“Now it’s dark . . .”

David Lynch’s Blue Velvet

Posted By

Trevor Lynch

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

Jeffrey: I’m seeing something that was always hidden. I’m involved in a mystery. And it’s all secret.

Sandy: You like mysteries that much?

Jeffrey: Yeah. You’re a mystery. I like you. Very much.

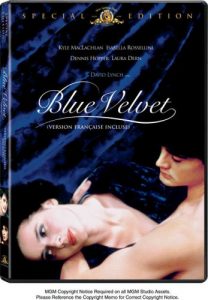

Blue Velvet (1986) is the quintessential David Lynch film, filled with quirky humor and shocking violence. It features one of the most terrifying villains in all of film: Frank Booth, brilliantly portrayed by Dennis Hopper. Blue Velvet is a “mystery” story. But it is more than just a crime drama. Sometimes it is described as neo noir. But it is a much darker shade of noir.

Blue Velvet is about the great mysteries of life. It is a coming-of-age tale about callow college-boy Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLaughlin) becoming a man. It is also an initiation tale, with sexual, spiritual, and political dimensions. A good mystery can be engaging, but superficial. Blue Velvet is powerful and moving because its archetypal, religious, and philosophical themes stir deeper parts of the soul.

Jeffrey’s initiation into the mysteries is a descent into the underworld: both a literal, criminal underworld as well as the “deep river” of the unconscious, including obsessive and sadomasochistic sexuality. But Lynch also hints that the unconscious is not merely human, but a portal through which essentially demonic powers enter our world.

Jeffrey conquers and controls these forces, returning to the sunlit world not only as a man but as a guardian of the social and the family order. In his journey, he has encountered the libidinal, criminal, and demonic forces that can tear society apart, and he has learned about the artifices of civilization that keep chaos at bay. Politically speaking, this is a profoundly conservative vision.

After the nocturnal opening titles, with their elegant script, shimmering blue-velvet backdrop, and lush, Italianate theme music by Angelo Badalamenti, the famous opening sequence sets up the whole story. To Bobby Vinton’s oldie “Blue Velvet,” we see a clear blue sky, then our eyes descend to red roses in front of the archetypal white picket fence. An old-fashioned firetruck drives by, complete with dalmatian, a fireman benevolently waving from the running board, a gesture that subtly puts the viewer in the position of a child. Then we see yellow tulips. A crossing guard carefully shepherds little girls across the street.

It is a vision of childlike wholesomeness and safety. Indeed, all the adults are people charged with keeping the public safe. The guardians of public safety are an important theme in Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks.

Then we see the modest Beaumont house. Mr. Beaumont is watering the yard. Mrs. Beaumont is watching a crime drama on TV—the first hint of darkness—although the gun on the screen usually elicits a laugh, and it is all tidily contained on the tube. Then we hear an amplified gurgling and see Mr. Beaumont’s hose snagged and kinked on a branch. As he yanks the hose, he is suddenly stricken and falls to the ground, water geysering everywhere. Then we see him on his back, a baby in diapers watching as a terrier seems to attack the water squirting from the hose. The film slows, giving the dog both maniacal and mechanical qualities. Then we dive into the well-watered lawn, down to the roots, where in the darkness we find a writhing mass of beetles and other insects fighting and devouring one another.

Next we hear a corny radio jingle, which welcomes us to Lumberton, an idyllic North Carolina logging town, the model for the titular town in Twin Peaks, Lynch’s next project.

Young Jeffrey Beaumont has been called home from college to visit his stricken father and help run the family hardware store. On the way home from the hospital, Jeffrey discovers a severed human ear in a field. It has greenish splotches of decay on it, and it is crawling with bugs. Bugs, again, are associated with evil.

Jeffrey puts the ear in a paper bag and takes it to Detective Williams (George Dickerson) at the Lumberton Police Department. Detective Williams immediately begins an investigation. He and Jeffrey first take the ear to the morgue, where the medical examiner observes that it had been cut off with scissors. Then they go to the field to search for evidence.

Cut to later that evening. A door opens, and light descends into a darkened stairwell. Jeffrey descends into the darkness as well. His journey into the underworld has begun. He tells his mother (Priscilla Pointer) and fretful aunt Barbara (Frances Bay) that he is going out walking. “You’re not going down by Lincoln, are you?” asks aunt Barbara fearfully. Jeffrey says no. It seems a silly prejudice, but later we realize that it was well-founded. Bad things happen down by Lincoln. (Odd that Lynch chose that name, associated with a President unpopular in North Carolina.)

As Jeffrey walks the neighborhood, we cut to a closeup of the ear in the morgue. There is a loud humming as we enter the ear, then everything fades to black. This too is a descent into mystery, into the underworld.

Cut to Jeffrey knocking at the door of the Williams house. Jeffrey wants to know more about the ear, but Detective Williams can’t tell him, and asks him not to disclose anything he already knows, until the case is concluded. Detective Williams is stern but warm, a surrogate for Jeffrey’s stricken father. He tells Jeffrey that he understands his curiosity. It is what got him into police work in the first place. “It must be great,” Jeffrey volunteers. “It’s horrible too,” he replies. But Jeffrey seems undaunted. He is on a path that may lead him to becoming a guardian of public order, someone who exposes himself to evil, risking his life to serve the common good.

When Jeffrey leaves the Williams house, he hears a voice: “Are you the one that found the ear?” He looks into the darkness. Detective Williams’ daughter Sandy (Laura Dern) emerges from the night, a pink-clad blonde vision of loveliness. She is coy and mysterious, teasing Jeffrey with her knowledge of the case.

As they walk together, she tells him that she overheard her father talking. The ear may somehow be connected to the case of Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini), a singer who lives nearby. Sandy leads Jeffrey to Dorothy’s apartment building. With a slightly comic/ominous music cue, the camera pans up to the sign: Lincoln St.

The next afternoon, Jeffrey picks Sandy up after school. They go to Arlene’s, a diner that is the prototype of the RR in Twin Peaks, right down to the passing logging truck. Jeffrey then tries to involve Sandy in a scheme. He wants to look around Dorothy Vallens’ apartment. He will pretend that he is the pest control man, there to spray for bugs (which are of course already associated with darkness and evil). Sandy will pretend to be Jehovah’s witness, with copies of Awake! magazine, who will draw Dorothy away, allowing Jeffrey to open one of the windows for a later visit. (There is an interesting Manichean polarity in their covers, mirrored in Jeffrey’s near black and Sandy’s golden blonde hair.)

How Jeffrey plans to get in a seventh-floor window is not explained, but he hasn’t really thought it out. He doesn’t even know Dorothy’s name or apartment number without Sandy’s help. When we arrive, we see that Dorothy lives in the Deep River Apartments, a nomen that may also be an omen of Jeffrey getting in way over his head. (Betty Elms, in Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, hails from Deep River, Ontario.)

Dorothy’s apartment is pure Lynch: retro, slightly dingy, with dusky pink walls and carpets, dark red draperies (shades of Twin Peaks), lavender sofas, magenta cushions, and putrid green accents in the form of pots with spiky “mother in law’s tongue” plants. The warm colors have a womblike feel, but the overall effect is seedy and sluttish, not maternal. Jeffrey does not manage to find a window, and before Sandy can knock, Dorothy is visited by a glowering man in a bright yellow sport jacket. But he does manage to pocket an extra pair of keys, hoping they will unlock the apartment.

That evening, Jeffrey takes Sandy to dinner at The Slow Club to watch Dorothy Vallens sing. She doesn’t have much of a voice, but she still makes a captivating spectacle, with her huge retro microphone and blue-lit band against dark red draperies, more foreshadowing of Twin Peaks. Then Jeffrey and Sandy return to Dorothy’s apartment. When Sandy says goodbye, she tells him, “I don’t know if you’re a detective or a pervert.” Jeffrey sneaks inside. When Dorothy comes home suddenly, Jeffrey hides in the closet. Peering through the slats, he watches her undress. It turns out he’s both a detective and a pervert.

Dorothy hears a rustling in her closet and confronts Jeffrey with a knife, jabbing him in the cheek when he does not answer one of her questions. She thinks he is a voyeur. But instead of calling the police, she orders him to undress. Then she kneels, with a worshipful look on her face, and pulls down his boxer shorts. She kisses and caresses him but also threatens to kill him, demanding that he neither look at nor touch her. Then she asks if he likes that kind of talk. He doesn’t. She tells him to lie down on a couch, following him knife held high like a stage actress. Then she gets on top of him, knife poised, and kisses him.

Terrified by a loud pounding on the door, Dorothy hustles Jeffrey into the closet and orders him to stay silent. Jeffrey is the voyeur again, poised to witness one of the weirdest and sickest scenes in all of cinema. Enter Frank Booth, a middle-aged man in a leather jacket and rockabilly shirt, seething with unfocused rage. Frank and Dorothy then role-play a sexual scenario not unlike the one that has just transpired with Jeffrey, although this time Frank is in control.

Frank’s scenario is very specific. Dorothy has to wear a blue velvet robe, provide him with a glass of bourbon, dim the lights and light a candle (“Now it’s dark,” he says), and sit on a particular chair. He demands that Dorothy not look at him and punches her savagely when she does. (She looks at least three times.) Loosening his inhibitions by swigging the bourbon, then huffing some sort of gas from a cylinder under his jacket, he refers to her as “mommy” and himself as “baby” and “daddy.”

He begins by viewing her vagina, then pinching her breasts, then, red-faced and maniacal, he hurls her to the floor, threatens her with a pair of scissors, then pantomimes intercourse, yelling “Daddy’s coming home, daddy’s coming home.”

He has a fetishistic attachment to her blue velvet bathrobe. She stuffs it in his mouth, he stuffs it in her mouth, and he even carries around a piece of it that he has cut from the hem, perhaps with the scissors he uses to threaten her. When it is all over, he blows out the candle. “Now it’s dark,” he repeats.

As Jeffrey later says, “Frank is a very sick and dangerous man.” A drug dealer, he has kidnapped Dorothy’s husband Don and their small boy, Donny, holding them hostage to force Dorothy into sexual bondage. It is Don’s ear that Jeffrey found, cut off as a threat to Dorothy, perhaps with the same scissors with which he menaced her. Frank has removed Dorothy’s real baby and daddy so he can have “mommy” all to himself.

But Dorothy’s own disturbing behavior makes it hard to view her as simply a victim. When Frank screams, “Don’t you fucking look at me” and punches Dorothy, her head lolls back with an ecstatic smile on her face. When she looks at him again and again, is she asking for it? She herself has forced Jeffrey to strip at knife-point, ordering him not to look at or touch her while she looks at and touches him. One way to make someone into an object is to forbid them from being a subject.

When Frank leaves, Jeffrey creeps out of the closet to comfort Dorothy, who first claims she is all right. Then she asks Jeffrey to hold her, referring to him as her husband Don. Either she is delirious or simply playing a role. The latter seems more likely, for without missing a beat, she begins to seduce Jeffrey, asking him to look at her, then touch her . . . then hit her. Now she’s literally asking for it.

A feminist would automatically claim that Dorothy has been so traumatized by Frank that she is simply reenacting her trauma with Jeffrey. But another possibility suggests itself. Dorothy is very much in control with Jeffrey. She is not so worried about Frank or her husband and son that she cannot start an affair with a new man.

It is interesting that when Jeffrey tells Dorothy that he knows what has happened to her husband and son, she is impassive. She only reacts when he suggests telling the police, and she uses her reaction to finally goad Jeffrey into hitting her.

This awakens something in both of them, represented by a burst of flames bringing to mind similar effects in Lynch’s next movie, Wild at Heart [2], as well as slowing down the film and replacing the sound of their lovemaking by distorted animal shrieks and growls. This is Jeffrey’s baptism in the deep river of repressed animal sexuality. Jeffrey is in way over his head, but Dorothy is in firm control.

Did Frank undergo a similar initiation? Was the kidnapping his way of seeking somehow to regain a semblance of control in the throes of an obsession?

Now it’s really dark.

There are a number of clues that point to Frank’s deep sexual abjection. As the “baby” he can pinch Dorothy’s breasts. But as “daddy” he merely pantomimes intercourse. Frank may actually be impotent. At least he is with Dorothy.

When Jeffrey returns to The Slow Club, he sees Frank in the audience, fondling his blue velvet fetish, deeply moved by Dorothy’s performance, almost at the edge of tears.

The night Dorothy goads Jeffrey into hitting her, he bumps into Frank and his gang as he leaves her apartment. Frank flies into a jealous rage, forcing Jeffrey and Dorothy to go on a “joy ride.” At their first stop, Frank says: “This. Is. It.” And sure enough, a red neon sign reads: “This Is It.”

But it is hard to say what “it” is. It seems like a retirement home for old fat whores. The interior color scheme is very much like Dorothy’s apartment. It is littered with beer and prescription bottles and presided over by a flamboyant aging homosexual named Ben, hilariously played by Dean Stockwell, all pursed lips and rolling eyes. Ben is involved with Frank’s drug trade and is holding Dorothy’s husband and son hostage.

Frank goes on and on about how “suave” Ben is, with his smoking jacket, ruffled shirt, and long cigarette holder. Every other word is “fuck.” When Ben proposes a toast to Frank’s health, he hilariously rejects it, suggesting “Here’s to your fuck” instead. After transacting some drug business, Frank asks Ben to lip-sync to Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams,” which Frank childishly refers to as “Candy-colored clown,” a phrase in the first line of the song.

Ben switches on an inspection light, which he uses as a fake microphone, giving his powdered face a ghastly pallor. One gets the feeling that Ben has done this kind of thing before in a thousand drag shows. When we get to the words, “In dreams you’re mine, all the time,” Frank’s face becomes agitated, and Ben fearfully cuts short the mime. Frank shuts off the tape, Ben shuts off the light, and Frank says, “Now it’s dark.” Then they make to leave, Frank’s departing words: “Let’s fuck. I’ll fuck anything that moves!”

Next stop is a sawmill near Meadow Lane. Frank begins huffing his gas, then tells Jeffrey, “You’re like me.” Thanks to Dorothy, that’s now truer than Jeffrey would like to think. Then Frank begins to pinch Dorothy’s breasts, hurting her. Jeffrey tells Frank “Leave her alone,” then punches him in the face. He’s already slapped Dorothy around that evening. He’s getting comfortable with this.

Frank flies into absolute fury. His henchmen drag Jeffrey out of the car and hold him. There’s an ominous industrial thrumming and thumping in the background, as in Eraserhead. Frank puts on Dorothy’s lipstick, then kisses Jeffrey all over his face, saying “pretty, pretty,” huffing more fumes, and threatening to kill him he sees Dorothy again.

While “In Dreams” plays in the car and one of Ben’s vacant whores dances on the roof, Frank repeats the words, “In dreams, I walk with you. In dreams, I talk to you. In dreams you’re mine, all the time. We’re together in dreams, in dreams,” adding the words “forever in dreams.” He places a hand to Jeffrey’s ear and “lip-syncs” the words like it is a sock puppet. One thing is for sure: Frank is going to haunt Jeffrey’s dreams for the rest of his life. Frank is putting his disease in him.

Frank caresses Jeffrey’s face with his blue velvet fetish, wiping off the lipstick. Flexing his biceps, he tells Jeffrey to feel them. “You like that? You like that?” Then Frank begins beating Jeffrey senseless while Dorothy screams. Cut to a guttering candle. And now it’s dark.

Frank’s constant talk of fucking, as well as merely pantomiming the act with Dorothy, suggest he is impotent. The song “In Dreams” is also about unrequited love for someone who can be possessed only in dreams, itself very close to sexual impotence. Frank’s repeated compliments to Ben, as well as the lipstick, kisses, and “feel my muscles” routine with Jeffrey, strongly suggest latent homosexuality.

The guy is a mess.

Jeffrey recovers consciousness in the morning. In addition to the pain of the beating, he feels pangs of guilt as well, for he too has tasted the pleasures of sadism. In some way, he really is like Frank.

Jeffrey resolves to go to Detective Williams at the police station but discovers that Williams’ partner, Detective Gordon, is the “yellow man,” one of Frank’s partners in crime. That evening, we see Jeffrey emerge from the dark carrying an envelope, suggesting his return from the underworld. He shares his findings with Detective Williams, who begins plotting to take down Frank and his gang.

A couple days pass. It is Friday. Jeffrey waters the lawn, visits his dad, then picks up Sandy to go to a party. They are now officially dating. After the party, they are followed by a menacing car. They think it is Frank, but when the car pulls alongside, Sandy sees that it is her jealous ex-boyfriend Mike. When they pull up to the Beaumont house, Mike threatens to beat up Jeffrey, but then Dorothy Vallens staggers out of the dark, beaten and bloody. Mike stammers out an apology, and Jeffrey and Sandy take Dorothy to the Williams house to call an ambulance.

Sandy cringes in horror as Dorothy calls Jeffrey her “secret lover” and repeats, “He put his disease in me.” In truth, Dorothy is the one who put her sadomasochistic disease in Jeffrey.

After Dorothy is taken to the hospital, Jeffrey goes to her apartment and finds evidence of Frank’s fury. Dorothy’s husband Don is dead, his brains blown out, Frank’s strip of blue velvet stuffed in his mouth. The yellow man is standing in the middle of the room in shock, a huge hole blown in the side of his head, brain matter visible. Over the yellow man’s police radio, Jeffrey hears that the raid on Frank’s apartment has commenced. As Jeffrey leaves, however, he sees Frank approaching the apartment. He rushes back inside, calls for help on the police radio, grabs the yellow man’s gun, and hides in the closet.

Frank, who has heard the call on his police radio, bursts into the apartment. Yanking his swatch of blue velvet from Don’s mouth and draping it over the silencer of his pistol, then huffing his mysterious fumes, he searches for Jeffrey in the bedrooms, calling out “Here pretty, pretty” like he is summoning a dog. Returning to the living room, he silences the TV and topples the yellow man with bullets, then realizes Jeffrey is in the closet. Huffing more fumes, he ecstatically closes in for the kill, but Jeffrey sees him coming through the slats and shoots him in the head. The voyeur has become an actor.

The slow-motion headshot is accompanied by a terrifying simian shrieking. The bulbs in the floor lamp then surge with electricity and burn out, as if Frank’s life force is fleeing through the wiring. In the visual code established in Eraserhead this signifies the presence of the supernatural, especially the demonic. Frank is somehow both more and less than human.

There is a strong spiritual-religious element to Blue Velvet, as with all of Lynch’s work. Although Lynch himself is a practitioner of Transcendental Meditation, which makes him a Hindu of sorts, the spiritual imagery of his movies tends to be Western, primarily Christian but also Gnostic. I read Eraserhead, for instance, as a Gnostic anti-sex film [3]. Like Eraserhead, Blue Velvet treats sex as a form of bondage to subhuman powers, both animal and demonic. But Blue Velvet is far less nihilistic than Eraserhead. The demonic forces are balanced out by angelic ones, represented by robins and light from above, as opposed to electric light, which for Lynch has demonic connotations.

The night after his first terrifying encounter with Frank, Jeffrey tells Sandy what he has seen. Sandy picks him up in her car, an odd role reversal putting her in the driver’s seat. She parks near a church with colorful stained-glass windows, brightly lit from inside. Organ music plays in the background.

Jeffrey prefaces the story of Frank and Dorothy with the words, “It’s a strange world,” which becomes something of a Leitmotif in the film. After telling Sandy who Frank is and what he has done, Jeffrey asks, “Why are there people like Frank? Why is there so much trouble in this world?” His face is anguished and childlike, for he is just discovering the darkness of the adult world. Jeffrey’s question is not merely psychological. Given the backdrop of church and organ music, it is also theological. It is the problem of evil: If God is perfect in his power and goodness, why are there people like Frank? What is there so much trouble in this world?

Sandy says she doesn’t know the answer. But she does in a way. For she tells Jeffrey of the dream she had the night they met:

In the dream, there was our world, and the world was dark, because there weren’t any robins. And the robins represented love. And for the longest time, there was just this darkness. And all of a sudden, thousands of robins were set free, and they flew down and brought this blinding light of love. And it seemed like that love would be the only thing that would make any difference. And it did. So I guess it means, there is trouble till the robins come.

As Sandy speaks of the blinding light of love, one realizes the organ music is not coming from the church. It is part of the score, underscoring the essentially religious nature of her dream. Love, light from above, and robins are the forces that will beat back hate, darkness, and bugs. Evil is only temporary, until the robins come. Sandy has essentially delivered a religious sermon, sitting in the driver’s seat.

After Jeffrey’s first encounter with Frank and Dorothy, we see him on the sidewalk. He emerges from darkness. Then he freezes as a light comes from above. Is this the light of judgment? Then we see distorted images of Jeffrey’s father in the hospital, then Frank raving, then the guttering candle, then Dorothy saying, “Hit me.” We then see Frank punch at the camera. Is he hitting Dorothy or Jeffrey at this point? Jeffrey then awakens from a nightmare.

After Jeffrey kills Frank, Sandy, her father, and a legion of police and paramedics arrive on the scene. Even though Jeffrey has rescued himself, we only really breathe again when we see the flashing lights and guardians of order. In the middle of the bustling crime scene, Jeffrey and Sandy embrace and kiss, bathed in white light from above. There is trouble till the robins come.

Cut to an extreme closeup of an ear. Near the beginning of the story, we were drawn into the mystery by entering the dead ear to ominous industrial noise. Now we are at the end of the story, the mystery solved, emerging from a pink and living ear to Julee Cruise’s ethereal “Mysteries of Love” (yet another foreshadowing of Twin Peaks).

As the camera pulls back, we see that the ear belongs to Jeffrey, sleeping in the sunshine. He opens his eyes and sees a robin perched in a tree. Sandy calls out, “Jeffrey, lunch is ready.” Mr. Beaumont is out of the hospital, up on his feet, working on something in the yard with Detective Williams. Jeffrey’s mother and Mrs. Williams are chatting together in the living room. The families have come together. It is a sign that Jeffrey and Sandy have a serious relationship. Perhaps marriage is in the future.

Aunt Barbara and Sandy are preparing lunch in the kitchen when the robin appears on the windowsill with a bug squirming in its beak. The forces of good have quelled the forces of evil. “Maybe the robins are here,” says Jeffrey.

“I don’t see how they could do that. I could never eat a bug,” volunteers aunt Barbara, before stuffing something that looks vaguely bug-like in her mouth. Aunt Barbara is a robin without even knowing it. Thus Blue Velvet vindicates all guardians of public order, even the silliest and least self-conscious form, namely prejudice: “You’re not going down by Lincoln, are you?”

“It’s a strange world, isn’t it?” observes Sandy.

Then we see the yellow tulips, the friendly fireman, and the red roses. But before we return to the blue sky, we see Dorothy Vallens and her little boy in a park. She picks him up and holds him, smiling, although her face then takes on a sad and haunted look.

It is the happiest ending possible after such a hellish journey.

What is the political philosophy of Blue Velvet? I read Lynch as fundamentally conservative. The typical sneering Leftist take on Lynch’s opening is that the idyllic surface of Lumberton is fake and kitschy, whereas the truth about Lumberton is the bloody struggle of vermin in the dark. But Lynch’s own view is far more nuanced.

Lynch knows that civilization is artificial, a construct, a triumph over nature. But Lynch is not a liberal or a Leftist because he does not think that nature is good. Thus he does not conclude that the conventions that constrain nature are bad. Lynch thinks that nature is profoundly dangerous, especially sex and sadism, which for him have a supernatural, demonic quality. Lynch does not believe in the “natural goodness” of man. He believes in the natural—and supernatural—badness of man. Which means that human nature needs to be constrained by human conventions.

Frank Booth is Lynch’s portrait of what you get when nature is liberated by the breakdown of social repressions. The French Revolution ended with the Terror. The Sixties ethic of sex, drugs, and rock-and-roll didn’t lead us back to the Garden of Eden. It gave us the Tate-LaBianca murders, the Weathermen, and Frank Booth.

Frank is not just a sex maniac. He is a drug dealer. His partner in crime, Ben, sells both sex and drugs. Frank uses alcohol and also his mysterious gas to break down his inhibitions and release his sadism. Moreover, Frank always has his Roy Orbison soundtrack tape handy. Finally, to channel F. Roger Devlin for a moment, Dorothy Vallens can also be seen as an example of the havoc created by female narcissism, masochism, and hypergamy when social conventions break down.

Sade knew human nature better than Rousseau.

Many viewers note that the robin at the end is clearly fake, some sort of puppet. It might simply have been the best effect that Lynch could create with the available budget. But it could very well have been intentional. The bugs represent hate and evil, whereas the robins represent love and goodness. The bugs are darkness; the robins are light. If the bugs represent nature, then the robins have to represent something other than nature. In Sandy’s dream, they clearly have a supernatural aspect.

But another opposite of nature is convention, in which case it makes sense to have an obviously artificial robin. The robin represents the conventions that hold the savagery of nature in check, including the guardians of public order: the police, firemen, paramedics, even the crossing guards. These conventions also include moral principles, manners, and even Aunt Barbara’s prejudices.

Although Blue Velvet was Lynch’s fourth feature film, it was really the first where he had both creative control and an adequate budget. (Well, maybe not for the robin.) The Elephant Man (1980) and Dune (1984) gave Lynch adequate funding, but no creative control. Eraserhead (1977) was entirely Lynch’s baby, but he created it over a period of years on a shoestring budget. It is a measure of Lynch’s genius that the very first time he had the financial and creative freedom to fully realize his vision, he created what is arguably his greatest film. Certainly it is his most Lynchian.

Source: http://www.unz.com/tlynch/now-its-dark/ [4]