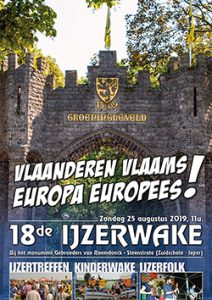

The 2019 IJzerwake:

“Flanders Flemish, Europe European!”

Posted By

Eordred

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

I would like to introduce Counter-Currents’ international audience to the largest annual Dutch-Flemish nationalist event in the Low Countries: the IJzerwake. In Dutch, this refers to a wake or prayer on the river Yser. It could also be translated as “wake of iron,” as ijzer means iron. It is a perfect example of successful nationalist activism.

The event began as a split from the older IJzerbedevaart, or “pilgrimage to the Yser,” which was taken over by Leftist influences around 2003. After several altercations, one of which involved Vlaams Blok activists beating Leftists speakers until they left the stage, the nationalists decided to leave it and started the IJzerwake to replace it. The IJzerbedevaart has since turned towards welcoming the “new Flemish,” while the IJzerwake honors the Flemish veterans of 1941-45.

The original IJzerbedevaart began in 1920 and was established by the Flemish Frontbeweging, or Front Movement, which was a group of Flemish separatists intent on strengthening Flemish influence in Belgium at the very least, if not a split with Belgium and independence for Flanders. The Frontbeweging was born in the trenches of the First World War, where the mostly Flemish soldiers of the Belgian army died for the sake of a Francophone Belgium which they had no say or representation in. It was yet another example of failed multiculturalism, one might say. To this day, the IJzerbedevaart is primarily a memorial for the war dead and a statement in favor of Flemish independence.

As a wake, it is taken very seriously. The proceedings always open with a Catholic mass, and some clergy from the Church’s more traditional flank attend. A minute of silence is held for the dead, and the three most important songs of the united Dutch people are sung: “Die Stem van Suid Afrika” for the Boers in South Africa, the “Leeuw van Vlaanderen” for the Flemish, and the “Wilhelmus” for The Netherlands.

Pro-Flemish politics has always had strong ties to the far Right. In the 1940s, they were accused of collaboration with the German occupiers, and today their primary political representatives are to be found in the populist, Right-wing Vlaams Belang party. Flaminganterij has grown from being a small movement of veterans in the 1920s to including the two largest Flemish parties, the Nieuw Vlaamse Alliantie (N-VA) and Vlaams Belang. Vlaams Belang’s leadership usually attends the IJzerwake, whereas the N-VA prefers to keep some distance.

The most important organizations at the IJzerwake include the Nationalistische Studentenvereniging (NSV, the Nationalist Student Union) and the KVHV (the Catholic Student Union), which are the only two openly nationalist and conservative student unions. Many Flemish politicians started their careers in one of these organizations, including Filip Dewinter, perhaps Vlaams Belang’s best-known face internationally, and Tom Van Grieken, its current leader. Then there is the VNJ (the Flemish National Youth Wing), which is a scouting and youth group for children aged 6 to 18. Voorpost, the uniformed militant wing of the Flemish movement, is omnipresent, and is responsible for doing most of the logistics and security at the event.

An old comrade of mine documented the 2017 IJzerwake for Red Ice, which will give you a general idea of what it’s like:

The IJzerwake is very much ethnonationalist, with speeches decrying Islamization, mass migration, and calling for Volkssoevereniteit (sovereignty for the people). Almost every year there is a call for unification with The Netherlands in a Greater Netherlands, or Dietsland. The Diets Gedachtengoed is quite common among Flemish and Dutch nationalists, who argue that Belgium is a rump state and that all Dutch people should be united in one country. The flag of this movement is the orange-white-blue, as opposed to the Dutch red-white-blue. Some of the themes of the past nineteen IJzerwakes speak for themselves:

2012: Omver en Erover – “Up and Over,” in this case meaning the Belgian state.

2016: De Maskers Af – “Masks Off,” which introduced more openly ethnocentric rhetoric, something which has continued.

2018: Volk wordt Staat – “People, Become the State!” Volk is always used in an ethnic sense.

This is an event where one can readily buy copies of the Flemish Eastern Front veterans’ magazine, Berkenkruis. Not infrequently, controversy erupts over the honoring of soldiers who died in the Second World War alongside those of the First, despite the fact that most of the Flemish see no great contradiction in this. Both fought for Flanders, and whether this was done in service to the Belgian state or to the Germans makes no difference in terms of their intent. This is not to mention that no well-intentioned patriot has ever opposed battling Communists.

This controversy has never led to disruptions by the antifa, however. Partly this has to do with the size of the event, as it has between 3,500 and 5,000 attendees most years. The 2019 event had 4,000 attendees, of which about a hundred are uniformed Voorpost security. Another reason is the location. It is held near the old First World War battlefields: Ypres, Paschendaele, and so on. Thus, it is surrounded by military graveyards, and far away from the big cities and most public transportation. This means that even if the Left could mobilize a large enough force to counter-demonstrate, getting them there would be a problem. Lastly, it is held on private farm land, and thus legally speaking it is a private event.

Maybe the Americans could learn a lesson from this. Try getting a plurality of movements to work together, rather than combine into one. Do not organize in urban Leftist strongholds, but in Right-wing strongholds in the countryside. And give it about a century, because that is how long it took for the Flemish nationalists to go from a small minority movement to dominating electoral politics in the region.

Here are some photos of 2019’s event [3] at the ethnonationalist Flemish Webzine React, for which I also write.