The War Movie

Posted By Morris van de Camp On In North American New Right | Comments DisabledWhile Western expansion in the United States really started when English settlers travelled overland from Massachusetts to Connecticut in 1635, a true film of the Western genre is only set west of the 100th meridian in the years between the Confederate surrender at Appomattox and the coronation of Edward VII. While warfare has existed since time immemorial, a true War Movie is only set between 1933 and 1945, during the time of Hitler and the Second World War.

What makes War Movies different from other movies about war is that they tend to have a sense of moral certainty. This moral certainty is misplaced, but I’ll get to that later. Other movies about war don’t have moral certainty – like Sergeant York (1941), War Horse (2011), All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), The Hurt Locker (2008), and Platoon (1986). Also, these movies are more often about man versus “The System” than anything else. Other movies about war, such as The Rough Riders (1997), venture close to being a Western. Movies about the Napoleonic Wars drift into “romances for the ladies” territory. Along the lines of the conflicts of the early 1800s, War and Peace (1956) is more a story about a spiritual struggle of one man in the context of Napoleon’s conquest of Moscow than anything else.

The War Movies that I think are outstanding include The Longest Day (1962), The Victors [2] (1960), Das Boot (1981), Downfall (2004), Mrs. Miniver (1942), Dunkirk [3] (2017), and Waterloo Bridge (1940). The last movie is an extended flashback to the First World War, but it starts in the Second World War. What I feel make these movies the best of the genre is that the morality is kept in the background of the story, and we see how people behave valorously under pressure, or at least we see what we hope people do under pressure. The Thin Red Line (1998) is a forgotten masterpiece. After serving in the military in various leadership positions, I discovered just how much I sympathized with the Battalion Commander [4] (played by Nick Nolte) in his struggle with an ineffective subordinate upon a second viewing. I didn’t like Nolte’s character on my first viewing.

There are four types of War Movies:

- The brave English and their brave German foe: These films have a sense of nostalgia about them. They often take place during the Battle of the Atlantic, such as The Cruel Sea [5] (1953) and In Which We Serve (1942), as well as Sink the Bismarck! (1960). Movies about the Battle of Britain also fit into this category. These films are like a modernized, fictionalized jousting tournament among the armored, mounted knights of old. The Second World War’s Bolshevik rape gangs are hidden, and the smoldering piles of corpses among the bomb-ruined cities of Central Europe, far from the front lines, are never shown. The tragedy of it all, however, isn’t masked, as in the scene in The Cruel Sea where the captain orders a depth charge attack [5] on a U-Boat submerged under shipwrecked men in the water. The moral dilemma is still there. For example, Sink the Bismarck!’s Fleet Commander, Günther Lutjens (Karel Štěpánek), is played with too much hubris (moral dilemma), but he still has a great pre-battle speech to the crew of his crippled ship (brave German foe):

Meanwhile, let me remind you that our guns have not been damaged. This is still the most powerful ship afloat. I have in my hand a message, addressed to the entire crew. “All Germany is at your side. Your gallantry is an inspiration to our people. You will forever occupy a place of honor in the history of the Third Reich.” This message is signed by the Führer.

These movies are looking backwards; they are Horatio Nelson’s men of iron behaving valiantly in a twentieth-century setting. But these valiant men are serving a doomed empire that bumbled into war.

- The Pacific War: Initially, these movies were cheap propaganda films. Bataan (1943) is a better-made film along those lines. Later, War Movies in the Pacific fleshed out the Japanese characters a great deal more. The best of them is Letters from Iwo Jima (2006).

- The European Theater of Operations: These are usually morality plays with Hitler, the Nazis, and the Germans as a stand-in for the devil. These films can be terribly one-sided. Bomber pilots are brave, but nobody really gives a damn about the Germans who are being bombed. In this view, such civilians are beneath contempt. The Nazis are also depicted as cartoon villains. In War Movies, National Socialist ideals are never seriously studied. All the “cool kids [6]” hate the Nazis, such as in Casablanca (1942). In Enemy at the Gates (2001), the screenwriters awkwardly wedge the “Germans as evil” element into the story of the Battle of Stalingrad so badly that it appears as an afterthought in what would otherwise be a stellar film.

- The Holocaust Flick: There are many Holocaust movies. Of these, I have only watched one, and we’ll get to that later. The morality of these films is spread on the audience with a trowel.

Spielberg’s War Movies

The most important maker of War Movies today is Steven Spielberg. While there are a great many War Movies that are in some way better than Spielberg’s, his are the most important because the moralizing is so efficiently packaged. Additionally, the Jewish metapolitical agenda is so artfully done that one doesn’t see the brainwashing while it is going on. Spielberg’s War Movies include the following:

1941 (1979)

Empire of the Sun (1987)

Schindler’s List (1993)

Saving Private Ryan (1998)

Then there are the action-adventure films featuring Nazis, Arabs, and the Vichy French as cartoonish, anti-Semitic villains who exist solely to be chopped up, melted by supernatural forces, shot, or dispatched by some other spectacular form of death. They are:

Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989)

On a scale from 1 to 10, with 10 being the highest, Empire of the Sun rates somewhere around a 4, and there is nothing more to say about it. The next most important of Spielberg’s War Movies is 1941. There is a bit of the Jewish view of the war here. It is an irreverent comedy along the lines of Animal House (1978). Both movies star John Belushi. In this movie, the Japanese threat is downplayed. Resisters of racial integration are mocked, and the Zoot Suit Riots [7] are portrayed in a comedic light rather than the foreshadowing of the disastrous 1965 Immigration Act that they were. This is comedy that supports Jewish aims, both during the war and after. Jews don’t care about any enemy of America other than enemies of the Jews. During the Second World War, Germany and Italy were not a threat to the United States in the same way Japan was, but they were a threat to Global Jewry. Jews also support racial integration and non-white immigration while ignoring or downplaying the costs (i.e., the Zoot Suit Riots).

[8]

[8]New York Times cartoon from November 1, 2018: The organized Jewish community only cares about Jewish Enemies, not American enemies. American troops “enroll [sic] to fight in the Middle East” rather than defend the Mexican border from an illegal immigrant caravan.

Schindler’s List is the definitive War Movie of the Holocaust genre. And it’s the only Holocaust movie I’ve watched. The plot is as follows:

- Jews are moved to the Krakow ghetto. The main characters are introduced.

- Oscar Schindler (Liam Neeson) gets Jews in the ghetto to invest in his operation. This is a subtle dig against Gentiles. Schindler must get investment capital from Jews to get an idle factory running instead of Polish or German investors.

- The SS moves in, builds a concentration camp for essential workers, and then liquidates the ghetto at Krakow.

- Schindler’s factory becomes a haven for the Jews.

- The movie’s climax occurs when a train carrying Jewish women and children is accidentally sent to Auschwitz, and Schindler saves them.

- The Soviets arrive and free the Jews. Schindler is declared “righteous among the nations.”

Schindler’s List is interesting in that one sees how Jewish cultural holidays such as Passover and Purim developed. These holidays are not about a message from a particular god or some other spiritual matter; instead, they commemorate Jewish-Gentile conflicts. The religious aspect of the Holocaust is evident even in the opening scene. Spielberg shows a modern-day Jewish ritual in color, and then there is a jump cut to Jews being put into the Krakow ghetto in black-and-white. Schindler’s List is thus the Book of Esther and the flight from Egypt in Exodus, repackaged in 1940s Eastern Europe. It is a work of religious mythology, not history.

There are some unpleasant details that must be discussed here, namely the religious aspects of Schindler’s List and the Holocaust, rather than the historical truths of the matter. Technology has changed since 1993, when Schindler’s List was released, and now one can watch actual mass killings[1] [9] filmed by ISIS, Chechens, or others from the comfort of one’s couch using a smartphone. In light of that new, horrible reality, when I watched Schindler’s List I couldn’t help but see it as a semi-pornographic scary story meant to scare naughty Jewish children.

The scene depicting the night of the ghetto’s liquidation conveys the biggest sense of this. In it, after the buildings have been cleared of those who leave cooperatively, German soldiers with stethoscopes listen through the walls of the buildings to locate hidden Jews. There is even a Jew shown hiding under a bed, like a cartoon character. There are Jews in fake wardrobes and hidden chambers – but they are all killed while classical German piano music plays in the background. The “”swallowed diamond” story [10] and the “kid hidden in the latrine” story are both presented in other parts of the movie. Eat your veggies, kids, or the goyim will shoot you!

There is another ugly detail that needs to be discussed. The ISIS snuff films demonstrate the key problem in mass killings: disposing of the bodies. ISIS carries out their mass executions after herding their marks into an already-dug mass grave, or else they shoot their victims on a riverbank and dump the bodies into the water.

In Schindler’s List, body removal is avoided altogether. The logistics of removing lots of bodies from apartments – taking them down the stairs, into the street, and finally carrying them to a mass grave – is not shown, except for one scene, where we see the decomposed corpses being piled and burned in an open funeral pyre. The implausibility of muddy half-skeletons burning in such a way makes this reviewer think that the purpose of the scene is to explain why there isn’t a mass grave of Jews who were killed in Krakow in 1943 to be found (although this isn’t to imply Jews in Krakow in 1943 weren’t treated unjustly in many circumstances at the time).

And finally, Schindler’s List isn’t an examination of why the Holocaust happened. Indeed, none of the mainstream “lessons of the Holocaust” films ever really impart any wisdom regarding this. An example is how the screenwriters wrote the speech [11] that Hauptsturmführer Amon Göth’s (Ralph Fiennes) delivers to his men just before they liquidate Krakow’s Jews:

Today is history. Today will be remembered. Years from now, the young will ask with wonder about this day. Today is history, and you are part of it. Six hundred years ago, when elsewhere they were footing the blame for the Black Death, Casimir the Great, so-called, told the Jews they could come to Krakow. They came. They trundled their belongings into the city. They settled. They took hold. They prospered in business, science, education, the arts. They came with nothing. And they flourished. For six centuries there has been a Jewish Krakow. By this evening, those six centuries will be a rumor. They never happened. Today is history.

If Jews had made such great achievements in business, science, art, and so on, why shoot them? Schindler’s List is fundamentally a blank on that count. As with all War Movies, the moralizing narrative begins with the Nazis already in power and the Jews and their other adversaries on the run. There is no discussion of the Jewish-led Communist revolutions that took place across Europe after the First World War, nor the Bolshevik attack on Poland between 1919 and 1921. There is nothing about the mistreatment of Germans in Eastern Europe after the war, the German hyperinflation that was created in part by Jews in the Weimar Republic’s Treasury Department, or any other factor that made the Nazis a viable option for German voters. There is also no discussion of the tremendous tensions between Poles and Jews. When Poland was part of the Russian Empire, it was given over by the Czars to a Jewish mercantile class who exploited[2] [12] the population.

[13]

[13]Spielberg’s imagery is highly anti-goyim. Above, we see what could be a German, Polish, or even Iowan farm boy in a uniform looking dully at a Jew. Suddenly, he pulls out a pistol and shoots him. Below are two blond goyim, one probably Polish and one German, screaming madly with hate.

Saving Private Ryan

Spielberg’s most important War Movie, however, is Saving Private Ryan. When the movie first came out, it was highly praised by critics and viewers alike. It is considered to be realistic, gritty, and patriotic. Much of the feel of the film is influenced by the work of the 1990s pop-historian, Stephen E. Ambrose, who was then at the height of his career and fame. Throughout that decade, Ambrose published a number of bestselling books, including D-Day, Band of Brothers, and Citizen Soldiers.[3] [14] These books portrayed the Americans as something like plastic demigods who were fighting for a righteous cause. Ambrose was the film’s historical advisor.

Due to Saving Private Ryan’s supposed realism, this writer heard stories of Second World War veterans (many of whom were still living in 1998) walking out of the theater, weeping or something like that, during the vicious opening scene depicting Omaha Beach. I even recall the story of a convicted vandal who had desecrated a veteran’s monument somewhere in Middle America who was forced to watch this movie as part of his sentence.

Since so many people have already remarked upon this film, some of what I write will be a repackaging of other’s ideas intermixed with my own. Some of these ideas came from the old Alternative Right Website that Colin Liddell and Andy Nowicki edited before it was bonfired by Richard Spencer in 2013, although I can’t remember precisely which articles, and they don’t seem to be online anymore.

The plot is as follows:

- Muh Omaha Beach Scene.

- The Chief of Staff of the Army orders that Ryan should be taken off the front after he discovers that Ryan’s brothers have all been killed in action.

- Captain Miller assembles his squad to save Private Ryan.

- Captain Miller’s squad attacks a machine-gun nest. The Americans take a German as a POW, but release him. This event sets up other plot elements.

- Captain Miller’s squad finds Private Ryan. Ryan refuses to be taken off the front line, setting up the final battle.

- During the final battle, most of the members of the squad are killed; Captain Miller is killed by the POW he had ordered released.

- The main force of the American Army arrives from Normandy Beach in the nick of time, and Private Ryan is finally saved.

[15]

[15]Prisoners killed in the Muh Omaha Beach scene: Saving Private Ryan conveys the same metapolitical – “kill a Nazi” – concept as in The Blues Brothers, except with better cinematography and special effects.

There is a great deal of military fakery in this film. For example, orders to “save” Private Ryan of the 101st Airborne Division wouldn’t be carried out in the way it is shown here. The orders would have gone from the Chief of Staff, through the chain of command, and down to Private Ryan’s direct commanding officer. This wouldn’t have been a major technical challenge, since Airborne divisions jump along with their artillery, clerks, quartermasters, lawyers, radiomen, doctors, and headquarters staff, and these units are expected to send and receive important messages from Headquarters – but ignoring this fact allows the story and its message to be expressed better.

Saving Private Ryan is a glorification of war, not its opposite, as one supposes. For further reading on that regard, I suggest this Counter-Currents article [17]. Some of that article’s ideas are remarkably similar to YouTube reviews of the film, here [18] and here [19]. They go a bit further than the article in that they point out something which one really doesn’t see upon a first viewing – namely, that Saving Private Ryan encourages war crimes. This refers to scenes depicting the beating or torturing of unarmed prisoners of war, as well as shooting enemy soldiers after they have already clearly surrendered.[4] [20]

The movie also demonizes and dehumanizes the German soldiers through several filmmaking tricks. Germans get shot down like targets at a shooting range, and are not shown to feel or express pain. Their deaths are shown at a distance, or through smoke and haze. The Germans run like rats in a trench, surrender quickly, and cower in fear. When seen up close, they are depicted as hard-faced, older men. In this regard, this film is propaganda – skilled propaganda, but just as crude as any poster showing a gorilla wearing a Pickelhaube [21].

Captain Miller’s Squad

Part of what makes the War Movie unique in relation to other movies about war is a consequence of the training, doctrine, and technology of the time they are depicting. In the case of films set during the Second World War, this change in training and technology meant that a squad could operate independently, equipped with a radio and various types of weapons. As a result, the infantry squad has come to be the perfect element to focus on for a good story. The wide range of equipment and skills that were present in a typical Second World War-era squad allow for a variety of combinations in teamwork, tools, and skills to be shown. A squad is also small enough that the audience can remember who the different characters are, yet big enough to include a wide range of personalities.

In a movie set during the Civil War, all the soldiers in an infantry squad of that time would have been carrying the exact same weaponry and all had the same role in battle: stand, shoot, reload, shoot . . . and so on. Therefore the action in those types of movies usually centers on the characters in the Regimental Field and Staff Company, i.e. the Colonel, the Sergeant Major, the Adjutant, and so on. Likewise, in a medieval European setting, a war story is typically centered on a knight and his squire, pages, and so forth – not on the ranks of longbow-men.

Thus, in Saving Private Ryan, we have a squad – but it’s really more of what is nowadays called a Special Forces A-Team. An A-Team is commanded by a Captain, and his soldiers are higher-ranking noncommissioned officers (NCOs). An infantry squad is commanded by a Staff Sergeant or a Sergeant. The Saving Private Ryan squad’s NCO-in-Charge is a Sergeant First Class; a person more senior would otherwise be in an infantry squad, but is the right rank for an A-Team. There is also a translator and a medic, which are skilled positions in an A-Team, but not in a regular infantry squad. Combining the attributes of an A-Team with a regular Second World War-era infantry squad allows the storyteller a broader latitude to get the message out.

The Saving Private Ryan squad in detail, from a critical perspective, is as follows:

Captain Miller (Tom Hanks): Being named “Miller” is important, as it could be of WASP or German origin, or some combination of the two. He is also a Pennsylvanian, a place where WASPs and Germans are highly intermixed. This is also the part of the United States which is the most ideologically moderate. Captain Miller thus represents Middle America.

Sergeant First Class Horvath (Tom Sizemore): He serves as the NCO to provide realism. His death ups the emotional intensity

Private Jackson (Barry Pepper): Jackson is a Bible-verse quoting Appalachian. He is not ideological and believes in the mission. His death also ups the emotional intensity.

Private Caparzo (Vin Diesel): He represents unnecessary sentimentality, and his death ups the intensity.

Tech 4 Wade (Giovanni Ribisi): As a medic, his presence allows the viewers to see the horribly wounded on Omaha Beach. Although he is unarmed due to his role, Wade strangely takes a forward role in the attack on the machine-gun nest. His agonizing death anesthetizes the audience to the fact that, afterwards, the squad tortures a prisoner of war and denies him water, even though he is doing hard work, and nearly kill him in cold blood.

Private Reiben (Edward Burns): He is from Brooklyn, New York, and is possibly Jewish. He believes in the mission and is very eager to kill the German POW.

Tech 5 Upham (Jeremy Davies): Upham wears the patch of the 29th Infantry Division – a unit that, both then and now, is part of the Virginia National Guard. However, the Upham name in America originates among the Yankee Puritans of New England. One of Wisconsin’s early political leaders was Don Alonzo Upham, born in Vermont. While Tec 5 Upham is not an infantryman, he was on Omaha Beach, as evinced by his captured German helmet. He is upper class, skilled, and knows several languages.

Private Mellish (Adam Goldberg): He is a Jew and is open about it. His death is a metapolitical message to ethnonationalist Jews, and is in fact the metapolitical point of the movie.

The Death of Private Mellish

Saving Private Ryan is unique in that the big battle takes place at the beginning of the film, but there is also something else different about it: the climax of Saving Private Ryan is shifted. One would think the climax would come when Captain Miller’s squad meets Private Ryan and saves him, but instead, the squad meets Ryan during a point in the story where the tension is still rising. As a result, the plot demands one more big battle. In this fight, the two key characters – from a Jewish metapolitical perspective – move to center stage.

In the lead-up to the final battle, Captain Miller positions Private Mellish and Corporal Henderson (Maximilian Martini) in a house with a machine gun. Tech 5 Upham’s job is to run ammunition to the various defensive positions. As the battle rages and the movie draws toward its climax, Private Mellish ends up alone, out of ammunition, and in a fight to the death [22] with a hard-faced soldier of the Waffen-SS. At first Mellish cries out for Upham, but as the fight becomes more intense, he cries out for help to Private Reiben – the soldier who could be Jewish. Meanwhile, Upham is unable to find the courage to climb the stairs and save Mellish. When the knife fight ends with Mellish dead, Upham and the SS soldier look at each other in the stairwell, shrug, and then each go their own way.

Since Saving Private Ryan is fiction, Spielberg could have had the scene play out in any number of ways, but he chose the one that has the biggest Jewish ethnonationalist impact. Upham, the upper-class Yankee who knows several different languages and comes from highly skilled white-collar jobs, doesn’t save the Jewish Mellish, although it would have been very easy for him to do so. Additionally, although he is a clumsy guy, Upham has been as brave a soldier as any – landing on Omaha Beach, traveling with the squad, and running ammo under fire. His courage only fails him when he has to save a Jew. Furthermore, when he captures the Germans at the end of the battle, Upham only shoots the one whom he had saved from summary execution, while the other Germans are let go. Upham thus represents America’s political and social elite that are of Yankee extraction. They will shoot an enemy who personally betrayed them, but aren’t interested in “saving Jews.” It thus reflects the fact that the biggest ethnic conflict in North America is that of Yankees versus Jews.

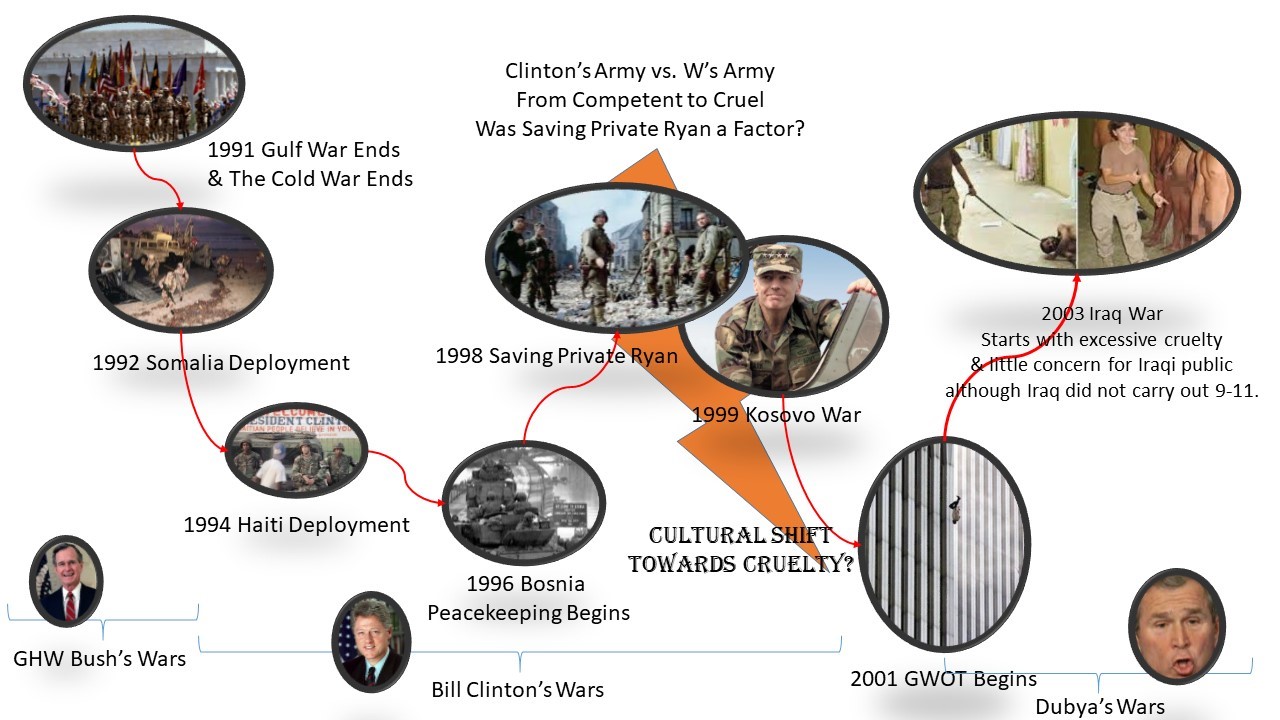

A Green Light for Cruelty in Iraq?

Saving Private Ryan came out within the span of the average single enlistment of an American soldier who served in Afghanistan or Iraq, specifically from the time of the film’s release until 9/11 and the ensuing wars. Thus, young men who were in the service during the invasion of Iraq had surely all seen the film and attempted to imbibe the “lessons” from it. One officer in the military at the time remarked to this writer that the ethical issues surrounding Captain Miller’s attack on the machine-gun nest were often discussed; however, they were only discussed in part. The question was if Miller gave the correct order to attack the nest in the first place. Is it one’s duty in war to accomplish one’s narrow mission, or to do additional things to try to help the end the war more quickly? The treatment of the prisoner at the machine-gun nest, or the more generalized shooting of unarmed Germans throughout the film, was not discussed, however.

[23]

[23]From competent to cruel? Did Saving Private Ryan contribute to a culture of cruelty in America’s armed forces prior to the Iraq War?

It might be possible that the scandals and cruelty practiced by the US military in the opening months of the Iraq War were partially the result of the messages soldiers received from Saving Private Ryan. Consider this: Between 1991 and 1998, the United States deployed troops to a great many places. In those places, American troops behaved well within the bounds of traditional Christian chivalry. The Kosovo War occurred after Saving Private Ryan’s release, but it mostly played out through an air campaign and international diplomacy – not direct action by ground forces. On the other hand, the Iraq War took place after events that paralleled the opening of the Second World War: There was a “sneak attack” like Pearl Harbor, and Saddam Hussein (at least how he was depicted in the media) was a great stand-in for Hitler.

Americans in Iraq were far crueler towards the Iraqis than they were towards the Haitians or Bosnians. I personally knew men who served in Haiti – all of them had dealt with rioting Haitians at some point, but handled the situations calmly. In Iraq, the atmosphere was much tenser, and there were several critical months between March and August 2003 when Iraq could have been as calm a deployment as Bosnia, had the Americans bothered to keep the electricity running in Baghdad during that time. Instead, the Jewish-centered, hate-filled narrative of Saving Private Ryan, as well as those of hundreds of other War Movies, allowed the Iraqis that American soldiers encountered – who were often civilians with no particular ideology who posed no threat to them – to stand in for the “Nazis.” As a result, the lives of many Iraqis and Americans came to an untimely end because of the mythology the Americans had imbibed from the War Movie genre. Ultimately, War Movies are highly entertaining, but be mindful of the message you might subconsciously receive from them.

Notes

[1] [24] It is well known that mass killers are not always ashamed of their killings; often, quite the reverse. ISIS’ killings are legendary, but Czech partisans and their Bolshevik allies also filmed mass killings of Germans at the end of the Second World War. In this film [25], we see the mass murder of Germans in Prague. After they are shot, a truck drives over their legs. This leads me to think, why didn’t the Nazis make films of Jews being gassed in the showers at Auschwitz? If ISIS and Edvard Beneš’ government filmed their mass murders, why didn’t the Nazis do so also?

[2] [26] In his book Jewish Supremacism, David Duke writes: “Jewish historian Edward Bristow writes about the world prostitution network and clearly shows the prominent Jewish role. It is not hard to conceive of the reaction of many Eastern Europeans to the Jewish enslavement and degradation of tens and thousands of Christian girls. Bristow reveals that the center of the Jewish trade in Gentile women from Poland and surrounding regions was a small town called Oswiecim, which the Germans called Auschwitz. That simple revelation can bring much understanding of the recurrent Jewish and Gentile Conflict” (pp. 190-191).

[3] [27] Of the three, Citizen Soldiers is the best.

[4] [28] Ambrose mentions that the shooting of POWs really did occur, although he mentions repeatedly that the Americans liked the Germans more than any other people who they met during the war.