Historicizing the Historicists:

Notes on Leo Strauss’ “The Living Issues of German Postwar Philosophy,” Part 2

Posted By

Greg Johnson

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

4,535 words

Part 1 here [2]

The Intellectual Bankruptcy of the Present Age

Not only does Strauss claim that historicism is a healthy reaction to the intellectual bankruptcy of the modern world, in the next section of his essay, he also attributes this bankruptcy to non-historicist causes.

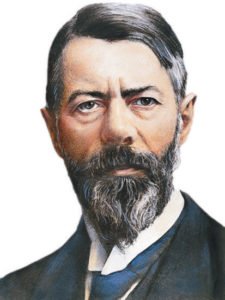

First, Strauss talks about Max Weber’s Learning and Science as Vocation. He specifically objects to Weber’s claim that reason cannot speak about the ultimate aims of life: being, nature, God, values, etc. Reason can only speak of means to ends. But our ultimate ends are matters of choice: arbitrary and subjective choice. If, however, reason cannot provide guidance to human life, then people will naturally turn to authority.

Then Strauss discusses Carl Schmitt’s The Concept of the Political, attributing the same sort of value relativism to it, even though it appears nowhere in the text.

Then Strauss devotes a paragraph to Ernst Jünger’s essay “On Pain,” which asserts that “in our period all faiths and ideals of earlier times have lost their force and evidence. Consequently, all standards with reference to which we can judge ourselves and others are no longer valid” (p. 128). This has more a flavor of Nietzsche’s “death of God” than a simple philosophical thesis about the groundlessness and relativity of values. Jünger’s solution is quite arbitrarily (of course) to assert the value of courage in the face of nihilism.

After this, Strauss turns his attention to religion, for in the face of nihilism God would seem a higher authority than the state. He mentions but does not name a “remarkable philosophic writer of predominantly theological interest [who] was fond of the fact that the very term ‘religion’ did not occur once in his work” (p. 128). He mentions in passing Karl Mannheim’s pitiful attempt to defend reason as a form of dialogical muddling-through, an attempt to synthesize views as opposed as religion and atheism without the ability to comment on their ultimate truth.

The return to God, however, is blocked by the fact that God is dead, i.e., we no longer believe in him: “Nietzsche’s statement that the greatest event in the recent history of Europe is the death of God was explicitly or implicitly adopted by a considerable number of writers (Spengler, Scheler, Hartmann, Heidegger). According to that view, the present age is the first radically atheistic epoch in the history of mankind” (p. 130). Whereas the atheism of the 19th century replaced God with a deified humanity, the new atheism entirely dispensed with religion and religion-substitutes.

At this point, it was quite natural for people to start thinking of radical alternatives to the present. As Strauss drily remarks, “It was hard not to see that the question of the existence or non-existence of a personal God, Creator of Heaven and Earth, was a serious question, more serious even than the question of the right method of the social sciences” (p. 130). But it was also equally clear that there was no way to deal seriously with this question within the post-Kantian intellectual horizon in which reason is declared impotent to deal with such questions.

Furthermore, Strauss adds, “The urgency of [supplying] a convincing, generally valid moral teaching, of a moral teaching of evident political relevance, was clearly felt” (p. 131). According to Strauss, “Such a moral teaching seemed to be discernible in the natural law doctrines of the 17th and 18th centuries rather than in later teaching[s]” (p. 131).

The Overcoming of Historicism

In Strauss’s narrative, the initial attempts to find a new intellectual horizon only point back to pre-Kantian speculative metaphysics and the natural law philosophers of the 17th and 18th centuries. It is not clear if Strauss is describing his own intellectual journey or someone else’s. It would be interesting to know if there was a “back to Rationalism” movement in Weimar academia.

. . . the rationalism posterior to historicism returned from Turgot and his pupils to Montesquieu or the 17th century philosophers. For that new rationalism was engaged in the quest for eternal truths and eternal standards, and it clearly realized that eternal truths and eternal standards are indifferent in themselves to any theory as to the sequence in which they are discovered or put into practice. “History” became again the realm of chance; i.e., “history” ceased to be a realm of its own, a field in the way in which nature is said to be a field. Historicism was about to be overcome definitely. (p. 132)

Yet Strauss has still not explained how the specifically historicist drive to overcome the bankruptcy of the present and reconnect with pre-Kantian philosophy leads to the overcoming of historicism. Is Strauss’s point merely that pre-historicist speculative and natural law philosophy is what the historicists really wanted all along, such that, once they get it, historicism will simply be dismissed like a taxi once they have reached their destination?

I should note also that historicism cannot be “overcome” merely by demoting history to the realm of “chance.” From a Heideggerian point of view, history is “inside” us, in our language and other meaningful social practices that make thought possible to begin with. “History” was also “inside” Montesquieu and every other pre-historicist philosopher as their operative presuppositions, even though they did not know it, even though they dismissed history as the realm of the accidental.

Strauss goes on to explain more fully how the return to pre-Kantian philosophy is an overcoming of historicism:

The view that truth is eternal and that there are eternal standards, was contradicted by historical consciousness, i.e., by the opinion that all “truths” and standards are necessarily relative to a given historical situation, and that, consequently, a mature philosophy can raise no higher claim than that to express the spirit of the period to which it belongs. (p. 132)

I do not think that it follows from historicism that a philosophy is merely an expression of its time and place. I am a kind of Heideggerian historicist. But I think that historicism is true for all times and places, even times and places when historicism never occurred to people. Beyond that, I think that certain arguments offered by ancient and medieval philosophers, in radically different languages and cultures, remain more convincing to this day than rival views.

For instance, I find Plato’s tripartite psychology, Aristotle’s account of the virtues, Anselm’s ontological argument, and Maimonides’ argument (adapting Aristotle) that there is a being that exists necessarily to be wholly convincing. These views could, of course, be refuted if someone came up with better arguments. But it is no refutation to say that these ideas were merely a product of their times that we don’t need to take seriously in the current year.

Having tried to assimilate history to the concept of accident or chance (versus eternity), Strauss then tries to assimilate it to opinion (versus truth):

Now, historical consciousness is not a revelation; it claims to be demonstrably superior to the unhistorical earlier view. But what does the historicist really prove? In the best case, that all attempts hitherto made by man to discover the truth about the universe, about God, about the right aim of human life, have not led to a generally accepted doctrine. (p. 132)

Here Strauss claims that historicists argue that philosophers have not discovered any objective truths because philosophers disagree with one another. But note that this is not really a historicist argument at all. It is merely a skeptical argument. It is, moreover, a specious argument, for as Strauss correctly points out, differences of opinion do not imply that truth is impossible:

Which is clearly not a proof that the question of the truth about the universe, about God, about the right aim of human life is a meaningless question. The historicist may have proved that in spite of all the efforts made by the greatest men, we do not know the truth. But what does this mean more than that philosophy, quest for truth, is as necessary as ever? What else does it mean but that no man, and still less no sum of men, is wise, σοφός, but only, in the best case, φιλόσοφος? Historicism refutes all systems of philosophy—by doing this, it does the cause of philosophy the greatest service: for a system of philosophy, a system of quest for truth, is non-sense. In other words, historicism mistakes the unavoidable fate of all philosophers who, being men, are apt to err, for a refutation of the intention of philosophy. Historicism is in the best case a proof of our ignorance—of which we are aware without historicism—but by not deriving from the insight into our ignorance the urge to seek for knowledge, it betrays a lamentable or ridiculous self-complacency; it shows that it is just one dogmatism among the many dogmatisms which it may have debunked. (pp. 132–33)

Again, historicism is not the same thing as skepticism. Skepticism wishes to collapse the distinction between knowledge and opinion, to reduce all putative knowledge to mere opinions, and to declare the quest for truth to be impossible. A phenomenological historicism like Heidegger’s or Gadamer’s is not about eliminating the distinction between truth or opinion. It does not deny that we can pursue truth. It simply tries to understand what makes both opinion and truth possible.

From a Heideggerian point of view, it is certainly possible for arguments offered by Plato and Aristotle to repel all critics and remain compelling to this day. But that does not require us to interpret this in terms classical metaphysical categories like eternal necessary truths vs. mere opinion or mere historical contingencies.

Strauss goes on to write, “Philosophy in the original meaning of the word presupposes the liberation from historicism” (p. 133). He distinguishes liberation from refutation. To be liberated from historicism requires an understanding of “the ultimate motives” of historicism, which for Strauss is the desire to escape from the intellectual bankruptcy of the present day. Strauss continues:

The liberation from historicism requires that historical consciousness be seen to be, not a self-evident premise, but a problem. And it necessarily is a historical problem. For historical consciousness is an opinion, or a set of opinions, which occurs only in a certain period. Historical consciousness is, to use the language of that consciousness, itself a historical phenomenon, a phenomenon which has come into being and which, therefore, is bound to pass away again. Historical consciousness will be superseded by something else.

The historicist would answer: the only thing by which historical consciousness can be superseded is the new barbarism. As if historicism had not paved the way to that new barbarism. Historical consciousness is not such an impressive thing that something superior to it should be inconceivable. (p. 133).

Historicism is, again, the product of cultural decadence. But if cultural decadence can pass away, then so can historicism. Historicists themselves believe this is possible. Historical consciousness is a form of self-consciousness that emerges in relatively refined cultures. Barbarians, however, are crude and unreflective. Thus if a decadent culture were to collapse into barbarism, historicism would disappear.

Strauss does not attribute this argument to anyone in particular, but it is found in Giambattista Vico’s philosophy of history. Vico argues that decadent societies are afflicted with what he calls the “barbarism of reflection,” which would include historical consciousness. The barbarism of reflection can, however, lead to the collapse of civilization, which will return to survivors to a more naïve but healthy consciousness that Vico dubs the “barbarism of sense.”[1] [3] Strauss did not start reading Vico until the early 1960s. (He gave a seminar on Vico’s New Science in 1963.) But he had heard about Vico’s ideas before then from secondary literature.

Strauss dismisses this idea with a bit of snarky rhetoric. He clearly wants to believe that a post-historicist society can be more civilized than a historicist one. But the historicists would respond that one can only arrive at a post-historical form of consciousness by becoming naïve. A Heideggerian, for instance, would argue that Plato and Aristotle were simply naïve about how their own thinking was both enabled and disabled by historical conditions like their language and cultural heritage.

One cannot, however, simply will oneself to be naïve again. The only way a culture, like an individual, could lose its self-consciousness is through an experience that is traumatic enough to be literally stultifying, a blow to the head that would cause amnesia. Of course, one could accept that one cannot make oneself naïve but still aim to impose naïveté on future generations, to narrow their horizons by imposing a stultifying education upon them.

Strauss continues:

What was required was that history should be applied to itself. Historical consciousness is itself the product of a historical process, of a process which is barely known and certainly never adequately, i.e. critically studied. I.e.: historical consciousness is the product of a blind process. We certainly ought not to accept the result of a blind process on trust. By bringing that process to light, we free ourselves from the power of its result. We become again, what we cannot be before, natural philosophers, i.e., philosophers who approach the natural, the basic and original question of philosophy in a natural, an adequate way. (p. 133).

Strauss is surely right to call for a reflexive historicism. Historicism is a form of self-consciousness. It seeks to disclose the historical conditions of consciousness. So naturally, it should inquire into its own historical conditions. But Strauss’s conclusion—“By bringing that process to light, we free ourselves from the power of its result”—does not follow at all. For what if historical self-consciousness is grounded in human nature and emerges necessarily in the spiritual development and maturation of mankind? Historical consciousness may be like puberty. It happens at a particular time, but that fact alone does not imply that it is a historical contingency not a natural necessity. If historical consciousness is a necessary part of our spiritual maturation, turning historical self-consciousness back on itself would perfect it, not destroy it.

A Return to Plato & Aristotle?

Strauss ends his essay by speaking about the importance of the most radical historicists of all, Heidegger and Nietzsche, to his project of overcoming historicism and returning to classical philosophy. Strauss also praises Heidegger’s teacher Husserl.

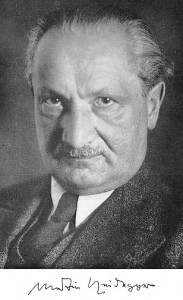

In 1922, after completing his Ph.D. in Hamburg, Strauss went to the University of Freiburg to study with Husserl. He also attended Heidegger’s lectures from time to time. He did not get much from either thinker. He was, however, quite impressed by a lecture by Heidegger on the beginning of Aristotle’s Metaphysics,[2] [5] recalling that “I had never heard nor seen such a thing—such a thorough and intensive interpretation of a philosophic text.” Strauss told Franz Rosenzweig, that “compared to Heidegger, Max Weber, till then regarded by me as the incarnation of the spirit of science and scholarship, was an orphan child.”[3] [6] Thus when Strauss speaks of “the younger generation in Germany,” he is speaking of himself and few others who attended Heidegger’s lectures in Freiburg:

Modern philosophy has come into being as a refutation of traditional philosophy, i.e., of the Aristotelian philosophy. Have the founders of modern philosophy really refuted Aristotle? Have they ever understood him? . . . He cannot have been refuted, if he has not been understood: And this was perhaps the most profound impression which the younger generation experienced in Germany during the period in question: under the guidance of Heidegger, people came to see that Aristotle and Plato had not been understood. Heidegger’s interpretation of Aristotle was an achievement with which I cannot compare any other intellectual phenomenon which has emerged in Germany after the war. Heidegger made it clear, not by assertions, but by concrete analyses—the work of an enormous concentration and diligence—that Plato and Aristotle have not been understood by the modern philosophers . . .

Then Strauss explains Heidegger’s account of precisely how modern interpreters have failed to understand Plato and Aristotle. Recall that one of the arguments Strauss cites for the necessity of historicism in our times is to combat the complacency of the progressivist mentality, which assures any college undergraduate that he is superior to Plato and Aristotle simply because he lives in the current year. Recall also that I likened Strauss’s description of the historicist critique of progressivist complacency to Heidegger and Husserl’s attempts to criticize modern thought by dismantling it and returning to the experiences that gave rise to it. Here is Strauss’s description of phenomenological historicism in action:

[Modern interpreters] read their own opinions into the works of Plato and Aristotle; they did not read them with the necessary zeal to know what Plato and Aristotle really meant, which phenomena Plato and Aristotle had in mind when talking of whatever they were talking [about]. And as regards the classical scholars, their interpretations too are utterly dependent on modern philosophy, since the way in which they translate, i.e., understand, the terms of Plato and Aristotle is determined by the influence on their mind of modern philosophy. For even a classical scholar is a modern man, and therefore under the spell of modern biases: and an adequate understanding of a pre-modern text requires, not merely knowledge of language and antiquities and the secrets of criticism, but also a constant reflection on the specifically modern assumptions which might prevent us from understanding pre-modern thought, if we are not constantly on our guard. (pp. 134–35)

Heidegger articulated the unstated presuppositions of Aristotle’s interpreters that made them unable to actually understand his writings. Then, by dismantling this tradition and reinterpreting Aristotle’s texts with an eye to the actual experiences he was trying to articulate, Heidegger made it possible to understand Aristotle in a much deeper way.

Note that in Strauss’s argument so far, a complacent progressivist historicism has been overcome by a more radical form of historicism. Strauss, however, goes much further. He claims that Heidegger’s dismantling of the philosophical tradition overcomes historicism as such and makes it possible to return to classical philosophy: “If Plato and Aristotle are not understood and consequently not refuted, return to Plato and Aristotle is an open possibility” (p. 135). This return allows us to “become again, what we cannot be before, natural philosophers, i.e., philosophers who approach the natural, the basic and original question of philosophy in a natural, an adequate way” (p. 133). Or: “A return to reason which implies or presupposes a critical analysis of the genesis of historical consciousness, necessarily is a return to reason as reason was understood in pre-modern times” (p. 133).

Strauss makes it clear by referring to the “approach to the natural” and the “basic and original question of philosophy” that he is not necessarily envisioning a return to the specific doctrines of Plato and Aristotle. A bit later, he writes: “whatever may be the final result of our studying Plato and Aristotle, whether or how far we can adhere ultimately to their analyses in all respects or not—what is decisively important is that we first learn to grasp their intention and then that their results be discussed” (p. 137). For Strauss the essential matter is to return to the questions that concerned Plato and Aristotle and their way of grappling with them. Philosophy is the love—the pursuit—of wisdom, not necessarily its possession.

Naïve vs. Knowing Returns

[7]But can we really “return” to Plato and Aristotle? Can we really “return” to reason and nature as understood by the Ancients? It depends on how you envision the return: is it a naïve return or a knowing return? Strauss mentions a movement in Weimar academia called the “third humanism”:

[7]But can we really “return” to Plato and Aristotle? Can we really “return” to reason and nature as understood by the Ancients? It depends on how you envision the return: is it a naïve return or a knowing return? Strauss mentions a movement in Weimar academia called the “third humanism”:

“Third humanism” would be a movement which continues in a most radical way the second humanism, the humanism of the German classics, of Schiller, e.g., who in his essay On Naïve and Sentimental Poetry had described the relation of the moderns to the ancients in these terms: the Greeks were nature, whereas for modern man, nature, being natural, is only an ought, an ideal; modern man has a longing for what was real in Greece. (p. 135)

Although Strauss does not spell it out, a third humanism would fulfill the longing of the second humanism by returning to the real. The Greeks enjoyed the immediate presence of the world. This presence was taken from us by other-worldly metaphysics and modern skepticism. The natural reaction was a longing for regained presence. A third humanism would satisfy that longing.

But you can’t really go back to the beginning. Instead, you arrive at a third position.

In Hegel’s terms, Greek culture is characterized by “being in itself”—unmediated, unreflective presence. This immediacy is lost when we become reflective, in Hegel’s terms “being for itself,” and for Hegel and Nietzsche, reflection is coeval with Greek philosophy, certainly from Socrates forward. But when one realizes that reflection alone is not enough and seeks a return to immediacy, one does not arrive at being in itself again. One instead arrives at a third position, “being-in-and-for-itself,” a knowing return to presence, a mediated presence endowed with new meaning.

One could make the same argument in Husserl’s language. The Greeks enjoyed the vivid presence of beings. Their intentionality is “filled” by the presence of beings. We moderns are alienated from reality. Our intentional acts are still directed toward the world, but they are “empty.” Our thoughts are directed to beings in their absence. But one does not simply return to presence. Instead, one arrives at a third position, a synthesis in which one’s empty intentions are fulfilled by the presence of beings, endowing present beings with new meanings.

Heidegger shows that it is definitely possible to clear away false interpretations and hidden modern assumptions that cut us off from understanding the Ancients. But this is not a simple “return” to the Ancients, for we know something that they didn’t: we are aware of how language and culture operate in the background to both enable and disable our awareness of the world. A simple return to Ancient philosophy would require that we forget this and become naïve about reason’s indebtedness to its historical conditions. This could come about through a collapse into barbarism. But one can’t will oneself to be naïve, although one can pull the wool over other people’s eyes.

Strauss characterizes Heidegger’s knowing return to Aristotle as a simple return to philosophy as the Ancients understood it. This is false, but it does not change the substance of Heidegger’s readings or their effect, which was to bring Plato and Aristotle—as well as the questions that moved them and the way they pursued them—alive again for a new generation of readers. There is no incompatibility between Heidegger’s understanding of human finitude and philosophy as the pursuit of wisdom.

Strauss concludes with a paragraph on Nietzsche. For Strauss, Nietzsche’s primary concern was with philosophy, understood in contradistinction to both common opinion and consoling dogmas like providence or progressivism, all of which Strauss likens to the “cave” of Plato’s Republic. Thus Nietzsche is “against ‘history,’ against the belief that ‘history’ can decide any question, that progress can ever make superfluous the discussion of the primary questions, against the belief that history, that indeed any human things, are the elementary subject of philosophy”—in short, Nietzsche rejects progressivist historicism.

But Nietzsche rejects this form of historicism from an even more radically historicist point of view. Strauss himself mentions that it was against historicism and other cave doctrines that Nietzsche “reasserted hypothetically the doctrine of eternal return,” which teaches that the only semblance of eternity is the chaos of radical historical contingency circling back on itself. Furthermore, according to Strauss, Nietzsche advanced this radical historicist doctrine “to drive home that the elementary, the natural subject of philosophy still is, and always will be, as it had been for the Greeks: the κόσμος, the world” (p. 138).

Strauss also emphasizes that Nietzsche’s conception of philosophy is first and foremost about grappling with “elementary problems” (p. 137) and “the discussion of the primary questions” (p. 138), not the various more or less adequate answers people might offer to them. This is of course how Strauss describes the return to Platonic and Aristotelian philosophy. But in Nietzsche’s case, this return is completely consistent with radical historicism, whereas Strauss claims that a return to Plato and Aristotle is equivalent to the rejection of historicism as such.

Concluding Reflections

Strauss has a pattern. He both attacks historicism and returns to Ancient philosophy from the point of view of the even more radical historicisms of Nietzsche and Heidegger. But he claims, without argument, that the return to the Ancients is equivalent to the overcoming of historicism as such.

Strauss either knew what he was doing or he didn’t. Strauss did say that he attended Heidegger’s 1922 lectures “without understanding a word,” except for “one occasion: when he interpreted the beginning of the Metaphysics.”[4] [8] But Being and Time was published in 1927, and by 1940, Strauss surely understood a lot more of Heidegger’s work.

Beyond that, even if Strauss really was mistaken about Heidegger, is it really likely he would make the very same mistake about Nietzsche, a much clearer writer whom he had been reading for much longer? In a letter to Karl Löwith, Strauss claimed that, “Nietzsche so dominated and charmed me between my 22nd and 30th years [1920–1928] that I literally believed everything I understood of him.”[5] [9] So I am inclined to think that Strauss knew what he was doing.

But if Strauss knew there was a problem with his argument, why offer it? Strauss regarded Nietzsche and Heidegger as dangerous thinkers. Yes, they’d had a liberating effect on his mind. But he thought their ideas were bad for the general public. For instance, Canadian conservative political thinker George Grant reported that Strauss advised him not to include Nietzsche in a series of popular radio lectures but instead talk about his “epigones” Freud and Weber.[6] [10] He probably would have given similar advice about Heidegger.

So perhaps Strauss had a dual teaching about historicism. For the careless majority, he offers the false view that historicism enables us to return to Ancient philosophy as the Ancients understood it, thus historicism as such is overcome. The careful minority, however, know that things actually aren’t that simple.

Of course, offering a deceptive dual teaching isn’t exactly beyond Strauss.[7] [11] But for now, it remains a hypothesis. After all, “The Living Issues of German Postwar Philosophy,” is the unpolished and unpublished manuscript of a lecture. To test this hypothesis, we need to examine Strauss’s polished published writings on historicism, which will be the topics of future essays.

Notes

[1] [12] Giambattista Vico, The New Science, third edition, no. 1106. In The New Science of Giambattista Vico, revised translation of the third edition, Thomas Goddard Bergin and Max Harold Fisch (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1968), p. 424.

[2] [13] Heidegger’s lecture course has now been published as Martin Heidegger, Phänomenologische Interpretationen ausgewählter Abhandlungen des Aristoteles zur Ontologie und Logik, Gesamtausgabe, vol. 62, Günther Neumann (Frankfurt am Main: Vittorio Klostermann, 2005).

[3] [14] Jacob Klein and Leo Strauss, “A Giving of Accounts,” The College, April 1970, p. 3.

[4] [15] “A Giving of Accounts,” p. 3.

[5] [16] Correspondence of Karl Löwith and Leo Strauss, trans. George Elliot Tucker, Independent Journal of Philosophy 5/6 (1988): 177–92, p. 183.

[6] [17] Quoted in Ronald Beiner, Dangerous Minds: Nietzsche, Heidegger, and the Return of the Far Right (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018), p. 61.

[7] [18] Greg Johnson, “Strauss on Persecution and the Art of Writing,” Counter-Currents, January 3, 2013.