Apocalypse Now, Part 2

Posted By Fenek Solère On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,636 words

Part 2 of 3 (Part 1 here [2], Part 3 here [3])

Then he started to count. Calm and unhurried. But it was like trying to count all the trees in the forest, those arms raised high in the air, waving and shaking together, all outstretched towards the nearby shore. Scraggy branches, brown and black, quickened by a breath of hope. All bare, those fleshless Gandhi-like arms. And they rose up out of scraps of cloth, white cloth that must have been tunics once, and togas, and pilgrims’ saris. The professor reached to two hundred, then stopped. He had counted as far as he could within the bounds of the circle. Then he did a rapid calculation. Given the length and breadth of the deck, it was likely that more than thirty such circles could be laid out side by side, and that between every pair of tangent circumferences there would be two spaces, more or less triangular in shape, opposite one another, vertex to vertex, each with an area roughly equal to one third of a circle, which gives a total of 30+10+40 circles, 40×200 arms=8000 arms. Or four thousand bodies! On this one deck alone! Now, assuming that they might be several layers thick, or at least no less thick on each of the decks – and between decks and below-decks too – then the figure, astounding enough as it was, would have to be multiplied by eight. Or thirty thousand creatures on a single ship!

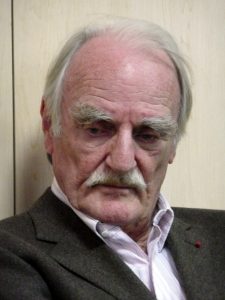

— Jean Raspail, The Camp of the Saints (1973)

These evocative images clearly convey Raspail’s dread as he penned his dystopian classic, which Time magazine described as a “bilious tirade,” the Kirkus Reviews compared to Mein Kampf, and the Southern Poverty Law Center put in the same category as The Turner Diaries. While the book is filled with foreboding regarding the future, it in fact completely underestimated the scale of the Third World invasion force that would soon roll inexorably westward.

Reality is far more frightening than fiction. Back in 1990, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reported “that the greatest single impact of climate change would be human migration.” More recently, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) predicted that two hundred million – that is one in forty-five of the world’s current population – will become climate migrants by 2050 (with 192 million already living outside their place of birth), and the UN University’s Institute for Environmental and Human Security warned that the international community had already failed in its duty to adequately prepare for the fifty million or so environmental refugees prior to 2010.

Then we have dire warnings such as those contained in Oli Brown’s Migration and Climate Change [4] report of 2008, which stated that “many areas across Southern China, South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa could become uninhabitable on a permanent basis.” Plus, the European Commission has been generously funding the Environmental Change and Forced Migration Project, comprised of multi-disciplinary teams of experts from NGOs such as the New Economics Foundation, and which insists that “all states should bear equal responsibility to deal with displaced people.”

Enter the eye-catching celebrity antics of useful idiots such as the virtuous virginal vegan Greta Thunberg, who races in her winged zero-carbon yacht across the Atlantic, while other members of her team will be flying in a gas-guzzling plane to bring the boat back to Europe. And let us not forget the revelation that eco-conscious Prince Harry and his multi-talented octoroon bride have been jetting around the globe at taxpayer expense to holiday in Ibiza and celebrate Elton John’s birthday in Nice, while the consummate hypocrite, English actress Emma Thompson, prefers to read her scripts during vapor-producing luxury transatlantic airline journeys.

Despite his prophetic gifts, Raspail could not predict the level of support the swarming hordes would receive from collaborators eager to expel indigenous Europeans from their mountains, valleys, and meadows less than half a century after his book was published. Working in tandem with the elites and perfectly exemplifying the co-dependency between climate change obsessives and refugee agencies, there are socially-conscious volunteers such as the Sea Watch Captain, Carola Rackete, who picks up migrants in the Mediterranean and takes them to Italy in a direct challenge to Italian Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini; people traffickers managing a multi-billion dollar trade between Africa and the Greek and Italian islands; Catholic priests who aid illegals in crossing the mountain routes at Bardonecchia and Ventimiglia in the Alps; Albanian Hellbanianz gangsters and Turkish crime syndicates who smuggle migrants through the Macedonian ports and into Serbia; CNN reporters and camera crews who present the Honduran caravans rolling north towards the American border as being composed of tearful children and desperate mothers rather than members of drug mafias; Democrat mayors such as Jim Kenney of Philadelphia, Libby Schaaf of Oakland, California and Jenny Durkan of Seattle, who nodded their agreement with Rahm Emanuel of Chicago when he said, “What President Trump fails to understand is that America is a sanctuary country . . . Small, medium, and large cities across the nation are suddenly and rapidly identifying as sanctuary cities because of the abandonment of Americans’ values, ideals, and cultural destiny under President Trump’s watch”; and, of course, there is the small matter of antifa gunmen attacking Immigration and Custom Enforcement (ICE) facilities in Tacoma, Washington and Aurora, Colorado.

These are all very real examples of the Pavlovian self-loathing tendency Raspail personifies in the character of “the student,” who he briefly introduces in the second chapter of his novel: “Feet bare, hair long and dirty, flowered tunic, Hindu collar, Afghan vest . . .” He is a young man who epitomizes the degeneration of the ’68 rioters in Paris, and provides a perfect parody of the psychologically warped people we see marching in the vanguard of ecological groups such as Extinction Rebellion. He is a nihilist who loots the homes of those he has lived around all his life, bragging about spitting in the face of his petit-bourgeois father when he flees before the beasts from the east make landfall and mocking his sisters for fearing that they might be raped by the newcomers. “Fantastic!” he proclaims. “I’ve been waiting for years for something like this . . . It’s great! I’m telling you, this country’s going to be something else. You won’t know it. It’s going to be born all over.”

When he is asked by a professor, “Did you see the people on the boats?”, he replies enthusiastically:

You bet I did . . . My real family is all the people coming off those boats. Here I am with a million of my brothers, and sisters, and fathers, and mothers. And wives, if I want them. I’ll sleep with the first one that lets me, and I’ll give her a baby. A nice dark baby. And after a while I’ll melt into the crowd.

The professor answers, “Yes, you’ll disappear. You’ll be lost in that mass. They won’t even know you exist.” But the student welcomes this prospect, replying:

Good! That’s just what I’m after. I’m sick of being a tool of the middle class, and I’m sick of making tools of people just like me, if that’s what you mean by existing . . . Nobody’s going to get away. Let them try to save their ass. They’re finished, all of them. Man, you should have seen it. My father, with his arms full of shoes from his store, piling them into his nice little truck. And my mother, bawling her head off, figuring out which ones to take . . . Besides everything’s mine now. And tomorrow I’m going to stand here and let them have it all. I’m like a king, man, and I’m going to give away my kingdom. Today’s Easter, right? Well, this is the last time your Christ’s going to rise . . . There’s a million Christs on those boats down there. And first thing in the morning they’re all going to rise. The millions of them . . . I got it from the priest . . . he was running like crazy down the hill. He kept stopping and lifting his arms in the air, and he’d yell out: “Thank you God, thank You!”

He goes on to say more that typifies the mindset of the people we are dealing with:

Shut up before you make me puke! Maybe you’ve got a pretty house. So what? And maybe you’re not a bad old guy. Smart and refined, and everything just right. But smug, man, so sure of your place. So sure you fit right in. With everything around you. Like this village of yours, with its twenty generations of ancestors just like you. Twenty generations without a conscience, without a heart. What a family tree! And now you are here, the last perfect branch. Because you are, you’re perfect. And that’s why I hate you. That’s why I’m going to bring them here tomorrow. The grubbiest ones in the bunch. Here, to your house. You’re nothing to them, you and all you stand for. Your world doesn’t mean a thing. They won’t even try to understand it. They’ll be tired, man. Tired and cold. And they’ll build a fire with your big wooden door. And they’ll crap all over your terrace, and wipe their hands on your shelves full of books. And they’ll spit out your wine, and eat with their fingers from all that nice pewter hanging inside on your wall. Then they’ll squat on their heels and watch your easy chairs go up in smoke. And they’ll use your fancy bed sheets to pretty themselves up in. All your things will lose meaning. Your meaning, man. What’s beautiful won’t be, what’s useful they’ll laugh at, what’s useless they won’t even bother with. Nothing’s going to be worth a thing. Except maybe a piece of string on the floor. And they’ll fight over it, and tear the whole damn place apart . . . Yes, it’s going to be tremendous! So go on, beat it. Fuck off!