Remembering Revilo Oliver (July 7, 1908–August 20, 1994)

The Professor & the Carnival Barker

Posted By

Margot Metroland

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

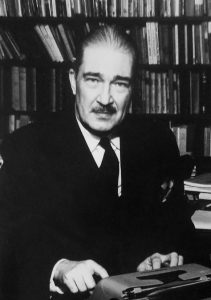

Professor Revilo Pendleton Oliver died in 1994, full of years and honors, as they say; and also notoriety. Long a Classics professor at the University of Illinois in Urbana, he gained his PhD in 1938 with a translation and commentary on a 1500-year-old Sanskrit drama. At age 80 was capable of holding lengthy telephone conversions with a young fellow linguist, in which (just to show off) they would switch back and forth between German and Attic Greek.

What made Oliver unique, however — and notorious — was his career as a cultural critic and political spokesman in the American Right, a career he maintained for decades while shouldering full academic responsibilities at the university. In the 1950s he was present at the creation of National Review and later at the founding of the John Birch Society. He eventually fell out with the founders of both organizations, partly because he grew disillusioned with their evasions and duplicity in a general sense, and partly because he urged a more frank and forthright treatment of such untouchable matters as race and the Jewish Question.

He continued to maintain cordial, if distant, relations with William Buckley and the occasional Bircher. But not so with Robert Welch, the candy tycoon who founded the John Birch Society. In seven years of association with Welch — giving speeches for his Society, editing and writing for his magazine, and generally acting as Welch’s highbrow front-man — Oliver came to regard him as nothing more than a charlatan, a swindler, a liar, and a cheat.

Prof. Oliver kept a hand in political matters, moving ever-rightward as he lent his name and oratorical persuasiveness to Lou Byers’s National Youth Alliance and then its successor, the National Alliance of Dr. William Pierce. But he never got over Robert Welch, the Master Salesman who lured him into what appeared to be an outstanding patriotic organization, then almost immediately betrayed him and the Birch Society itself.

As noted, Prof. Oliver had been a charter member of the “Birch business,” one of eleven men invited by Welch in late 1958 to the home of a wealthy, hospitable lady in Indianapolis for a two-day conference to discuss the formation of a new political movement. Another of the eleven was Koch Industries founder Fred Koch Sr. (It’s nice to imagine that the other nine were equally forceful and notorious, but this alas was not the case; their names now long consigned to Rotarian obscurity.[1] [2]) Later on such luminaries as Hollywood actors Adolphe Menjou and Walter Brennan would be part of the window-dressing of the JBS National Council, but at the start most of the Birch founders — all, in fact, except Oliver himself — were mature, wealthy businessmen, mainly from the Midwest.

Robert Welch was coward and a bad liar, something Oliver noted early on. That came in the summer of 1960. A Chicago Daily News columnist named Jack Mabley published excerpts from a private typescript that Robert Welch had circulated among his inner circle. Known simply as “The Book” (or later on, the “Black Book,” “Blue Book,” or The Politician), this was litany of political grievances that Welch wished to share with his close circle. Famously, it argued that Dwight Eisenhower had been not only been an incompetent (albeit supremely ambitious) officer during the Second World War, he was a knowing tool of the Communist Conspiracy. “The Book” was also generously sprinkled with remarks about the insidious influence of Jews in American public life and foreign relations.. [2] [3]

Robert Welch was coward and a bad liar, something Oliver noted early on. That came in the summer of 1960. A Chicago Daily News columnist named Jack Mabley published excerpts from a private typescript that Robert Welch had circulated among his inner circle. Known simply as “The Book” (or later on, the “Black Book,” “Blue Book,” or The Politician), this was litany of political grievances that Welch wished to share with his close circle. Famously, it argued that Dwight Eisenhower had been not only been an incompetent (albeit supremely ambitious) officer during the Second World War, he was a knowing tool of the Communist Conspiracy. “The Book” was also generously sprinkled with remarks about the insidious influence of Jews in American public life and foreign relations.. [2] [3]

Caught off-guard, Welch responded with a cascade of contradictory lies. He denied that the quotations were authentic; they were taken out of context; the Book was not an official prospectus, but merely a private letter, or draft, shared among some friends. After a couple of years, Welch and the Society went to the trouble of producing a sham version of the volume, with all the offending passages removed.

Prof. Oliver was faced with a dilemma. Robert Welch was clearly unworthy of his supporters, of the Society he had founded. But what to do? Oliver decided to hang on a little longer, out of loyalty to the Society’s stated goals and honest supporters. He was a major drawing-card for the John Birch Society; he couldn’t let it down. And so he did hang on a few years more, trying not to complain too vociferously when his speeches were vetted or canceled, his magazine articles censored. The end finally came in 1966, in circumstances he explains in an excerpt reproduced at bottom.

Prof. Oliver continued to publish reviews and political commentary almost until he died, age 86, at his home in Urbana. In the 1980s he regularly appeared in George Dietz’s Liberty Bell, often contributing lengthy essays that later appeared in book form. (E.g., “Enemy of Our Enemies,” his critical pendant to Yockey’s The Enemy of Europe, published in 1981.) However, he was now in his 70s and 80s, long retired from his university, and considered his public career closed.

About 1980 was persuaded to publish a collection of his favorite reviews and political commentary from the 1950s and 60s, that is to say, his National Review and American Opinion period. This compilation, America’s Decline: The Education of a “Conservative” was in due course assembled and printed in England, distributed under the invented imprint of Londonium Press.[3] [4] After a half-century or more, most of these writings hold up very well. His in-depth comparison of history-philosophers Spengler, Toynbee, Brown, et al., “History and the Historians”[4] [5] from American Opinion in 1963-64, continues to be a particularly readable and useful reference. It may be an eye-opener to anyone who doubts that highbrow academic-style criticism could have been published, serially, in the house organ of the Birch Society.

However the most trenchant parts of the book are not Oliver’s collected essays, but the autobiographical chapters that he provides as running commentary on the state of Conservatism in America. We have his early postwar hopes (riding a train with his wife, he tells her that he is confident that the Communists and scoundrels in Washington are about to be subjected to a thorough housecleaning), his early disillusionment with William Buckley and National Review, and finally the long, bitter saga with Master Salesman Robert Welch.

The book ends with a long, unsettling coda about his Birch years and American Conservatism in general. I excerpt it here at length because it both recaps the Welch story and tells, bitterly, why American social dynamics must prevent such patriotic hopes as those of the early Birchers from ever taking flight again:

With the July-August issue of 1966, my connection with American Opinion came to an end . . . The cycle begun in 1954 was completed in 1966, and I had leisure to look back on twelve years of wasted effort and of exertion for which I would never again have either the stamina or the will.

After the conference between Welch and myself in November 1965, I determined to verify conclusively the inferences that his conduct had so clearly suggested, and with the assistance of certain friends of long standing who had facilities that I lacked, I embarked on a difficult, delicate and prolonged investigation. I was not astonished, although was pained, by the discovery that Welch was merely the nominal head of the Birch business, which he operated under the supervision of a committee of Jews, while Jews also controlled the flow, through various bank accounts, of the funds that were needed to supplement the money that was extracted from the Society’s members by artfully passionate exhortations to “fight the Communists.” As soon as the investigation was complete, including the record of a seen meeting in a hotel at which Welch reported to his supervisor; I resigned from the Birch hoax on 30 July 1966 with a letter in which I let the little man know that his secret had been discovered. On the second of that month I had kept an engagement to speak at the New England Rally in Boston, where I gave the address, “Conspiracy or Degeneracy?” [5] [6] . . .

After the speech, I was warmly congratulated by Welch, who was delighted that it had been generously applauded by an audience of more than two thousand from whom he might recruit more members: he had not yet been informed by his supervisors that they disapproved. They did give him something of a dressing-down, and when I resigned, he had the idea of pretending that he had been horrified by a speech that contained racial overtones, such as well-trained Aryans must always eschew. And he had the effrontery — which he later mitigated by claiming he had not received my letter — he had the effrontery, I say, to fly to Urbana, accompanied by his lawyer and a former Director of the Federal Reserve, on the assumption that a poor professor could easily be bribed to sign a substitute letter of resignation, which he had thoughtfully written out for me, together with the article in the Birch Bulletin in which he was going to announce his surprise at receiving the letter he had written for me.

Welch’s sales-talk was perhaps a little constricted because he had always to speak with my tape recorder operating on the table between us, and since I wished to say nothing that he could later misinterpret, I resisted the temptation to feign negotiations and thus ascertain what was the very highest price he was prepared to pay for my honor and self-respect.

Since that sickening afternoon, I have been unable to think of the little shyster without revulsion and a feeling that I have been contaminated by association with him. I have tried to be not only scrupulously fair to him in the foregoing pages, but to give him the benefit of every possible doubt, and I believe I have succeeded, but it has cost me some effort . . .

I have paid almost no attention to the Birch business since I resigned. I am somewhat astonished that Welch’s superiors still think it worth the expense of supporting it, even though it does provide a playground on which innocent but perturbed Americans can run off their energies in harmless patriotic games. Friends still send me copies of some of the more remarkable verbiage that spurts from Belmont, and I note that Welch, perhaps on instructions, no longer has much to say about the “Communist Conspiracy,” and, after flirting with the notion of reactivating Weishaupt’s diabolic Illuminati, seems to have settled on the conveniently nameless and raceless “Insiders” as the architects of all evil, inspired by an unexplained malevolence. The principal purpose, aside from keeping the members in a revenue-producing excitement, is to make certain that their chaste minds are insulated against a wicked temptation not to love their enemies. The pronouncements from Belmont are of some slight interest, since one may be sure that the B’nai Birch are told only what has been approved by the B’nai B’rith . . .

It is true that today, fourteen years later [i.e., 1980] the salesmen, thanks to well-written house organs, can still sell memberships to earnest people who are worried and don’t know what to do about it, but in practical terms the Birch Society has a political importance about equal to that of the Mennonite churches, which have a much larger membership of earnest and hard-working men and women in various communities, where they may be seen driving their covered buggies on the shoulders of highways while they resolutely hold to their faith and avert their eyes from all the works of the Devil . . .

The Birch Society was essentially an effort by the Aryans of the middle class. My pleasantest memories connected with it are of my gracious hosts, the members of local chapters in various cities throughout the nation who sponsored my lectures on its behalf. The men and women whom I thus met were the finest type of Americans, and I enjoyed the afternoons and evenings I spent in their company, but they were all (so far as I could tell) members of our race. But almost without exception, those intelligent and amiable men and women had failed to draw the obvious deduction from that fact — failed to regard the racial bond that was the one thing they all had in common, for the managers of the Birch business had actually endorsed the poisonous propaganda that teaches Aryans that they are the one race that has no right to respect itself or even be conscious of its identity . . .

Membership in the middle class, however, always implied a certain measure of economic independence, and the loss of that independence dissolved the middle class as a significant social stratum.

The scheme of organization of the Birch Society called for chapters that were to meet in informal rotation in the homes of the members. That presupposed fairly spacious homes, incomes adequate to maintain them, hostesses who had some leisure for social activities and could obtain, at least occasionally, some domestic help, and, usually, men who had secretaries whose services they could divert from time to time. So long as the members were to be of the class that supplies “community leaders” and were to be the organizers of local “fronts,” that scheme of organization was unexceptionable and indeed requisite, and such prestige as the Society ever had depended on the rule, ‘The Birch Society always travels first class’. When the Birch business tried to become in itself a popular movement, the chapter organization made it almost impossible to enlist any substantial support from the “working class.” A member who received hospitality he could not return was necessarily embarrassed, and segregation of members into chapters on the basis of income merely accentuated economic differences.

The Birch salesmen soon began to vend their gospel to anyone who could be induced to pay the comparatively low dues; indeed, they had to, to meet their implied sales-quotas. The increasingly proletarian structure of American society did not alleviate the inherent difficulties, for there remains the divergence of interest between “management” and “labor,” and, as in all the societies infested by Jews, there is a reciprocal hostility that is always latent and is evoked by talk about “free enterprise” and the other socioeconomic principles that were traditionally esteemed as virtues by the middle class. The only conceivable basis for a political movement that could transcend differences in income and manners is, of course, the biological unity of race — and that, of course, is precisely what the Birch hoax is now used to prevent enemies, both sophisticated and savage, while toiling to subsidize them. Many of those estimable persons would have been shocked by a suggestion that they had a right to consider first their own welfare and that of their children, for that would have been “selfish” and even sceptics have been imbued with the hoary Christian hokum that we must love those who hate us. There was, therefore, no feasible course of action in 1966, when I knew that those well-meaning Aryans had been betrayed and I felt certain that their cause had been irretrievably lost—although I tried to hope that my estimate was somehow wrong.

The American middle class has now been liquidated, except for a few remnants that are found here and there and are tolerated because they have no vestige of political power and will soon disappear anyway. A middle class can be based only on property — on the secure possession of real property of which a man can be divested only by his own folly. A middle class cannot be formed of comparatively well-paid proletarians who may have a theoretical equity in a hundred-and-fifty-thousand-dollar house they are “buying” on a thirty-five year mortgage, and in a fifteen-thousand-dollar automobile for which they will not have paid before they “trade it in” on a more expensive and defective vehicle. Nor can it be formed of proletarians whose wives have to work — whether as “executives” or as charwomen — to “make ends meet.” With the exception of relicts who live on investments that have not yet been entireIy confiscated by taxation, the economic revolution is as complete in the United States as in Soviet Russia: there are only proletarians, some of whom are hired to manage the rest. Managerial employees get more pay and ulcers than janitors and coal miners, but they are equally dependent on their wages and even more dependent on the favor of the employee above them. The nearest approximation to a middle class, both here and in Russia, is the bureaucracy, and it is their vested interest that the Birchers imagine they can destroy.

The poor Birchers go on playing patriotic games on their well-fenced playground. They pay their dues and buy books and pamphlets from Belmont to distribute to persons who may read the printed paper before discarding it. They continue, now and then, to coax a few friends to hear an approved speaker, who, if not a Jew himself, at least knows who his bosses are, and they all listen excitedly as he tells them how very bad everything is, from Washington to Timbuctoo, without ever mentioning any of the nasty facts of race and genetics, about which nice boys and girls should never think . . .

The B’nai Birch, to be sure, may bask in the approval of their amused and contemptuous Jewish supervisors, and they may feel some satisfaction that they keep their minds so pure and moral that they hate the wicked “racists” who believe, rightly or wrongly, that our race is fit to live, and who have the one cause that might conceivably generate sufficient political power to preserve us from the ignominious end of cowards fit only for slavery and a squalid death. But even in this respect the Birch hoax, now so insignificant that the prostitutes of the press forget to say unkind things about it now and then to make the members feel important, has become so impotent that it will not measurably affect our fate, whatever that is to be.

So long as it was honest (if it ever was), the Birch Society represented the last hope of American Conservatism, of the effort to restore the values and the freedom of the way of life of our Aryan forefathers on this continent — to regain what they lost when they thoughtlessly permitted their country to be invaded, their government to be captured, and their society to be systematically debauched and polluted by whining aliens. The American tradition was a fair and indeed noble one, and it still has the power to awaken nostalgia for a world that no man living has himself experienced, but for practical purposes, it now has only a literary and historical significance. To be sure, there are, outside the inconsequential Birch playpens, earnest men and women who still hope to restore the decent society and strictly limited government of that tradition, and their loyalty to what has ineluctably passed away entitles them to respect, just as we respect the British Jacobites, who remained loyal to the Stuarts and nourished hopes for a century after Culloden, and as we respect the earnest men and women in France who, as late as 1940, remained loyal to the Bourbons and dreamed of restoring them to their throne. But such nostalgic aspirations for the past are mere romanticism. They are dangerously antiquarian illusions today, when the only really fundamental question is whether our race still has the will-to-live or is so biologically degenerate that it will choose extinction—to be absorbed in a pullulant and pestilential mass of mindless mongrels, while the triumphant Jews keep their holy race pure and predatory.

American Conservatism is finished, and its remaining adherents are, whether they know it or not, merely ghosts wandering, mazed, in the daylight. And it is at this point that the present volume of selections from what I wrote on behalf of a lost cause fittingly ends.[6] [7]

Notes

[1] Those eleven men who attended Welch’s Indianapolis meeting in 1958, including the two who declined to put their names on the original National Council (Kent, Scott) were: [8]T. Coleman Andrews (Richmond VA); Laurence E. Bunker (Wellesley Hills MA); William J. Grede (Milwaukee WI); William R. Kent (Memphis TN); Fred C. Koch (Wichita KS); W.B. McMillan (St. Louis, MO); Revilo P. Oliver (Urbana IL); Louis Ruthenburg (Evansville IN); Fitzhugh Scott, Jr. (Milwaukee WI); Robert W. Stoddard (Worcester MA); Ernest W. Swigert (Portland OR). Listed here [9].

[2] [10] Revilo Oliver, America’s Decline, 1981, reprinted 2006.

[3] [11] Londonium Press’s address in the original edition was 21 Kensington Park Road, which now houses a bookshop but was in those days the home and storeroom of Bill Hopkins — antiques dealer, novelist, and notorious “Angry Young Man” of the 1950s.

[4] [12] Oliver, America’s Decline, pp. 228 et seq.)

[5] [13] Audio of the speech on YouTube [14].

[6] [15] Oliver, “Aftermath,” America’s Decline, pp. 421 et seq.