Aquaman & the Revenge of God’s Chosen Fish People

Posted By Buttercup Dew On In North American New RightAquaman was perhaps the closest thing to a fulfillment of Kantbot’s promise that Trump would raise Thule, and Atlantis [2]. In order to give Aquaman a saleable “mythic resonance,” it unavoidably has to draw on Greco-Roman mythology and showcase what is bemoaningly called White Male Power. Whilst a 2018 film, Aquaman seems to belong to the late ‘90s in its casting and racial attitudes, and the screenplay has all sorts of lines that describe an interplay of Aryan and Judaic values.

What makes Aquaman especially quirky is how much these are stressed as character motivations when the film would have been perfectly serviceable without them. The film “subverts expectations” by inverting or subtly satirizing the anti-white Hollywood tropes about heroic negroes and megalomaniacal white villains – both of which we are so accustomed to that we expect them as the norm. It is a little generic and predictable in regards to plot and pacing, but the action and settings are wonderfully varied and the characters entertainingly goofy. Aquaman is a thrilling comic-book film, one where costumed super-dupes with names like “Black Manta” and “Ocean Master” become believable and engaging despite their inherent absurdity.

The soundtrack recalls Daft Punk’s electronic orchestral score for Tron: Legacy, as do the vivid colors and neon-trimmed submarines of Atlantis. The film very finely balances delivering genuine emotion and character development with the unavoidably juvenile flashiness of comic-book characters. Dialogue is snappy and there are sharks with frikkin’ laser beams attached to their frikkin’ heads; Atlantean water-breathers wear plastic armored jumpsuits that function as aquariums for their excursions to the surface. Worth watching once and no more, Aquaman goes beyond a simple action movie and gives more than a cursory exploration of masculine virtue and royal responsibility.

Aquaman himself is played to gritty perfection by Jason Momoa, of Hawaiian and German descent, who within the first half-hour is accompanied by introductory heavy metal power chords to emphasize his Atlantean Awesomeness, virility and sculpted pecs. Aquaman is of course a close analogy to Neptune, and makes use of the “Sacred Trident” of Atlantis, which confers the right to the throne. The older Neptune may indeed be “King Atlan,” who relinquishes the Trident to Aquaman (if you consider this obvious plot point a spoiler, you have probably never seen a movie), who then becomes clad in tunic armor made of gold scales. Jason Momoa’s delivery is hopefully relatable for and inspiring to young white men; he begins as something of an embittered dropout, resentful of Atlantis, whom he believes killed his mother. Whilst not an exact analogy for a young man stuck in a poor predicament and resentful of wealthy Boomers, his destination is the same: getting drunk for leisure and trying to make oneself useful where one can. In Aquaman’s case, this is just being generally charitable and doing superhero things; for a modern man, it probably means giving to charity and trying to live a “good life.” The commonality is individualization and having become unwoven from ancestral threads and the fabric of a caste society. Thankfully, Aquaman still has his dear old dad to pal around and drink with, who is keener on Atlantean fairy tales and family history than he is. Nothing really gets going until he is drawn by circumstance into having to re-engage with Atlantean civilization beyond just making use of its genetic gifts. It is through taking up his birthright and becoming King of Atlantis that he puts a disastrous war on hold between the Atlanteans and humankind. More specifically, he only achieves his potential and overcomes the trials that define him when he becomes a custodian of his civilization.

[4]

[4]You can buy Buttercup Dew’s My Nationalist Pony here [5]

The film opens with Aquaman’s dad Tom finding Atlanna, Queen of Atlantis, injured and washed up on his lighthouse shore. He rescues her and nurses her back to health, and mutual romance produces a three-quarters white couple. Atlanna is played by a very Nordic-looking Nicole Kidman, and Tom is played by the Maori, Scots-Irish Temuera Morrison. This way the film carefully skirts accusations of white supremacy by depicting Aquaman as of dominant white ancestry, but with an implied Polynesian admixture to identify him with tropical climes, shores, and adventure. With possibly intentional film hue changes, the rather dusky Temuera passes for being ambiguously white in the domestic scenes – outside in his lighthouse keeper’s beanie, his Maori admixture becomes more apparent. It also means the film can get away with showing a white woman (a blonde, even!), heavily pregnant. The anti-goyisch slant of Hollywood ensures that white women pregnant with white children on the silver screen are vanishingly rare – even the space adventure flick Passengers, devoted entirely to the romance between Chris Pratt and Jennifer Lawrence, ended up a sterile partnership.

As for Aquaman himself, he is calculated to appeal to white teenage boys as an older brother figure. Rippling with muscle, bearded and with a voice that’s just too gravelly, Aquaman was perhaps a critical flop because the review industry didn’t want the youth to look at the towering Jason Momoa duffing up a negro pirate (“Manta,” played by the laughably-named Yahya Abdul-Mateen II [Yaya-Fuszji!]) and thinking “That’s me” – especially since Yahya’s name proves how badly assimilation has worked in America and how desperate “people of color” are to re-tribalize and repudiate the cultural norms and identity of the white majority. Talking of white Americans (the only real type of Americans, really), the trope of the violent and impulsive redneck is subverted neatly in a bar scene where Aquaman (“fish boy”) is asked for his autograph by an ambiguously gay pot-bellied prole. It is funny, but reflects the fact that whites have been vulgarized and that we are kept at a proletarian level. To express ourselves as aristocratic through caste and class differences demands that we have our own exclusive spaces – something completely verboten by the system of kosher supremacy we live under. The system is dedicated to re-framing racial differences as questions of economic class, offering the communitarian classlessness of welfare, opiates, and easy sex as pacifying agents – in the TV series Supergirl, a bug alien employed as a truck driver is confronted by unionized white American workers. They are told this literal insect is “a worker, just like you.”

[6]

[6]You can buy Dark Right: Batman Viewed from the Right here [7]

Black Manta is introduced with his father and a bunch of white and Asian sub-aquatic henchmen taking command of a Russian sub (an all-Somali pirate brigade would be out of the question, despite its authenticity). He machine-guns the unarmed technical crew and slaughters the Captain in cold blood. Aquaman breaks in and dispenses rough-and-tumble justice, bashing the armed pirates about with his bare fists and a metal hatch door. Aquaman has even found time to brush up on his Russian, and greets the crew (“innocent people”) in their native tongue – dialogue which is unthinkable for a Jewish screenwriter with a phobia of Cossack pogroms or Russian “election meddling.” Throughout, Aquaman has the easy confidence of a man who has found that strength, charm, and stoicism allows one to coast through life with relative ease, something Momoa probably had little difficulty bringing to the big screen. In order to try and offset showing a black as a murderous villain, Black Manta has white character traits imposed onto him to such an extreme that it’s farcical. He risks his own life to rescue his father after foolishness traps him under a torpedo in the sub that’s going down – Aquaman leaves them to “ask the ocean for mercy” – and his father has to force him to save his own skin. Black Manta is driven from then on by a desire for revenge. It’s far less believable than an Aryan naming himself Ocean Master (the brooding and handsome Patrick Wilson) and strutting around in a cape. African-American blacks have a single-parent household rate more than double that of whites, and it’s simply not negro nature to form nuclear families or practice father-son mentorship. Impulsive blacks always have been and always will be easy come, easy go with regards to partners. The extreme levels of black abortion in the United States keep their lack of conscientiousness hidden from view, something that makes the racial coexistence of a black underclass and the increasingly squeezed white middle (dictated to by a Jewish or cosmopolitan elite) precariously possible.

[8]

[8]You Can buy F. Roger Devlin’s Sexual Utopia in Power here [9]

Manta’s dialogue also continually apes white sensibilities: He quips that the Russian submarine crew, having locked themselves in a safe compartment, have decided that “discretion is the better the part of valor.” Normally, blacks are busy expanding ebonics with new and exciting grammatical errors, but Manta clearly prefers the European literary canon. He even invokes H. P. Lovecraft – arising from the ocean in his sub-nautical steampunk exoskeleton, he exclaims, “Loathsomeness waits and dreams in the deep, and decay spreads over the tottering cities of men,” something deliciously ironic from the witless (or perhaps knowing?) screenwriters, given that Lovecraft wrote [10] “[t]he negro is fundamentally the biological inferior of all White and even Mongolian races,” and that “the Northern people must occasionally be reminded of the danger which they incur in admitting him too freely to the privileges of society and government.” Twice in the movie – and out of character for any African-American – Black Manta rejects bribes of gold from King Orm, saying “killing him is my reward,” indicating he holds honor (or at least a rudimentary version of it) higher than bling. Like many other Positive Portrayals though, he is an accomplished handyman at reverse-engineering a plasma cannon – if only rural Africans were really this clever, the Wakandan Air Force wouldn’t have the trouble it does getting off the ground.

[11]

[11]You can buy Return of the Son of Trevor Lynch’s CENSORED Guide to the Movies here [12]

Aquaman’s sidekick and love interest, Princess Mera, is a redhead – in 2019, redheads are facing extinction on the movie screen as well as in Bonnie Scotland, thanks to the dysgenic Left-wing obstinancy in both cases. The red is a glaringly artificial hue, perhaps meant to seem like an Atlantean jellyfish, but it’s red nonetheless, unlike the Spider-Man franchise’s erasure of the copperhead Mary-Jane (Kirsten Dunce) with plain-as-mud Zendaya. The obligatory romance is the weakest relationship in the film, unlike the tear-jerker reunion between Aquaman and Aquamom.

Most interesting is the principle villain King Orm (later, Ocean Master). Manta is but a foreign mercenary he employs to settle the squabble for the throne. Aquaman’s half-brother and second in line, he is the son of Atlantean patriarch King Orvax and Queen Atlanna, a “high-born” who can breathe both air and water. Aquaman himself is excoriated repeatedly for being a “half-breed bastard” or “abomination.” Is King Orm the Nazi brownshirt obsessed with racial purity that has to appear in each and every movie? Apparently not; instead, he is more of an environmentally-minded preservationist concerned with the surface-dwellers poisoning the waters and slaughtering the whales. His desire is to “scorch the surface,” as “Atlantis is many wonderful things, but forgiving it is not.” When Aquaman, raised on the surface and saturated from birth in American liberalism, trounces him in their final duel, he displays magnanimity: “Yield the throne.” Yet Orm is a staunch traditionalist and desires to die: “Forgiveness is not our way!” In other aspects, King Orm is firmly white, polytheistic, and honor-bound. He agrees enthusiastically to trial by combat twice: “By bloodshed do the gods make known their will!” His aim is to unite the fallen polities of Atlantis through force and cunning into an imperial whole under his command (“The king is dead. Long live his heir”). He cuts a sort of Alexander the Great figure, one that wants to bring a vast area under his singular rule even at the cost of racial contamination and panmixia. The masses of Atlantis don’t feature much in this action flick (nor do they need to), so we cannot know anything about Orm’s true attachment to the nation; only that he venerates the imperial lineage and heritage of his forebears – but not so much so that he is above destroying it in a false-flag attack.

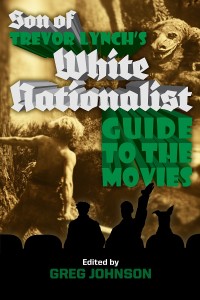

[13]

[13]You can buy Son of Trevor Lynch’s White Nationalist Guide to the Movies here [14]

Whilst subterfuge and deceit can be expected from a white man with ambitions of empire, the obsession with vengeance and bloodshed struck an altogether more Judaic note, as Jews are characteristically vengeful and inhumane to their enemies – perhaps their most prominent trait. Jews, in presuming to speak for all of humanity through Tikkun Olam, “invoke it, monopolize it” and “display a shocking pretense: to deny the humanity of the enemy [and] declare him outside the law and outside of Humanity, and thus ultimately push war to the extremes of inhumanity [15].” Jewish identity and Judaic morality centers on being a persecuted minority. The Jewish diaspora strategy of maintaining a strict separation from a host society whilst exercising the privilege of citizenship and infiltrating it at levels of cultural and political agency unavoidably relies on a phobia of their hosts. This contributes to a Jewish neurosis about the abuses that are just waiting to be unleashed should Jews ever relinquish their grip on the levers of power. Pew Research shows [16] that “Remembering the Holocaust” is, according to Jews themselves, considered the most important part of being Jewish, overriding ethnicity or even the upholding of Jewish law (!!!). Therefore, Jews in their own words agree with the assessment that they are the “eternal victim” and have a hatred of Europeans and Europeanness (“whiteness”) as a default setting. Judaism is inherently political in its desire to abolish borders and mend perceived “injustices,” and therefore all expressions of whiteness and white cultural and political power are obstacles to be overcome; barriers to the eventual completion of this grand eschatological project. “Whenever they bring down persecution on themselves (which they can’t seem to help), they rarely understand why – though they are quick to seek revenge [17],” as this response to provocation is invariably perceived by the Jews as complete racism, genocidal mania, cartoon Nazism, and psychopathy.

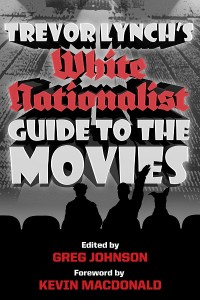

[18]

[18]You can buy Trevor Lynch’s White Nationalist Guide to the Movies here [19]

Through this, Jews believe in both a planetary egalitarianism and, paradoxically, that all whites are Nazis should they stray a mere footstep away from the path to the demographic cliff-edge marked out for them: “Revenge is something we Atlanteans understand.” Jewish revenge is of course the driver behind the anti-white murder-porn flicks Inglourious Basterds and Django Unchained. Displaying breathtaking arrogance, Jews are quite open about their desire to exterminate whites: “It was imperative to form this group,” said Nakam member Yehuda Maimon in 2016 [20], in a quote fit to be voiced on the Merchant Minute. “Heaven forbid if after the war we had just gone back to the routine without thinking about paying those bastards back. It would have been awful not to respond to those animals.” The Nakam group – literally “Revenge” or “Avengers” (Hey! That’s the name of the comic! [21]) – planned to exterminate six million Germans in the aftermath of the Second World War for the alleged crime of the Holocaust, well before the six million figure could have been verified or even guessed at beyond mere accusation. That Jews tried to murder indiscriminately is unsurprising. What is surprising is how rooted in contemporary Jewish culture the idea of revenge is, and how little whites know about it. Yehiel De-Nur’s (pen name Ka-Tsetnik [22] 135633, in reference to his time at Auschwitz) books are esteemed in Israel and are part of the Israeli high school curricula, yet his writings are not historical, but little more than lurid torture porn. In a testament to his lack of self-awareness about the falsity of hysterical accusations, De-Nur “saw himself not as a writer, but as a chronicler, a documenter.” His 1981 novel Nakam remains untranslated, so we can only make educated guesses about the revenge Jews desire to enact upon us.

In order to smuggle the mythological figure past the censors, they had to dilute Neptune and his awe-inspiring command of the ocean (a polytheistic, pagan, and Greco-Roman idea rooted in respect for nature and her primeval forces) with a Jewish neurosis. When Orm is presented to us as a villain, what is noble about him is European and what is villainous about him is Jewish: legalism, war as deceit, and a thirst for blood and revenge. They couldn’t make a watchable film by tearing down the inspirational figures of Ocean Master and Aquaman, so they had to be distorted. Surprisingly for Hollywood, family, folk, and nation are given considerable weight in the characters’ decisions throughout the movie; they are esteemed as real forces that must be carefully weighed in personal decisions: “My obligation is not to love, but to my family and my nation.” But with all this talk about “Sacred Law,” perhaps the Atlantean royals are not fully European in their thinking and have absorbed the paranoia of victimhood. Aquaman becomes a hero by taking up the cause of both the surface and subaquatic civilizations, the cause of limited conflict and mutual legitimacy: defeating the monotheistic, exclusionary Jewish cause of vengeance and endless bloodshed, “a nation for a nation.” In this, he is the “True King” of Atlan, an heir to the polytheistic cause of translation and particularism. In a waterlogged film about men holding tridents in the air and bellowing at the top of their lungs, that’s as many fathoms deep as we can ask for.