

This is a claim that is difficult to deny when the listener is subjected to layer upon layer of choral chants, Pink Floyd-esque psychedelic experimentation, and Morricone-type theme music filled with a wealth of literary and cultural allusions, as in songs like “Le Monde Du Silence,” “Shadowlands,” “Hymn to Dionysus,” and “Theme De L’Homme Qui N’a Pas Cru En Lui Meme.”

As Lee Powell wrote in his interview with the band that was published at Heathen Harvest, “All is Grace [7],” their music

. . . is ‘industrial’, but it is not; it’s religious, but it’s not. Apocalyptic folk? Experimental? Heavenly? Somehow, it’s all of these whilst simultaneously being none of them. It’s the soundtrack for the end-times, radiating a beatific path that stretches far into the future. It’s music of contradictions, of warmth and solitude, of enlightenment and constraints. It’s challenging yet bewitchingly simplistic. What it does do, however, which is extremely evident throughout, is engage the listener with a sublimeness that radiates of the very essence. To try and pin a journalist tag on what RAIJ are or to pigeonhole what they produce musically is fully redundant as it needs to be experienced in its full grandeur to be fully appreciated and understood, even in part.

Though not overtly political, they do deliberately invoke a sense of a parallel and alternative Europe. The Europe they depict is a continent that is not fragmenting into a Yugoslavia-style ethnic bloodbath, or being submerged into a homogenized global consumerism that is so debilitating that whole populations seem to be intravenously fed with paroxetine-based anti-depressants so that they can continue to commute to their workplaces on a daily basis in a catatonic state of denial. Instead, the band’s music is a reminder of a more ritualistic, muscular, and chivalrous Christianity that echoes ancient verses, such as those of “La complainte des templiers”:

How many missions completed

How many engagements that the enemy constern

Through the iron of the spear to the sacred beauceant

from Syria to Provence, I served Christendom

The band confirms their manifesto by saying, “If there was any single motivation for the creation of The Revolutionary Army of the Infant Jesus, it was to create encounters with the sacred, or moments of transcendence.”

And speaking on their choice of a name:

We had an affinity with Buñuel and the Surrealists, and their project to rediscover and reassert the marvelous and miraculous. Maybe we have a different perspective and vocabulary, but we share a similar sense of alienation from a culture that denies beauty and wants to strip life of all mystery and poetry.

The name is both provocative and ambiguous, but it is also an assertion and a commitment to what our culture views as the most radical and subversive of all ideas – the sacred.

After all, as the band believes, “A society that fosters international conflict, creates and disseminates weapons of mass destruction, despoils the global environment, and presides over an economic system that is predicated on dehumanising exploitation has questionable claims to be civilized.” This puts me in mind of some lines from T. S. Eliot’s “Journey of the Magi”:

And the cities hostile and towns unfriendly

And the villages dirty and charging high prices:

A hard time we had of it . . .

And who are we to disagree – even if to us the iconography they choose may seem symbols of historic repression or degenerative corrosion – when they say, “We live in a world where we are being sold things every hour of every day, but the things we truly value are not the things we are sold but the things we discover . . .”

It seems to me, as a devout White Nationalist, that we have a duty to seek out and pursue all avenues on this great adventure to restore our people, so that our children will inherit the same birthright we enjoyed: namely, to live amongst our own kith and kin, celebrating our distinct traditions in the ethnic homeland of our ancestors, and making a contribution in thought and deed to the metapolitical renaissance in racial awareness – whose time beckons.