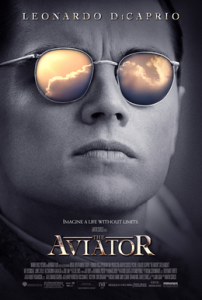

Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator

Posted By Trevor Lynch On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledMy favorite Martin Scorsese film is Gangs of New York (see my review here [2]), but his follow-up film, The Aviator (2004), is a close second and rises in my estimation with each viewing. The Aviator is an epic depiction of the career of Howard Hughes, spanning the years 1927 to 1947, from the creation of his WWI flying epic Hell’s Angels to the successful test flight of the Hercules transport plane, dubbed by his enemies the “Spruce Goose.”

In its feel, Scorsese’s depiction of a heroic industrialist battling philistines, nay-sayers, corrupt politicians, and unethical rivals is the closest thing we will ever get to a decent film adaptation of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead or Atlas Shrugged, and in some ways it is far more interesting than Rand’s stories because Hughes was real. He was, furthermore, more heroic than any Rand protagonist because he not only overcame the whole world but also a far more formidable adversary, namely his own mental illness.

Hughes inherited the Hughes Tool Company from his father, which he used to finance his work in two industries which centered around his personal obsessions: film and aviation. (He also invested his film and aviation profits in extensive real estate and hotel holdings.) Hughes directed two films, Hell’s Angels (1930) and The Outlaw (1943) and produced a number of others, first as an independent producer, then by acquiring a controlling interest in RKO. Hughes’ taste in film was unabashedly masculine (war and boobs). And although he was a playboy, he was conservative in his politics if not his morals and worked to purge RKO of Communists.

But above all else, Hughes was an aviator. He created Hughes Aircraft while filming Hell’s Angels. He set a number of aviation records; was intimately involved in the design, development, and testing of a number of airplanes; revolutionized commercial aviation; and survived four airplane crashes (two of which are depicted in the film).

Leonardo Di Caprio is wonderfully believable in his portrayal of Hughes as a stubborn visionary who combined technological mastery and shrewd business instincts with a strong aesthetic sensibility, although in truth his airplanes were more artful than his movies. Di Caprio is particularly brilliant in capturing Hughes’ mood swings from charismatic, boyish enthusiasm to obsessive-compulsive paranoia. Cate Blanchett won an Oscar for her role of Katherine Hepburn. Other solid performances are Kate Beckinsale as Ava Gardner, Alec Baldwin as Juan Trippe, and Alan Alda as Senator Owen Brewster.

One of my favorite parts of The Aviator is Hughes’ romance with Katherine Hepburn, especially their golf match (in gorgeous two-color Technicolor), her compassionate response to his mounting obsessive-compulsive disorder and paranoia, and his disastrous dinner with her rich, snobbish, and obnoxiously Left-wing family.

There’s a strong populist feel to The Aviator, for Hughes was a Texan who was constantly at odds with the Hollywood Jewish and Eastern liberal WASP establishments. Although Hughes inherited wealth like the Hepburns, he did not hold people who work for a living in contempt. When Hepburn finally left him, Hughes became increasingly unmoored from reality and consumed by his obsessions.

I also very much enjoyed Scorsese’s handling of the aviation sequences in the making of Hell’s Angels; the building, test-flight, and crash of the H1-Racer after setting a speed record; the building, test-flight, and crash of the XF-11 reconnaissance plane (Hughes called it his “Buck Rodgers” ship); and finally the test flight of the Hercules.

Scorsese used models, not computer animation, in these sequences, and the payoff in terms of realism is palpable. The use of Eugene Ormandy’s orchestration of Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D-Minor for the XF-11 sequence was an inspired choice. (The soundtrack contains original music by Howard Shore, which to my surprise made no impression on me, and a large number of well-chosen pieces of popular music from the period.)

Another excellent sequence is Hughes’ triumph over a Senator Owen Brewster and Juan Trippe of Pan Am, who cooked up legislation that would give Pan Am a monopoly on international air travel from the United States. Brewster also launched a Congressional investigation of Hughes, digging up embarrassing information and accusing him of defrauding the US government out of $56 million. Then Brewster offered to call off the hearings if Hughes would sell TWA to Pan Am. It was transparent blackmail.

Hughes refused, then retreated into a cocoon, holing up in a screening room for months, communicating only by tape recordings and intercom, peeing in bottles, etc. Hughes finally pulls himself together with the help of Ava Gardner (best lines: “I love what you’ve done with the place” and “Nothing’s clean, Howard. But we do our best anyway”). Yes, Hughes actually did things like this, though the sequence of events may have been altered for dramatic effect.

Hughes goes to Congress and in a fiery speech flays the hypocrisy of the charges against him. For instance, $800 million in aircraft were not delivered during the war because of research and development failures, but only Hughes was being investigated. Then he exposes Brewster’s real agenda: to cripple TWA because it threatened Pan Am with competition. It is thrilling drama. Alan Alda is brilliant in his portrayal of oily operator Senator Brewster.

The movie ends with the triumphant flight of the Hercules, the prototype of which was finished by Hughes at great expense, even though the war was over and the military had cancelled the project. It was a matter of personal pride for Hughes, and it was a magnificent engineering achievement.

At the afterparty, an ebullient Hughes declares that jet aircraft are the way of the future. Then his OCD takes over. He can’t stop repeating the phrase “the way of the future, the way of the future.” His business manager and chief engineer hustle him into isolation so he can regain control. Scorsese wisely ends the film here, with Hughes alone in the throes of his compulsions.

This was indeed “the way of the future” for Hughes. He spent his last 29 years in increasing seclusion, living in luxury hotel suites, moving from triumph to triumph building his business empire and vast fortune. Racked with chronic pain from the XF-11 crash, which nearly killed him, and increasingly consumed by OCD, Hughes apparently became addicted to painkillers. He died at the age of 70. His six-foot four-inch frame weighed only 96 pounds. He had apparently starved himself to death. The pitiful final triumph of an unbridled Faustian will.

The Aviator is a masterpiece, a work of tragic grandeur encompassing everything that made America both great and terrible, a biopic raised to the level of myth.