Kemono Friends:

Adventure in Japari Park

Posted By

Buttercup Dew

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

Kemono Friends is a clever twelve-episode anime that revolves around an adventurer, Kaban, and her attempts to find out where she belongs in the mysterious, sprawling and derelict “Japari Park.” Airing January through March 2017, it’s since become a surprise hit and amassed a cult following thanks to its effective storytelling and “strange deepness [2]” that makes it more compelling than first impressions may suggest.

Originally, Kemono Friends occupied a graveyard timeslot of 1:30 in the morning, and the languid opening episodes make it a difficult watch for children, yet the shows premise and appeal make this a “kids’ show.” Kemono Friends belongs in the special category of animation that is neither for children or adults specifically, but offers emotional depth to adult fans of the genre and cheerful edutainment to children wanting an engaging cartoon; cleverly, as each animal girl is introduced, a telephone interview with a zookeeper providing a little context about that animal’s preferred habitat and habits is included as an aside.

[3]

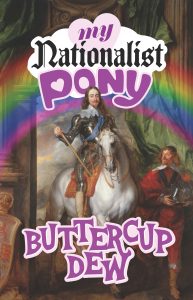

[3]You can buy Buttercup Dew’s My Nationalist Pony here [4]

The extreme contrast between the inhabitants and central characters of the Japari Park – colorful, wisecracking animal girls with simple problems for the protagonist to solve – and the underlying narrative driver of rootlessness and journeying to a place that may not even exist – makes Kemono Friends something of a conundrum. Even more so, within the logic of the Japari Park world, the darker, sadder reveals and plot twists all make sense; they aren’t simply thrown in for the sake of it, but are part of the architecture of what defines the show outwardly.

The show, Kaban’s journey, and the viewer’s engagement with the story all begin with Kaban waking up in the middle of a savannah, with no recollection of who she is or how she got there. Our female protagonist gets her name from being named “Bag” (Kaban) by Serval, the first animal girl she encounters (“Please don’t eat me!”). A Western (Jewish?) cartoon comedy writer would probably be tempted to name our hero “Jane Everywoman” or suchlike (like Michael Crichton’s “Casey Singleton” in the novel Airframe), but satisfyingly our heroine is simply called “Bag” throughout, varying between Bag, Bag-chan, and Kaban depending on production politics with translators. The opening episode is simply dialogue and a small fight scene with a “Cerulean,” one of the monsters which inhabit the Park and threaten the settled life of the all-female cast.

Introduced with just Kaban, Serval-chan, and a non-descript monster in a simplistic savannah backdrop, the much-disparaged shoestring budget 3D CG animation is incredibly apparent and hard to ignore. Yet the strength of the storytelling overcomes this, and it becomes part of the show’s charm, and its reductive scrappyness just increases the native appeal of the characters. They are memorably designed (and should be, with the wealth of the animal kingdom to draw on) and are animated with respect to their natures: Kaban-chan grasps her rucksack straps and presses onward with a tireless march; Serval-chan lopes along more energetically; and Tsuchinoko, an animal girl based on a mythical, snakelike creature, clops around on single-tooth wooden sandals (Tengu Geta) in a clever nod to Japanese folk culture. Adorably, White Rhinocerous appears in full Samurai armor. If you can let go of the fact you’re watching a low-budget anime adaptation of a failed mobile game, then the variety and development of the “Friends” makes their world all the more immersive and believable.

The animal girls are only human-ish, sentient, and talkative, yet stuck in a halfway house between their animal origins and being truly human; Bag-chan is the only human present in the Park (with the rest missing, perhaps dead) and journeys through its different zones to find her own tribe. She enables the animal girls to overcome their problems with her inventiveness, solving mysteries and improving the lot of those she encounters. They are all Friends, yet still Other – Friends made on a personal quest to destinations unknown, and not the type one can permanently settle with (though it is suggested that Bag-chan and Serval make a home for themselves by Prairie Dog and Beaver, who end up cohabiting).

Through this, Kemono Friends powerfully analogizes anomie [5] and the sense of estrangement from one’s surrounding society, making it an unsurprising and perhaps sure-fire hit in the West receptive to niche anime; the show begins and ends with Bag-chan’s experience as someone without a memory or connection to her origins. As this subplot intensifies and more of the ruined world is excavated by Kaban’s journey, there are moments of profound loss and separation. There are unsettling scenes of saying goodbye to dear friends and death, or something very much like it. All of this is handled with intense sympathy for both the cast and viewer, and the show does not rush past these critical junctures nor dwell on them, but like any good mystery show, reveals the past through the characters’ experiences and leaves the viewer to absorb the ramifications. It’s a testament to the show’s quality that these explicitly adult themes are handled so well and carry much more emotional weight than other superficially “adult” anime, with much more explicit content and played-out tropes.

There’s a degree to which Kemono Friends is almost perfectly racist. Our world and the Japari Park are full of people very different from us and inherently so, who are puzzling and have all sorts of quirks and radically different inner lives from what we experience. In Japari Park, they collectively make a group of Friends, but ours has much more brutal group competition. However, we can share with Bag-chan the experience of knowing other types of creatures, respecting them as perfectly nice and capable of magnamity and earnestness, but always with the caveat that they are separate, differentiated, and unable to make common ground on the deeper level of biological ownness. Bag-chan, in a strange, sad way, is always alone throughout the series.

But, just as Bag-chan shoulders the burden of being alone and distinct (she is rarely shown not carrying her overfilled and obviously heavy rucksack), the show leaves unanswered what were to happen if Bag ever found a human group. Would she have a place in it? Would she even have a name? Would anyone care about her, or would she be an unwelcome interloper and a strain on an already creaking society? Would she eventually turn her back on it to return to her prior identity and first experience of life as Bag-chan?

Bag-chan is estranged from her history, a girl who simply wants to go home. This sense of loss for something that may not even exist is what drives her. Like the romanticized ocean in Yukio Mishima’s The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea, there is something admirable and grand about Kaban and her journeys. The world is ruined, it has danger around every corner, and it is full of unfathomable creatures, dubious allies, and mysterious happenings. By the end of the series, when Kaban has uncovered enough mysteries to resolve the initial confusion, what propels her forward is the Grand Cause, the fullness of unexpressed feelings: distant shores and the call of the unknown, “glory to fashion of his destiny something special.” Home for Kaban is something hypothetical and radiant, brought about through tenacity and departure.

In this sense, Kemono Friends is a Right-wing show, a quest for identity and belonging, even in the face of apocalyptic circumstances and uncertainty.