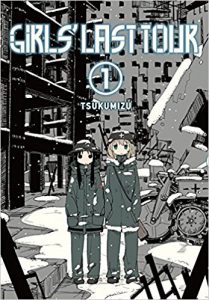

Girls’ Last Tour (2017)

Directed by Takaharu Ozaki

Written by Tsukumizu

Girls’ Last Tour is a short (twelve episodes, manga-based) slice of life/adventure anime. Unlike the cutesy and safe setting of contemporary Japan common to the genre, Girls’ Last Tour is a post-apocalyptic journey through an industrial wasteland. Chito and Yuuri, both fourteen, are continually escaping from one predicament to another, with Chi driving their (ridiculous) Kettenkrad half-track motorcycle while Yuu normally sleeps in the back. They contrast against and adore each other, bound together by circumstance; Chi is the bookworm, faithful journal keeper, and practical-minded driver, continually playing off against the absent-minded, ditzy, and seemingly fatalistic Yuu, who forever lives in the moment. The show is a series of vignettes of their experiences, delivering existential meditations on war and survival. It is intensely contemplative without being boring, quirky without being silly, and adult without being unsuitable for children.

Like all quality shows, the opening episode perfectly summarizes the dynamic at play and the characters’ purpose (within barely a minute or so, actually). Chi and Yuu (or rather, just Chi) are trying to escape an underground labyrinth, and make twist after turn in a desperate search for daylight. Chi comments, “Whose idea was it to come down here in the first place, anyway?” and Yuu replies, “I don’t know. I think it was you, Chi?” She is flatly told, with no hesitation, “It was you.” It’s hard to convey comedic timing in writing, so enjoy watching it for yourself; the snappy punchline breaks the tension built through long establishing shots. It’s so extremely deadpan that one wonders if the humor is even intentional. Yuu later comments that she would burn someone’s most treasured possessions to see if they would really kill themselves, and Chi comments, “What are you, the devil?” Yuu can only laugh and enjoy the moment.

They inhabit a multi-tiered, sprawling metropolis, which has been completely ruined and is otherwise nondescript. Endless grids of uninhabited buildings stretch to the horizon and beyond. War, famine, and plague have seemingly snatched away all other signs of life, apart from a few survivors whose presence is as mysterious as Chi and Yuu’s own. The first person they encounter initially struggles to remember how to speak. When they bed down for a night in an unlocked residential block, the room is nearly devoid of furniture, showing little sign that it was ever inhabited at all. There are tell-tale indications that, even before the war, the civilization was in terminal decline: a makeshift elevator is attached to the column going from one level to the next, because the previous inhabitants had had no idea how to operate the main elevator inside. Yuu comments that, at the top of the building, there might be “a group of happy people doing fine,” sounding incredibly bored by the prospect. Both of them are traumatized by a genocidal conflict that is seen only in their recurring nightmares – the last glimpse of their grandfather, who lent them the half-track.

Having the girls walk a knife edge of survival through an unexplained world amplifies the tension between the “straight man” and the “clown” in their Boke and Tsukkomi routine, and the threat of death elevates the show’s moments of humor from being mere comedy to becoming part of a discussion on the meaning of survival. Food and fuel are scarce, and the journey is a game of choice and chance. Their fortunes alternately vindicate Chi or Yuu’s sensibilities. In one early episode, it’s Chi’s knowledge, intuition, and experience that leads them to find a fish to eat in an outflow of melted snow (Yuu bizarrely comments that the fishbones “must feel refreshed after having all the meat picked off them”). In another, their Kettenkrad has broken down, and Chi is deep in concentration trying to fix it and thereby save them from death by exposure. The dialogue alternates between them, with Chi despairingly saying, “It’s no use” and “It’s hopeless.” Yuu lounges around, chewing on a piece of metal, exclaiming how beautiful and peaceful the weather is. They are saved by a fluke encounter, and they repay the visitor in meticulous hard work – only for fate to snatch away all prospects of escape from the dying city. Yuu is blissfully indifferent, making up a cheerful nonsense song: “Hopeless, hopeless, hopeless. Hopeless is hopeless, and hopeless is . . .”

But when Yuu is forced into existential fear and contemplation by being plunged into pitch darkness, she frets about what she would do if she lost Chi. It’s a revealing moment that shows how indispensable the Tsukkomi is to the Boke; a clown alone can be impressively skilled, but needs a partner to make the unexpected meaningful. Yuu’s progress depends on the practical-minded Chi, who literally ferries her around, yet Chi depends on Yuu’s physical fearlessness for survival and dear company. Dignity and dependability are played off with exuberance, light-heartedness, and unorthodoxy. The same situation is later played back in reverse: Chi is reduced to desperation by the prospect of the crushing loneliness of losing Yuu, which brings out a more resolute determination and self-realization.

It’s to Girls’ Last Tour’s credit that such a simple trope is retold in a compelling way that makes use of the contrast between the characters to riff on such a wide range of subjects. One of Chi’s treasures is a copy of Kappa by Akutagawa, a famous Gulliver’s Travel’s-like satire on the corruption within the Japanese social hierarchy that was published in 1927 (in Girls’ Last Tour, the city is literally hierarchical, and follows their ascent). The illiterate Yuu is at ease when she burns the book for fuel, but is eaten up with regret when she realizes how badly she has betrayed her partner’s trust. But she is not above betraying that trust for a prank – in the opening episode, Yuu points a loaded rifle at Chi and demands the last of the five biscuits in a ration pack.

Would she really kill her partner for a biscuit? After all, as she says, “This is war.” At this point, neither Chi nor the viewer knows, and the tension is so thick you could cut it with a bayonet. The relief comes when she “really eats it” and points her gun away, at which point Chi tackles and beats her, upset. But to Yuu, it doesn’t matter, and she just carries on laughing, since her unorthodoxy allowed her to get the edge. With no standard of normality to refer to, and no society to condone or condemn their actions, it’s up to the viewer to decide which of the pair’s outlook is more valid. In the case of the burnt book and the meaning of memories, Yuu utters the brilliant aphorism that “memories just get in the way of living,” a statement which is deliciously cynical and yet subtle in its context. The continual brilliance of the writing, creative direction, and narrow focus of the show highlights how lacking and lost Western media is by contrast, given that it is unable to have a serious discussion about anything.

Yuu’s adventurousness enables them to venture further and accomplish more than Chi ever could alone, and her lightheartedness is soothing in moments of grief. She comments that “you don’t need a reason [to carry on living] . . . There are nice things sometimes.” Chi, ever conscious of the risks and the fact that their survival at stake, is terrified of heights, and, being more introverted, lives with a sort of practical melancholy. Yuu recharges with relaxation, while Chi strives for certainty and permanence. It’s not a coincidence that Yuu is the more iconographic of the two protagonists – both of them are minimally-drawn avatars for the viewer’s self-insertion, but Yuu is even more so (her eyes are simply colored ovals). She is the more feminine and physically well-developed of the two, with Chi seeming androgynous or boyish next to her full figure and flowing blonde hair. It plays on the same motif that Miss Kobayashi’s Dragon Maid rode as far as the flying reptile would go, with one viewer inferring that the show was about “chaotic, feminine-coded forces of nature brought to heel by easily self-insertable men women.”

Only by placing Chi and Yuu’s double act in an empty world and focusing the attention on them alone can they expand into wholly believable and endearing characters, resulting in a more captivating story. The show has an insistent focus on transient beauty and features Zen-like moments that provide respite from the ever-present reminders of desolation. It continually questions impersonal, abstract, and theological arguments for wars of “salvation”; being orphans of a war of total annihilation, Chi and Yuu lack the basic knowledge of everything from cheese, the ocean, radios, videos, cameras, chocolate, houses, and the Earth’s rotation. Their surroundings echo Vonnegut’s assertion that the barren remains of firebombed Dresden were like “the surface of the moon.” And yet the show never lapses into explicit moralizing. Yuu is especially disappointed that she can’t eat the fake fish in a temple mock-up of “paradise” – to her, the gods on offer are “a big disappointment.”

Their journey is an emotional seesaw between hope and serenity amidst the stifling claustrophobia of the dead and crumbling city. The anachronisms of the girls’ outfits and equipment only adds to the historical confusion. The Kettenkrad, Yuu’s rifle, and their helmets are all from the era of the Second World War, and yet they encounter advanced robotic weapons that can obliterate a city, and at one point rummage for supplies in a nuclear submarine. It all adds to the sense that all the world’s wars have been piled on top of one another and have finally rolled into one ungodly, all-consuming cataclysm.

Towards the end of the series, the show goes in somewhat bizarre and unexpected directions. New creatures are introduced – robot, rodent, and seemingly extraterrestrial, while out-of-place commentary about machine evolution and the Earth going into lifeless slumber is heard. Nonetheless, the essentials of the show aren’t abandoned. Chi is shown sleeping on a book that she’s using as a pillow, but which she can’t read (War and Human Civilization, likely a meant to be Azar Gat’s War in Human Civilization), and later, Yuu nearly meets her doom by being insufficiently cautious. The fear of the unknown lurking in the cramped darkness turns to confusion at the appearance of Ghibli-like snake creatures.

Thankfully, all the superfluous elements are cleared away for the final scene. There’s just Chi, Yuu, and their realization of how much they love and need each other. It resolves and redeems all their conflicts and struggles up to that point. Amongst the ruins of a shattered city, Chi and Yuu are an inspiration towards cheerfully pursuing accomplishment for its own sake, beyond the immediate and regardless of the circumstances. In the empty modern world, that’s worth taking to heart. After all, the apocalypse has been and gone, and all of us are on our Last Tour.

Source: https://buttercupdew.tumblr.com/post/179768350293/girls-last-tour

Anime%20Among%20the%20Ruins%3A%20Girlsand%238217%3B%20Last%20Tour

Share

Enjoyed this article?

Be the first to leave a tip in the jar!

Related

-

A Forgotten Treasure from the 1970s: The Star Wars Holiday Special, Part 2

-

A Forgotten Treasure from the 1970s: The Star Wars Holiday Special, Part 1

-

Quiet on Set: The Dark Side of Kids TV

-

A Dystopia for Our Time: Nathan Fielder’s The Curse

-

When Perfect Families Go Wrong

-

How to Ruin a Good Kim Philby Story

-

Obi-Wan Kenobi

-

Mike Johnson and Diff’rent Strokes: When Liberal Narratives Collapse

2 comments

Girls’ Last Tour was by far my favorite series of last year. A lot of shows try to mix fun and drama–Ancient Magus’ Bride from the same season comes to mind–but typically I feel confused when these shows try to take some lighthearted turn. This is one of the few that do it well, though. There were a handful of episodes that were a bit meandering, but that’s television for you. Ironically, the literal meandering scenes–wide shots of the Krettenkrad rolling through the city with atmospheric music playing–were some of my favorite. The score captures a sense of hope that is truly a mere “glimmer” at most.

Consider doing a review of Re:Cyborg 009. It takes a hokey 1960s animated tv series and updates it for the modern era, with a plot centering on international terrorism and suicide bombings. An international conspiracy involving America, Israel, and the Iraq war are the primary reasons this might be of interest. I have never seen an anime outright name Israel in this way.

Comments are closed.

If you have Paywall access,

simply login first to see your comment auto-approved.

Note on comments privacy & moderation

Your email is never published nor shared.

Comments are moderated. If you don't see your comment, please be patient. If approved, it will appear here soon. Do not post your comment a second time.