Our Marx, Only Better:

Vico & Modern Anti-Liberalism

Posted By

Greg Johnson

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

5,481 words

Author’s Note:

This is the transcript by V.S. of my speech “Vico and Modern Anti-Liberalism,” given at The London Forum on Saturday, September 27, 2014. I have heavily edited it, rewriting it in places. I want to thank Jez Turner and The London Forum team for a memorable event.

Today I’m going to talk about a topic that’s somewhat esoteric. I chose this topic because I was fond of Jonathan Bowden, and I understood that he could get people together to listen to a lecture on Heidegger or Robinson Jeffers or Maurice Cowling. So I thought, I’d like to give a lecture on a little-known thinker who I think is very important for our cause and our interests. His name is Giovanni Battista Vico. He was an Italian philosopher.

It’s an indication of how little went on in the world of Italian philosophy between the Renaissance and the 20th century that most people think Vico was a Renaissance figure, but actually he was born in 1668, died in 1744, and most of his writings were published in the early 18th century. He is a figure from the Enlightenment, and he’s also the first and most fundamental critic of the Enlightenment.

Since we here are interested in a critical appropriation of the Enlightenment, it behooves us to look at the first counter-Enlightenment thinker, and that was Vico. He was a counter-Enlightenment thinker before the Enlightenment was even really up and running. He had already figured out the bugs and written it all down, and he has something to offer us today.

I have been asking myself for years why so few people on the New Right talk about Vico, then it occurred to me that I had not yet given them an introduction. So, I decided to take it upon myself to introduce the New Right to Giambattista Vico.

Vico is sometimes mentioned in footnotes. He gets a few lines in potted histories of Western philosophy as the inventor of the philosophy of history or the philosophy of culture. His goal was to create a universal science of history and culture, which he summarized in his magnum opus the New Science. The New Science is an extension of the Enlightenment. It’s an extension of modernity. It’s an extension of the use of reason to understand society, to understand human nature. Vico belongs to the Enlightenment in the sense that he uses critical reason. He’s extending it from the natural sciences, where it was flourishing with Newton and Galileo, into the human realm. Yet, once he extended natural science into the humanities, he arrived at political conclusions that were diametrically opposed to the liberal progressive policies of the rest of the Enlightenment. So, he is the first counter-Enlightenment thinker, and yet he is a thinker of the Enlightenment.

Vico makes it possible to give a rational defense of man’s basic irrationality. He gives a non-religious defense of religion. He gives a non-traditional defense of tradition, an unconventional defense of convention. He’s a non-historical defender of historical life, particularity, and identity.

Vico argued that there are three fundamental institutions of society: religion, family, and the burial of the dead. But by the burial of the dead he meant something more than mere inhumation. He meant the sacralization of a particular piece of ground and therefore the origin of settled existence, localism as opposed to nomadism. He also argued for a cyclical theory of history.

Universally, the Left is about progress. The Enlightenment was about progress. The very concept of enlightenment is a process of progressing from darkness, superstition, tradition, religion, and so forth to reason. There is an onward and upward trajectory, a narrative of forward motion. The Left draws upon this pre-existing historical narrative to suggest the next step. It’s never enough. We can always progress more. We can always intensify the basic premises of modernity, the basic premises of egalitarianism.

On the Right, we tend to be skeptical of progress, and many of us are enamored of the idea of the cyclical nature of history. Now, both the cyclical idea of history and the progressive idea of history have roots in religion and myth, but in the 18th and 19th centuries the thinkers of the Enlightenment and thinkers like Marx tried to give a rational, scientific foundation for the idea of progress. They were not particularly successful, but they made strong efforts, and they convinced a lot people that indeed progress is baked into the modern world, and society will continue to progress in the direction of greater human freedom.

Based on Hegel and his interpreter Alexandre Kojève, Francis Fukuyama argued that when Communism collapsed history had ended with the triumph of liberal democracy. These ideas are very powerful to this day. Leftists try to give some kind of foundation for progressivism in history and human nature, whereas we on the New Right, broadly speaking, love to talk about the cycles of time. If you hear “Kali Yuga,” more than 90% of the time you’re dealing with somebody who’s plugged into the New Right. We’re virtually the only ones who talk about it today, outside of India.

I use this terminology all the time. I find myths and images to be very powerful ways of organizing and communicating ideas. But if you actually go into the details of what the Traditionalists say about the Golden Age and the decline therefrom, a lot of it is patently untrue. The image of the Golden Age that you get from traditional Hinduism or from Hellenists is of a time of what Vico called “abstruse and recondite wisdom.” What does that mean? Basically, being a philosopher: being mentally highly evolved and intuitively in contact with objective truths of nature.

Vico, by contrast, maintained that early man was like children are today: rude and crude and barbarous and dominated by his senses and his imagination. It’s only very much later in history that we arrive at abstract and recondite ideas, which are then projected backward on the Golden Age. Vico is criticizing a kind of Traditionalism. That’s one of his enemies in the New Science.

The other position that Vico is criticizing is Epicureanism, specifically the Epicurean idea of the beginning of history. Like Vico, the Epicureans believed that early man was rude and crude and primitive and barbarous. Their idea of early man and the evolution of man is actually extremely consistent with another faction within the New Right, those who are interested in biological evolution, the people who are interested in sociobiology, ethology, evolutionary psychology, and so forth—the materialist crowd. The Epicureans are the original evolutionary materialists. As we shall see, however, the Epicureans held that the beginning of history is more of a fall for man, whereas for Vico it is a rise.

Vico criticizes the Traditionalists of his time, but he maintains their cyclical view of history, their focus on religion, their interest in religion, arts, and humanities, and their social conservatism. Vico criticizes the materialists of his time, the Epicureans, but he maintains their essentially naturalistic hard-science approach to understanding man. He tries to come up with a synthesis of a Traditionalistic, cyclical view of history, social conservatism, and a critique of the Enlightenment that is also consistent with what is known about man’s real evolution, our prehistory and our history.

What Vico did in the 18th century is offer a synthesis that the New Right today dearly needs. Because I know people who, within the space of a single conversation—I include myself in this—will move from talking about what Evola says about the Golden Age, decline, the cyclical nature of history, the regression of the castes, and all that to what Philippe Rushton had to say about genetic similarity theory.

Someday somebody’s going to call me on it and say, “Wait a second here. These two worldviews are completely inconsistent. Evola believed that man in the Golden Age was a highly advanced being who devolved, and the whole evolutionary approach believes just the opposite. How do you reconcile these two things?”

A lot of us carry around unreconciled ideas, and Vico is important for the New Right because he offers a way of reconciling the two. So, let me go into a little bit of detail about how he does that.

The Traditionalists in Vico’s time were Plato and the Neo-Platonists. When they looked back at Homer and Hesiod and other early Greek writers, they projected the idea of a Golden Age as an age of abstract wisdom where man was intuitively in touch with deep truths, and after the Golden Age, man declines. He declines into a world where opinion rather than truth reigns, where nature is no longer a guide, but rather conventions, customs, and culture spring up. Culture consists of conventions. Nature is the same wherever you go, but conventions change. Nature is pretty much the same in Wales as it is just across the border in England, but Welsh and English are very different systems of conventions. Languages are conventions, and people who are naturally very similar genetically, who live in similar landscapes, similar environments, even have similar institutions can have radically different conventions like different languages. Nature is always the same across the board. Conventions change from time to time and place to place.

The Platonists looked upon the decline from the Golden Age into the later ages as a decline from the reign of truth—the Age of Truth is what the Hindus call the Golden Age—to living at greater and greater remove from the truth, living in terms of conventions and customs and illusions. It’s entering what Plato called “the cave” where you’re just looking at opinions rather than the truth. So, the Platonists see history as a fall, as a decline. It’s a horrible, ghastly mistake that needs to be erased. It’s something from which we need to be redeemed.

The Epicureans, the early materialists, also looked upon the beginning of history as something of a fall, but they had a very different view of man. They believed that man was a simple creature without intellect who is simply driven by his material desires: pleasure and pain. Now, if you just limit yourself to natural desires, it’s pretty easy to satisfy them. You need food and shelter and a little bit of companionship. But when you leave the state of nature and enter into society, we acquire artificial desires. We’re taught to desire things that we don’t really need, and as Eric Hoffer said, “You can never get enough of what you don’t really need.”

So, the emergence into history is the emergence of the rat race, where people are running themselves ragged to satisfy desires that are entirely artificial, and that is a source of misery. So these early materialists, the Epicureans, looked upon the beginning of history as a fall, as a source of alienation and suffering.

The common denominator between both the Traditionalists of Vico’s time and the materialists is they could not accept historical life as good. They both regarded it as a fall, either the fall of the philosopher into the realm of opinion or the fall of the happy brute into the realm of convention and the rat race. They couldn’t come up with a defense of what we’re interested in: namely, the plurality of different historical communities, our different cultures, our different ways of life. They couldn’t defend any identity other than natural identity, either the natural identity of the man who is totally determined by objective truth, which is true for everyone, or the loping, primal, ape-like creature who is totally determined by his natural needs, which are, again, the same. Natural man, whether he’s conceived of as an ape or as a kind of semi-divine being, doesn’t need and can’t even understand the necessity of having four different languages, or five, or millions of them. None of that makes sense. Nature is one. Culture is many, and that’s a problem.

Culture, therefore, by this account, is a mistake, and this is why Epicureanism had radical political implications. Back to nature is its basic message. Our happiness lies in nature. If we go back to nature, we have to slough off culture, we have to slough off differences, and we have to slough off our identities.

Now, within the New Right, we have our back-to-nature types, but they are also very attached to their cultural identities and folkways. We do, however, have a contingent of evolutionary psychologists and sociobiologists who seek to explain culture in terms of biology. For instance, Geoffrey Miller has a book called Spent which is about consumerism and luxury. It’s about the stuff that we don’t really need. He tries to come up with a biological explanation for it, and he says buying things you don’t really need is a form of signaling fitness to potential mates. So, he’s trying to reduce that element of culture into basic biological needs for reproduction. Why? Because there’s just a discomfort with the realm of culture as such, and if you can’t reduce it down to nature, they regard it as irrational, and they either want to ignore it or get rid of the irrationality of culture.

Vico is a conservative, and that means he’s trying to come up with a defense of historical life, a defense of culture, a defense of particular identities. Vico says there really is something golden about the Golden Age. But what was golden about it is not wisdom in the abstract sense. Instead, what is golden about the earliest phase of history is man’s vitality and imagination.

Early man was not smart or cultured, but he was vital; he was imaginative. He was a vital savage. He was ruled by his senses and his passions, but he also had a powerful imagination. Vico stressed that all human beings have the same basic nature and also face the same necessities of life. His view was that these crude beings with their powerful imaginations and passions will spontaneously generate culture when they encounter the necessities of life. On this account, culture is not a fall from a primal state of perfection that has to be reversed or redeemed in some way. For Vico, the development of civilization is a process of self-actualization, not just self-alienation.

The animal man is alienated in culture. We have all kinds of rules for governing the satisfaction of our bodily needs. That puts limits on us as animals. But Vico argued that those limitations are more than made up for by the fact that man has a social nature and an intellectual nature. The process of developing civilization actualizes our social and intellectual nature, which slumbers in a primitive state.

Vico calls his account of history a “rational civil theology of divine Providence.” Now, that’s a big mouthful, but what’s he saying? He’s saying there’s a providential order to history, and he’s very careful to say that he’s not talking about providence in the Biblical sense. He’s not talking about sacred history. He’s not talking about the Bible, because of course that’s a linear view of history, and he’s offering a cyclical one.

In Naples where Vico lived, an institution called the Holy Inquisition had been set up by the Spanish. They looked askance at people who were offering radically different alternative viewpoints to what the Church taught, so Vico was very careful. He said that he’s only talking about the Gentile nations, not about sacred history. But he said that within the history of the nations, the Gentiles, there is a kind of providence at work. It’s not the providence of the Biblical God, but it’s a process of man’s self-actualization that justifies history.

History is not merely a fall, but a step up, toward actualizing powers that cannot be actualized in the state of nature. Thus we don’t have to look upon culture as something that merely does violence to our nature. It’s something that perfects our nature as well. It does violence to our animal nature. It perfects the distinctly human aspects of our nature.

I now wish to discuss Vico’s primal institutions and how they come about. I also wish to discuss his scientific analysis of what underlies the cyclical view of history. Again, it’s desirable for us to stop using this cyclical view of history as merely a myth or an image but actually find a way of talking about it that’s consistent with human evolution, human prehistory, and human history.

I should say that Oswald Spengler does make an attempt to give an account of the cyclical view of history that is not mere myth. Spengler believes that man starts out primitive and rude. There are problems with Spengler’s view, but Spengler is basically very consistent with Vico. However, Spengler was not, as far as I can tell, influenced by Vico.

Indeed, one of the most interesting things about Vico is his lack of influence. Vico came up with the counter-Enlightenment 50 years before anybody else. But nobody read him. He died in 1744. His works were unread for almost a hundred years. There are only two thinkers of real first-class merit who could be described as fundamentally influenced by Vico. One is Georges Sorel, the syndicalist who has a lot to say to us, and the other is James Joyce.

As an aside, I once taught a course on Vico’s New Science, and I began by passing out the first page of Finnegans Wake and reading it aloud. My students were shaking their heads and were thinking, “He’s gone mad.” When I finished, I told them, “I’m not going to comment on this. Just tuck it into the back of the book, and at the end of this class we are going to read this page again.” So, at the end of the course, we pulled out the first page of Finnegans Wake, and we started reading through it, and as we got into the first sentence people said, “Oh! That’s Vico! I see it now!” In the first sentence, Joyce talks about “the commodious Vicus of recirculation.” Vicus means path; Vico comes from the term for path. Vico’s New Science is the single most influential text on Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, and a basic understanding of Vico turns Finnegans Wake from schizophrenic leprechaun gibberish to one of the great epic poems of the 20th century. It’s a poem about everything, because Vico was really writing about everything, because he’s writing about the whole of human history, but the whole of human history touches on everything else. So, I’ll commend this to you as an aid for reading Joyce should you ever be tempted to do that as well.

Like Hesiod and the Hindus, Vico talked about four ages: there’s an Age of Gods, an Age of Heroes, and an Age of Men, and the fourth age doesn’t have a name, but it’s an age of dissolution where things fall apart. The Hindus call the first age the Age of Truth, the Satya Yuga, and then they have the two other yugas, which are just named the third and second age, basically the Treta Yuga and Dvapara Yuga, and then the last age is the Kali Yuga, the dark age, which is the age of disintegration. With Hesiod, you have the Age of Gold, the Age of Silver, the Age of Bronze, and the Age of Iron. In Finnegans Wake, Joyce names the four ages Eggburst, Eggblend, Eggburial, and Hatch-As-Hatch-Can. Eggburst, Eggblend, and Eggburial also refer to Vico’s three primal institutions: religion, family, and burial of the dead.

Vico didn’t just talk about myth, he used myth. This is Vico’s myth about how the primal institutions arose.

He began by bidding us to imagine the world after the flood, because he had to square everything with the Bible. The sons of Ham and Japeth have wandered off to found the Gentile nations, and they have grown rude and crude and unlettered. They’ve lost language. They’ve lost culture. They’ve become solitary, asocial. They’ve become cyclopean. He actually believed they grew to giant size. So, giants wandered the forests of the Earth after the flood, and these giants would fornicate occasionally if they would bump into a giantess, but they didn’t form any families. They didn’t have language; they didn’t have conventions of any sort; but they had a powerful imagination.

Now imagine what happened after the flood. As the Earth dried out, the atmosphere would start getting humid. Thus there must have been terrible storms all over the world. When the thunder rumbled and the lightning flashed, the giants were terrified. (This is Joyce’s “Eggburst.”) Their powerful imaginations personified the cause of their fears, and they cried out the word “Jove!” They gave a name to the thunder. This is Vico’s account of the origin of the first primal institution, religion.

For Vico, mankind formed language and gods at the same time. Ernst Cassirer, a 20th-century German-Jewish philosopher of culture, has a book on Language and Myth which makes essentially the same point in non-mythical terms. Language and myth have the same beginnings. They start with names. Primitive men name things in order to master things that frighten them. The primal motive behind the creation of religion is coping with things that cause us fear. This is an Epicurean account of the origin of religion. And since we don’t want to be ruled by fear, the Epicureans argued we have to get rid of religion. This is part of the implicitly revolutionary aspect of this form of materialism. If religion is caused by fear, then as we grow up as human beings and become modern, we don’t want to be ruled by fear anymore. So goodbye to all that.

Vico continued his tale. The giants conceived that the sky was a god. Since the sky is always above us, they imagined that the sky was always watching them, and that made them self-conscious. So, instead of just fornicating with random giantesses they would encounter in the woods, they would drag them off to caves and lairs where they could do their business under cover. This was the beginning of the second primal institution, the family, what Joyce called “Eggblend.” The family arrived because the giants felt shame before the gods they imagined into existence.

Since the caves were in one place, the giants ceased to wander. When they fell dead, they did not leave their bodies behind. They had to dispose of them, before they started to stink. Vico believed that the burial of the dead was one of the ways that man invested something in the landscape around him, becoming a settled rather than a nomadic being. Originally, our relationship to land was a sacred one, a relationship of mutual belonging. Property that you just buy and sell was a much later invention.

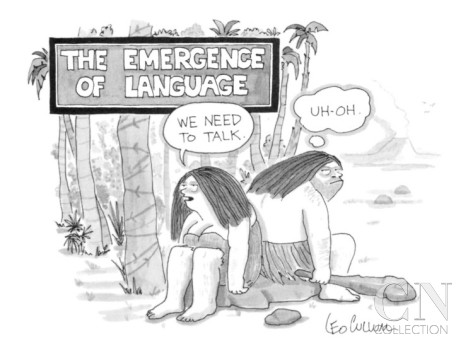

Vico’s account of the origins of the primal social institutions is an attempt to imagine how primitive minds can begin the process of evolving complex institutions that are not consciously designed. Vico’s view is radically at variance with one of the most common Enlightenment ideas, namely social contract theory. Culture is a realm of shared conventions. How do you create conventions? Well, you sit down and you agree on things. You agree to drive on the correct side of the road, for instance. There’s a New Yorker cartoon on the origin of language, and it illustrates the absurdity of the Enlightenment’s idea of how conventions come about. A cave man and a cave woman are seated on the ground, back to back. The cave woman says, “We need to talk.” The cave man says, “Uh-oh.” That’s how language came about! We needed to talk, so we talked! The joke, of course, is that language could not have arisen that way, because she was already using it. She already had language to say “We need to talk.”

In the same way, conventions cannot be created by a social contract, because such a contract presupposes that society, language, civility, mutual trust, and contracts already exist. Therefore, the idea that governments are instituted by contract to secure natural rights—as we see in the US Declaration of Independence—is preposterous. Governments never were instituted like that. But of course revolutions can be.

On Vico’s account, governments grew from patriarchal family relationships and extended tribes. This process, moreover, took place by the trial and error of primitive and irrational beings, not conscious reasoning and design. These were very crude people. Language developed slowly over time. The ability to reflect critically came about very late. Even today, it hardly exists at all in some people. Most people are passive followers, even really smart people. So, the idea that critical reason is at the root of society is preposterous.

The Enlightenment attitude that institutions should be founded on reason leads to the conclusion that existing institutions that can’t give a rational account of their utility should be done away with. For Vico, this is basically a kind of nihilism that will dissolve society. So, for Vico, the fourth age is one in which the early “barbarism of sense,” as he calls it, is replaced by a new barbarism, the “barbarism of reflection.” The barbarism of reflection strives to make the world a better place. But it ultimately dissolves the bonds of sociality, and therefore society returns to chaos.

To sum up, the Age of Gods is the first age when religion, family and settled life begin. The Age of Heroes is the second age where you have the rise of aristocratic societies. It’s the Homeric Age. The Age of Men is the age of popular government, democracy, and in the fourth age, Hatch-As-Hatch-Can, the Kali Yuga, the dissolution comes about when, within these democratic societies, skepticism and materialism and the barbarism of reflection take over and dissolve the constituent bonds of society.

Now with this in mind, I want to read a couple of passages from the end of The New Science. And as you will see, I think we should read Vico not only for the light that he shines on society, but also for the beauty of his words, for he was a professor of eloquence. Perhaps the biggest impediment to reading Vico is that his illustrations presuppose too much familiarity with Roman history. If he were alive today, he’d no doubt be citing examples from Star Trek.

As the popular states, democracies, became corrupt so also did philosophies. They descended to skepticism. Learned fools fell to calumniating the truth. Thence alone arose a false eloquence ready to uphold either of the opposed sides of a case indifferently. Thus it came about that by abuse of eloquence like that of the tribunes of the plebs of Rome and the citizens who were no longer content with making wealth the basis of rank . . . [Here he goes off into Roman history. I’m going to skip forward.] Thus, they caused the commonwealths to fall from the perfect liberty into the perfect tyranny of anarchy or the unchecked liberty of the free peoples.[1] [3]

Vico is talking about how demagogues whip up democracies and install themselves as tyrants. So, the fourth age really is the Age of the Tyrant. Then he says:

To this great disease of cities, Providence applies one of three great remedies in the following order of human civil institutions: First, it ordains that there be found among these peoples a man like Augustus to arise and establish himself as a monarch and by force of arms take in hand all the institutions and all the laws which, though sprung from liberty, no longer avail to regulate and hold it within bounds. On the other hand, Providence ordains that the very form of the monarchic state shall confine the will of the monarchs in spite of their unlimited sovereignty within the natural order of keeping the peoples content and satisfied with both their religion and their natural liberty.

This is what Spengler calls Caesarism, and that’s the best outcome. The next best outcome is this:

Then if Providence does not find such a remedy within, it seeks it outside and since people so far corrupted have already become naturally slaves of their unrestrained passions of luxury, effeminacy, avarice, envy, pride and vanity and in pursuit of the pleasures of their dissolute life are falling back into all of the vices characteristic of the most abject slaves, having become liars, tricksters, thieves, cowards and pretenders, Providence decrees that they become slaves by the natural law of the gentes which spring from the nature of nations and that they become subject to better nations, which, having conquered them by arms, preserve them as subject provinces. Herein the two great lights of natural order shine forth.

This is very interesting: first, that he who cannot govern himself must let himself be governed by another who can, and second, the world is always governed by those who are naturally fittest. This is a long time before Darwin, much less Social Darwinism, came along, but this is in Vico.

If a corrupt society is unlucky enough to find a Caesar from within or from without, then society goes to perdition. This is Vico’s description of perdition:

But if the peoples are rotting in that ultimate civil disease and cannot agree on a monarch from within and are not conquered and preserved by better nations from without then Providence for their extreme ill has its extreme remedy at hand. For such peoples like so many beasts have fallen into the custom of each man thinking only of his own private interests, but have reached the extreme of delicacy, or better of pride in which like wild animals they bristle and lash out at the slightest displeasure.

Sounds like the internet to me.

Thus, no matter how great the throng and press of their bodies they live like wild beasts in a deep solitude of spirit and will, scarcely any two being able to agree since each follows his own pleasure or caprice.

Sounds like the New York subway, where there’s this great press of people who are sunk in the solitude of individualism. There’s nothing that holds them together except the press of their bodies and the tube that they’re going through.

By reason of all this, Providence decrees that through obstinate factions and desperate civil wars they shall turn their cities into forests and the forests into dens and lairs of men. In this way, through long centuries of barbarism rust will consume the misbegotten subtleties of malicious wits that have turned them into beasts made more inhuman by the barbarism of reflection than the first men had been made by the barbarism of sense. For the latter displayed a generous savagery against which one could defend oneself or take flight or be on one’s guard, but the former with a base savagery and soft words and embraces plots against the life and fortunes of friends and intimates. Hence, people who have reached this point of premeditated malice when they receive this last remedy of Providence are thereby stunned and brutalized, are sensible no longer of comforts, delicacies, pleasures, and pomp but only of the sheer necessities of life.

Vico believed that there’s a single human nature. He calls this our common mental dictionary. He’s a universalist in that sense. He’s not a cultural relativist. What underlies culture is a universal human nature that, under the impress of natural necessity, will give rise to culture again and again. So if we return to the barbarism of sense, we won’t tarry there long, because the self-actualization of man requires that history begin over again.

This is an account of a cyclical view of history grounded in an understanding of human nature. Primitive men are crude but vital and imaginative. Imagination, spurred by vitality and natural necessities, gives rise to institutions. As mankind becomes more reflective and intellectual, however, we become alienated from vitality and from historically evolved institutions. Reflection dissolves our participation in society, our identity with society. We become selfish, individualistic, and deracinated. But such people cannot maintain a civilization. So civilization collapses from the barbarism of reflection. Men return to the barbarism of sense, and the process begins all over.

Thus Vico takes an account of human nature that’s consistent with natural science and combines it with an account of history and culture that leads to conclusions that people on the New Right support.

That’s my brief for Vico. Giorgio Almirante, the founder of the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement, once said that Julius Evola was “our Marcuse, only better.” So I give you Giambattista Vico: our Marx, only better.

Note

[1] [4] The New Science of Giambattista Vico, Revised Translation of the Third Edition (1744), trans. Thomas Goddard Bergin and Max Harold Fisch (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1968), Conclusion, pp. 417–26.