Not Over: Al Qaeda’s Story

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledAli Soufan

Anatomy of Terror: From the Death of Bin Laden to the Rise of the Islamic State

New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2017

Ali Soufan is famous, to put it mildly. A fictionalized version of him was played by Tahar Rahim in Hulu’s miniseries, The Looming Tower [2]. He is also a bestselling author. The foundation of Soufan’s fame is the fact that he was an FBI[1] [3] agent investigating Al Qaeda prior to, during, and after 9/11. Today, Soufan has a successful security consulting business. Ali Soufan’s success as an FBI agent during the war against Al Qaeda is due to Soufan’s background – and the fact that he is pretty smart. He is a Lebanese-born Muslim immigrant who came to Pennsylvania as a child, and who is fluent in Arabic.

From a mainstream perspective, Soufan is an example of the “blessings of diversity.” However, his was really a lucky break. Soufan is operating in a sociocultural ecosystem that deserves further analysis. A study of this ecosystem will also produce some contradictory, but important, ideas.

- There has been a hunger in post-1965 America for efficient, heroic, patriotic “G-Men” (FBI agents, CIA, soldiers, police, etc.) of Third World, immigrant background. Finding these heroes masks the obvious problems that have arisen since “civil rights.” A single Colin Powell can paper over the fact that there is a long-running trend of smoldering problems with blacks in the military’s line units. A “Colin Powell” can cover up twenty-five years of “polar bear hunting” patrols and race riots at the PX on military bases – as well as disasters such as black-run Detroit. Likewise, one Ali Soufan covers for a great many Major Hassans. There is simply no corresponding level of white crime or terrorism; to claim such is to deliberately misread the data.

- Who lost Syria? [4] This region was not always anti-American, and filled with violence and strife. Despite the Islamic veneer, Lebanon and Syria are not a cultural world apart from Europe in the way Saudi Arabia is. The region was once very much part of the eastern Greek world. Syria was host to the Decapolis (Δεκάπολις) and was highly civilized. Syria hosts many different religious confessions, including a large Christian community. Beirut was also quite civilized and was once called the Paris of the East. With that in mind, there is probably a deep ethnic, racial, and cultural reason why a Lebanese man such as Soufan turned out to be true to his adopted homeland while people from Yemen, Saudi Arabia, or other places end up being dangerous. It could very well be that Syrians, Lebanese, and Americans have much in common and much to offer each other. There should be a national-level soul-searching exercise regarding the current state of Syria and Lebanon, as well as America’s relationship with them. Indeed, America’s relationship with the people of that region was very positive from the nineteenth century until the 1950s [5].

Ali Soufan is a serious man and a serious thinker. When I started to read his book, I had a suspicion that he was a Counter-Currents reader – he’s not, as far as I can tell, but he does hit upon themes often published on this site. Like Greg Johnson, he argues that Francis Fukuyama’s “end [7] of history [8]” concept was unstable. All that was needed to bring down that system was one man with Thumos (θυμός) and an idea. And Soufan’s Introduction to the book is titled “Friends and Enemies” – a philosophical concept explored by the Rightist philosopher Carl Schmitt [9].

The New Rising of the Islamic World

Soufan’s approach is to describe the world of ideas through men of action, i.e. the top-level terrorists themselves. Before proceeding further, one must first discuss the ideas. These ideas are commonly packaged in a single, very poor term: “Islamism.” Unfortunately, this term is unwieldy and is unable to truly describe this vast socio-religious upwelling in the Islamic world. This movement had picked up steam by the First World War. At the time, Lothrop Stoddard wrote:

The Great War thus found Islam everywhere deeply stirred against European aggression, keenly conscious of its own solidarity, and frankly reaching out for Asiatic allies in the projected struggle against European domination. Under these circumstances it may at first sight appear strange that no general Islamic explosion occurred when Turkey entered the lists at the close of 1914 and the Sultan Caliph issued a formal summons to the Holy War. Of course this summons was not the flat failure which Allied reports led the West to believe at the time. As a matter of fact, there was trouble in practically every Mohammedan land under Allied control. To name only a few of many instances: Egypt broke into a tumult smothered only by overwhelming British reinforcements, Tripoli burst into a flame of insurrection that drove the Italians headlong to the coast, Persia was prevented from joining Turkey only by prompt Russo-British intervention, while the Indian North-West Frontier was the scene of fighting that required the presence of a quarter of a million Anglo-Indian troops. The British Government has officially admitted that during 1915 the Allies’ Asiatic and African possessions stood within a hand’s breadth of a cataclysmic insurrection.[2] [10]

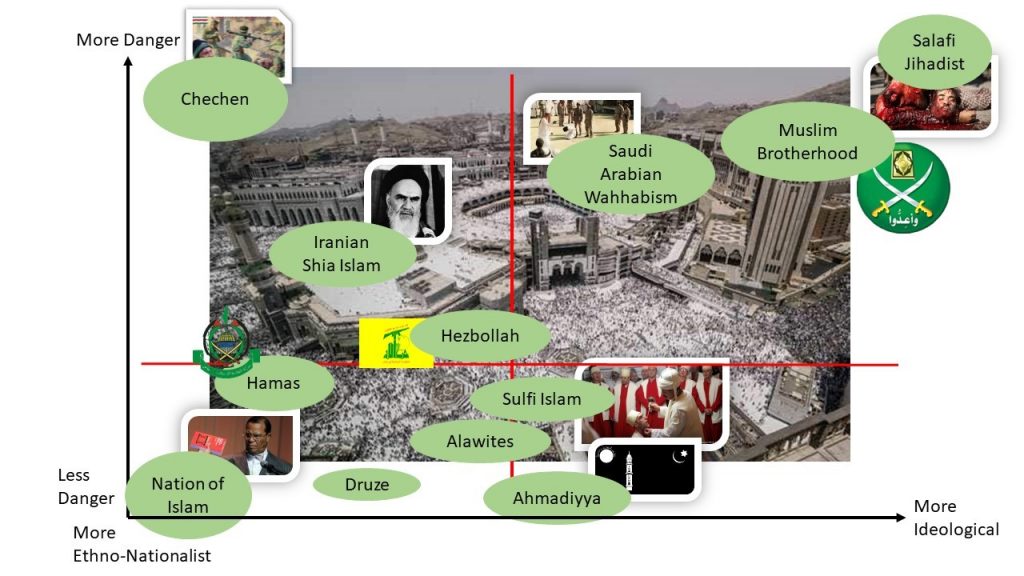

When the British left Egypt, this stirring continued. Islamism itself (see the chart below for some further thoughts) was weaponized ideologically by Sayyid Qutb. Born in 1906 and raised in Egypt, Qutb lived in the United States as a student for a period during the late 1940s. He came away from America with a deep hatred for its culture (including its haircuts) and a new appreciation for his Islamic heritage. Upon his return, Qutb became the intellectual leader of the Muslim Brotherhood. He was hanged for his writings by Egypt’s Nasser government in 1966.

[11]

[11]There is simply too much malarkey regarding Islam in America’s mainstream information environment. Islam itself is a broad religious movement that covers many different types of people living in vastly different circumstances. The graph above assumes that Samuel Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations is both true and ongoing. It measures how dangerous an Islamic group is to whites by how ideological it is. On the vertical (Y) axis, Islam becomes a greater danger the further up the chart the group is. On the horizontal (X) axis, a group becomes more ideological rather than ethnonationalist the further to the right one goes. The graph doesn’t include all Islamic groups, of course.[3] [12]

Pretentious American liberals – those who think they can think, and are thus truly dangerous – can find much to mock in Qutb’s anti-American writings. “Hating America for its haircuts,” wrote one such critic [13], “cannot be distinguished from hating for no sane reason at all.”

However, Qutb and his religious ideas should be taken very seriously. The Egypt of Qutb’s time was a nation emerging from centuries of occupation by foreign powers. When Egypt became independent, its people had to assert an identity, and fervent Islamic belief was one such possible identity. Egypt, from the Battle of el-Alamein to the Camp David Accords, was buffeted by wars, new ideas, and rapidly-changing political circumstances. In such a situation, one should not be surprised that a serious thinker would come along to fulfill a need in that time and place. It is also not surprising that such a man would be religious, for there is likely a Darwinian advantage to religious belief.

After Qutb’s execution, he became a martyr, and his ideas influenced those who assassinated Egypt’s President, Anwar Sadat, at a military parade in 1981. After Sadat’s slaying, many in the Muslim Brotherhood were jailed. Those who were imprisoned eventually emerged with new contacts and skills. Many of them volunteered to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan (ironically, with CIA backing) – which is likewise where Al Qaeda got its start.

Egypt’s jails became a university for jihadis, of sorts. Qutb’s ideas had gone viral, and other Islamic thinkers carried on his work. During the war against the Soviets in Afghanistan, many of the mujahideen were or became acquainted with Qutb’s work. Ultimately, Qutb’s ideas formed the intellectual foundation for Salafi jihadism: the ideology of ISIS, Al Qaeda, and nearly every other Islamic group that makes use of terrorism to achieve its goals today. Soufan argues that the Egyptians make the most able terrorists because many of these jihadists first gained experience in the large and efficient Egyptian military. Egypt also has many cultural centers, as well as extensive connections with the wider world. It has never been hard to travel to and from Egypt.

The Men of Action Influenced by Sayyid Qutb

Soufan starts his study of the men of action who have followed Salafi jihadism with Osama bin Laden’s final days. From his walled compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, the old terrorist watched the news by satellite TV, but didn’t send e-mails or make phone calls, fearing that he could be located if he did so. Osama communicated with his followers exclusively through couriers. Soufan doesn’t go into detail on how bin Laden’s whereabouts were discovered as much as his day-to-day activities and family life after 9/11. Osama still directed Al Qaeda, and he was excited when the Arab Spring broke out, but his worldview and focus emphasized that jihadis should continue to focus on the “Far Enemy” – the United States – rather than the “Near Enemy” – the Shi’ites, nationalist Arab governments, Israel, or the jihadis’ other local foes. This was Al Qaeda’s great innovation, as opposed to all the Islamist groups that had come before it, which believed in settling accounts regionally before taking on the West directly.

Soufan contrasts bin Laden with Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. Zarqawi had his own terrorist organization in Jordan which he took to Iraq shortly before the US invasion in 2003, but merged his group with Al Qaeda in 2004, becoming “Al Qaeda in Iraq.” Zarqawi was something of a loose cannon in that organization. He didn’t just work with Islamists, but networked with a great many Ba’athists and Iraqi Army personnel who had been rendered unemployed by the American occupation authorities shortly after the invasion. Unlike bin Laden, Zarqawi chose to focus on the “Near Enemy” in Iraq, the Shi’a in particular. It was Zarqawi who amplified the sectarian violence in Iraq and who first popularized beheading videos there. These spectacles eventually grew into the macabre ISIS snuff films. After his assassination by the Americans in 2006, his surviving followers eventually created ISIS – and they turned out to be far more capable than Zarqawi had been. And just like the Muslim Brotherhood in the 1980s, Zarqawi’s followers had an impromptu jailhouse university of jihad – at Camp Bucca, an American prison where insurgents were held.

Another major terrorist profiled is Anwar al-Awlaki. This man was a Fourteenth Amendment American of Yemeni heritage. Al-Awlaki personifies global jihad. He grew up in America, was not poor, was highly educated – but still didn’t fit in, so he went about preaching jihad in a way that other Muslims living as a minority in foreign lands could understand. Al-Awlaki’s story has been repeated many times – every time the alienated children of Muslim immigrants in the West take to jihad. Al-Awlaki and those like him are the reason why birthright citizenship should be eliminated.

Ayman al-Zawahiri is the last of the major terrorists profiled in this book. He has been Al Qaeda’s leader since bin Laden’s death. Like many radical activists, Zawahiri is an educated, upper-class man from a good family. Before becoming a full-time jihadi, he was a surgeon in the Egyptian Army. He still writes and issues communiqués. However, Zawahiri doesn’t command the same respect and authority that bin Laden had, given that he has committed several gaffes and mistakes that have diminished his reputation in the global jihadi community.

While he doesn’t have bin Laden’s glamour and sang-froid, Zawahiri is an effective and efficient leader, and this is what that kept Al Qaeda going while Osama bin Laden was the most hunted man in the world. Written works that were published by Al Qaeda after 9/11 with Zawahiri’s able support deserve some mention. The first is The Management of Savagery: The Most Critical Stage Through Which the Islamic Nation Will Pass [14] by Abu Bakr Naji. Its central concept is something of a “worse is better” idea. Like the Bolsheviks before them, the jihadis believe that they can make gains in areas where law and order have broken down, and thus they seek to engineer and then exploit such situations. This work has been a major influence on the Islamists in Syria. The second is The Call of the Global Islamic Resistance [15] by Abu Musab al-Suri, which is an outline of a long-term strategy for defeating the West through non-centralized, leaderless resistance – which is the strategy the jihadis have been pursuing in the West since 9/11.

What makes this new form of Al Qaeda so dangerous is that it is something of a downloadable franchise that is easily accessible by people of Islamic background anywhere in the world – and in the West in particular – who don’t necessarily have any connection with one another, and thus can’t be easily detected or tracked. It has also caused Western governments to be quite wasteful: all that any group in the Muslim world which wants access to stacks of cash and weapons needs to do is announce that they are fighting “Salafi jihadists” or “Islamist terrorists,” and presto, it will quickly arrive on their doorstep.

Alas! Syria is Lost

Soufan gives a good overview of the Arab Spring and compares it to a similar event in the 1950s. He also talks about the structural problems in the Syrian government of Bashar al-Assad, as well as the other causes of that nation’s ongoing civil war. It’s a sort of Cliff’s Notes version of the road to war there. He does mention some of the outside forces that contributed to the bloodbath as well, particularly the impact of the American invasion of neighboring Iraq. Another factor was Syria’s ceasing to be (at least nominally and unenthusiastically) an American ally, as it was during the Persian Gulf War of 1991.

But Soufan doesn’t exclusively blame America. He is just as critical of both Turkey and Saudi Arabia’s involvement in Syria. He makes much of the Gulf Arabs and their sponsorship of ISIS. In Syria, the Turks and Saudi Arabians in particular have put themselves in a bind. Like the Americans in Vietnam, today the Turks and Saudis are stuck in a war that they can’t win, dependent as they are on morally compromised and ineffective local allies. Simultaneously, they believe they will have suffered a major strategic defeat if they withdraw.

The decadent House of Saud seems to operate on an intellectual wattage similar to that of George W. Bush as well. This backwards kingdom of sand has long turned a blind eye to its returning jihadi terrorists, and many of its wealthiest and most prominent citizens have quietly backed Islamist terrorism abroad for decades. Regardless, these same terrorists are as quick to attack Saudi facilities as those of any other. Indeed, in 2016, Salafi jihadis bombed the mosque housing the Prophet Muhammad’s tomb in Medina [16].

That Which is Not Said . . . But Still Exists

There are a few other ideas I wish to explore that Soufan doesn’t go into. The first is Israel, and American support for Israel. The fact that a large group of Arab Muslims and Christians have been displaced by Israel remains one of the world’s great injustices. This lingering issue has several edges: Palestinians have little recourse apart from violence to pursue their objectives; their violence becomes a testing ground for new terrorist methods; and further, their treatment by Israel radicalizes others. Meanwhile, the Israel lobby in the US causes America to pursue goals that are not in its own interests. Hence, Assad’s Syria becomes an enemy simply because Israel wants it, not because it serves the American people.

Second, there seems to be a symbiosis between Islamist uprisings, especially those in the West, and black race riots. These riots and disorders spread when there is a President who is sympathetic – or appears to be sympathetic – to blacks (as with Lyndon Johnson), or to both blacks and Muslims (Barack Obama). In Obama’s last term, blacks rioted, and there was a spectacular series of jihadi terrorist events. These disorders stop when an unsympathetic President is elected. Additionally, it is well known that the United States prior to President Trump’s election was sponsoring “moderate Syrian rebels” and the “Free Syrian Army.” These dubious groups were sympathetic to the various jihadi movements, and it is not much of a stretch to presume that American money was winding its way to Muslim ghettos in Europe and elsewhere to fund the activities of dangerous men.[4] [17]

Third, ethnonationalism is a far better way to arrange society than an endless attempt to create a perfect society based on religious ideals. A society based on ideals rather than flesh and blood is one of endless domestic strife, since the vision of how those ideals should be realized will continue to change forever. In other words, in a propositional nation, if one doesn’t keep up with the ideals of the mainstream, one stops being a citizen. A Salafist society, as envisioned by the jihadis, is a propositional nation, and it will always end up being preoccupied with fighting a never-ending stream of “Near Enemies” as new ideas arise and old ideas are pushed aside.

Soufan argues that Islam-inspired terrorism will be with us for a long time. However, one wonders what will happen should the movement burn itself out, as other jihadist movements have in the Islamic world’s history. In particular, it appears that the war against ISIS is coming to a close. This white advocate can’t help but think about how to manage a limited victory such as this one. The critical thing is to keep out the refugees. All violent Third World social movements – from the Rwandan genocide, to jihadism, to the Khmer Rouge – seem to have a built-in Plan B. When the idea goes wrong, all the ex-terrorists, thieves, and murderers make like a race car to the bread lines in any white, Western country they can reach. Indeed, it seems that, in the end, these people are every bit as satisfied in asking for handouts and hassling whites on streetcorners as they were when they made beheading videos – no matter how serious the ideology they once adhered to was.

Notes

[1] [18] It is time to consider abolishing the Federal Bureau of Investigation entirely. First, the institution has no focus. In 1965, when America intellectually lost its white, Western identity, the FBI ceased to defend a particular community. Now, the FBI has shifted to only defending itself. The FBI has become something of a Praetorian guard, and recently it was exposed to have attempted a coup against a constitutionally-elected President. This focus on only defending itself is the reason why the organization has become listless. While the FBI looked for non-existent Russian control of a figure who’d been in the public eye for decades, it failed to discover the underlying motives of the perpetrator of the 2017 Las Vegas mass shooting. (ISIS claimed responsibility.) If the press hadn’t memory-holed that shooting, the public would have been far angrier. How the FBI handled the Americans at Waco was murderous, while the Islamic terrorists who carried out the first World Trade Center bombing in 1993 got gentlemanly treatment. Additionally, the FBI sponsors “informants” who are often extremely dangerous men. For example, the limo driver who killed an entire wedding party in 2018 due to his Third World-level of incompetence and stupidity was a Muslim FBI informant. The FBI is something of a self-licking ice cream cone. It is really more trouble than it is worth. The only thing it has successfully managed is the elimination of kidnapping for ransom. But all of its law enforcement duties could be carried out by state agencies.

[2] [19] Lothrop Stoddard, The New World of Islam (Bungay, Suffolk: Richard Clay & Sons, 1922), p. 48.

[3] [20] I wish to repackage C. S. Lewis’ idea, expressed in his book The Last Battle [21] (1956), regarding whether or not Islam is good in a general sense or not. That which is good is good irrespective of the deity in whose name the good is carried out, and that which is evil is evil regardless of whatever deity is invoked in such a circumstance. It is true, however, that all Islamic societies lag behind in culture, technology, industry, and economics. Also, a comment on Hamas and Hezbollah: these groups are only a danger to whites if the whites are in the territory of either group and they are pursuing Israel’s interests. Otherwise, they should be seen as ordinary political organizations with a religious affiliation, such as the Christian Democrats. Hamas is not out to get you.

[4] [22] The greatest hero in reducing ISIS and other jihadi groups was the late Senator John McCain’s brain tumor. This foolish man ensured that much American aid went to Syrian rebel groups. After the Senator passed, American policy in the region became far more rational.