An Alt-Right Constitution?

Posted By F. Roger Devlin On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledJohn E. Finn

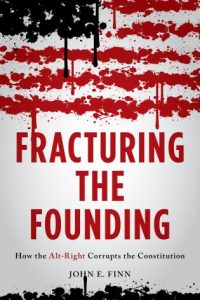

Fracturing the Founding: How the Alt-Right Corrupts the Constitution

Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019

The first thing to understand about this polemical work is that it has very little to do with the Alt Right. As readers of this site are aware, the core of the authentic Alt Right is white racial advocacy unencumbered by taboos against the discussion of human differences or Jewish influence; this core is surrounded by a looser periphery of youngish Internet trolls who enjoy making life miserable for liberals and Cultural Marxists. The movement is not greatly concerned with constitutional law.

John E. Finn is a retired liberal professor of constitutional law whose ideas about the Alt Right are derived largely from an uncritical reading of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s publications, The New York Times, and other hostile sources. This results in howlers like calling the Proud Boys a “paramilitary organization.” The Times once published a silly article entitled “The Alt-Right’s Asian Fetish”; Finn obediently lists the alleged “fetish” as a defining trait of the movement. He appears largely unfamiliar with the actual writings of the Alt Right.

The general tenor of Finn’s book is captured by his reference to all who think the First and Second amendments mean what they say as “speech freaks” and “gun nuts.” He mocks the “paranoia” of gun owners who imagine that any firearms regulation is a prelude to confiscation, but then turns around and acknowledges that he himself would prefer to see the Second Amendment repealed. And only ignorance can explain his assumption that the Dissident Right’s struggle against censorship and deplatforming relies exclusively on appeals to the First Amendment. He does not even mention Jared Taylor’s promising lawsuit against Twitter, which involves far more sophisticated arguments.

But Finn’s principle target is not the Alt Right at all; it is “Constitutional Patriotism.” This amorphous, largely evangelical Christian movement promotes an understanding of the US Constitution that stresses the founders’ original intent, along with a broad, literal reading of the First, Second, and Tenth Amendments; it also rejects the Fourteenth and certain other post-Civil War amendments. Finn confounds Constitutional Patriots with the Alt Right, either because he thought it would help sell books or because he is the sort of liberal for whom all non-Leftists are indistinguishable “Right-wing wackos.” The confusion is useful to his argument, however, because it lets him attribute Alt Right racialism (“white supremacism”) to Constitutional Patriots who say little about race.

It should be pointed out that the Constitutional Patriots’ general approach to interpreting America’s founding documents has a perfectly respectable pedigree which can be traced through the Southern conservative tradition back to the Anti-Federalists of the founding era itself. In more recent times, this way of reading the US Constitution was extensively developed by M. E. Bradford.

Finn would certainly be unsympathetic even to the most sophisticated presentation of originalism. Whereas Bradford found the Constitution “notably short on abstract principles and modest in any goal beyond limiting the powers of the government it authorizes,” Finn believes it envisioned a “secular, democratic, inclusive and egalitarian community.” Whereas Bradford immersed himself in the documents of the founding era to understand the Constitution as the founders themselves did – even writing a book entitled Original Intentions (1992) – Finn considers the federal judiciary’s understanding of the Constitution authoritative, presumably including the Supreme Court’s discovery of rights to abortion and gay marriage in the penumbras and emanations of various clauses and amendments. He suggests that such alleged discoveries “continue the work of the founders,” whom originalists are content merely to venerate. (The accusation in his title, that originalists are “fracturing the founding,” is thus somewhat disingenuous.)

But Finn never mentions Bradford or any serious scholar who has developed the originalist reading he opposes. He makes things easier on himself by focusing exclusively on the popular movement of self-described “Constitutional Patriots,” a self-taught group which believes an adequate understanding of the US Constitution is within the grasp of anyone of normal intelligence willing to devote a little time to reading and studying the document itself. This movement is quintessentially Protestant, mimicking the reformers’ teaching that believers should study the scriptures directly, without the aid of external authorities. Just as the reformers believed every man could become his own theologian, the Constitutional Patriots think every man can become his own constitutional lawyer. Some figures in the movement market recorded lectures and study guides to facilitate private study. Unsurprisingly, some amateur constitutionalists have developed highly idiosyncratic and occasionally ridiculous theories.

Constitutional Patriots emphasize that the US Constitution does not grant rights such as freedom of speech, which the founders understood as natural or God-given, but merely reserve such rights to the people by forbidding the federal government from interfering with them. On this point, they are perfectly correct. But some in the movement go on to argue for such “reserved rights” as driving on public roads without a driver’s license. From there, things quickly get crazier. Finn cites a Website calling itself The Embassy of Heaven, which sells its own license plates and vehicle registrations for a one-time fee of forty dollars. The so-called Embassy advises drivers pulled over by police officers to:

. . . state that you are a citizen of Heaven traveling upon the highways in the Kingdom of Heaven for the purpose of evangelizing. . . . If they try to claim you are on the highways in the State, remind them that highways are multijurisdictional. If you were using the highways in the State, you would need their permission in the form of a State license. But since you are using the highways in the Kingdom of Heaven, you cannot be trespassing upon the State. They normally will try to have you acknowledge that you are in their State. Remember, there is no communion between light and darkness. Stay in the Kingdom of Heaven, regardless of the pressure.

Somewhat more practically, the Embassy of Heaven recommends that those following their advice drive a cheap car to minimize financial loss when police confiscate it.

Finn makes the valid point that for all their distrust of government, including judges, lawyers, and police, amateur constitutional theorists evince a touching faith in law as such: They believe there exists a “true” way of understanding constitutional law which, rightly acted on, can deliver them from their enemies, the agents of America’s present unconstitutional regime (whose inception is variously dated to 1865, 1917, or 1933). One strand of Constitutional Patriotism argues that the Sixteenth Amendment, which provided for the income tax, either was not properly ratified or is invalid due to its incompatibility with the founders’ Constitution. Finn calls their crusade “a scam run by grifters who dress their con up in appeals to the Constitution and the ‘American’ tradition of resistance to unfair taxation which they foist upon their marks.” Some of the credulous have wound up in jail.

Finn also reports on the Common Law Court movement, whose adherents believe anyone can set up a legally valid court or grand jury with the authority to summon jurors, place liens on property, or even convict government actors of treason, complete with sentence of death by public hanging. Closely related is the Sovereign Citizen movement, who hold that Americans subject themselves to government authority only when they interact with the government. They argue that Americans can “redeem” their natural personal sovereignty by withdrawing from all involvement with the government. Sovereign Citizens refuse all government benefits, refrain from voting, and do not use credit cards or own insurance policies, securities, bonds, or interest-bearing bank accounts. Some will not even write ZIP codes on their mail. They believe a “redeemed” Sovereign Citizen is no longer subject to American law. Sovereign Citizens have been involved in shootouts with law enforcement.

Much of this reportage on the loopier reaches of Constitutional Patriotism, which occurs mainly in the book’s last two chapters, is interesting and unobjectionable – enough to warrant the measured praise of George Hawley’s blurb: “Finn has provided a helpful service by explaining how leading figures of the far right approach the Constitution and by informing readers why legal scholars reject their interpretation.” But as the author of two books on the Alt Right, Hawley should also know that Constitutional Patriotism is a different animal.