Cabaret

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled1,886 words

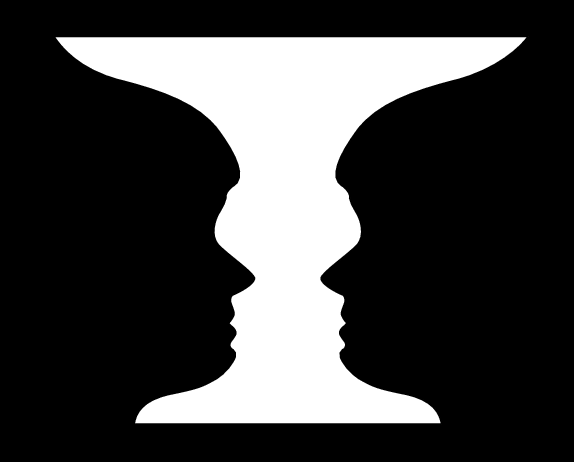

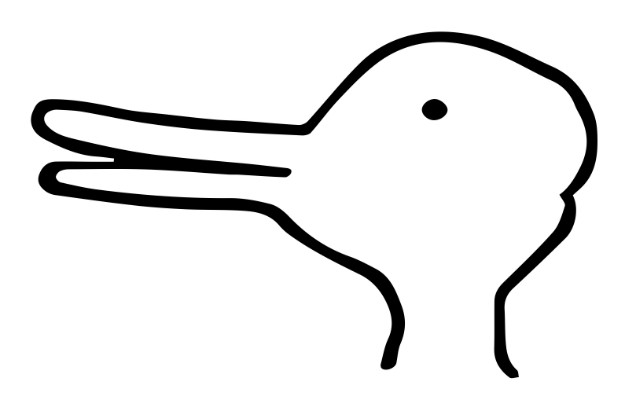

Bob Fosse’s 1972 film Cabaret is supposed to be propaganda for Weimar decadence and against Nazi brutality. But the film utterly fails as propaganda insofar as it changes no minds. In fact, Cabaret is more akin to a diagnostic tool—like inkblot tests or gestalt images—for distinguishing between fundamentally different human types: people who love beauty versus people who love ugliness, people who love order versus people who love chaos, people who love health versus people who love decadence.

Just as some see a goblet and others a pair of profiles, just as some see a duck and others a rabbit, some see Cabaret as a celebration of decadence and others see it as a case for National Socialism. Most of the latter, of course, do not embrace or condone National Socialism themselves. But once the movie is over, they can at least understand why millions of Germans did so.

This is why I include Cabaret in my pantheon of Goebbels Award laureates—namely Hollywood films that Joseph Goebbels would have released unaltered—including such titles as Quiz Show, Storytelling, Miller’s Crossing, and Barton Fink.

[3]Cabaret is set in Berlin in the early 1930s, just before the Nazis came to power. The titular cabaret is the Kit Kat Klub, which is upheld as the epitome of Weimar culture, as indeed it is. But what do we see on stage? Is it a new image of man’s highest potential? Is it a vision of a perfected society? Nothing of the sort. It is merely a parody and inversion of the existing culture and its values, including its sexual mores, martial ethos, and aesthetic standards.

[3]Cabaret is set in Berlin in the early 1930s, just before the Nazis came to power. The titular cabaret is the Kit Kat Klub, which is upheld as the epitome of Weimar culture, as indeed it is. But what do we see on stage? Is it a new image of man’s highest potential? Is it a vision of a perfected society? Nothing of the sort. It is merely a parody and inversion of the existing culture and its values, including its sexual mores, martial ethos, and aesthetic standards.

The music is jazz of the most irritating type: brassy tuneless farts and raspberries over a monotonous, herky-jerky beat. The singing is tuneless and brassy Broadway caterwauling. The musicians are ugly women and female impersonators with exaggerated and grotesque clown makeup and skimpy costumes revealing sagging, ravaged flesh. The MC, played by Joel Grey (born Joel David Katz), is leering and sexually ambiguous, with ghastly yellow teeth.

The stage shows include ugly women wrestling in mud, bondage and sadism set to music, a bawdy burlesque in which dancers in German folk costumes slap one another’s asses, females and female impersonators mocking soldiers, a song about a ménage à trois, and a song about miscegenation, in which the singer pledges his love to a gorilla but ends with the words, “But she doesn’t look Jewish at all.” It is pure cultural Bolshevism from start to finish.

The main character of Cabaret is Sally Bowles, a singer and aspiring actress. Sally Bowles was English in Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin Stories, the Ur-text of this and other adaptations. But in Cabaret, she is an American because, well, Liza Minnelli couldn’t play her as anything else. I have not read Isherwood’s original, so I can’t tell if Miss Minnelli does his character justice. Let’s just say that if Sally Bowles is meant to be a mediocre singer with a potato face and potato physique, such that her aspirations to be a great actress are a pathetic delusion, then Minnelli nails the part. Her attempts at glamor are laughable: an unfeminine bowl-cut, clown makeup, and gaudy thrift store rags, to say nothing of her braying speech, gawky mannerisms, and mannish gait. When we first see her on stage, she looks like a cartoon mouse pretending to be a dominatrix.

Sally’s motto is “divine decadence,” although it may simply be a brand of nail polish. Her philosophy is pure hedonism. Anything goes, “as long as you’re having fun.” She smokes, drinks, and fornicates with abandon. Her goal is to become a star, or be kept by a rich man, by sheer dint of schmoozing and whoring and faking it till she makes it. She’s a phony, a social climber, and a parasite.

But under all this, surely there beats a heart of gold.

No, not really. Not at all. Sally is selfish, immature, insensitive, rude, and neurotic. We are supposed to feel for her because she pines for her neglectful father. (There is no mention of a mother.) But feeling pain doesn’t make you a good person. In fact, bitterness over festering wounds is the most common excuse for monstrous behavior. Strip away Sally’s gaucheries, neuroses, and machinations, and you won’t find a little rosebud of sweetness. You’ll just find a howling void of nihilism.

Minnelli’s songs all have mediocre music and lousy lyrics. Her catchiest number, “Mein Herr,” is about being a hypergamous gold-digger. When she meets a nice young homosexual, who beds her out of pity, she thinks “Maybe this Time” it will last. Then there’s her duet with Joel Grey, “Money, Money,” which informs us that “Money makes the world go ’round,” a witless ditty in which vulgar Marxism meets just plain vulgar. (By every measure, it is infinitely inferior to ABBA’s “Money, Money, Money.”) I’ll have a few words to say about her grand finale later.

The basic plot of Cabaret is that a young homosexual Englishman, Brian Roberts (Michael York, looking conspicuously wholesome), comes to Weimar Berlin. He finds lodging at a rooming house full of bohemian types, including a streetwalker and a pornographer who both turn out to be Nazis, as well as Sally Bowles, who is right across the hall.

The strait-laced (though gay) Englishman meets the brash American in clown makeup, and an unlikely friendship begins. Sally introduces Brian to the Kit Kat Klub, finds him work translating pornography, offers him her room for teaching English lessons, and generally inserts herself into his life, to the point of seducing him. Brian seems to sleep with her out of pity.

Once Brian and Sally are a couple, hypergamous Sally takes up with Maximilian, a fantastically wealthy aristocrat who finds Sally and Brian entertaining. He showers them with expensive presents, dangles the prospect of an adventure in Africa, beds both of them, then loses interest.

One of the most famous scenes in the film takes place as the trio returns to Berlin from Maximilian’s country estate. Maximilian has explained how the Nazis are hooligans, but useful for stopping the Communists. Once the Communists are defeated, people like Max will rein in the Nazis. As they enjoy lunch at a beer garden, a handsome blond youth begins singing. It is standard German Romantic or folk fare, with stags, forests, the Rhine, babies, and so on. Then we see that the young man is wearing the uniform of the Hitler Youth. The song takes on a more martial and strident air with the chorus “Tomorrow Belongs to Me,” and virtually the whole crowd joins in signing. “Still think you can control them?” Brian asks Max.

The song is pure, calculated kitsch, the product of two Jewish songwriters, and yet it is better—and seems sincerer and more real—than anything else in the film. The scene is crushingly unsubtle, an exercise in ritualistic goy-hatred. These Hollywood Nazis are supposed to seem sinister and repellent, but they are infinitely healthier and more appealing than the smug and decadent Max and Brian, much less anything on stage at the Kit Kat Klub.

The most wholesome love story in Cabaret is between the impoverished businessman Fritz Wendel and the Jewish heiress Natalia Landauer, who meet through Brian, their English tutor. Fritz pursues Natalia, but there’s a hitch. Jew-gentile relations are at a low ebb in Germany. But Fritz has a way out. He’s actually a Jew. He was merely pretending to be a Christian, because once you are a member of the vast majority in an individualistic society, people notice you and invite you to parties and cut you in on business deals. It is a farcical distortion of the truth. Crypto-Jews don’t lose touch with the Jewish community. The whole point of crypsis is to enjoy the advantages of belonging to both communities. When Fritz admits to Natalia that he is an apostate who has lied to her and everyone else, she naturally agrees to marry him. It is supposed to be heartwarming, but morally normal people find it bizarre and repugnant.

Brian and Sally’s relationship has a less happy ending. Sally is pregnant. Maybe the baby is Brian’s. Maybe it is Max’s. Sally wouldn’t dream of asking Brian to pay for the abortion, though. She’ll just pawn the fur coat that Max bought her. Brian has another idea. He proposes marriage. He doesn’t care if the child might be Max’s. Decadence doesn’t seem so divine anymore. Berlin is hell. It is a rat race in pursuit of shallow and unsatisfying pleasures. Brian sees marriage and fatherhood as a chance for both him and Sally to escape and have a normal life. He’ll teach at Cambridge. Maybe there will be other children.

Sally is touched that someone would be willing to spend his life with her. But marriage would require some changes: fidelity, for one; sobriety, for another; plus unselfishness toward babies. It also wouldn’t hurt for her to pick up some of the social virtues necessary to live in a normal community. But the biggest change would be to stop chasing her absurd dream of becoming a movie star. Sally thinks about it a bit, then skulks off and has an abortion in secret. Some viewers see a strong, independent career girl strongly and independently being strong and independent, or something. And they applaud. Healthy people see that, in the end, hedonism and individualism are just a nihilistic death cult.

Brian is horrified, of course, but probably realizes he has dodged a bullet, because Sally Bowles will never change. Besides, who would want children with her looks and personality disorders? This, in truth, is the most enlightened perspective on the matter, but the only people who would voice it in Cabaret are the hated Nazis.

Brian returns to England, and Sally returns to the Kit Kat Klub, where she sings her final song, “Cabaret,” in which she informs us that “Life is a cabaret, old chum” and then tells the story of her old flatmate Elsie, a whore who died of drink and pills and was the “happiest corpse she’d ever seen.” Then Sally vows that, instead of having a normal life, “When I go, I’m goin’ like Elsie.” It is an open celebration of nihilism. It is particularly grotesque from the lips of the daughter of Judy Garland, who was found sitting dead on her toilet, aged 47, after a lifetime of abusing alcohol and downers. Liza Minnelli herself has lived to be a ripe old chum, but one wonders how many lives were cut short because of her glamorization of a death cult.

Cabaret ends with another icky song and dance from Joel Grey. The final shot is a distorted reflection of the audience, in which we see a number of Nazi stormtroopers. Are they in the audience because they are hypocrites, dipping into the fleshpots while railing against them? Or are they there to bust up the place? In truth, it was a bit of both. Of course, the filmmakers want us to mourn the passing of Weimar. But healthy viewers see something very different, a message that Goebbels himself would have approved: Weimar was a disease. The Nazis were the cure.

The Unz Review, July 1, 2019