Born-Again Paganism:

Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring

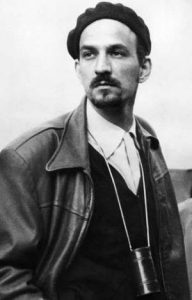

Posted By

Collin Cleary

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

The Criterion Collection’s recent release of a comprehensive Blu-ray collection of the cinema of Ingmar Bergman is an opportunity to re-assess the work of this greatest of Nordic filmmakers. Those who seen little of his work (or none at all) usually have the impression that Bergman’s oeuvre is dark and gloomy, filled with existential angst over the “death of God.” (Indeed, he is often described as an “existential filmmaker.”) At best, this is a half-truth. One can indeed find those elements in Bergman, but there is much more. Bergman’s reputation in the English-speaking world was firmly established by 1957’s The Seventh Seal, which contains some of his most explicit (and, I would say, unsubtle) disquisitions on the death of God. But to describe even this film as “dark and gloomy” is something of a misrepresentation, for it contains scenes that are life-affirming and funny.

Indeed, one can speak of a struggle between two tendencies in Bergman’s cinema. On the one hand, we have the predominantly “gloomy” Bergman, represented by such films as Through a Glass Darkly (1961), Winter Light (1963), The Silence (1963), Persona (1966), Hour of the Wolf (1968), and others. By contrast, we have the (perhaps less well-represented) “optimistic” Bergman of films such as Smiles of a Summer Night (1955), Wild Strawberries (1957), and The Magic Flute (1975). It’s not much of a stretch to refer to the “optimistic” Bergman as exhibiting a kind of pagan sensibility: life-affirming, joyous, and “earthy” (even sometimes quite bawdy).

This sensibility is very much on display in one of the greatest films of Bergman’s later period, Fanny and Alexander (1982; announced as Bergman’s “last film,” though he would go on to direct four minor films, originally shown on Swedish television). Here we find two households set in stark contrast to each other. The first is that of the Ekdahls, a theatrical family. The lengthy depiction of their Yuletide celebrations in the first hour of the film is thoroughly pagan in spirit – though it concludes with a perfunctory reading of the story of the birth of Jesus, during which everyone observes a stiff and obligatory solemnity. The other household is that of the rigid Bishop Vergérus, which is utterly devoid of joy, and even of color.

The gloomy Bergman lives in that latter house. And in Fanny and Alexander the two tendencies of Bergman – the optimistic/pagan and the gloomy – confront each other. And this film helps us make explicit what the “gloom” consists in: it is fundamentally Christian. Almost all the gloominess to be found elsewhere in Bergman stems, in one way or another, from his struggle to deal with his loss of Christian faith, and search for meaning in a Godless universe (this is most apparent in The Seventh Seal and Winter Light). It is not hard to see where this element in Bergman’s character comes from: his father was a prominent Lutheran minister, later chaplain to the King of Sweden. And it was upon his father that Bergman based the character of the sadistic Bishop Vergérus. As to the “pagan” element . . . well, that apparently emerges quite unconsciously, from deep within Bergman’s Nordic soul.

Ultimately, the pagan is victorious over the Christian in both Fanny and Alexander, and, it seems, in Bergman himself. And it is certainly victorious over the Christian in The Virgin Spring (1960), Bergman’s most explicitly pagan film. The Virgin Spring does not rank very highly in retrospectives of Bergman’s work, probably because he did not write the screenplay himself (it was written by Ulla Isaksson). Bergman himself, in later years, did not hold a high opinion of the film: “A wretched imitation of Kurosawa,” he stated in an interview. This is unjust, for in fact it is one of Bergman’s most beautiful and powerful films. The Virgin Spring belongs to a small group of films that I watch only once every few years, as its emotional impact is so intense (others in this category include Fellini’s La Strada and Hitchcock’s Vertigo). If you have never seen this film, I encourage you to stop reading at this point and see it – as there are numerous spoilers ahead.

The film is set in medieval Sweden, and Ulla Isaksson’s screenplay is based on a thirteenth-century Swedish folk-song called “The Daughter of Töre of Vänge” (Töres dotter i Vänga). It was Bergman himself who conceived of the idea of adapting the song into a film. Reputedly, he offered the job of screenwriter to Isaksson because she had written a historical novel (about a witch hunt, set in the seventeenth century), and he felt she would be able to depict medieval Sweden realistically. Isaksson had previously written the screenplay for Bergman’s film Brink of Life (Nära livet, 1958).

The story of “The Daughter of Töre of Vänge” is linked to an actual place in Sweden. As Isaksson tells it (in an essay included in the film’s pressbook [3]):

Even today in Karna churchyard in the County of Östergötland in central Sweden there is a spring which tradition firmly links with the legend. Here the villagers assemble at Midsummer when the woods are green. Here they drink water from the spring, which is considered to have healing properties, and here they make special thanksgiving offers to the church on a specially erected thanksgiving pole. Here they also sing and dance to the folk-song.

All the events, and many of the small details of the folk-song, are present in the film, but Isaksson has embellished them quite a bit. The main character is Per Töre (Max von Sydow), who lives on a prosperous farm with his wife Märeta (Birgitta Valberg) and teenaged daughter Karin (Birgitta Pettersson). Töre and Märeta are devout Christians, the latter even practicing self-mortification. The dialogue implies that the couple have had other children, none of whom survived. As a consequence, they spoil their only daughter.

Several farmhands live on the premises with the Töres and eat with the family. One is an ill-tempered and licentious young woman named Ingeri (Gunnel Lindblom), who happens to be several months pregnant. It is likely even she does not know who the father is. Ingeri envies the spoiled Karin, hating her with a passion. In the first scene of the film, Ingeri is alone, lighting the hearth in the morning as the cock crows. She peers around to make sure no one is listening . . . then calls to Odin. “Odin, come!” is the film’s first line. Ingeri intends to invoke the old god in order to put a spell of revenge on Karin.

At breakfast, Karin is missing, apparently ill in bed. But Töre reminds his wife that this is the day on which Karin was supposed to ride to the church (which is several miles away) to light candles for the Virgin. It transpires that Karin is not ill, but is only being lazy and is uninterested in getting out of bed. Her mother, who obviously adores the child, brushes her hair and dresses her in her finest clothes: a golden shift woven (so it is claimed) by fifteen maidens, a fine cloak, and blue shoes. (The film is shot in glorious black and white – by Sven Nykvist, in his first project with Bergman – but the colors of the items are referenced in dialogue, and are the same as mentioned in the original folk-song.)

Karin is a very pretty girl, and despite being spoiled and manipulative (especially towards her extremely indulgent mother), she is innocent and appealing. She is depicted as just coming into the age where she is developing an awareness of her femininity and her power over men. She brags about how many men she danced with the previous night, and later allows a local farmer to flirt with her – up to a point. Karin feels superior to Ingeri in that, for all her wiles, she is still a virgin. “I’ll be a mistress of a house and married with honor [when I become pregnant],” Karin tells her. “No man will bed me without marriage.”

It is decided that Ingeri will accompany Karin when she rides to church with the candles. Before setting off, Ingeri packs a lunch for Karin. She takes a large piece of flat bread and divides it in half with a knife. Then, noticing a toad on the floor, she snatches it up, traps it between the two pieces of bread, and puts it in Karin’s knapsack. This is either a simple act of malice, or (in Ingeri’s mind) part of the spell she has cast on Karin. Ulla Isaksson comments as follows: “The toad, which she in a moment of hate had stuffed into her [foster] sister’s provisions for the journey, becomes, for those who insist on interpreting everything psychologically, a symbol for her evil desires, but is really a symbol, according to ancient tradition, for death and the devil.”

After a tender farewell to her father, Karin rides off with Ingeri, each girl on her own horse. They ride past a river and then into the forest. Presently, they come to a small millhouse sitting over a stream. The sole occupant of the house emerges as he hears the two girls approach. He is an old, one-eyed man. (This is handled subtly and is not immediately obvious: one eye appears normal, while the other is solid black, as if he has a black stone or black glass orb in the socket.) Bergman introduces this scene with a closeup of a large raven cawing in a tree. It is obvious that we are now in the presence of Odin. Ingeri asks him his name. “These days I have no name,” the old man responds.

He helps guide Karin’s horse across the stream. On seeing the old man, Ingeri is seized by a feeling of foreboding. She rushes up to Karin. “Let’s turn back. I can take the candles,” she says. But Karin refuses. She asks the old man if Ingeri can rest in the millhouse until she returns. He consents, and Karin rides on. “In labor?” the old man asks Ingeri. “No, worse than that,” Ingeri responds, watching Karin disappear into the forest, concern in her eyes. It is evident that Ingeri is having second thoughts about invoking Odin, and now fears for Karin.

The old man leads Ingeri inside, where we find the water of the stream rushing through the apparatus of the mill. He invites Ingeri to sit in the high chair that dominates the room, a chair covered in curious carvings. “I hear what mankind whispers in secret,” he says, pulling a table in close. “And I see what it believes no one can see. You can hear for yourself, if you do as I do.” Ingeri looks up to the rafters and suddenly hears what sounds like furious hoofbeats passing over the house. “What thunders outside?” she asks. “Three dead men riding north,” he answers. (A closeup now clearly reveals that he is one-eyed, as he stares intently at her.)

The old man crawls into the seat with Ingeri, evidently fancying her. “It’s a long time since a woman made my seat narrow,” he says. Then he reaches for a box and empties its contents onto the table. It is hard to tell what each of the objects is. “Here is a cure for your suffering. Here is a cure for your woe,” he says, indicating each object. “Blood, course no more,” the old man says, lifting what looks very much like a finger. “Fish stop still in the brook. And you, eagle, in the sky,” he says, handling what appears to be a small bat. Then, strangely, he leans in and grips one of the carved arms of the chair. It depicts a face. Probably a god, but it is impossible to tell which one. “Here is the power,” the old man whispers.

Ingeri is becoming increasingly agitated. “You’ve taken human blood. You’ve made a sacrifice to Odin,” she says.

“I recognized you at once on the path,” he responds. “By your eyes, your mouth, your hands. But you’re afraid. I’ll give you strength.” He means that he recognizes her as a fellow pagan, or practitioner of witchcraft (in that period, it came to much the same thing). He recognizes that she has been up to something, yet is afraid of her own power – of the spell she has cast and (as we shall see) cannot reverse. He wants to strengthen her in her resolve, to help her come to terms with her belief in the old ways. But the old man only succeeds in terrifying Ingeri. She rushes out of the house and, forgetting her horse, runs into the forest in search of Karin. The old man watches her departure ruefully, as the raven caws again in the background.

We now come to a part of the film that is very difficult to watch. Karin happens upon three herdsmen – two men and a young boy of about eight years – and their small herd of goats. The herdsmen are never named in the film, and are referred to in the screenplay as Thin Herdsman, Mute Herdsmen, and Boy. It is immediately obvious to the audience that the two men are consumed with lust on first laying eyes on Karin, but she, of course, is innocent concerning such matters. She offers to stop and share her lunch with the three, blissfully unaware that they do not mean well. The mute herdsman croaks grotesquely, and we learn from his brother that some “wicked men” cut out his tongue. This was obviously in punishment for some crime, and the three brothers are probably bandits. But Karin suspects nothing.

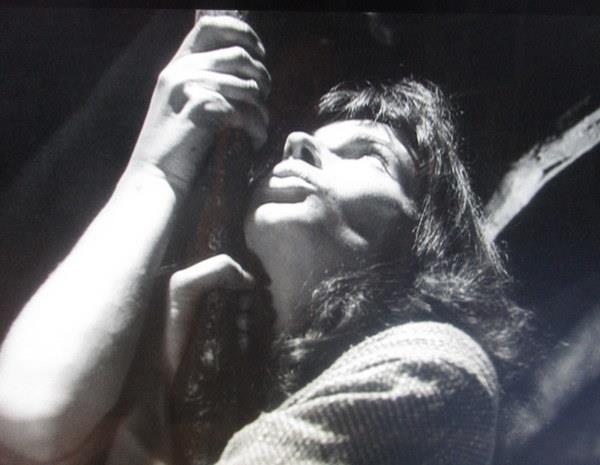

Indeed, she only begins to get an uneasy feeling after she divides the bread and the brothers devour it before grace has been said. Karin spins out a silly yarn about how her father is a fabulous king, and her mother a great queen with so many keys she can’t wear them on her belt. The brothers roar with laughter. But it is apparent that they are laughing at her innocence – an innocence they will soon violate. After satiating themselves on the bread, they fall silent and begin to inch closer and closer to Karin. As the thin herdsmen praises her body, she finally realizes what their intentions are. Birgitta Pettersson’s performance in this scene is remarkably affecting.

Unbeknownst to Karin and the men, Ingeri has now caught up with her mistress and is watching from behind a hill a few yards away. It is clear from her expression that she has realized the peril that Karin is in. In a touching and pathetic gesture, Karin, in her terror, offers the boy her other loaf of bread, then grabs a small goat and clutches it to her breast for comfort. When she looks down at its ears, she realizes that the animal bears the mark of one of the farmers in the area – and she announces this to the brothers. Of course, this seals her fate. Now they cannot allow her to live, lest she reveal that they are thieves. The little boy drops the bread – and out hops the toad Ingeri had planted inside.

As the brothers move in on her, she calls out, pathetically, “I’m on my way to the church, with the candles for the Virgin.” But, of course, this means nothing to these men. Ingeri watches, growing more and more frantic. She picks up a stone, half intending to run to Karin’s defense, but she lets it fall from her hands. Now the two older brothers fall upon Karin and take turns raping her. I will say no more than that, save that the scene is disturbing and surprisingly graphic. It was considered shocking in 1960, and still is. The reader must judge for himself. I can think of only one other comparable scene in cinema, and that is the rape scene in John Boorman’s Deliverance (1972).

In the end, one of the men picks up a heavy stick and bludgeons Karin to death (off camera). They then strip her of her fine garments, pack them into their bags, and frantically and ineptly try to destroy the evidence of their little picnic. The mute brother stomps on Karin’s candles, breaking them. The two older brothers run off into the forest, leaving the boy to guard the goats. (It is not clear why they leave.) He picks up a piece of the bread and tries to eat it, but vomits instead. Then he crawls over to Karin’s body and piles a shallow layer of earth over her. Is he trying to hide her body, to protect his brothers? Is he showing respect, and remorse for what his brothers have done? Possibly both. Terrified, he runs into the forest after his brothers, abandoning the goats.

There is now a long, slow fadeout and fade-in. The location has shifted back to Töre’s farm, and it is dusk. The three brothers, now on the lam, have arrived there quite by accident, seeking shelter. At this point, the suspense in the film derives from our wondering how (or whether) Töre and his wife will discover that the three herdsmen have killed Karin. At the gate, they speak with Töre, who is clad in a long, warm cape. They claim to have come from the north, where the winter has been hard and people are starving. They seek shelter for the evening. Töre, with his usual generosity, says that they can sleep inside, as there will be a frost that night.

Töre and his wife are, of course, anxious about Karin, wondering why she has not yet returned. They assume that she must be staying in the village and will return in the morning. The entire household now sits down to dinner, and the herdsmen are invited to partake. The boy, however, is still too traumatized to eat, and at one point spills his stew all over the table rather than consume any of it. It is clear that his brothers are worried that the boy’s behavior will give them away.

After dinner, the brothers are invited to sleep in the hall and told they may keep the fire going. Frida, an old woman who works for the family, puts the boy to bed, showing him a good deal of tenderness and admonishing him to say his prayers. No sooner has he been tucked in, however, than an older male farmhand looms in and terrifies the boy with a long description of the punishment of sinners in hell (this sort of lengthy monologue, shot entirely in closeups, is a staple of Bergman’s films). After this, the brothers are left alone in the hall to sleep.

It is no surprise at all that, a little while later, Märeta hears the boy cry out in the night. She had been alone with Töre, agonizing over Karin, telling him repeatedly, “She’s all I have.” Märeta leaves their bedroom and enters the hall to check on the boy. She finds the two older brothers wide awake and anxious, watching the boy, who still lies in bed. Märeta seems to sense that something is amiss. She tells them that she thought she heard the boy cry out. The thin herdsman lies and says that it was an owl. Märeta goes over to the boy, who is either asleep or pretending to be, and gently caresses his head.

Just as she is about to leave them, the thin herdsman suddenly presents her with Karin’s golden shift! He concocts a story about its having belonged to their dead sister, and offers to sell it to Märeta. She recognizes the garment immediately, however. Märeta takes the shift from him, and stares down at it for a very long time. Slowly, she lifts her eyes to the herdsman and says, with great dignity and control, “I must ask my husband what would be a just reward for a garment such as this.” Märeta steps outside, still holding the shift, and closes the heavy door behind her. She sinks down onto the stone threshold and begins to weep, holding the shift against her face. Then she lifts her head, and we can see from her expression that an idea has formed in her mind. Quickly, she gets up and lifts the heavy bar into place before the door, trapping the herdsmen inside.

Märeta goes to Töre with the shift and tells him everything. He shows no sign of grief (and will not, until the end of the film). Instead, he quickly begins to dress. Opening a nearby trunk, he removes a fine sword. Töre exits the bedroom and descends the wooden staircase outside. In doing so, he finds Ingeri hiding beneath it. At some point, she had snuck back to the farm. Töre angrily pulls her out from under the stairs and demands that she tell him everything she knows. Ingeri does so, confirming that Karin has been raped and killed. Distraught, she blames herself for what has happened. “I willed it,” she says. She confesses that she invoked Odin, and says that the herdsmen were merely possessed by the god. Ingeri insists that it is she who is really at fault. Töre ignores this and orders her to prepare a bath for him, while he goes to fetch birch twigs.

There now follows one of the most dramatic and memorable scenes in the film. Töre approaches a young birth tree, standing quite alone in a field. Instead of merely chopping off its branches, he throws himself at the tree, twisting it and pulling violently until it has been uprooted. It is as if he hates the young tree for living, while his own child is dead. And the scene is a portent of things to come, for not even the boy will escape Töre’s wrath. Once the tree has been uprooted, he removes its branches with his sword.

Töre now bathes in what appears to be a sauna house. With Ingeri sitting nearby, Töre vigorously douses himself in water from a large metal pot, and beats himself with birch branches. (Max von Sydow appears nude, shot from behind.) It is a curious scene. Ulla Isaksson comments as follows: “The steam bath he takes to prepare himself for revenge has no ritual background, but is symbolically used in the film to represent his need to cleanse himself before the revenge – such cleansing is both a Christian and pagan practice before making religious offerings or pagan sacrifices.” After the bath, Töre orders Ingeri to bring him the butcher’s knife (or “slaughtering knife”).

Armed with said weapon, Töre now quietly enters the hall, accompanied by his wife. The herdsmen are all asleep in one straw bed, the elder brothers snoring. Töre gazes down at them, then sits in his high seat and plunges the knife into the table before him. Still, the brothers do not wake. Finally, in exasperation, Töre goes to the bed and shakes them. The mute herdsman immediately jumps up, a knife in his hand. Töre pins him against the high seat, and plunges his butcher’s knife into the man’s neck, killing him. The thin herdsman, meanwhile, has rushed to the door in an attempt to escape. Töre lunges at him, and the man then tries to climb up a thin pole and out the smoke hole in the roof. But Töre grabs him, and the herdsman falls onto the fiery hearth. There, Töre gets hold of the man and literally squeezes him to death.

Then, he turns his attentions to the youngest of the trio. In terror, the boy rushes to Märeta, who embraces him. At this point, when I first saw the film, I was expecting that the boy would be spared. When Töre approaches him, Märeta cries “No!” But Töre ignores her and grabs the boy. He lifts him up over his head and flings him with great force against the wall. The impact kills the boy. Töre examines the body, but shows no remorse. Then, he stares at his own hands, as if in wonder – or horror – at what they have just done. “We must find Karin,” he says to Märeta.

At dawn, the entire household ventures into the woods, marching to the spot where Karin was killed. Ingeri guides them. When they come to the stream, we again see the raven cawing in a low-hanging tree branch. But there is absolutely no sign of the old, one-eyed man. Töre takes the lead, moving at a frenetic pace. Märeta grabs at him, but he takes almost no notice of her. “I loved her more than God himself!” she cries. She confesses that she began to hate Töre for the affection that Karin showed him. “The guilt is mine,” she says. “Only God can judge,” Töre replies.

At last, they come to the spot where Karin’s body still lies, undisturbed. Märeta falls to her knees and clutches her daughter to her breast, weeping. Töre walks a few paces away, and is finally overcome with grief. He drops to his knees and hugs the earth. “You saw it, God,” he cries. “The innocent child’s death and my vengeance. You permitted it. I beg your forgiveness. I know no other way to live.” Then, he makes a solemn promise to build a church of stone on this spot, as penance for his sins.

Töre returns to his wife’s side. Just as they lift Karin from the ground, the earth where her head had lain suddenly opens up, and a spring gushes forth. Seeing it as a miracle, they all fall to their knees. Ingeri is overcome with emotion. She washes her hands and head in the stream, as if cleansing herself of her sins. Then, Märeta takes some of the water into her hands and sprinkles it on Karin’s head. Here the film ends.

The Virgin Spring is fascinating just as a piece of cinema. It is intensely moving, well-acted, and brilliantly photographed. But it is also fascinating for its treatment of the conflict between Christianity and paganism. Iskasson writes of how her screenplay embellishes the original folk-song, stating that the film “has a line of tension running through it, which while it strictly speaking does not come in to the folk-song, springs from the period itself: the tension between Christianity and paganism in Sweden at that time.” She continues:

Sweden had officially been Christian for several centuries by the time the folk-song emerged, but all the time the old gods were worshipped in secret and sacrifices were made behind locked doors here and there throughout the countryside. It is therefore quite understandable for the unhappy foster sister to turn to the old Viking god Odin in her hate for the happy, fortunate sister. She calls on Odin in the old accepted manner to give her sister into his power.

The portrayal of Ingeri’s pagan ways, and – especially – the episode with the one-eyed man, are quite interesting. In truth, however, it is in Töre and his wife that we find the most striking survival (or re-emergence) of the old ways. Near the beginning of the film, we see Märeta pouring hot candle wax onto her wrists so that she might share in Christ’s suffering on the cross. But in the moment she bars the door to the hall, sealing the doom of the herdsmen, she is transformed into a woman of the sagas. When she informs Töre of what the herdsmen have done, he shows absolutely no signs of hesitation or moral confusion. His first instinct, which he carries through to completion without a moment’s wavering, is for vengeance.

We expect Töre to show some sign of Christian charity when it comes to the fate of the boy, but he kills him as he did the others – again, without evincing the slightest bit of doubt about the justice of his actions. Märeta’s own (very brief) defense of the boy is better attributed to her maternal sympathy than to her Christian faith. All of this was quite deliberate on Isaksson’s part. She writes, “The father’s murderous revenge is also of barbaric origin; he takes his revenge as a matter of course and without a moment’s hesitation and is wholeheartedly supported by his wife in this.” (Of course, the revenge is also part of the folk-song, so we can say that there is a pagan, pre-Christian ethos to the original story as well – and that probably no one consciously reflected on this.)

Töre’s repentance in the final scene is inevitable, and it is not insincere. He truly believes that he has sinned and must atone. But we do not for a moment believe that he regrets what he has done. He simply recognizes that he must pay a price for it. Notice that he does not resolve to change his ways. As he says, “I know no other way to live.” When faced with the most significant and terrible event of his life, Töre responds not as a Christian but as a pagan barbarian. It’s the deep truth of his nature – over which is smeared only a thin veneer of Christianity.

Is it the deep truth of all Nordic peoples? Still? We are all waiting (hopefully not in vain) for today’s Swedes to again display the spirit of Per Töre.