Central Park Wilding Revisionists & Deniers

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledWhen They See Us (2019)

Directed by Ava DuVernay

The Central Park Five (2012)

Directed by Ken Burns, Sarah Burns, & David McMahon

Wilding is back in the news, although with a completely different spin than when it showed up the first time in the spring of 1989. To explain, on the night of April 19, 1989, a group of thirty or more Africans and “Latinos” with considerable African ancestry went on a rampage in Central Park that the press came to call “wilding.” The blacks beat up homeless people, white bikers, and pedestrians. One woman, Trisha Meili, whom the press came to call “the Central Park Jogger,” was beaten and raped. She wasn’t found for several hours, by which time she had lost eighty percent of her blood, and she was in a coma for days after the attack. Afterwards, she couldn’t even remember it.

The police had been alerted to the rampaging dindus and moved in to make arrests. As they started to question them, the names of what would become the “Central Park Five” stood out for being the worst offenders in the bunch. The police arrested Yusef Salaam, Antron McCray [2], Raymond Santana [3],[1] [4] Kevin Richardson [5], and Korey Wise [6]. All five admitted to having assaulted passersby, and both the evidence and eyewitnesses corroborated their assertions in court. After police grilling, all five admitted to Meili’s rape. (I’ve linked their videotaped confessions above – Salaam’s confession was not filmed.) In their confessions, they didn’t so much implicate themselves as they implicated all the others. None of them mentioned the perpetrator whose DNA was discovered at the scene of the rape.

Before proceeding further, one needs to mention that in 1989, black crime in the United States had been on a thirty-year high, and nearly all the big Northern cities were being poorly run by black mayors. (New York City itself was about to get David Dinkins in 1990.) The causes for this were multifaceted. Its first cause was the arrival of a large number of backs to the Northern cities in a wave called the Great Migration that started around 1910 and ended in the 1990s, when blacks began moving to Atlanta. The next was a go-easy policy on criminals that began as early as the late 1950s and didn’t end until 1994. Finally, there was the “civil rights” revolution that started in the 1930s and culminated in the mid-1960s, triggering white resistance but causing major social damage. And in the 1980s, crack came on the scene, and suddenly a great many black men had money, guns, and reasons to use the latter. One could hear gunfire day and night in every big city on the East Coast in the late 1980s.

By 1989, every Northern city that had a large black population had gone to ruin. In New York City, the smell of urine was everywhere, and entire neighborhoods had decayed; trees were growing in the living rooms of abandoned Victorian-era apartments. Graffiti covered the subway stations and trains. Muggings were rampant; in 1991, Donald Trump’s own mother was severely injured in a mugging [7]. “Youths” commonly jumped the subway turnstiles (one of the Central Park Five actually did that on the night of the wilding). There was also the metapolitical disaster of gangsta rap. The vulgarity of that genre was something quite new at the time. Nowadays, f-bombs and n-words in songs are packaged with a tight corporate bow and sold to middle school girls, but in 1989 it was all very shocking, and it contributed to the general feeling of decline and Africanization. I recall in 1989 that 2 Live Crew seemed to be the most popular rap group; one wigger on my middle school bus be-bopped 2 Live Crew’s obscene underground hit [8] every morning in the months prior to April 19, 1989.

When it came to forensic technology, the use of DNA was in its infancy. The technology was new, juries had never heard of DNA, and there were no DNA databases that police could use to quickly identify offenders. Thus, DNA evidence could not yet secure a conviction.

The Central Park Five were tried and convicted of Meili’s rape and for other attacks [9]. There was a great deal of evidence [10] implicating the five; they mentioned the fact that the victim’s Walkman was stolen [11], which was a detail only the perpetrators could have known. The confessions are matter-of-factly given, with many details. Eventually, Matias Reyes, the man whose DNA was discovered at the scene, confessed that he alone had conducted the rape [12]. Interestingly, and perhaps tellingly, Reyes starts out describing conducting crimes in a wolf pack in his videotaped confession, but he doesn’t name anyone else. His confession is probably not completely true, and it is evasive and confusing. The Netflix miniseries uses considerable dramatic license to clarify and clean up the confession. Although the Central Park Five were convicted of more than just the rape, as a result of Reyes’ confession, all their convictions were vacated after a campaign led by a Jewish District Attorney, Robert Morgenthau. The five were in fact awarded an enormous sum of money in settlements with the City of New York.

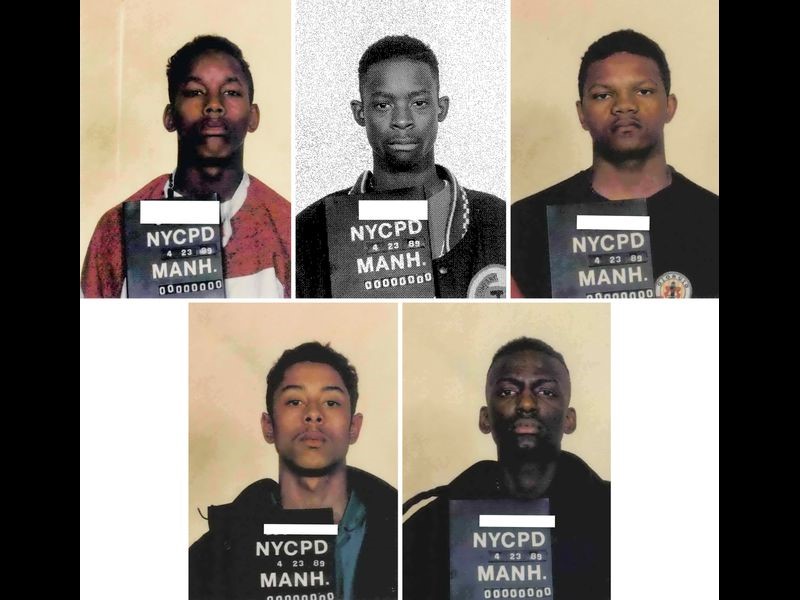

[13]

[13]Above are the mugshots of the Central Park Five from an article in the New York Daily News [14]. The reader is encouraged to draw their own conclusions as to the impression they would make as part of a wilding “wolf pack” in Central Park.

If the Central Park Five case were investigated today, the DNA would be used to secure the arrest and conviction of Matias Reyes. After his arrest, Reyes would have been questioned by police in a way so as to give up his accomplices. And even if the Central Park Five were not guilty of this crime, the five still should have been tried and convicted for the other assaults in the wilding rampage.

One thing is certain: Reyes was of a similar racial and age background as the others who were accused. He conducted the assault at the same time and in a location very close to the others. It therefore isn’t difficult to conclude that Reyes could have been wilding with the others and then broke off alone to commit the rape. Conversely, he also could have committed the rape with the others and it was only by chance that he ended up being the only one to leave traceable DNA, or he might have done it with other wilding blacks who were not part of the Central Park Five. Evidence on the victim’s body implied multiple attackers, so it is very likely that he was not alone. Regardless, the Central Park Five didn’t mention Reyes in their confessions, which they should have had they been there and their DNA was not discovered at the scene. In a just world, the Central Park Five would not have been convicted of the rape because there can be reasonable doubt as to their guilt, but there is also ample evidence that they were very close by, committing other crimes, and that their wilding made the rape easier to accomplish.

From my own experience in investigating rapes and other assaults by blacks – this experience having been limited to being a combat arms officer using the US Military’s Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) and Army Regulation 15-6 – the Central Park wilding wolf pack matched a pattern I’ve also seen. That is to say, blacks are comfortable joining a group and then committing crimes with them, including assault, rape, or gang rape. And once they get going, no individual black is able to stop himself or the others. They are also willing to engage in these crimes with other blacks who they don’t know. Blacks in the military, including non-commissioned officers, do things very much like wilding even on military bases – it wasn’t just a “Vietnam era” thing, either. Many of these blacks are clever enough to outwit an inexperienced authority figure, such as a Second Lieutenant on his first detail[2] [15] as Staff Duty Officer, but not clever enough to fool a more experienced soldier, such as the Master Sergeant from the S-3 shop who walks by and sees something strange.[3] [16]

Forgetting in White: The Wrath of the Awokened White Liberal

What is so interesting about the Ken Burns movie is that it shows how American society anesthetizes itself regarding African pathology. His film matches a traditional, progressive white pattern in American history: whites – usually white progressives – dismantle institutions that manage Africans while shouting about justice; with the institutions in tatters, blacks progressively become more criminally inclined. At first, this rising pathology is ignored or explained away, but eventually, it only takes one incident to elicit a white response as they grow increasingly tired of all the mischief. Whites then establish a new form of control that lasts for several decades – until white progressives again move to dismantle that system, and black pathologies increase again.[4] [17]

I’m at a loss to explain why the white “progressive” moves to dismantle these institutions while crying about injustice and racism. Why don’t white “progressives” encourage American blacks to move to Ghana in order to get away from hopelessly racist whites and thus break the cycle permanently? Regardless, there is a religion of Negro Worship among whites, especially those who are Yankees who live far from blacks. Ken Burns, for example, lives in whitopian New Hampshire.

The key thing about Negro Worship, and those whites who believe in “civil rights,” is that they misread data. Ken Burns’ film does this in several ways. First, it implies that the police went after the Central Park Five for no reason at all. In reality, the NYPD’s only mistake was to stop looking for the “sixth rapist” as DNA technology kept advancing. Had they done that, they wouldn’t have been subjected to a Jew-African hit job following Reyes’ confession. Additionally, the prosecutors, Linda Fairstein [9] and Elizabeth Lederer, were not really rewarded for their work. They were then and are now subjected to the vilest slanders and insults for their work on the case.

Second, there is the research conducted by Sarah Burns (Ken’s daughter) into the New York media’s vocabulary regarding the Central Park Five. It was in fact this project that led to the film. Sarah Burns noticed that the New York press used the same terms as that of the Southern press during the Jim Crow era (1890–1930). However, she doesn’t draw the obvious conclusion that two different communities – conservative Southern agrarian whites and progressive, urban New Yorkers – were likely to use the same metaphors and hyperbole because black crime was impacting both of them in the same way. The common denominator is black crime, and white “racism” is a rational response to this.

And the film is disingenuous from the get-go. The opening states that the New York Police Department chose to not comment at all, but in an interview with Ken Burns, the following exchange occurs [18]:

John Miller (NYPD Deputy Commissioner): [The NYPD detectives who investigated the crime] were very frustrated they weren’t allowed to be part of the film. They wanted to tell their story.

Ken Burns: And we did ask, consistently.

John Miller: [Talking over Burns] Repeatedly. There is not a detective on this case who doesn’t say they didn’t call [Burns] fifty times.

Ken Burns: And we would love to have them involved, but adding “probably” to this isn’t right.

As mentioned above, Ken Burns’ film downplays the very real mayhem that the Central Park Five committed along with the rest of the wilding wolf pack. In their own words, however, this is what the five have to say [19]:

Yousef Salaam: Well, April 19th, 1989 was a turning point of life, so to speak, you know. You go from hanging out with friends, thinking you are going to, you know, go skateboarding in the park, or walk around the lake . . . to mayhem, so to speak, breaking out.

Kevin Richardson: . . . everything became a blur . . . I seen a group of kids and I followed them . . . that night I followed them into the park.

Antron McCray: It was real hectic, it was crazy. Standing there and watching someone get beat . . . I couldn’t believe it, but I stayed there, watching a man get beat.

They are admitting that they were part of a group doing violence, and their statements are vague and use passive voice. Regardless, what is indisputable is that these men were involved in wilding.

Burns also discusses a timing discrepancy in the wilding incident. Based on the jogger’s presumed route and rate of speed, it is indeed possible that the Central Park Five were attacking people in a different location from where the rape happened – but again, the Central Park Five were beating people in the park at the same time.

It pains me to critique Ken Burns. I have watched most of his films and enjoyed them. I believe that much of what he says in The Civil War and The Vietnam War are true and even-handed. In this case, however, Burns is pushing his Negro Worship religion, and he could very well be complicit in creating a “surrender to black crime” social mood that may well end in disaster.

Forgetting in Black: The Traditional African Cry of Innocence & How Blacks See Things

Ken Burns’ film is a documentary that purports to state the facts and claims to be searching for the truth. When They See Us is a fictional narrative based on a true story. One thing I’ve noticed since becoming a white advocate is that movies about blacks who are put in prison always share one thing in common: the crime that lands the protagonist in jail is always sloppily shown. I think that many blacks, especially the low-IQ criminal type, really don’t understand how their impulses get them in so much trouble. Movies based on their experiences end up showing the protagonists in a situation where they are just playing basketball until, suddenly, “mayhem breaks out.” In When They See Us, the wilding incident is shown in this way.

The movie then goes on to focus on the arrest from the Central Park Five’s point of view. The movie highlights their police interrogation and then glosses over the many witnesses and evidence that were presented in the two trials (the five were tried in two groups). The miniseries focuses on Meili’s rape, with the foreshadowing and story arc focused on showing that there was reasonable doubt about their guilt for the rape while downplaying their guilt for the other assaults.

When I researched this case myself, I discovered several things that were not shown in the miniseries. The claim of false confessions was presented in the trial, and the jury did think about it – hard. Their deliberations lasted for twelve days in the first trial. The prosecution also said they had DNA from an unknown perpetrator. They believed that there were more rapists than just the five on trial. Black activists behaved horribly throughout [20]. Many accused Meili’s boyfriend of the rape. Furthermore, while the prosecuting attorneys acted well within the bounds of the law and the ethics of their profession, Yousef Salaam’s defense attorney, Bobby Burns, a Negro divorce lawyer, fell asleep during the trial. Falling asleep at inappropriate times is a black stereotype and I’ve witnessed it many times myself. One defense attorney went on to insult Meili on the stand [21], which reflected poorly upon himself and his client.

The director, Ava DuVernay, is carrying out a metapolitcal attack in this film. Like in the Ken Burns film, the police and prosecutors’ sides of the story are not shown. DuVernay didn’t even pretend to be objective, however, stating that [22] “Linda Fairstein tried to negotiate conditions for her to speak with me, including approvals over the script. So you know what the answer was to that, and we didn’t talk.”

Conclusion

If you don’t want to be falsely convicted for a crime like rape, you shouldn’t commit other serious crimes simultaneously, such as the Central Park Five were doing along with thirty other blacks. If arrested and interrogated by the police, say nothing and get a lawyer. Had this occurred, the Central Park Five would have gotten off with a minor sentence for the other wilding assaults, and Mathias Reyes might have been caught quicker.

From the perspective of law enforcement, what happened to the Central Park Five is unlikely to recur. There are now DNA databases which allow investigators to quickly mine the data for a match. Technology has improved to the point where positive identifications can be made from small DNA samples, unlike how it was in 1989. Also, the cell phone and security camera revolutions have come; today, eyewitness testimony can often be backed up with actual footage. Also, social media is a walking evidence locker of information. Crime didn’t pay in 1989, and it pays even less now – assuming the police are allowed to arrest criminals.

The black community is fundamentally sympathetic to criminals. Even well-adjusted, highly intelligent blacks who you like at work often have very close relatives who have been justly convicted for serious crimes. The black community likewise shows no sympathy for the white victims of black crimes. There is no formal recognition of just how dangerous their community is to themselves and others. Black religious leaders don’t condemn crime; they only condemn those whites who fight it.

Of course, blacks are victims of crime as well, but they are not always innocent victims. There is a huge moral difference between an elderly white lady who is killed in a random shooting than when a young black man is killed after he has gunned down a rival drug dealer earlier. Black activists have to be made to understand that since they cannot control the crime in their own communities, whites – such as those who investigated and prosecuted the Central Park Five – will and must. Civilization depends on it.

The Negro-Worshipping white guilt crowd is also dangerous. Morally posturing over a case such as that of the Central Park Five ultimately justifies lesser crimes, such as assault and robbery. This sanctimony conceals an even more unjust situation: that of ceding our civilization to Africans. Jump turnstiles, defacing subway cars, or attacking random people in a park are not civil rights. (Likewise, Africans don’t have an inherent right to have access to a civilization they cannot maintain – but I digress.) Crime was stopped in the early 1990s via a twofold strategy: arresting people for little crimes, given that the same people who jump turnstiles also go wilding; and putting criminals in prison for a long time.

The lesson to be drawn from this is that the United States can reduce crime simply by moving blacks to some secure Pale of Settlement. However, if the police arrest people committing minor crimes, like jumping the turnstiles in the subway or doing a smackdown on someone sleeping on a park bench, then blacks that don’t commit crimes will still be able to partake in white civilization, and equality can continue to be the Big Lie underlying American society. But if we continue to follow the ideas of the white guilt crowd, we could be setting America up for a return to the crime wave of the 1980s.

Notes

[1] [23] Raymond Santana’s father was a white Puerto Rican, and his mother was mostly black. This wilding attack was carried out by an African wolf pack; it wasn’t really New World Spanish whites, plus espomolos, castizos, or harizos joining against white devils.

[2] [24] They usually can’t fool a Second Lieutenant on his second tour as Staff Duty Officer, however.

[3] [25] Another thing I found is that blacks don’t have good comprehension skills. The blacker and more African they are means the likelier they are to be unable to navigate or to tell where they are when in an unfamiliar place, or to accurately know at what time things have occurred. This might seem harsh to those who have no experience with managing blacks, but it is nonetheless often true. They also have a difficult time grasping abstractions, but they are often able to conceal this as they are typically very socially competent.

[4] [26] We can see this in history. At the start of the nineteenth century, American slave owners followed George Washington’s example and manumitted their slaves. Those who didn’t still lessened restrictions on their slaves. What followed was a barely-averted slave uprising in 1822, and the Nat Turner slave rebellion in 1831. White slave owners changed the laws regarding blacks and slaves, introducing the Fugitive Slave Act and issuing passbooks for slaves. Then, along came the Civil War. The slaves were freed, but by the 1870s, Northern whites were tired of supporting Southern blacks. When blacks began to move to the cities in the 1890s, the South, and to a lesser extent the North, set up Jim Crow laws in response to black pathologies. In the 1930s, the Jim Crow laws began to be dismantled. From 1969 to 1994, whites incrementally set up systems to deal with black crime; today, this is again being dismantled.