Dancing in the Dark:

Bruce Springsteen & the Betrayal of Blue-Collar America

Posted By

Fenek Solère

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

Lights out tonight

Trouble in the heartland . . .

–“Badlands” (1978)

I was sold on Springsteen the moment I first heard the mournful wail of his harmonica as he began to sing “The River”:

I come from down in the valley

Where mister when you’re young

They bring you up to do like your daddy done

Me and Mary we met in high school

When she was just seventeen

We’d ride out of this valley down to where the fields were green

We’d go down to the river

And into the river we’d dive

Oh down to the river we’d ride

I sat transfixed before the television, watching this thin young man from the New Jersey shoreline standing alone before the microphone, arms dangling in a crumpled sports jacket, black slacks twitching, his reedy voice trembling with emotion as he poured out his heart on the floodlit stage:

I got a job working construction for the Johnstown Company

But lately there ain’t been much work on account of the economy

Now all them things that seemed so important

Well Mister they vanished right into the air

Now I just act like I don’t remember

Mary acts like she don’t care

But I remember us riding in my brother’s car

Her body tan and wet down at the reservoir

At night on them banks I’d lie awake

And pull her close just to feel each breath she’d take

Now those memories come back to haunt me

They haunt me like a curse

Is a dream a lie if it don’t come true

Or is it something worse?

These were powerful lyrics that immediately resonated with someone like myself, surrounded as I was by a rapidly deindustrializing economy, a region that had just witnessed the gates to its coal mines being locked forever, its steelworks scrapped and factories boarded up along the length and breadth of valley towns that were choked with squalid, back-to-back housing. These were whole communities built on fossil fuels with long traditions of manufacturing, much like those Springsteen describes in his 1995 song “Youngstown”:

Taconite coke and limestone

Fed my children and make my pay

Them smokestacks reachin’ like the arms of God

Into a beautiful sky of soot and clay

Here in Youngstown

Here in Youngstown

Sweet Jenny I’m sinkin’ down

Here darlin’ in Youngstown

Because that was my world, too, once lit by blast furnaces like lanterns in the sky, which had now been turned into a post-industrial wilderness of skeleton machinery that filled my horizon like dead dinosaurs, along with bleak, stone-clad, two-up-two-down homes, nestled in the bald shadow of denuded hills. These were one-horse towns filled with somnambulist mothers haunted by memories of an avalanche of black slurry that buried their kids, and the faint tint of oil and asbestos forever hovering in the cold, damp wind.

So when I dropped the needle on the vinyl and heard this American kid scream:

Badlands, you gotta live it every day

Let the broken hearts stand

As the price you’ve gotta pay

We’ll keep pushin’ till it’s understood

And these badlands start treating us good

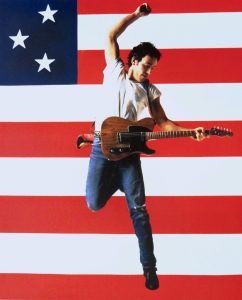

. . . or later when, at the height of his commercial success, framed by the stars and stripes and with a red cap sticking out of the rear pocket of his jeans, I listened to him screech:

Born down in a dead man’s town

The first kick I took was when I hit the ground

End up like a dog that’s been beat too much

Till you spend half your life just covering up

I thought he was singing about me and people like me, as well as those born and bred in the American rust belt and the flyover states, living without privilege and the advantage of affirmative action programs. These are working men and women paid by the hour, who make their way by having to save every day to get an education, pay the rent, keep up with the mortgage, and make good on the down payment for the car. Like Steinbeck’s Tom Joad, who Springsteen penned a eulogy for in the mid ‘90s, these folks were falling victim to the vulture capitalism of rampant globalization that the songster speaks of in the lines:

Shelter line stretching ’round the corner

Welcome to the new world order

Families sleeping in the cars in the southwest

No home, no job, no peace, no rest

And I got angry and wanted to rebel. Hand in hand with my girl, walking down rain-splattered, shuttered streets, I would whistle to the tunes Springsteen played:

In the day we sweat it out on the streets of a runaway American dream

At night we ride through the mansions of glory in suicide machines

Sprung from cages out on highway nine,

Chrome wheeled, fuel injected, and steppin’ out over the line

H-Oh, Baby this town rips the bones from your back

It’s a death trap, it’s a suicide rap

We gotta get out while we’re young

‘Cause tramps like us, baby we were born to run

Both of us were deluding ourselves that “[t]ogether we could break this trap, we’ll run till we drop, baby we’ll never go back.” We were living in a mirage of images The Boss concocted from a patchwork of hackneyed Americana: “The screen door slams, Mary’s dress waves, like a vision she dances across the porch as the radio plays (“Thunder Road”) . . . Wendy, let me in, I wanna be your friend, I want to guard your dreams and visions, just wrap your legs ’round these velvet rims, and strap your hands ‘cross my engines (“Born to Run”) . . . And the hungry and the hunted, explode into rock ‘n’ roll bands, that face off against each other out in the street, down in Jungleland” (“Jungleland”).

These were youthful fantasies of the mythical American dream that climaxed in the biting sarcasm of “The Promised Land”:

I’ve done my best to live the right way

I get up every morning and go to work each day

But your eyes go blind and your blood runs cold

Sometimes I feel so weak I just want to explode

Explode and tear this whole town apart

Take a knife and cut this pain from my heart

Find somebody itching for something to start

And that is how I felt, too. I had been expelled from school and had empty hours on my hands, watching the down-bound trains go by, and listening to the old boys in the run-down bars and workingmen’s clubs talking about their glory days – the last few manual laborers with meaningful jobs, who were working on the highway by laying down the blacktop. I would sit next to Caroline in the Queens, sipping black coffee and smoking Marlboros, fantasizing about being Sissy Spacek and Martin Sheen from Terence Malik’s 1973 movie Badlands. I would flick through the pages of Kerouac’s On the Road and try to pretend we understood the hidden meanings behind William Burroughs’s Cities of the Red Night and The Place of Dead Roads, while getting off to Carl Orff’s “Gassenhauer,” and the sparse, strummed melancholia of Springsteen’s 1982 album, Nebraska, whose title track was a blood-curdling nihilistic yell of murderous intent:

Saw her standin’ on her front lawn just twirlin’ her baton

Me and her went for a ride sir and ten innocent people died

From the town of Lincoln Nebraska with a sawed-off .410 on my lap

Through to the badlands of Wyoming I killed everything in my path

I can’t say that I’m sorry for the things that we done

At least for a little while sir, me and her we had us some fun

And given the disposition of his blue-collar constituency and the harsh economic and cultural storms they have weathered for decades, one can imagine my disappointment when I noticed the ever-increasing proliferation in Springsteen’s songs of Dylanesque side-bars into the realms of virtue-signaling and political correctness. Where, I asked myself, were my guru’s words of condemnation for the pandemic of black-on-white crime sweeping the country; the deterioration of cities like Baltimore and Detroit to Sierra Leone-level civilizational standards; the off-shoring of millions of factory jobs to places like Mexico and the trade imbalances with cheating China; the apartheid of affirmative action; Hillary Clinton’s election machine playing fast and loose with the basic tenets of democracy; and the excesses of MS-13.

Instead of highlighting the death of women like Kate Steinle, a symbol of the victimization of white womanhood, who was murdered by illegal Hispanic migrants, or the sexual exploitation and rape of children by teenage refugees in Twin Falls, Idaho, Springsteen took the easy route, writing songs about miscegenating veterans in Khe Sahn; Le Bin Son, who had apparently fought side by side with the Americans in Vietnam, and who is today naturally a hardworking resident of Galveston Bay, being harassed by ignorant whites; and Amadou Diallo, an innocent Guinean immigrant who died when the police shot him forty-one times. Now, the indignant poet was shouting out lines like:

Soon in the bars around the harbor was talk

Of America for Americans

Someone said “You want ’em out, you got to burn ’em out.”

And brought in the Texas Klan

And:

You’ve got to understand the rules

If an officer stops you

Promise me you’ll always be polite

And that you’ll never run away

Promise Mama you’ll keep your hands in sight

But what about the “Blue Lives Matter Too” campaign and the forty-five, mainly white, officers killed in the line of duty in the first half of 2018? What about the communities forced to integrate against their will, or the countless lives ruined by cocaine and heroin addiction supplied by Puerto Rican and Colombian drug cartels, or the attacks upon and deplatforming of conservative views?

Springsteen’s myopia does not end there. His Academy award-winning song “The Streets of Philadelphia” became an anthem for Kaposi’s sarcoma-afflicted homosexuals:

Saw my reflection in a window and didn’t know my own face.

Oh brother are you gonna leave me wastin’ away

On the streets of Philadelphia.

And, of course, his performances must contain the obligatory nod to Hispanic hipsters like Spanish Johnny, as in one of his earlier songs, “For You”:

Spanish Johnny drove in from the underworld last night

With bruised arms and broken rhythm and a beat-up old Buick but dressed just like dynamite

He tried sellin’ his heart to the hard girls over on easy Street

But they said, Johnny, it falls apart so easy, and you know hearts these days are cheap

And the pimps swung their axes and said, Johnny, you’re a cheater

And the pimps swung their axes and said, Johnny, you’re a liar

And from out of the shadows came a young girl’s voice

Said, Johnny, don’t cry

Puerto Rican Jane, oh, won’t you tell me, what’s your name?

I want to drive you down to the other side of town

Where paradise ain’t so crowded and there’ll be action goin’ down on Shanty Lane tonight

All the golden-heeled fairies in a real bitch-fight . . .

And let’s not forget those exotic Latina beauties in “Rosalita Come Out Tonight”:

Rosalita, jump a little higher

Senorita, come sit by my fire

I just want to be your lover, ain’t no liar

Oh Baby, you’re my stone desire

Can he not hear the calls from the deplorables of “Lock her Up!” and “Build the wall!” resounding in the packed auditoriums every time Trump takes to the stump? Is there any room in his edgy repertoire for condemnation of the sexual predations of Bill Clinton, Harvey Weinstein, and Bill Cosby, or the fact that his welfare-dependent Rosalitas are dropping anchor babies that are bankrupting California, or that his Jennys, Marys, and Wendys are something like twenty-five times more likely to be raped by a black than a white man?

So much for The Boss’s The Deer Hunter and The Indian Runner movie optics; or for inspiring Tennessee Jones’s Deliver Me from Nowhere; or for his subliminal references to Cormac McCarthy’s classic 1979 novel Suttree in lines such as, “But there are no absolutes in human misery and things can always get worse.”

And indeed, they do. Springsteen played at a pro-Clinton rally in front of thirty-thousand people in Philadelphia on the eve of her election runoff with Trump. He later told Variety, “Yeah, I thought she would have made an excellent president, and I still feel that way, so I was glad to do it.” He said this about a woman who had been hoovering up foreign blood money for the blatantly corrupt Clinton Foundation while supposedly acting as Secretary of State in the Obama administration, and whose flagrantly poor judgment led to the deaths of senior America diplomats and security personnel in Benghazi in 2012.

Surely, in an America where the people who founded and built the nation are on course to be demographically replaced within decades, such a visceral reality must generate enough material for an ingenious songwriter like Springsteen to produce a double-length protest album, rich in social observation, racial and cultural critique, and lyrical hyperbole to match his signature tunes like “Born to Run” and “Born in the USA.” But we all know that is not going to happen, because to even think such things is to “step over the line.”

And he would never do that, schooled as he is in the commercial red-lines laid down by Sony’s CEO, Rob Stringer, the winner of the United Jewish Appeal-Federation of Jewish Philanthropies of New York’s Music Visionary Award, a foundation which is dedicated to “strengthening Jewish communities in New York, in Israel, and around the world.”

So, Bruce, I say to you, you may be a footlights star, charging eight hundred dollars per ticket for your nostalgic ramblings about an America that is fast disappearing in your Broadway talk-shows, but to a discerning admirer like myself, someone who judges a performer not just by his talent, but also by his artistic integrity and honesty in reflecting a society as it truly is and not as some people would have us believe, you fall way short, and are just a shill and a cuck dancing in the dark.