Two Red Pills from the World of Chess

Posted By Spencer J. Quinn On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,763 words

For a race and gender realist, the world of professional chess provides an embarrassment of riches, even if very few in the English-speaking parts of it wish to claim them. In chess, men dominate – specifically white, Jewish, and Asian men. Only three women have ever cracked the top hundred rated players in the world, according to the international chess federation FIDE.[1] [2] And if current ratings [3] of girls and boys are any indication, this arrangement will maintain itself indefinitely.[2] [4] This has been borne out in a recent study [5] by retired chess master Bruno Wiesend, who debunked the prevailing dogma [6] which ascribed female inferiority in chess to lower participation rates. Another recent study [7] by Australian chess grandmaster David Smerdon demonstrates how patriarchal societies seem to help improve female participation rates in chess.

The first woman player to break into the top hundred was Georgian Maia Chiburdanidze [8], who reached forty-fifth in the world in 1988. Chiburdanidze was the women’s champion from 1978 until 1991. She was considered one of the best, if not the best, female player in history until the she was eclipsed by the explosion of female talent in the 1990s, coming mostly from Eastern Europe and China.

Leading the way was Judit Polgar [9], a Hungarian Jew who reached number fifty-five in 1989, when she was 12. She peaked in 2005 with an Elo rating of 2735, making her eighth in the world.[3] [10] Polgar is the youngest of the three famous Polgar sisters [11], all of whom became internationally-rated chess players thanks in large part to their father’s insistence on intensive training when they were little.

Much hoopla surrounded young Polgar in the 1990s when it seemed she had what it took to become a world champion. In 1991, she broke Bobby Fischer’s record of being the youngest grandmaster at age 15 and four months.[4] [12] She consistently held her own against the very best in the world, even to the point of beating former world champion (and still world number one) Garry Kasparov[5] [13] in 2002.[6] [14] Polgar was also the first female player to completely boycott women-only tournaments and matches, since the competition in those events is invariably much weaker than in male or open events. At any rate, her career fizzled a bit a decade later, and she retired in 2014 at 38.

The other great female chess player is China’s Hou Yifan [15]. Still only 25, Hou is currently ranked eighty-seventh in the world and peaked four years ago at fifty-ninth place, with a rating of 2686. Like Polgar, Hou eschews women’s events, but only after winning the women’s world championship title in 2010, a feat Polgar never stooped to accomplish. Despite being easily the best woman on the planet (Hou defeated Polgar in their only encounter in 2012), she has never been able to compete on even footing with the very best men. She has been a ratings wildcard in several top tournaments, and almost always performed [16] poorly [17]. Nonetheless, she continues to avoid women-only events, even to the point of resigning a 2017 tournament game in protest [18] after having been paired with women in seven of her nine previous games.

Despite the dearth of evidence supporting female-male equality in chess and the plethora of evidence against it,[7] [19] openly ascribing female inferiority to genetics still creeps into taboo territory. Chess people have been doing what they can to encourage female chess players [20] in the hope that, one day, inter-gender equality will be realized. The nurture argument remains strong with many, even in a field known for prodigies like Bobby Fischer, who famously had no chess nurturing at all as a young child, and became a world champion regardless. Thus it’s quite eye-opening when two studies appear within a short time which challenge common conceptions of female chess.

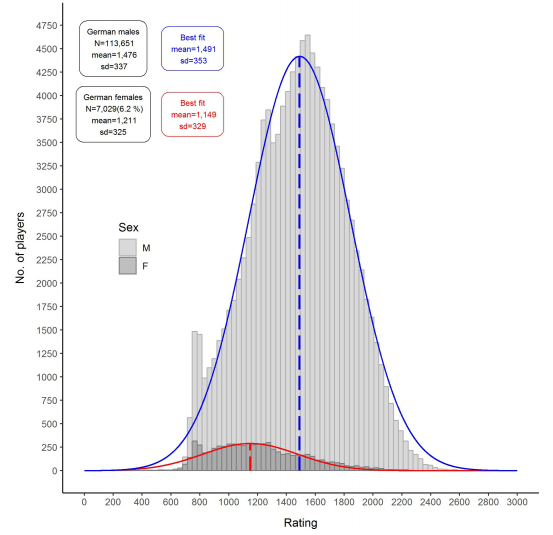

Bruno Wiesend has taken a step towards dismantling the nurture-over-nature argument with his recent study “Questioning Gender Studies on Chess [5].” In 2009, researchers Bilalic, Smallbone, McLeod, and Gobet offered the “participation rate hypothesis [6],” which posited that “96 % of the differences between females’ and males’ playing strengths could be attributed to the simple fact that more males than females were playing chess,” according to Wiesend. The researchers used a German database which contained the ratings of approximately 113,000 male players and 7,000 female players. They essentially grouped female and male ratings into the same population, and then claimed that ratings differences in the extremes resulted mostly from vastly different sample sizes and bell curve widths.

For this, Wiesend accuses them of putting the cart before the horse. They assumed a common distribution between male and female ratings before making their calculations, when in fact the male and female bell curve histograms were not symmetrical, and did not share a common distribution at all.

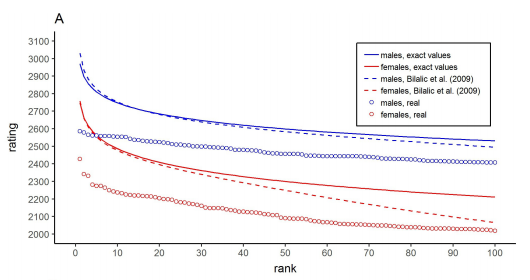

Wiesend also called into question how the researchers used “simple approximations” to calculate the expected ratings for the best females and males. In figure 2A below, he showed how the authors’ approximations and the exact values differed from the real values in the German database.

Wiesend (emphasis mine):

Fig. 2 A also shows that both the approximated and the exact values are unrealistic and far removed from the real values. For example, the real rating of the best German player was 2,586 points; Bilalic et al.’s (2009) approximation was 3,031 and the exact value 2,970. The crucial point is that the extremes of a normal distribution can only be calculated exactly, if it is perfectly normal. “Approximately normal” as the authors called it, is not good enough. This is best illustrated by the large free space between the male best-fit curve and the rightmost bins in the histogram in Fig. 1. There are no perfectly normal chess ratings in the real world. The approach used by Bilalic et al. (2009) to prove the participation rate hypothesis, was therefore inappropriate.

Wiesend performs more statistical analyses in his paper and comes to following conclusions, which many race and gender realists will find not only acceptable, but welcome:

- “The participation rate hypothesis cannot explain gender differences in chess.”

- “Stronger players are not only stronger because they play more tournament games, instead they play more games because they are stronger.”

- “Females and males are different species of chess players from the moment they start playing tournaments.”

Wiesand ends his paper by cautioning the reader that his findings do not necessarily amount to a knockout blow for nature over nurture. Currently, no one can scientifically prove male genetic superiority over female in chess. On the other hand, all the data we do have (scientific, statistical, anecdotal, historical) rebuts any attempt to prove female-male equality in chess. Therefore, the onus falls upon the egalitarians to find data that doesn’t do this. In the meantime, the most responsible thing to do is to assume that the nature argument is correct and that men simply make for better chess players.

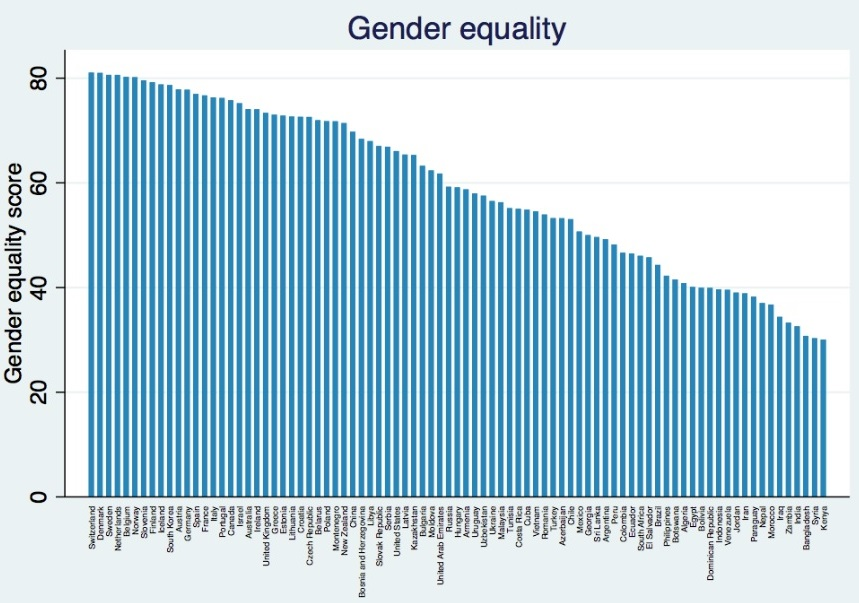

While Wiesand more or less tells us what we already know about gender differences, David Smerdon recently discovered something that may cut even deeper [7] into the belly of egalitarianism. He compared the rates of female chess participation in the eighty-five-most chess-active countries versus the United Nation’s Gender Equality Index, which ranks countries by their perceived oppression of women and girls. One would think that female chess participation would be greatest in countries ranking highest in the Gender Equality Index, but Smerdon discovered that the opposite is closer to the truth.

Here is a graph which lists the top chess-playing countries from greatest gender equality to least gender equality, according to the UN’s Gender Equality Score:

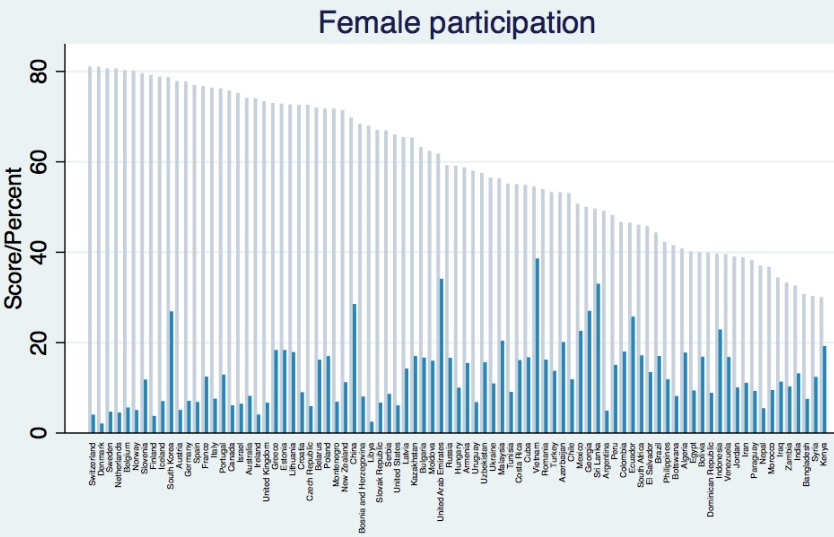

Not too many surprises here. Below is the same graph with vertical bars superimposed over it, which represent female chess participation (by percent):

While the correlation is not very strong, Smerdon has revealed that female participation in chess is generally greater in countries that are more patriarchal and (from a feminist standpoint at least) oppressive of women. Only one of the top thirty most gender-equal countries (South Korea) can be found in the top ten countries with the highest female participation rates.[8] [25] Not only this, but the six most gender-equal countries (Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden, Netherlands, Belgium, and Norway) all have lower female participation rates than the six least gender-equal countries (Kenya, Syria, Bangladesh, India, Zambia, and Iraq).

What to make of this? Smerdon himself offers a few possibilities, all of which are unsatisfactory:

- He cites a paper in the journal Science which he reports found that “the more that women have equal opportunities, the more they differ from men in their preferences. The story goes along the lines that if women somehow biologically prefer not to compete with men, then they will be most able to show this in countries where women have more freedom to choose.” While this may show how women tend to avoid chess in gender-equal countries, it implies that women are being compelled against their wishes to play chess in gender-unequal countries. Is this really the case in vastly different places like Vietnam, Sri Lanka, and Ecuador?

- “(W)omen are more likely to play chess in gender-unequal countries because it’s one of the few fields where they can actually compete with men, and be sure that the result is judged without discrimination (as opposed to, say, promotions in the workplace).” Nonsense. This assumes that women want to compete with men in the first place (which is belied by the data), and secondly, it implies that these women actually have a chance at beating men at chess, which they don’t. In terms of talent and ratings (as opposed to mere participation rates), men dominate chess in gender-unequal countries as much as they do in gender-equal countries.

- Since many gender-unequal countries are new to chess, they have a large proportion of young players, of which a notable proportion are girls. This may be true, but Smerdon himself states that even in gender-unequal countries, women tend to drop out of chess by their twenties and never return (a finding echoed by Wiesend), whereas men who drop out have a much greater rate of return once they reach their forties. While this may explain some of Smerdon’s findings (although China has been dominating women’s chess since the early 1990s and Georgia decades before that, so neither can be considered new to chess), it says nothing about why women tend to quit the game or why they fare poorly against men.

To anyone on the Dissident Right, the answer should be obvious. Men and women are different enough genetically that, despite the occasional Judit Polgar or Hou Yifan, there will always be an achievement gap between the sexes. Men are much more likely to be born with the character traits required to be competitive chess players. One needs, among other things, strong powers of concentration, spatial sense, a vast memory, logical ability, and a burning desire to win. These qualities have never been considered feminine, not because of what certain men do or say, but because most women are simply born without them. Science may not be able to prove this definitively today. But it will someday.

And now for the slippery slope. From here, it is only a brisk stroll away from pronouncing women naturally inferior to men in a whole host of technical and scientific fields. Such an outcome would render feminism completely irrelevant and dash many a woman’s hope of letting her gender achieve things for her that her skills certainly cannot. This would result in fewer women wielding real power in technical fields, fewer economically independent women, and an overall dampening of the political influence that women as a discrete demographic can have. Of course, the Left-wing power structure of today’s society will give its pointy eyeteeth to prevent that from happening. This is why such commonsense studies are considered “controversial.”

Then from there, we’re only a hop, skip, and a jump away from the ultimate taboo: proclaiming different races better or worse than each other, not only in chess but in anything. Indeed, the black impact on chess is more negligible than that of women. To date, there have been only three grandmasters of Sub-Saharan African descent (as opposed to thirty-seven women [26]). The first was Maurice Ashley, who was born in Jamaica and plays for the United States. His peak rating was 2504 in 2001. He’s mostly known these days for his first-rate chess commentating. The second was Pontus Carlsson, who currently has a rating of 2456 and is ranked seventeenth in his home country of Sweden. The third is the Zambian Amon Simutowe, whose current rating in 2449. Of course, these three never came close to cracking the world’s top one hundred. For those who care, The Chess Drum [27] is a Website run by an ethnocentric black who likes to celebrate black mediocrity in chess. His cognitive dissonance on his race’s manifest inferiority in his chosen field makes him both admirable and repulsive as a writer.

There have been quite a few top-level Hispanic chess players both historically and today, the most notable being J. R. Capablanca from Cuba, who was World Champion in the early twentieth century; Brazil’s Henrique Mecking, who was ranked third in the world in the late 1970s; and Cuba’s Leinier Dominguez Perez, who now plays for the US and is seventeenth in the world ratings. But many of these men, to quote Jared Taylor, look white to me.

Hopefully, these two studies will do much to red-pill people who pay any attention to chess. Bruno Wiesend’s study, while important and necessary, seems more a defensive measure against the Left. The Left attacks with nurture argument and the non-Left (I don’t want presume the author’s politics) deftly parries with evidence and argument. On the other hand, David Smerdon, whether he realized it or not, went on a screaming berserker attack on the Left and actually gained us some ground.

And everyone should be aware of this.

It’s not so much that women are inferior to men in chess. No, no. They also look up to men, and wish to emulate them and become more accomplished human beings when men boss them around more. Is there a better explanation for why Kenyan and Iraqi women play international chess at higher rates than women in Denmark and Sweden? Could this phenomenon then be transposed to race, namely to how blacks in America actually behaved better as minorities with less crime and illegitimacy and greater cultural achievements when whites were more racially assertive as the dominant demographic?

Could there be anything more ruinous to the Left than this?

Notes

[1] [28] Pronounced “fee-day,” FIDE is a French acronym standing for Fédération Internationale des Échecs.

[2] [29] As of May 2019, the highest-rated girl in the world has a rating of 2464, whereas the rating of the hundredth-rated boy is 2473.

[3] [30] Elo ratings represent the statistical analysis of a chess player’s strength at a given time boiled down to a single figure. A player’s rating fluctuates according to how well or poorly he performs against other rated players in official games. This often provides predictive power, with higher-rated players being favored to win against lower-rated ones. At the moment, there are only thirty-eight people with an Elo rating over 2700 [31]. Current world champion Magnus Carlsen [32] of Norway has a rating of 2861 at present, and, in 2014, achieved the stratospheric rating of 2882, which is the highest ever for a human. Stockfish, the strongest chess engine around today, has a Godlike rating of 3564 [33].

[4] [34] A record that has been broken dozens of times [35] since 1991, thanks in large part to the proliferation of electronic chess programs which play chess on superhuman levels.

[5] [36] Judit Polgar’s record against Kasparov is pretty dismal, though. According to chessgames.com [37], she has only one win and twelve losses against him, with four draws. And that one win came under rapid [38] and not classical [39] time controls.

[6] [40] In 1994, Polgar lost a game to Kasparov that many felt she should have won, since Kasparov had allegedly broken the rules. According to what became known as the “Touch-Move Controversy [41],” Kasparov had touched one piece but then moved another – a serious no-no in professional chess. At 18, Polgar was too intimidated by the circumstance to formally protest. Further, it remains debatable whether Kasparov’s initial move would have lost him the game.

[7] [42] According to Wiesand:

In the January 2019 international chess federation (FIDE) rating list, the best 100 males were, on average, 254 points stronger than the best 100 females. This situation has not changed during the last 20 years: In January 1999, the difference was 250 points and in January 2009, the males were 239 points stronger.

[8] [43] The top ten countries with the highest rates of female chess participation are (with their gender-equality rank in parentheses):

- Vietnam (52)

- United Arab Emirates (41)

- Sri Lanka (59)

- China (31)

- Georgia (58)

- South Korea (10)

- Ecuador (63)

- Indonesia (73)

- Mexico (57)

- Malaysia (48)

Spencer J. Quinn is a frequent contributor to Counter-Currents and the author of the novel White Like You [44].