The Weltanschauung of Woodrow Wilson as Viewed from the Right

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled2,522 words

As this article goes to print, an eventful century will nearly have passed since January 1919, when the belligerents of what was then called “The Great War” met in Paris to establish treaties between the belligerent nations and to try to create institutions that would sustain the peace. These delegates consisted of the heads of state of the great powers (France, the UK, the US, Italy, and Japan), representatives from entirely new nations (such as Yugoslavia) and nations being reborn (such as Poland), and activists of colonized peoples who were seeking independence, but who did not get it (such as Vietnam). These delegates met for six months. To put this remarkable event in perspective, today it would be unusual for the Prime Minister of England and the President of the United States to meet for more than a few days regarding any matter. However, we also all know today that these peace treaties soon fell apart, and the institutions that were established, such as the League of Nations, likewise failed.

[2]

[2]Surrealist art had its origins [3] on the Western Front of the First World War. Other types of art were also influenced by it. The historian W. Scott Poole [4] has persuasively argued [5] that many horror movies are the result of an artistic coming-to-terms with the destruction wrought by that conflict. For example, Game of Thrones’ White Walkers are remarkably like the army of the dead in the climactic scene of J’accuse [6] (1919), a film which was directed by a French war veteran.

Looking back, it is difficult to even understand today why Europe went to war. There were no clear ideological differences between any of the belligerents. The monarchs of Europe were all related by blood, many quite closely, although it is true that there were a great many jealousies and family feuds. Nevertheless, in August 1914, France, Germany, Russia, Austria-Hungary, and Great Britain could have let sleeping dogs lie.

It is entirely possible that the war aims of the Central Powers were not as irrational or evil as they were made out to be. Consider that, much later in the twentieth century, the former Western Allies of The Great War went to war to defend the geographical boundaries of their former Central Power rivals. For example, during the Yugoslav Wars of the 1990s, Britain, France, and the United States fought for Slovenia and Croatia – the southern border of the Hapsburg Empire, which had fought against the Serbs. And today, NATO troops are guarding an eastern frontier that corresponds to the boundaries of the German Empire after the ratification of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Russia in 1918.

It is difficult not to conclude that The Great War was a tremendous waste of men and resources. The leaderships of the various countries involved blamed impersonal forces for mistakes they themselves made in bringing about the disaster. To make matters worse, they succumbed to what economists call the sunk cost fallacy. The costs of waging the war were so high that no party involved could justify ending it without achieving a total victory – even though, of course, doing so would have kept the costs where they were. The philosophy of the war became go-for-broke across Europe – and in the end, all of Europe was broken.

It is highly debatable who was really responsible for starting the war. Germany ended up taking the blame because they lost. But in a just world, it probably could be proven that Serbia, rather than anyone else, was the reckless, aggressive, terror-sponsoring, and militarized state that was the true culprit. However, there are other factors to consider. The Kaiser didn’t need to give the appearance of issuing a blank check to Austria-Hungary when they gave their ultimatum to Serbia, nor did the Germans need to make any threats against the French. Likewise, the Russians didn’t need to partially mobilize in support of Serbia, which inevitably triggered a German response. And “Belgian neutrality” was not something that Great Britain really needed to defend at all costs.

Recently, I had the opportunity to visit the National World War I Museum and Memorial [7] in Kansas City, Missouri. While looking at the old uniforms, machine guns, and early tanks is an entertaining way to spend an afternoon, what is more interesting is the bookstore on its main level, and the library in its basement. The pantheon of ideas that came out of The Great War is what is truly engrossing. We, today, live in the world that was crafted by these ideas.

The first two “big ideas” that emerged and moved to the forefront were fascism and Communism. Fascism was not defeated by other ideas; instead its various offshoots were defeated by force of arms. Regardless, many of its ideas live on in some form in Europe and other places. Communism was a Jewish intellectual movement that took root in the area of the former Grand Duchy of Moscow and expanded outwards. Communism’s high-water mark was probably when Saigon fell in 1975, but in the following decade, it became clear that the Communist bloc was coming apart. In 1991, Communist ideology was widely believed to have been defeated with the demise of the Soviet Union and its satellite states, even though it lived on in a few isolated pockets. Communism was defeated both in the realm of ideas and in the clear disaster of its application in the real world.

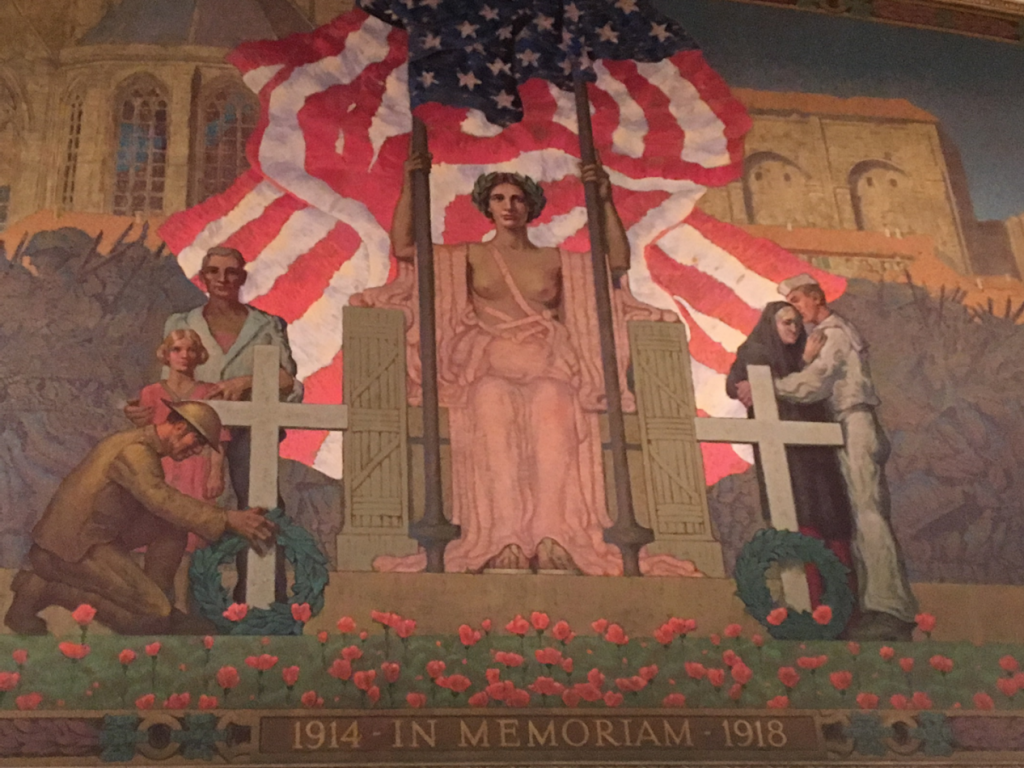

[8]

[8]Bearing in mind that Jesus Christ said, “Why beholdest thou the mote that is in thy brother’s eye, but considerest not the beam that is in thine own eye?”, President Wilson’s Weltanschauung deserves scrutiny. (From a mural at the National World War I Museum in Kansas City.)

But it was the third big idea that was to have the most long-lasting impact: Wilsonian democracy. This ideology doesn’t have a manifesto. The closest thing to a statement of its aims is Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, although with two exceptions (Points Two, free seas, and Three, free trade), all of them are specific to the situation in 1918. Therefore, they aren’t generalized principles like the Beatitudes that work in a broad, timeless sense. The remaining points were fully applied in 1918, such as Points Seven (Belgian independence), Eight (that the occupied parts of France should be liberated), and Thirteen (Polish independence), or else imperfectly applied at best, to put it mildly.

“What can a mere French minister do when associated with Lloyd George, who thinks he is Napoleon, and Woodrow Wilson, who thinks he is Jesus Christ?

–Georges Clemenceau (1841-1924)

Woodrow Wilson was a deeply American man, but by no means can anyone call him a Yankee [9]. His family was of Scottish and Protestant northern Irish ancestry, and Southern to the core. His father was a Presbyterian minister in Virginia. As a child, Wilson was touched by the fires of the US Civil War, but he didn’t fall into the nostalgic morass of the Lost Cause that etherizes so many people. He never argued that the “South was right!” or spit venom at New Englanders. Wilson had deep friendships with Jews, and appointed one to the Supreme Court of the United States – a move that would later result in the displacement of American whites.

Wilson was part of the American Progressive movement, whose roots can be traced back to the Second Great Awakening [10], a spiritual movement derived from American Protestantism which still affects our society today. Domestically, Wilson implemented many of the ideas of this movement, such as Prohibition. Wilson was not what one would today call a religious fundamentalist, believing in the literal truth of the Bible with its dead-end crusades for Young Earth Creationism. Instead, he sought to use Jesus Christ’s ideas to improve humanity’s lot on Earth.

Wilson was a man of the Left who took a great many cues from William Jennings Bryan, who had invigorated the Democratic Party in the 1896 national election and infused that party with a raft of new concepts and policy proposals. Wilson rose to the presidency by an unusual route: he was a Presbyterian academic who later became President of Princeton University. From there, he became Governor of New Jersey, and then won the presidency in the 1912 election. His victory was aided by the fact that the Republican Party had broken apart due to the emergence of Theodore Roosevelt’s Bull Moose Party.

One of Woodrow Wilson’s biographers, A. Scott Berg, speculates that Wilson may have been suffering a series of small strokes during the latter half of his presidency, including during his time at the 1919 Paris conference. This may explain many of his episodes of ill behavior and severe, almost irrational fallings-out with advisors and friends during the conference, but it could just as easily be argued that the strain caused by Wilson’s idealism crashing against the hard realities of the ever-destabilizing Europe was the real culprit.

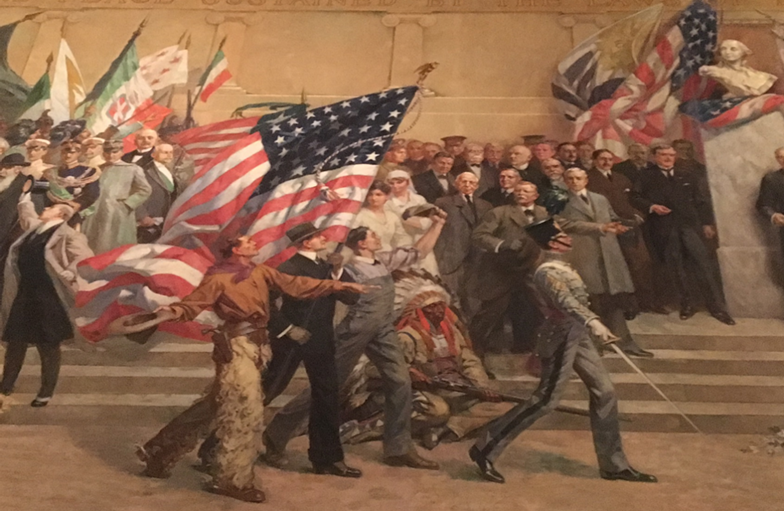

[11]

[11]This is a portion of the Panthéon de la Guerre. Originally, this was a panoramic painting made in France during the war which told a story to audiences by being rotated in a special gallery, accompanied by music and narration. It was acquired by US businessmen in 1927 and exhibited in New York. Eventually, however, the audiences grew smaller and the panorama became unprofitable. It was “restored” in 1956, which actually meant its evisceration in a perfect example of metapolitics. Life follows art, but it is equally true that art follows life. Originally, the central thrust of the panorama was a celebration of France’s accomplishments in the war; however, the painting was altered to make the entry of the United States into the war its center. Even President Harry S. Truman was added during restoration, wearing his US Army captain’s uniform. It is telling that the enthusiastic Americans shown above are not so much armed soldiers as enthusiastic idea-men. The American ideology, first evangelized by Woodrow Wilson, dominated the rest of the twentieth century. The painting eventually fell into the hands of the National World War I Museum.

“Let future generations understand the burdens and blessings of freedom.”

–George H. W. Bush

(One of many American leaders since Wilson who have invoked that slippery word: “freedom.”)

That President Wilson had a new worldview was first recognized by the British at a royal dinner in London on December 27, 1918, which was held in honor of their victory. While the rest of the guests wore medals, gold braid, and jewels, Wilson wore an ordinary black suit. His appearance, wrote historian David Reynolds, was “Cromwellian,”[1] [12] and Wilson made it clear in the speech that he delivered for the occasion that he had an agenda of his own. Generations of Americans have followed Wilson’s Weltanschauung, but his ideas have yet to be critically examined from the perspective of the North American New Right.

Wilsonian democracy can be boiled down to the following:

- A conceit that “American values” are superior to “Europe’s or anyone else’s values.”

- A vaguely-defined “freedom” is held to be the highest of “American values,” as well as the belief that the application of “freedom” solves all sociopolitical problems.

- The assurance that the United States carries out military-diplomatic endeavors free from any moral compromise or self-interest.

- The belief that prosperity and political stability occur when a people follows the forms of American-style constitutional and parliamentary government (i.e., “tyrants” are bad).

- The idea that “free trade” is an unqualified good.

- The idea that the self-determination of peoples is an unqualified good.

- The claim that American patriotism must include deep loyalty or support for non-American institutions such as the League of Nations or the United Nations.

Enumerating the fundamentals of Wilson’s ideology allows one to see the problems with his idealism. If his points aren’t absurd on their face, such as his ideas about “tyrants” versus “freedom,” or American military-diplomatic endeavors being free of self-interest, then the devil is in the details. What, exactly, are American or European values? And the self-determination of peoples is a concept loaded with dynamite. Is a nation defined by civic ideas, such as what France claims to be, or by blood, such as Germany? Are the two Koreas really a single nation split by different worldviews imposed by other powers? And what about “self-determination” for them? Moreover, is “free trade” really free, or is it merely an agreement on behalf of favored domestic interest groups reached by two governments?

Not only in 1919 but much later as well, such as in the Iraq War, “hard Wilsonianism” did not bring about easy solutions. By the twilight of his presidency, Bush was being denounced as “Woodrow Wilson on steroids, a grotesquely exaggerated and pridefully assertive version of the original.’”[2] [13]

One should make one last, pithy comment [14] regarding Wilson: “People will endure their tyrants for years but they will tear their deliverers to pieces if a millennium is not created immediately.”

[15]

[15]The Soldier as Christ, and the women nurses in the Medical Corps as Mary. The mourning of fallen soldiers is an important community ritual. Diverse societies cannot genuinely mourn [16].

“We cannot make a homogeneous population out of people who do not blend with the Caucasian race. . . . Oriental coolieism will give us another race problem to solve, and surely we have had our lesson.”

—Woodrow Wilson [17]

Not all of Wilson’s ideas were bad, since wide-eyed idealists and visionaries aren’t always lost in the clouds. For example, idealist Jimmy Carter’s investments in military upgrades helped to win the Cold War, and even the Gulf War [18]. Likewise, Oliver Cromwell’s theocratic English Republic passed the very wise Navigation Acts that would eventually make England a superpower. In Wilson’s case, if he had one idea or package of ideas which is still relevant, it should be called “applied white supremacism.”

Wilson carried this out in the following way:

- Enacting immigration restriction – especially from Asia. The quote above comes from when Wilson signed the Immigration Act of 1917 into law, which barred immigration from most of Asia and was nested into earlier immigration restriction acts and other international agreements.

- Ensuing military preparedness in the event of an attack from the non-white world. One researcher tells us, “In 1917, Wilson had spoken privately of the need to ‘keep the white race or part of it strong to meet the yellow race.’”[3] [19] His main effort in this regard was to safeguard against Japan. From the end of the First World War until 1941, American war planners crafted a strategy to defeat Japan which included designing landing craft and organizing shipping schedules, which they were able to put into action immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack.

- Creating literal white supremacy in America’s “Near Abroad.” Woodrow Wilson sent troops to occupy Veracruz, Mexico in 1914, and considered a second occupation later. Wilson sent troops to the border, and even into Mexico itself, in 1916 after the murderous Poncho Villa raid. In 1919, Wilson’s military even fought a skirmish in Juárez. Further afield, he occupied Haiti beginning in 1914, and then Dominica in 1916. These latter occupations stabilized a problematic region and helped to protect America’s interests.

Notes

[1] [20] David Reynolds, The Long Shadow: The Legacies of the Great War in the Twentieth Century (New York-London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2018), p. 40.

[2] [21] Reynolds, The Long Shadow, p. 382.

[3] [22] Reynolds, The Long Shadow, p. 121.