Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald is the latest installment in the ever-expanding Wizarding World franchise and the second film of the Fantastic Beasts series. Much like Peter Jackson’s bloated Hobbit trilogy, the Fantastic Beasts franchise is an unapologetic cash grab and will sprawl across five films, approaching the length of the original Harry Potter series.

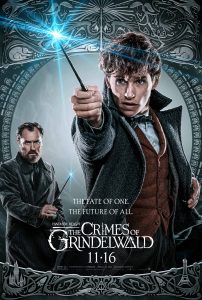

The series was originally meant to follow the adventures of the eccentric magizoologist Newt Scamander, under whose name J. K. Rowling published a slim textbook on magical creatures entitled Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them (the name of the first Fantastic Beasts film).

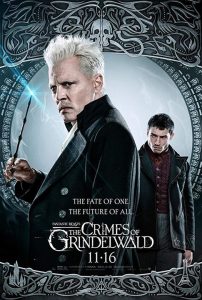

But Newt has taken a backseat, and the trajectory of the series has ended up morphing into a thinly-veiled allegory of the rise of Hitler. Rowling spends too much time on Twitter. The figure looming over the franchise is now Gellert Grindelwald (Johnny Depp), a powerful German wizard who wants to establish the supremacy of pure-blood wizards over Muggles.

Grindelwald’s backstory is introduced in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. At 16, he was expelled from Durmstrang (a wizarding school somewhere in Northern Europe) for conducting experiments in the Dark Arts. He then went to Godric’s Hollow in search of the Deathly Hallows, where he met Dumbledore. They became close friends and made plans to find the Deathly Hallows together and start a revolution in the name of wizard domination.

Dumbledore severed ties with Grindelwald after his sister was killed in a three-way duel between the two boys and Dumbledore’s brother Aberforth. Grindelwald went on to enact his plans for wizard domination and thereby ignited the global wizarding war, a conflict that lasted until Dumbledore famously defeated Grindelwald in a duel in 1945.

Grindelwald is obviously meant to be a Hitlerian figure, and viewers are repeatedly whacked over the head with allusions to Hitler and National Socialism. Grindelwald’s emblem is an eagle, his residence at Nurmengard resembles Berchtesgaden, and his speech to his followers has the aura of an NSDAP rally.

Grindelwald is obviously meant to be a Hitlerian figure, and viewers are repeatedly whacked over the head with allusions to Hitler and National Socialism. Grindelwald’s emblem is an eagle, his residence at Nurmengard resembles Berchtesgaden, and his speech to his followers has the aura of an NSDAP rally.

If only Depp had taken on some of Hitler’s charisma and energy as well. His performance is dull and underwhelming, like the film itself.

The film takes place in the year 1927. Grindelwald escapes custody and flees to Paris in search of a boy named Credence Barebone, who he thinks will be able to aid him in killing Dumbledore, now his greatest foe. Credence is also sought after by Newt and co., who know that Grindelwald wishes to recruit him to his cause. Most of the film is a race to see which side can win him over first.

Credence’s origins are the subject of much speculation because he was adopted by a Muggle (or “No-Maj”) woman as an infant. It is shown in the first film that his mother was an ardent anti-witchcraft activist who abused him and stifled his magical abilities. This led him to develop an Obscurus, a parasite that contains its host’s repressed energy and can erupt violently under the right circumstances. Credence’s Obscurus wreaks havoc upon New York in the first film.

Ironically, Credence’s story undermines the film’s pro-Muggle/anti-racist message: he would have had a much less traumatic upbringing had he been raised by other wizards. His life demonstrates the harmful effects of being raised by a single mother of another race (so to speak) and the psychological necessity of belonging to community of people like oneself. His real-world counterpart would be a white boy raised by a black female social justice activist with a grudge against white people. It follows from Credence’s story that such a child would be much better off being raised by white parents.

This is far from the only example of how Rowling’s Leftist proselytizing stands at odds with the Harry Potter universe and the conventions of fantasy literature she employs. Hogwarts is an elitist institution modeled on English boarding schools (architecturally modeled on Gothic and Norman cathedrals/castles) and is associated with centuries-old traditions, ancient lore, and esoteric spells and initiation rites. Despite the fuss over racism, the Harry Potter mythos is implicitly white, and most of its fans are white.

Toward the end of the film, Grindelwald summons his followers to a rally at the Lestrange family crypt and delivers a speech. His rhetoric is actually rather mild. He frames himself as a champion of world peace: breathing into a skull (engraved with his motto, “Für das Größere Wohl,” in Fraktur lettering), he foretells the future and conjures images of nuclear war as proof of Muggles’ hubris and why wizards should rule over them.

Grindelwald claims not to hate Muggles and states that they are “not lesser, but other.” He also claims to fight for “freedom, truth, and love.”

This is a clear attempt by Hollywood to link the reasonable, common-sense principles of white nationalism with a caricatured image of National Socialism. Some years ago, Grindelwald might have been portrayed as a violent lunatic who openly declared his genocidal intentions. But Hollywood can no longer ignore the emerging force of “white nationalism 2.0,” so they are left with the option of discrediting it by tethering it to Hitler. The enemy fears nothing more than the prospect of white nationalism breaking free of its twentieth-century baggage and gaining ground among ordinary people.

This fear is indirectly voiced at the beginning of the film when the British Ministry of Magic agrees to annul Newt’s travel ban under the condition that he help locate Credence (Newt turns down the offer, but Dumbledore later convinces him to take on the mission). They warn Newt that Grindelwald is growing in power and that his ideas are “seductive to some members of the community.”

Credence is forced to pick sides at the end of the rally when Grindelwald casts a circle of blue fire around him and invites his followers to step inside. Credence joins him, knowing that he holds the key to his identity. The intelligent viewer will question whether this is really a bad thing in light of the fact that gaining a sense of belonging can have a healing effect for Obscurials, whose condition arises from being tormented by Muggles and being cut off from fellow wizards (another example of tension between wizarding lore and the political message tacked onto it).

In addition to its dreary Left-wing moralizing, the film’s main flaw is its plodding, clunky rhythm, the result of the clutter of side-plots, background information, superfluous supporting characters, etc. It is sluggish and dull. The main arc of the story could have easily been condensed into a 20-minute segment.

The main diversion surrounds a false lead regarding Credence’s origins. He is initially thought to be Corvus Lestrange V, scion of the pure-blood Lestrange family and the last of his line. Corvus was the favored child of his father, who had previously born a daughter (Leta Lestrange) by a Senegalese woman whom he had kidnapped. The woman’s other child, Yusuf Kama, swore to avenge his mother’s kidnapping by killing Corvus. He followed Credence to Paris, thinking he was Corvus. But it is later revealed that Leta Lestrange swapped Corvus with another baby on the voyage to America; the ship was evacuated, and the lifeboat with the real Corvus sank.

At the very end of the film, we learn that Credence is actually Aurelius Dumbledore, Albus Dumbledore’s long-lost brother (more likely half-brother, since he is 18, and Kendra Dumbledore died about 30 years before the film takes place). The increasing banality of the Wizarding World franchise would seem to demand proportionately baffling plot twists in order to sustain viewers’ interest.

The main takeaway from this forgettable film is that the establishment is deeply afraid right now. Expect legions of middle-aged pussyhat-wearing women to take to social media comparing Trump to Grindelwald as they literally shake in terror.

Fantastic%20Beasts%3A%20The%20Crimes%20of%20Grindelwald

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

Pour Dieu et le Roi!

-

Counter-Currents Radio Podcast No. 582: When Did You First Notice the Problems of Multiculturalism?

-

Civil War

-

Why the Left Doesn’t Understand Optics

-

Psychoanalyzing the Natives: The Big Lift

-

Made in Britain: The Rise and Fall of Skinheads

-

Confronting the Root of Race Denialism

-

Dune: Part Two

6 comments

Rowling is a moderately talented writer of books for children that seems desperate to be taken seriously as an author. The revisionist virtue signaling that has followed the end of the book series (Hermione is a black, Dembledore is homosexual) smacks of someone who became wildly famous and desires to have the feeling of being in the spotlight back while gaining the approval of her more serious peers. Trying to cram contemporary issues into a world that was written decades ago never goes well (e.g. George R.R. Martin trying to turn GoT into a morality story about “climate change”) and this sounds like more of the same.

I have always thought that Johnny Depp would was the logical choice to play the Joker after Heath Ledger died. I think he would be great at it.

I cannot understand the appeal of J.K. Rowling’s pedestrian prose and derivative storytelling.

Ursula Le Guin had a ‘school for wizards, and went far beyond in her first Earthsea trilogy — and that was back in the 70s! Now Le Guin was an avowed anarchist feminist (surely a polity doomed to instant capitulation), but in her earlier fiction she eschewed sermonising in favour of buiding her taoist and jungian tinted mythos in grave spare prose.

In contrast, Rowling, since acquiring fame and riches, has never let up nagging and scolding us: she is a regularly consulted oracle on British television, and this latest cinematic effort, complete with blond teutonic antagonist, seems just more of the same.

Right off the bat, I could never get used to her naming conventions (for pretty much everything). I guess that it could be justified in the case of early HP books, by saying that they were very much whimsical British fable for kids, but it just added to ridiculousness once she began to transform them into Real Serious Business Fantasy.

There were so many plot holes and such in the first movie that I’d never see another Fantastic Beasts movie again.

I always thought Harry Potter series was kind of shitty because the message was so basic bitch. Basically bigotry and racism are bad. The bad wizards hated muggle born wizards and muggles because of childhood abuse, or just because reasons. It’s the same message I have been fed since I was in kindergarten.

Harry Potter would be so much better with a bit of nuance. For example JKR could have shown that pure bloods really did have stronger magic on average so that the Malfoy’s and other pure blood families’ worldview would make a bit of sense.

The best propaganda is subtle. On that criterion I would say Harry Potter is bad propaganda. But on the other hand a lot of people love it so what do I know?

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.

Paywall Access

Lost your password?Edit your comment