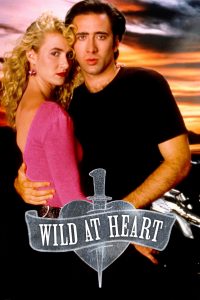

“Hotter than Georgia asphalt”

David Lynch’s Wild at Heart

Posted By

Trevor Lynch

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

Wild at Heart is not David Lynch’s best movie, but it is my favorite. I would argue, for instance, that Blue Velvet, The Elephant Man, and The Straight Story are all better films. But for some reason they do not call me back year after year like Wild at Heart.

Wild at Heart was released in the summer of 1990, when Lynch was riding high on Twin Peaks mania. It won the Palme d’Or at the 1990 Cannes film festival, albeit over vocal protests. Critics had their knives out for this film, most prominently the blockhead Roger Ebert.

I decided to give Wild at Heart a pass in the theaters because the film had been characterized to me as a boring exercise in nihilism: a tedious road picture about two sex-crazed pinheads filled with pointless weirdness, exploding heads, and running references to The Wizard of Oz. It was the Oz thing that did it. It sounded precious and postmodern, the kind of thing that college-age cineastes would self-satisfiedly snigger at in the theatre.

Seeing Twin Peaks for the first time that fall, however, whetted my appetite for more Lynch, so I watched Wild at Heart as soon as I could obtain a VHS tape. On the surface, Wild at Heart is everything its critics complained about: a freakshow of obscenity and violence and The Wizard of Oz.

But Wild at Heart is emphatically not a pointless exercise in nihilism. Indeed, there is genuine sentiment and humanity in Wild at Heart, as well as a deep moral order. It is definitely a road picture, but the road leads through the wasteland, the Kali Yuga, in which the moral order is almost entirely hidden by a fallen and degenerate world and visible only in fleeting glimpses and grotesque guises. But even in this world, what is right by nature still has the power to bring the film to a satisfying conclusion.

Wild at Heart is the story of two almost feral young Americans, Lula Pace Fortune and Sailor Ripley (played by Laura Dern and Nicholas Cage) who fall in love and go on the run from Lula’s mother, Marietta Fortune, a “crazy fucking bitch” played by Dern’s real-life mother Diane Ladd. At one point, Sailor addresses her as “Miss Fortune,” and she is indeed Our Misfortune—in pumps.

Wild at Heart is based on the neo-noir novel of the same name by Barry Gifford, who later co-authored the screenplay to Lynch’s Lost Highway. Comparing the novel of Wild at Heart to the movie deepens one’s appreciation of Lynch’s artistry. Gifford’s novel is frankly two-dimensional, and a straightforward adaptation really would have been a pointless exercise in nihilism.

Lynch seems to have responded primarily to Gifford’s colorful character names and turns of phrase. There really is something wonderfully vivid about how Southerners of all classes talk.

Lynch takes Gifford’s basic road caper plot but imbues it with real moral and psychological depth. He also wrote a much more satisfying happy ending.

Lynch uses two techniques to deepen Gifford’s narrative.

First, he intercuts statements from Lula and her mother with flashbacks that indicate that they are lying, deceiving themselves, or both. This adds mystery, suspense, psychological complexity, and the satisfying feeling of being let in on secrets.

For instance, at one point Lula recounts how when she was 15, her mother told her she should learn the facts of life. When Sailor replies, “But I thought you said your uncle Pooch raped you at 13.” Lula admits this is correct but denies her mother knew it. The flashback, however, indicates her mother did know. Lula then reports that uncle Pooch—not really an uncle but one of her father’s “business associates,” i.e., a criminal—died in a car accident a few months later. But there’s a strong implication that Marietta had Pooch killed. Later, we learn that he had impregnated Lula, and the child had been aborted. But both Lula and Marietta either are lying about some aspects of these events, or they have edited them out of their memories.

Second, Gifford’s characters and the world they inhabit are entirely profane. But Lynch adds a religious dimension to the film—but only the sort of religion that could appear to feral Americans in the dregs of the Kali Yuga: a movie.

Religions use myths to create meaning and bring about moral transformations. In Wild at Heart, the overarching myth is The Wizard of Oz. But even though it is merely a profane simulacrum of a religion, it still performs the same functions, helping Sailor and Lula make sense of the world and giving Sailor the courage to do the right thing in the end.

Where does the movie’s title come from? At one point, Lula says despairingly, “This whole world’s wild at heart and weird on top.” What does it mean to be “wild at heart”? Longtime readers will know immediately where I am going with this.

I find Plato’s tripartite psychology to be genuinely helpful in understanding this film. In Plato’s Republic, Socrates argues that the human soul has to be distinguished into three distinct and irreducible faculties: desire, which seeks such necessities as food, shelter, sex, and self-preservation; reason, which seeks truth; and spirit (thumos), which seeks honor. Plato associates reason with the head, desire with the belly, and thumos with the chest, which is where we feel pride and anger. Thumos is wildness of heart.

Thumos is the capacity to passionately identify with and love things that are one’s own—one’s self-image, one’s own family, one’s own friends, one’s own nation, etc.—and to defend them when they come under attack from people with conflicting partialities.

Thumos is often translated as “spirit,” which makes sense if we understand it as “team spirit” or “fighting spirit.” The Greeks associated thumos with anger, for we are upset when we or those we love are dishonored.

Thumos is also associated with self-sacrifice, since fighting over honor risks death. This is how we know that thumos is different from desire. Desire aims at self-preservation. But thumos is willing to risk self-preservation for honor.

Socrates suggests that we can differentiate types of men based on which part of the soul wins out when different parts come into conflict. A man ruled by honor follows it, not reason and desire, when they come into conflict. Whenever men fight even though fear or calculation tell them to retreat, they are ruled by thumos. The thumotic man prefers death to dishonor. The man ruled by desire follows desire rather than thumos or reason when they conflict. Drug addicts, for instance, continue to indulge their addictions, even when reason and honor forbid them. The man ruled by reason follows reason whenever it conflicts with desire or thumos. Thumos may urge one to fight against hopeless odds, but reason can say no. Desire may urge one to excess, but reason can impose measure.

Sailor Ripley has strong appetites for sex, drink, and cigarettes. But he is primarily ruled by thumos, which becomes apparent in the first scene. He and Lula are leaving a dance when Sailor is approached by a black man named Bob Ray Lemon, who begins verbally picking a fight with the intent to stab Sailor. When Sailor realizes what is going on, he says “Uh oh.” But he’s clearly not worried about his own safety. He’s signaling that Lemon is crossing a line. When Lemon pulls out his switchblade, Sailor goes into full berserker mode, repeatedly slamming Lemon’s head into a rail and then into the floor, finally hurling his corpse against the wall, its brains spilling onto the floor. Sailor’s reaction clearly set aside all considerations of self-preservation or likely consequences. Reason and desire were totally overwhelmed by thumos.

After spending 22 months in jail for manslaughter, Sailor is released and reunited with Lula. Fearing the interference of Lula’s mother, though, the couple decide to break Sailor’s parole and head to California by way of New Orleans. One night as the couple are passing through Texas, they encounter an accident scene. Two young men are dead. Suddenly a badly injured girl staggers out of the darkness. Sailor and Lula both rush to her aid. They have to take her to the hospital. It is simply the right thing to do. But doing so ensures an encounter with the police, who might learn that Sailor has broken parole. Sailor sees this immediately, but given the choice between following self-interest and helping a gravely injured human being, he does not hesitate to help. When the girl dies in front of them, there is no point in risking discovery, but at this point, Sailor and Lula have less than $100. Practically every other character in this movie is a sociopath whose first instinct would be to rob the dead, but it does not occur to Sailor or Lula.

Another characteristic of thumotic individuals is the value they place on personal loyalty. Sailor speaks fondly of his public defender, who stood by him, but of course the most striking loyalty in the film is between Sailor and Lula. Sailor says that Lula “stood by me after I planted Bob Ray Lemon. A man can’t ask for more than that.” And the loyalty is mutual, for it is quite risky to resume his affair with Marietta Fortune’s daughter.

As the film unfolds, though, it is clear that Lula’s loyalty is the stronger, for Sailor is infected with individualism. Sailor’s trademark is his snakeskin jacket, which he says is for him “a symbol of my individuality and my belief in personal freedom.” Snakes, of course, are low-down, cold-blooded creatures associated with the devil and original sin. Snakeskin is something snakes slough off from time to time, so it is a nice symbol of the individualist who sloughs off relationships and responsibilities in the name of freedom. This is precisely what Sailor tries to do at the end of the movie.

Lula says she has heard the line about the jacket symbolizing individuality and personal freedom “about fifty-thousand times.” Perhaps Sailor is just repeating an advertising slogan, in which case he is actually displaying his lack of individuality and personal freedom. Sure enough Sailor repeats the line in the very next scene, where he picks a fight with a punk who started dancing with Lula. (Uh oh—thumos again.) The punk looks Sailor over and declares “You look like a clown in that stupid jacket.” When Sailor tells him its meaning, the punk simply responds “Asshole.”

And although the punk is supposed to be an idiot (he appears in the script as Idiot Punk) he is completely correct. We all look like clowns clad in our symbols of individuality and personal freedom. Individualism makes snakes—and assholes—of us all.

The great moral transformation of Wild at Heart is when Sailor finally sloughs off the individualist snakeskin and becomes a loyal, loving family man. A decent society educates its citizens both intellectually and morally, helping them overcome the selfishness and hedonism of childhood and the wildness of adolescence to become responsible and rational adults. But Sailor didn’t have much “parental guidance,” and the whole of liberal-individualist-capitalist society works to keep him—and us—in a permanent state of adolescence.

Neither Sailor nor Lula is particularly rational. Lula’s mind seems to move by association rather than reason. As Sailor puts it “the way your head works is God’s own private mystery.” When Lula refers to the world as “wild at heart and weird on top,” the words “on top” could just mean “in addition.” But they could also be in keeping with the physical association of wildness and the heart: wildness is to weirdness as the heart is to the head—“on top.” Thus Lula could be referring to her own proud and irrational character as well, for she is very much a citizen of this world.

Sailor himself is not too strong in the reasoning department, either, but he at least recognizes the necessity of making better decisions. At one point he declares, “Lula, I done a few things in my life I ain’t too proud of, but I’ll tell ya from now on I ain’t gonna do nothin’ for no good reason. All I know for sure is there’s more’n a few bad ideas runnin’ around loose out there.” (Lynch then cuts to Marietta Fortune, in full-blown psychosis, to the terrifying sounds of Krzysztof Penderecki’s Kosmogona.)

At another point he promises Lula that he is not going to let things get any worse. Then he promptly lets himself get talked into an armed robbery, which costs him six years in prison and nearly got him killed. When he is released, he returns to Lula and their son, whom he has never met, but then chickens out and leaves. As he returns to the train station, he is surrounded by a multiracial gang of toughs. He stops, lights a cigarette, and asks “What do you faggots want?” It’s thumos getting the best of him again.

He is duly decked. But in the end, it is not reason that saves him but a vision of Glinda the Good from The Wizard of Oz, who tells him, “Lula loves you . . . If you are truly wild at heart, you’ll fight for your dreams . . . Don’t turn away from love, Sailor . . . Don’t turn away from love . . .” If the Sailor Ripleys of the world had only reason to guide them, they’d be pretty much doomed.

The character that sets the whole story of Wild at Heart in motion is Marietta Fortune, brilliantly portrayed by Diane Ladd. Everyone else just reacts to her. David Lynch is a master of creating villains with a touch of the diabolical, of superhuman or supernatural evil: Frank Booth, Mr. Eddie, the Mystery Man, Leland Palmer, Killer Bob, etc. And who can forget his version of Baron Harkonnen in Dune?

But Marietta Fortune is Lynch’s only female Big Bad, and she’s just one of Wild at Heart’s huge cast of villains: Marcello Santos, Mr. Reindeer, Bobby Peru, Perdita Durango, and the trio of Reggie, Dropshadow, and Juana. In fact, there’s only one unambiguously decent character in the whole film, the detective Johnny Farragut, played by Harry Dean Stanton. Sailor and Lula are both too immature to be good. The overabundance of villains is actually a problem, for Wild at Heart is simply too dark and too violent for many people to enjoy wholeheartedly.

As Wild at Heart unfolds, flashbacks take us further and further into the past, and at every level we find Marietta Fortune pulling the strings. In Lula’s eyes, her mother is the Wicked Witch of the East in The Wizard of Oz. It was Marietta who paid Bob Ray Lemon to kill Sailor. She did it because she discovered that Sailor had been a driver for her sometime boyfriend and business associate Marcello Santos (J. E. Freeman). One night Sailor was waiting in Santos’ car outside the Fortune house when it went up in flames. It turns out that at Marietta’s bidding, Santos had doused her husband Clyde (Lula’s father) with kerosene and struck a match. When Sailor got out of jail and ran off with Lula, Marietta put both Santos and her current boyfriend, detective Johnny Farragut, on their trail.

There was just one problem. Santos’ condition for helping was to kill Johnny Farragut, whom he regards as a danger to his and Marietta’s criminal dealings (probably drugs) with a Mr. Reindeer of New Orleans. Marietta says no but realizes that Santos might well do it anyway. But she doesn’t warn Farragut because she can’t bring herself to admit to him that she broke her promise not to call Santos.

It is classic narcissist behavior. Marietta’s entire life is about projecting bland Southern gracious living clichés. She can’t admit or take responsibility for her errors without compromising her carefully crafted image. The conflict between her fear for Johnny and her inability to admit error leads to a bizarre and hilarious psychotic episode where she in effect commits symbolic suicide, cutting her wrists and throat with lipstick (one of the tools of maintaining her image), then painting her face with it. At that point, she calls Johnny and tells him she has made a terrible mistake. But she refuses to tell him about it on the phone, telling him she will fly to New Orleans and tell him in person the next day. Of course this leaves Farragut in grave danger and probably cost him a night of sleep. Then she vomits in the toilet and begins laughing. The whole drama of death and resurrection has been a catharsis. How does Lynch come up with this stuff?

When Marietta and Johnny meet the next day for dinner, Marietta again refuses to confess and decides that she will just get Johnny out of harm’s way by getting on the road that night. But when he returns to his hotel room, he is kidnapped then murdered by three horrifying thugs dispatched by Santos and Mr. Reindeer. At the end, though, Farragut only feels compassion for Marietta. It is genuinely tragic. He is a good man brought down because he was utterly blind to the depths of Marietta’s deceitfulness and manipulation.

Marietta’s reaction to Farragut’s disappearance is classic. She refuses to call the police, because that would require admitting the true nature of the problem—and also, she probably has lots of unfinished business with the police. When she is given a note, obviously left by the kidnappers, that Johnny has “Gone fishing with a friend, and maybe buffalo hunting,” she immediately interprets it in a face-saving way. He was not kidnapped because of her doing. He was a coward who fled because he was incapable of a serious relationship. When Santos shows up, it is pretty much obvious what has happened, so again to save face, she basically demands that Santos to lie to her, which he gladly does. Marietta then cheerfully pivots to Santos, who will now be her partner in tracking down Sailor and Lula. It is a truly breath-taking portrait of how a malignant narcissist operates. She will pile up lies and corpses without end, as long as she maintains her positive image.

One villain like Marietta is really enough for a film, but in Wild at Heart there are two. Halfway through the film, Sailor and Lula bump into Willem Dafoe’s Bobby Peru (“Just like the country”) in Big Tuna, Texas. Peru has been dispatched by Santos and Reindeer to kill Sailor. Bobby Peru is one of the most viscerally repellent characters ever brought to the screen. That’s a teaser, not a spoiler.

The mysterious Mr. Reindeer (played by W. Morgan Sheppard) is another fascinating study. He’s a man entirely ruled by his appetites. When we first encounter him, he’s wearing a tuxedo, sitting on a toilet, drinking tea, and watching a little striptease in his bathroom. He’s just an expensively upholstered tube. He seems to live in a brothel, surrounded by attractive young women. The madame warns them sternly that they are there to show Mr. Reindeer a good time. “Do not bring misfortune upon yourselves.” In another scene, he is flanked by two topless bimbos talking about a stolen comb. One of them holds a tray with a bottle of Pepto Bismol on it. In yet another scene, he is at a dinner party, surrounded by well-dressed whores, but he only has eyes for Grace Zabriske’s Juana, a twisted, crippled grotesque (one of Johnny Farragut’s killers).

Beginning with the title sequence—an extreme closeup of a match flaring up, followed by a vast, swirling vortex of flames, to the sumptuous opening strains of Richard Strauss’ “Im Abendrot”—Wild at Heart is one of Lynch’s most sensuously beautiful movies: a screen as wide as America filled with strikingly composed images filmed in a way that imbues seedy bars, cheap hotels, and bleak land- and cityscapes with a voluptuous shell pink or sunset or neon luster.

Although I would have preferred more original music by Angelo Badalamenti, who composed the unforgettable score of Twin Peaks, Lynch’s choices cannot be faulted, especially his selections from Strauss and Penderecki and Chris Isaak’s haunting and iconic “Wicked Game” and “Blue Spanish Sky.”

I have grown so fond of Wild at Heart that I am frequently surprised at the strong negative reactions of people to whom I have introduced it. I hope I can do a better job of preparing you. Because Wild at Heart does have its flaws.

For instance, Lynch loses a lot of people early on, in the scene with the Idiot Punk at the rock concert. The film veers into bizarre fantasy when Sailor stops the concert with a hand gesture, humiliates the punk, and then turns the speed metal band Powermad into a backup group while he croons Elvis’ “Love Me” to an audience of screaming, swooning females. Are we supposed to believe this is possible for a guy who just got out of jail and who, even if he did know the band, could not have rehearsed with them? People who routinely suspend disbelief in vampires and space travel throw up their hands in disgust. But you just have to be patient.

Beyond that, Wild at Heart is just a bit too weird on top. There are eccentrics, cripples, and freaks at every turn, and a lot of them have nothing to do with the plot.

Finally the film is really too violent and gross: sadistic murders, including a man lit on fire and two exploding heads, bloody gunshot wounds, a severed hand (you’ll laugh in spite of yourself), two bloody car accidents, the rape of a 13-year-old-girl, an abortion, what basically amounts to the rape of the same woman at 20, while she is pregnant, during which she has an orgasm, etc.

There were three exploding heads in the first cut, but the murder of Johnny Farragut in the middle of the film was so gross that 80 people walked out of the first test screening—100 walked out of the second screening—so Lynch cut it. For the sake of the people around him, I hope David Lynch saves all of his darkness for the screen.

Viewers draw the line in different spots, but virtually everyone who watches this movie thinks “This is too much”—too much weirdness, too much violence, too much blood—well before the final frames. Lynch described Wild at Heart as “a picture about finding love in hell,” but for most people there’s too much hell there to be redeemed by love.

My answer, though, is that these are problems with our world, not with Wild at Heart. And because the movie dives so deep into darkness, the ending is all the more satisfying.

I have watched Wild at Heart more than 20 times, but in the last viewing before writing this, I realized that I had never before watched it without wincing—closing my eyes or looking away—in certain spots. So it took me decades to finally look at every frame of this, my favorite David Lynch film.

I realize I’m not really selling this here. So let me end with one more try.

David Lynch has not made many films, and Wild at Heart falls somewhere in the middle of the pack. But Blue Velvet is certainly the paradigmatic “Lynchian” film: an innocent young man leaves the garden of childhood naïveté, encounters diabolical evil, finds his strength, and triumphs over it in the end—with all the bizarre touches we expect from Lynch.

In Wild at Heart the protagonists aren’t that innocent, and there’s a whole lot more diabolical evil to endure before the happy ending. The same moral order is there, but it is distant. The horror is far more prevalent and oppressive. But of all Lynch’s other works, Wild at Heart is still the closest to the paradigm of Lynchian perfection, and that should count for something.

Does Wild at Heart have a political message—or at least a political lesson it can teach us? Yes, and it is a conservative one. First, it is a very bleak portrayal of the desire-dominated world created by liberal individualist snakeskin salesmen: a world swarming with criminals and freaks and awash in substance abuse, sexual libertinism, and obnoxious music. It is a veritable Garden of Earthly Delights.

We sympathize with Sailor and Lula, and we see that they have decent sentiments, but they were so poorly nurtured and educated that they might have been better off raised by wolves. Sailor didn’t have parental guidance because both his parents died while he was a child of cigarette- or alcohol-related illness, and Lula was raised in the midst of a gang of criminals, one of whom raped her at the age of 13.

Furthermore, neither Sailor nor Lula is particularly good at reasoning, so their desires and their thumos keep getting them into trouble, and in the modern liberal democratic wasteland trouble abounds. Lynch clearly believes that there is a moral order to the world. Sailor and Lula are just too thick to know it by reason.

But the moral order can capture their imaginations, shape their sentiments, and set them off in the right direction in the guise of a narrative, namely The Wizard of Oz. In the wasteland, the only myths we have are movies. When the moral order clothes itself in myths, we have religion.

Yes, Wild at Heart is a religious film. Only magic can redeem these characters, and only Christian or post-Christian sentimentalists would want to. In truth, inadequacies of nature and nurture doom them, and their son, to just more of the same.

Yes, Wild at Heart is grotesque and obscene. But religious art has long employed the grotesque and obscene. Just look at Bosch.

Thus Wild at Heart’s ultimate message is: Liberalism is the road to hell, not paradise—and only a Good Witch can save us now.

Source: https://www.unz.com/tlynch/david-lynchs-wild-at-heart/ [7]