Confronting the Ethnomasochists on the High Seas:

Alexander Schleyer’s Defend Europe

Posted By

Michael Walker

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

To listen in a player, click here [2]. To download the mp3, right-click here [2] and choose “save link as” or “save target as.” To subscribe to the CC podcast RSS feed, click here [3].

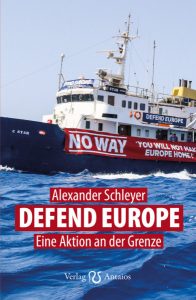

Alexander Schleyer

Defend Europe: Eine Aktion an der Grenze [4]

Steigra: Antaios Verlag, 2018

It was reported in The Guardian [5] in 2016 [5], and elsewhere, that shortly before his execution (to Hillary Clinton’s delight) in 2011, Muammar Gaddafi of Libya had warned Tony Blair in two telephone calls that his own overthrow would bring about the collapse of the Libyan barrier. Gaddafi claimed that it was his government which was playing a key role in holding back mass migration from Africa to Europe. He also warned that his country would become a magnet for Islamist terrorists if his regime was overthrown.

Subsequent events have proved Gaddafi right. Following the Western-backed coup which destroyed him, Libya has sunk into chaos, its infrastructure is in ruins, it is a land torn apart by warring factions, and it has become a haven for Islamic fundamentalists. Today, smuggling migrants to the Libyan coast and then on across the Mediterranean to the promised lands of Europe is big business for human traffickers. Many Africans will pay thousands of dollars to be transported by traffickers who operate on the fringes of – or beyond – the law. These traffickers are aided and abetted – certainly indirectly, and probably in many cases directly – by multifarious nebulously-funded pro-migrant NGOs.

Meanwhile, far from taking up the challenge posed by the migrant wave with any intention of stopping it, leading European politicians, journalists, and other prominent personalities have expressed sympathy for anyone who rescues migrants and brings them to Europe; if that means illegally, they don’t care.

Alexander Schleyer, the author of Defend Europe, is described on the book’s flyleaf as a freelance writer, flaneur, and former Marine living in Vienna. The book is his account of his experience on board the ship C Star as navigation officer. The C Star was manned by a group that was seeking to achieve the very opposite of the pro-migrant NGOs, for they wanted to discourage migrants from crossing the Mediterranean. The crew’s exact role was to monitor pro-migrant NGO activity in the Mediterranean with a view toward filming and recording it, especially when they suspected that the NGOs were acting in disregard for international law. From day one, this non-violent and entirely legal and legitimate initiative was opposed and denounced by a chorus of the righteous, and any number of “touchy feely” liberal media commentators and their friends in national and regional parliaments, as well as the pro-migrant NGOs themselves. These NGO’s themselves receive help and encouragement from their many friends in politics and the media. In reading this account, the reader will gain the impression that both the NGOs involved in transporting migrants and the many who support them considered themselves – and still consider themselves – beyond criticism and above the law, national and international.

Defend Europe’s writing style is uneven, with down-to-earth practical accounts juxtaposed with philosophical reflections. This awkward style doubtless reflects the writer’s own unusual combination of careers as student of philosophy and Marine. Philosophical reflections are mixed in clumsily with descriptive interludes describing life at sea and the hardships of a life on the waves, reminiscent of Jack London or Joseph Conrad. The writing is rough and unpolished – or to describe it more positively, it is unaffected. Schleyer tells his tale not eloquently, but I suspect truthfully. He is a man who is risking his career, his reputation, and even his life to do something European states have failed to do. There is opportunity and justification for bragging here, but Schleyer does not boast. His is a book written by a man of action with a story to tell and an example to set, and this is what he does, not more and not less.

It is not clear to me whether it is for want of experience in what he is writing about, or whether for other reasons, but the book offers nothing which would explain the presence of the C Star in the Mediterranean waters or of the writer on board. When the book begins, the ship is already in the Red Sea on her way to the Mediterranean. This lack of a background story to this book is a major failing. What was the emotional context of Schleyer’s decision to join the C Star? Who made the decision to take part in this adventure? Perhaps confidentiality demands discretion in some respects. If that is the reason for Schleyer’s silence, it is laudable, but carried much too far. One thing is certain: Neither fame nor money can be Schleyer’s motivation. I doubt there was much money to be made in the venture, and outside a (too) small group of admirers – a group which will hopefully grow as a result of this account – the adventure is unlikely to achieve much fame. Early in the book, the driving motivation does become clear, however, although it is not presented in anything like a statement of belief or a manifesto, but the following excerpt indirectly explains why Schleyer decided to act as he did, in a mixture of philosophical and intellectual reference, fantasy, hard-headed realism, and nonchalance:

Now [the C Star], with her multinational crew, was crossing the Red Sea in the direction of Southern Europe and North Africa to pick up activists of the Identitarian movement, whose plan it was to have a look at the activities of the so-called rescuers of the refugees – activists who were repeatedly falling under suspicion of operating as transporters for illegal migrants rather than carrying out rescue operations. . . . This odyssey was and is a political act consisting for the most part of sacrifices, nights of despair, unbelievable pressure, and cruel setbacks. It was the order of inner conscience and a burden imposed upon us as being the only and last of our generation who could put up a sign of resistance. This sign should not, and may not, be a herostratic act, and not an aesthetic self-indulgence. The admixture of political romanticism and media savvy making up the trait of what Lenin called “the realistic dreamer” is the essence of the Identitarian movement. (pp. 10-11)

There is, then – to write in the author’s style – a definite element of Spenglerian fatalism and pessimism in Schleyer’s account, the upside of which is a disarming modesty. This fatalism (attenuated, to some extent, given that if it were not the case, there would be no C Star adventure to write about in the first place) never implies that action is futile. What is charming about this book is its modesty: the writer has been through hell and does not boast of his adventure, nor seek adulation. He simply tells us, “This is what I did, and this is what it was like.” It makes his tale all the more shocking.

Particularly shocking is the apparent collusion between highly-placed operators with close links to governments and the financing and protecting of the illegal smuggling of migrants into Europe. What I repeatedly asked myself while reading this book is, how is it possible that European governments responsible for protecting their citizens are not doing what the harassed crew of the C Star undertook? How is it possible that European governments do not undertake a consistent, consequential, and efficient protection of Europe from illegal penetration? How low we have sunk and under what treacherous, effete, and enfeebled rulers and spokesmen have we fallen that this action was in any way necessary! Defend Europe reminds me of a citizen who is worried about the accumulation of rubbish in his street; decides to gather rubbish on his own initiative, at his own cost, and in his own free time; and is then hampered and demonized for his pains by the very utility services whose job it was to clear the rubbish in the first place.

In the second chapter of the book, “Mächtiger Gegner” (Powerful Opponents), Schleyer refers to Hope Not Hate, an NGO backed by the well-known internationalist George Soros, who, according to Schleyer, donated $94,740 to Hope Not Hate between October 2013 and May 2014. At the time that this book was written, Hope Not Hate was focusing its attention on NGO operations in the Mediterranean and supported them by denouncing the C Star crew and sabotaging their work. But Hope Not Hate is by no means the only recipient of Soros’ largesse, and Schleyer also cites Simon Wald, a blogger who claims to have proved that SOS Racisme, the European Women’s Lobby, the European Network against Racism, and Ligue des droits de l’Homme each receive $100,000 from Soros-financed foundations every year. The total number of NGOs financed by George Soros, according to Simon Wald, is 91, the lowest annual grants amounting to $8,000 and the biggest to $260,000. Hope Not Hate, notes Schleyer, openly boasted on its Website that it sought to prevent crowdfunding for the C Star operation and blocked the crowdfunding platform for weeks. If true, this would itself presumably constitute an illegal act, and one wonders why Hope Not Hate has not been prosecuted for it.

Another attempt was made to stop C Star from ever reaching the Mediterranean by using the media and government outlets to spread the false rumor that the C Star was carrying armed mercenaries. And at one point, the ship’s rudder pump system was switched off, nearly causing a collision. Much of the book is taken up with an account of the spreading of false rumors, harassment by the authorities, and technical sabotage.

Far from carrying mercenaries, C Star’s intentions were so anodyne and so devoid of violence or warlike intent that any objective reader should be shocked at the ire and chicanery which the C Star’s plan of action caused, even before she had reached the Mediterranean. The crew’s intention was nothing more belligerent than observing and filming NGO activities, especially those operating close to the Libyan coast, where they were transporting migrants. The violence of the reaction to them is evidence in itself, if evidence is needed, that operations to “save” migrants in the Mediterranean encouraged human trafficking and included illegal activity on its own account. Pro-migrant NGOs are suspected of being in contact with smugglers, and have acted as a kind of “taxi service” transporting migrants across the Mediterranean.

To prevent the C Star from observing how smugglers and “rescuers” coordinated their activities, sabotage, fraud, threats, and even arrest by the local police were all tools used to try to stop C Star’s mission in its tracks. For Tintin aficionados, this sabotage recalls the tricks played to thwart the Aurora by Bohlwinkel, President of the Bohwinkel Bank. Just as Captain Haddock was informed by Golden Oil under instructions from their owner – the bank – to lie to Haddock by telling him that there was no diesel available, so Schleyer recounts how the C Star was sabotaged by being sold diesel fuel mixed with water, which not only severely damaged the ship but was actually life-threatening given that it caused the electrical communications to break down and also created an imbalance in the fuel tanks, the water pushing the prow of the ship dangerously low into the sea.

Time and again, Schleyer relates the manner in which a vast, efficient, and highly organized network of pro-migrant forces sets out to impede the C Star. Especially dismaying is the networking between antifa groups, politicians, lawyers, NGOs, and heads of state. The fact that the writer does not delve into conspiracy theories, his account being strictly a factual record of events, makes his account of the actions to prevent the C Star from reaching her destination all the more persuasive. The stakes are high. Even Die Welt, a mainstream publication likely to play figures down rather than up, claimed on May 23, 2018 that seven million Africans, transiting from Algeria to Jordan as well as Turkey, are poised to cross over into Europe at their first opportunity. That figure does not include Morocco, perhaps because the King of Morocco is still playing a role similar to Gaddafi’s and keeping migrants at bay (albeit after being bribed to do so by the European Union).

Schleyer does not seem to be the kind of person to obsess about the existence of secret plans and societies and a conspiratorial network of one kind or another, but he nevertheless notes:

The list of apparent manipulations, sabotage, and illegal acts to which we were subjected during our short journey is so long that it is hard to explain without accepting that there was systematic intervention from government circles, the military, secret services, and mafia structures. (p. 173)

Quite.

There are occasional flashes of humor, or at least irony, in the book. For example, on page 80, Schleyer tells us that the Asian crew of the C Star at first believed that the rumor about mercenaries must be true. The C Star crew was more than once prevented from docking to refuel, and when the crew landed in Turkish Cyprus, they were all imprisoned on charges of smuggling mercenaries. Schleyer provides a grim description of Turkish Cypriot prison conditions that will confirm most people’s preconceptions of what such a jail must be like. It seemed to the Asian crew utterly implausible that European nations could be treating Europeans in such a manner if the crew’s sole “crime” was to monitor aid to illegal migrants. The logical conclusion from the point of view of the Asians on board was therefore that the charges of transporting armed mercenaries must be true. For them, it was literally unbelievable that illegal migrants could be supported in their attempts to cross into Europe by state-owned associations in Europe itself.

The efficient and obviously well-financed operations of such ultra-Left-wing groups are demonstrated by the ease with which they could organize sizeable protests in the right place and at the right time – even when the place was an obscure Greek port – to prevent the C Star docking and resupplying. In this story, illegality lies entirely on the side of the pro-migrants – up to and including the action by Golfo Azzuro, which was owned by the NGO Open Arms, when it approached the C Star and come perilously close to forcing a collision – an incident that can be viewed on YouTube [6].

C Star’s action, despite all trials and misgivings, was successful. Its success was visualized in the symbolically triumphant gesture of attaching a “Defend Europe” sticker to the hulk of a Golfo Azzuro dinghy – indicative of raising awareness, especially in Italy, of the earnestness of the situation.

The high point of the book is the confrontation between a Libyan Coast Guard officer, Captain Abdul Bari, and the Golfo Azzuro, when it had anchored a few miles off the Libyan coast with its lights switched on all night for reasons which are not hard to guess. It gave me joy to read the account of the determination of the Libyan Coast Guard to force the pro-migrant humanitarian internationalists out of Libyan waters. The crew of the Golfo Azzuro later mendaciously tried to claim that they were chased away not by the Libyan Coast Guard, but by pirates, a claim disproved by the video of the encounter. It is not clear who, if anyone, informed the Libyans of the presence of the Golfo Azzuro. Certainly, the crew of the C Star considered their role as being an informative one, and when they were notified of what was happening, the Libyan Coast Guard was prompt to take the necessary action to force the Golfo Azzuro to leave. From the Captain’s language and tone, it is clear that the Libyan Coast Guard is entirely unsympathetic to the pro-migrant NGOs, and Captain Bari demonstrates a robust common sense and disgust towards them that is woefully lacking among many Western leaders.

Since this account was written, the struggles between pro-migrant NGOs and those opposed to them – even though they are seldom reported on – continues. It is impossible to evaluate (at least from this book alone) the extent to which, if any, the C Star’s actions contributed toward hardening European attitudes toward human traffickers, especially among those whose decisions make a difference. In April of this year, the Dutch government introduced stricter rules and safety measures for rescue boats. The new rules apply especially to “organizations with idealistic aims”; for example, to SeaWatch-3, a rescue ship operating under the Dutch flag. Until April, the ship could register as a “sports ship,” thus evading the standards required for transport ships – a trick to which Schleyer refers in Defend Europe. The President of SeaWatch complained strongly about the new rules, which he described as an “attempt to undermine our rescue work.”

In the meantime, Italy’s Minister of the Interior, Matteo Salvini, has issued an injunction against illegal migration, and Italian ports now deny access to ships carrying illegal immigrants. The subsequent drop in such migration to Italy has been dramatic. In 2018, 13,430 illegal immigrants were recorded as landing in Italy from January 1 to March 29; during the same period in 2019, the figure was 1,561. Salvini’s injunction includes a penalty for infractions. Every ship which brings illegal immigrants to Italy is subject to a fine of between 3,500 to 5,500 euros per immigrant.

Despite this, pro-migration activists will not give up their determination to deny European states all control of their borders. The chairman of the German Protestants, a prelate named Heinrich Bedford-Strohm, has visited SeaWatch to express his solidarity with the group in its dispute with the Italian and Dutch governments. He made an appeal to politicians not to hinder SeaWatch in its mission. According to the German conservative paper Junge Freiheit on June 7, 2019, the German Protestant churches are actively financing the pro-migrants, and donated 100,000 euros for the purchase of the plane Moonbird, which patrols the Mediterranean and can presumably warn NGO operatives of any opposition which might be heading their way. There are many influential and powerful groups always ready to spend money on a “good” cause.

For its part, an increasingly nervous European Union has been making payments to the governments of Morocco, Turkey, and more recently Libya to help keep millions of “refugees” at bay. This book, which was published in 2018, makes no mention of any connection between the hardening of attitudes in Europe and what the C Star achieved. Perhaps there is none, or if there is, perhaps the writer does not wish to draw attention to it. Schleyer is most definitely not a man seeking to glorify himself or those with whom he worked.

Two things can be taken away from this account. One is confirmation of the cooperation and networking between refugee organizations, anti-fascist groups, the churches, Left-wing politicians, foundations backed by big money, and journalists. It cannot be stressed enough that the C Star was not seeking to attack or even threaten anyone; her crew was unarmed and was committed to carrying out no illegal acts. They only wanted to report on the activities of the pro-migrant NGOs to coastal authorities if they were committing illegal acts. The other is that even humble actions such as those of the C Star make a difference. Nobody is so insignificant that their actions do not count.

Were Europe confident rather than decadent, the C Star initiative would have been utterly unnecessary. But sadly, Europe is indeed decadent rather than confident. Europe is riddled with subversive elements in high positions determined to utterly destroy it, and so this and similar actions were and continue to be necessary. The story of the C Star has the dimensions of something great. It should be an encouragement to all those who are at risk of sinking into that pessimism and fatalism which so often work as a pretext to excuse pusillanimity and inactivity. The C Star adventure shows that heroism and commitment can still make an impact.

The writer’s last words are characteristically diffident, but hugely significant. The C Star’s expedition was, he writes, “the adventure of our lives” (p. 183). Fighting the good fight will not appeal to youth if it is presented merely as a “duty.” It must also be seen in the light of what all life-aspiring youth yearns for: the light of adventure.