A Judeo-Christian Walking the Earth:

Highway to Heaven

Posted By

Morris van de Camp

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

There needs to be formal recognition of the genre of TV shows where the protagonists “walk the Earth.” The best explanation of these was given by Jules (Samuel L. Jackson) to his partner Vincent (John Travolta) [2] in the film Pulp Fiction [3]:

Jules: First, I’m going to deliver this case to Marsellus, then, basically, I’m just going to walk the Earth.

Vincent: What’chu mean, “walk the Earth”?

Jules: You know, like Caine in Kung Fu: walk from place to place, meet people – get into adventures.

Vincent: And how long do you intend to “walk the Earth”?

Jules: Until God puts me where He wants me to be.

Vincent: And what if He don’t do that?

Jules: If it takes forever, then I’ll walk forever.

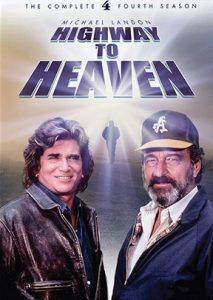

Highway to Heaven was a “walk the Earth” TV show where an angel named Jonathan Smith (Michael Landon) and his human sidekick Mark Gordon (Victor French) travel from place to place in a 1977 Ford sedan [4], meeting people and getting into adventures. The show was produced by Michael Landon himself, who also did much of the writing, directing, and editing. Highway to Heaven was Landon’s show. There are a great many tear-jerker episodes involving terminally sick kids, old people getting a second chance at love, people working through grief, and those seeking a shot at redemption. I decided to take a look at this show when I couldn’t sleep early one morning and discovered it on my newfangled TV/Internet data-streaming service. For me, watching Highway to Heaven is a trip back to my pre-teenage childhood; it’s a cultural time capsule.

The Time

Highway to Heaven takes place in the cultural context of the 1980s. Then, American culture was still deeply wounded following the disaster of the Vietnam War. There are several episodes in Highway to Heaven related to the lingering fallout from that conflict. The “overcoming” of the Vietnam War in the turkey shoot that was the Persian Gulf War [5] and pronounced as such by George H. W. Bush [6] was still unimaginable in August 1989, when the last episode was broadcast. Indeed, there was no hint that the Cold War was about to end, in the spectacular way that it did that very autumn. Additionally, the show was designed for a TV distribution system that consisted of only three national networks, plus the government’s own PBS. One could say that Highway to Heaven was broadcast in an information-restricted environment. Cable TV did exist, but generally speaking at that time they didn’t produce their own dramatic series, as is commonplace today; they mostly played reruns of shows that had been produced for the commercial networks.

In such an environment, Highway to Heaven had to have broad appeal. While the show was for all comers, one gets the sense that its primary audience was retirees. For example, in 1984, when the series’ pilot episode was broadcast, those in their 70s would have been born before 1914, so there are references to boxer Joe Lewis rather than Mike Tyson. Furthermore, in the 1980s many older people were veterans of the Second World War. As such, many episodes involved a Second World War veteran resolving his issues, such as reconciling with his adult children. These plotlines struck a chord with the 1980s audience.

The Place

While Jonathan and Mark are on a God-ordained mission to walk the Earth, they mostly walk a small corner of it; namely, southern California. There is a sense that the show was often produced on the cheap – there is, for example, a redemption between a father and his kids set in a studio lot. Additionally, many of the characters are involved in the entertainment industry, and so the show often focused on the ethical dilemmas which arise from it, such as spending a lot of time away from family or leaving one’s family to try to get a “big break.” In other words, the writers didn’t take the time to learn about people with vastly different life experiences or backgrounds. In Highway to Heaven, there’s always southern California sunshine, well-kept suburban streets, and a good economy.

Midwestern Culture, Quaker Philosophy, & Judeo-Christianity

Southern California and the greater Los Angeles area had importance for the show for other reasons, too. This area is an extension of the American Midwest – not due to its geography, but because many of LA’s white residents came from places like Iowa [7] and Nebraska. And American Midwestern culture is heavily influenced by Quakerism.

A viewer who is perceptive to cultural factors will notice that Quakerism is not splashed across the sky over Hollywood. Rather, its understated power comes from the fact that it is the social, religious, and philosophical foundation for LA’s Midwestern culture. Quakerism’s virtue is that it provides for a society where religious toleration is the highest order of things. Individuals are encouraged to follow their inner light, whatever that might be. It’s no accident that the Pentecostal movement [8] underwent critical developments on LA’s Azusa Street, and Billy Graham’s ministry likewise exploded in popularity there during a big tent revival [9]. In a Quaker society, God is love, and one is encouraged to pursue useful activities.

Quakerism as a social and religious philosophy is something worthy, but it only works in a racial context. For it to function, the bulk of the society where it takes root needs to originate from northwest Europe, specifically England’s North Midland Quaker heartland, as well as Wales, Germany, Holland, and eastern Ireland. This is where Quaker values were formed in the first place. In other words, religion follows culture, and culture follows race. As long as the bulk of the population is of that race, there is no problem.

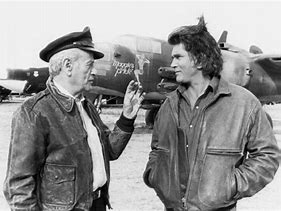

Highway to Heaven mostly keeps within the bounds of LA’s Midwestern white culture. In fact, it has to do this for the show’s charm to work. All of North America’s regional cultures are comfortable with the Midwest. The Midwestern accent is easy for everyone to understand; American news anchors typically speak with a Nebraska accent, and many call centers are in Omaha because of it. Using Midwestern culture as a form of cohesion in entertainment has another critical component: for a society to genuinely mourn, rejoice, or share emotional bonds, it cannot be diverse. The audience can weep with Jonathan as a dying child reaches out to get his last wish of “touching the Moon” – as long as that kid is white. We can really only feel the bittersweet joy of watching grandpa’s soul fly the old bomber to Heaven as he rejoins his son – who was KIA in Vietnam – if they are white (or Jews playing American whites). If the sick kid, or grandpa, or the struggling waitress, or underappreciated singer, or the bad student with the heart of gold isn’t white, the magic and the shared empathy cannot happen.

[10]

[10]Eli Wallach and Michel Landon in “To Bind the Wounds [11]” (1986). It’s an all-white episode. Diverse societies cannot genuinely mourn or rejoice.

A society’s religious foundation is important, and southern California’s Quaker foundations have much to recommend it. And at first glance, Highway to Heaven is a Christian show of the Quaker variety. However, there is a slight difference: it is theologically Judeo-Christian. Mike Landon was partially Jewish himself, and many of his closest friends, such as Lorne Greene [12], were Jewish. Hollywood is also more or less run by Jews. And Judeo-Christianity and Quakerism are very similar; from the perspective of a well-made TV series with good actors, solid stories, and wholesome values, they appear to be alike. However, there are some drawbacks that need to be discussed.

Drawbacks of Quakerism

One drawback to Quakerism is that it cannot ask – or answer – the truly hard questions. The reason why Middle America has a solid Quaker cultural framework, despite there being very few actual practicing Quakers, is that in the 1750s, the Quaker political elite in Philadelphia failed to deal with the crisis of the French and Indian War. If a young Quaker man joined the British Army and went to fight the savage Indian murdering settlers on the frontier, he was read out of the Quaker Meeting. That man thus had to switch to another Christian denomination for his religious needs.

Likewise, Quakers are prone to empty virtue-signaling. What makes it empty is that one faction of the Quakers – or any other moralistic white community, for that matter – uses its signaling to gain social advantage over others within that moral community. And there is a sharp edge to this. First Lady Dolley Madison’s father, John Payne, Jr., was a Quaker who owned slaves. When the Quaker religion determined that slavery was immoral, John Payne freed his slaves and moved to Philadelphia, starting a business. When his business failed and he filed for bankruptcy, he was excommunicated by the Quakers, regardless of his earlier idealism. The Quakers who excommunicated Payne didn’t really concern themselves with the lives or struggles of Payne’s freed slaves, or worry about those who thus came under threat from non-white violence.

Quakers need to be protected from themselves. For their society to function, they need ex-Quaker whites in the bankruptcy courts and guarding the perimeter of their community from outside threats.

Drawbacks of Judeo-Christianity

Judeo-Christianity is the philosophy of American TV, especially during the 1980s. In this philosophy, Jews are depicted as nothing more than a religious sect, not as ethnic strategists pursuing an agenda which is often hostile towards their white host society. Like Quakerism, Judeo-Christianity appears to be tolerant and supportive of finding one’s inner light – but there is a small but critical difference: it deliberately doesn’t ask certain questions, and gives some faulty answers. This especially occurs in relation to race and immigration. Highway to Heaven shows Los Angeles as a culturally Midwestern Whitopia with a gentle Mediterranean climate. However, throughout the 1980s, the city was rapidly diversifying, and racial tensions were climbing, as was clear to anyone who lived there who wasn’t in denial. In a Judeo-Christian theological framework, there is no way to address such a problem other than to scold whites or drift into nostalgia.

[13]

[13]Highway to Heaven portrayed southern California as a Whitopia during the 1980s, when racial tensions were rising. In 1992, LA’s black population put parts of the city to the torch. Highway to Heaven never seriously examined racial issues.

Consider the first season episode, “Dust Child [14]” (1984). In this episode, the half-Vietnamese daughter fathered by a white Vietnam War veteran joins her American family. As a result, it becomes a lesson on racism. Unfortunately, there are more complex issues at play in race and immigration than scolding bike-riding suburban whites who say “gook.” Highway to Heaven’s Judeo-Christian philosophy also includes the “punch a ‘Nazi’” concept. In “Dust Child,” Jonathan uses his supernatural powers to cause two whites who say “gook” to crash their bikes. He doesn’t explain to those kids why Asians moving to southern California is a good idea – probably because it is not a good policy that can be rationally explained. Also, the “half-Vietnamese orphan” situation was a well-known racket in the 1980s. Vietnamese kids who had been born after the American withdrawal but who claimed American parentage were being let into the United States, and many caused problems. The Hmong refugees who also came from Vietnam at the time turned out to be prone to crime and a welfare sink who had few redeeming qualities. But of course, this was just part of a larger immigration problem.

Another episode that tries to cover over serious issues is the first season’s “The Return of the Masked Rider [15]” (1984). In it, a group of aging actors who were movie stars in the old-time Western B-movies have to muster the courage to confront a group of black thugs in a gang called Satan’s Helpers. The story is rather silly: we get the white savior narrative, as well as the cuckservative fallacy that in crime-prone black neighborhoods there are large numbers of “good blacks” who want nothing more than to find a way to counter the power of the criminals, gangs, and drug-dealers. Nobody bothers to ask the more difficult question of why criminals, hustlers, and despots always rise to the top in black neighborhoods, cities, and nations. To do away with black crime – which in the 1980s was truly awful – one didn’t need a nostalgic return to the values of the “Masked Rider” and B-Western circuit; one needed to enact sweeping criminal justice reforms to put many blacks in prison for long sentences, as happened during the Clinton administration [16].

While Highway to Heaven discussed the impact of the Second World War and Vietnam in considerable depth, other issues of the day, such as the 1983 bombing of the US Marines barracks in Beirut, or America’s support for Israel’s invasion of Lebanon and dispossession of the Palestinians, never came up. This is because Judeo-Christianity is a moral worldview consisting of nothing but the Quakers’ empty virtue-signaling and their half-blind worldview. Its moralizing is only directed at whites – and Jewish crimes never come up.

Nonetheless, on the whole, Highway to Heaven was wholesome. To call it Jewish poison in the same league as Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan [17] would be a great injustice. Michael Landon never produced an ugly Jewish-centric show such as Lena Dunham’s Girls. Furthermore, Highway to Heaven did fill a need. In a society without diversity, there are still rules to be laid down, stubborn people [18] need to learn life’s lessons [19], and people need to express their feelings when their ailing veteran grandfather passes away. Doing this in a Judeo-Christian framework that is very close to Quakerism cannot be taken as some sort of insult or Trojan Horse, even by a white advocate from a Midwestern, ex-Quaker heritage. The show is worthwhile for the whole family, much of its dialogue is good, and many of the ideas it expresses are true.

On a personal note, rewatching the show reminded me of the cruel, unrelenting passage of time. I’ve noticed the same style of furniture seen in Highway to Heaven – stained oak hutches, tables, and oak chairs often sporting light-blue seat cushions – at estate sales. Their owners, who were of the same generation as Michael Landon and Victor French, have passed away, and their children have their own style. And the Second World War generation is almost entirely gone. I can’t help but pity those young adults who are reading this article who didn’t get a chance to talk to a veteran of that conflict; they had life stories that were unique, often starting out with the trials of the Great Depression or the Dust Bowl. Those vets who could talk about what it was like at Guadalcanal did so with as much poetry as the Iliad. In featuring so many veterans, Highway to Heaven helped to preserve that poetry.