Now in Audio Version!

Environmentalism & White Nationalism:

A Shared Destiny

Posted By

Michael Walker

On

In

Counter-Currents Radio,North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

To listen in a player, click here [2]. To download the mp4, right-click here [2] and choose “save link as” or “save target as.” To subscribe to the CC podcast RSS feed, click here [3].

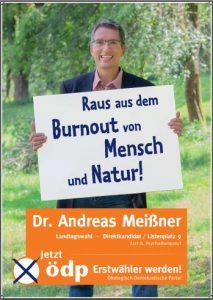

Andreas Meißner

Mensch, was nun? Wie wir der ökologischen Krise begegnen können

Münster: Edition Octopus, 2009

It often happens that polemicists assume radical positions in their writing or speaking which are poorly reflected in the lives they lead. The well-heeled socialist condemning inequalities of wealth and human poverty is too familiar to need introducing here.It is rather less usual to encounter the opposite, that is to say, someone whose individual practice is arguably more radical and engaged than his writing would suggest. This seems to be the case with Andreas Meißner, the author of Mensch, was nun? Wie wir der ökologischen Krise begegnen können (Man, What Now? How We Can Meet the Ecological Crisis), published in 2009, just after the financial crisis of the previous year.

Dr. Meißner is a psychiatrist by profession and his approach to the ecological crisis is a very personal one, personal above all in the sense that he addresses the reader personally as he, the psychiatrist, might address one of his patients, responding to the question, “What can I do about the environmental catastrophe which is overtaking the world?” For Meißner, the focus of attention in the foreboding times of impending environmental collapse is not how the world can be saved, but rather how can I – one man or woman, arriving at Dr. Meißner’s surgery for my first appointment – stay sane, remain optimistic, and retain or regain my psychological equilibrium? The doctor focuses in this book on what reads like and is intended to read like a patient-doctor dialogue, the sort of down-to-earth talk and thorough examination one would expect from a sympathetic and lucid psychiatrist. What can the “patient” do in face of the sense of impotence which the patient feels? This may sound trivial and of little relevance to the main issues of public concern, whatever we consider those to be, but it is not so. A sense of global challenge and global responsibility reflect the feelings of hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of middle- or upper-class whites who have a “social conscience,” who feel the world is not improving, but are at a loss to know how they can act more usefully and how they can “keep smiling.”

This book seems to me to be exemplary as a summary of the strength and failing of much of current environmentalist thinking. I disagree with very little of what is written in this book. It is what is not written that exasperates me. Dr. Meißner’s book seems to argue for political resignation, at least if politics means public activism. He insists that nothing much can be expected from politicians and that they have anyway missed the boat so far as bringing exploitation of resources to a halt before humanity reaches a point at which there will be a massive “bill” to pay in terms of disaster and catastrophe. The point has been passed, according to Meißner, and the bill is in the course of being presented. There has been no significant change in the attitude of mainstream political actors concerning economic growth, human expansion, and the physical environment since the earliest days of awareness, no realization that something was going very wrong with the planet in terms of long-term hopes for the survival of life (Meißner marks the points of no return as the oil crisis and publication of the Club of Rome report in the 1970s).

Meißner further remarks that politicians are not “leading the pack” in terms of ecological awareness, and that they are actually running behind the pack. Where measures are taken to clean rivers or recycle paper, with few exceptions such measures are the result of lobbying by Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and consumer groups, not decisions borne of politicians’ convictions. There are hundreds of groups and initiatives and widespread local awareness of the need to preserve the environment and prevent waste which is little acknowledged by leading politicians, who in their behavior seem to be quite contemptuous of the notion of sustainability or moderation. Have Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin, Nelson Mandela, Xi Jinping, Fidel Castro, or any other leading statesmen since the 1970s, whatever their politics, clearly expressed the existential threat posed to this planet by overpopulation and the accelerating depletion of natural resources in response to growing human demand? Not a hint. Is it surprising that their followers thus feel encouraged to ignore what should be obvious?

Dr. Meißner, who implies that political activism in the old sense is futile, makes no mention of his own political activities. He is in fact a prominent member and local candidate for the small ÖDP (Democratic Ecological Party), the German “Green” party which claims to stand “in the middle” of politics between Left and Right, in the knowledge that the much larger and well-established German Greens are on the Left. The first leader of the ÖDP was a man called Herbert Gruhl, author of Der atomare Selbsmord (Atomic Suicide) and Ein Planet wird geplündert” (Plundered Planet). Gruhl was a member of the German Bundestag for the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), but resigned in 1978 in opposition to his party’s pro-atomic policy. In an open letter to the government, he accused the CDU of continuing a no longer viable policy of economic growth as the focus of its political raison d’être. To this day, the ÖDP’s main reference point is a repudiation of the ideology of growth.

Growth is the ideology which underpins the statements and policies of most major political parties and movements throughout the world, so much so that favorable use of the term “growth” by a politician is a sure sign of that politician’s adherence to mainline politics. While paying ever more muted lip service to a questioning of the ideology of growth, the established pro-immigration Green parties of the West have come to accommodate themselves with those bodies, such as the EU, for whom growth and global equality are the highest and holiest ideals of political endeavor. Recently, in declaring support for a “sensible immigration policy,” a spokesman for the German Greens argued that qualified immigrants are badly needed by the German economy to “maintain the country’s strong economic position,” a remark which seems to accept the implicit ideology of growth that Green movements were originally founded to challenge.

Even a cursory review of the history of ecological movements will show that there has been a toning down of the original sharp critique of growth which was made in the 1960s and ‘70s before ecological parties all over the Western world made their peace with the establishment, and in doing so toned down the attacks on the belief in economic growth, and most notably ceased referring – as the Club of Rome and early writers like Paul Ehrich had done – to a human “population bomb.”

Like the party he represents, whose program, in the eyes of this reviewer, includes a good many sensible proposals but ignores the demographic elephant in the room, Meißner, who otherwise notes that the increasing specialization of modern education creates a “failure to perceive interconnectedness” (p. 85), is all but silent on the question of demographics. Needless perhaps to recount, he also entirely ignores the subject of race. It is my contention that race and demographics should be at the heart of all debate on the ecological crisis and that a failure to include them, or even to acknowledge them at all, explains the abject failure, on the one side, of the environmentalist movement as a whole, that movement which started out with such high hopes of changing the world when Green parties were first launched in the ‘60s and ‘70s, and on the other, the no less abject failure of white racial awareness movements to make any significant impact on the world stage in the last fifty years. Put simply, the Greens ignore race and population, and White Nationalists ignore the environmental crisis. Both thereby utter warnings which are true, but remain half-warnings only, and are only half-true.

This book is not a manifesto nor a call to arms, but as mentioned above, it is more like a talk with the individual reader. Need one say the individual reader is assumed to be (Greens never show the bad taste of actually stating this obvious fact!) someone from the cultured middle class or upper middle class, and indeed, for all the postured internationalism of Greens, they address their concerns to very confined audiences and readerships. Ironically, the Greens, who are so international in their clamor, can be quite provincial in their attitudes and perspective, and this book is a case in point. By its tone and references it is principally concerned with readers from the German-speaking area of Europe, and in fact many of the book’s references would be incomprehensible to readers unfamiliar with developments there. Meißner’s main argument is that humans are still psychologically programmed to think in terms of what in the evolutionary sense was necessary for survival and development as the species Homo sapiens, but that these in-built traits have become destructive urges in the global age. For example, whereas in the past humans would take advantage of abundant years or momentary plenty to fill themselves, now it is long-term planning and thinking which are called for. “Unconsciously-driven elements within us which influence our daily decisions draw close to an ancient system of reward and punishment which rated short-term reward higher than long-term advantage.” (p. 105)

The writer fails to mention studies and empirical evidence which point to the fact that this preference for short-term reward over long-term advantage is much more strongly felt among blacks than whites, and he could have mentioned the biblical lesson of the seven years of abundance and seven years of famine in Egypt, which precisely addresses the issue of long-term planning. But since the writer does not discuss race, he will likewise do nothing to examine the possibility that different peoples or different races may act differently in this respect. There is a case to be made – and many writers have done so – that the complete inability to plan for the future economically is a hallmark failing of the black race, and accounts in large part for their median low intelligence: a race that gazed at the ocean and yet never invented a sail, and that took fardels to market for centuries but never thought of the wheel. Everyone talks about the failure of Africa to feed itself, and nobody other than the small groups of racially-aware whites dare to mention the obvious fact, for which there is abundant evidence, that race may be playing a role in that failure.

The first part of the book is taken up with a discussion of the environmental crisis. Politicians, Meißner insists – and quite correctly in my opinion – are obsessed with growth. Economies are thus overheated, and resources depleted. There is nothing original here, perhaps, but unoriginal does not mean wrong or not worth stating. But what are the author’s solutions? After all, the title of his book points to proposals and solutions. Meißner claims that a global crisis is inevitable, and that climate change, the expansion of the desert, and fires and floods of growing devastation are just the foretaste of something greater and more awful still. Human society – movements as well as individuals – has willfully ignored crisis warnings in the same way that the individual patient – an alcoholic, say – ignores evidence of his addiction. Now it is too late. We cannot change the way the world is going, but we can adopt the right attitude to face the world in a state of equilibrium. The comparison with addiction is apt, for attachment to a belief in “growth” carries many of the hallmarks of a psychological addiction, a disorder of the psyche.

However, the crisis may be salutary, claims Meißner. Those who survive famine, wars, and worse will have learned a lesson. Here I detect an undercurrent of what the Germans call Schadenfreude, that disagreeable tendency to play the role of Ezekiel, of which Greens are often accused, not without some justification: He was a prophet chosen by the Lord who shook his hand and declaimed “I told you so!” as great cities were destroyed. The Bible abounds in such Schadenfreude. Meißner’s language is not biblical, but his assurance of catastrophe causes him to expect human population levels to plummet. His negativity even takes him to absurdly speculate about the validity of human life itself, as expressed in a convoluted argument about entropy – which this reviewer confesses he failed to follow entirely – in which he claims that mankind has been “wasting energy” since he first emerged from the confused struggles of early Homo and Australopithecus.

One subchapter of the book is even entitled “Arbeit ruinert die Welt?” (Work Ruins the World?): “Work can cause more damage than benefit when extensive energy is lost by being transformed into a condition which cannot be put to use.” (p. 93) The core of the writer’s argument here is that human beings should become more passive. Obviously, the less demanding and less active one is, the fewer demands one puts on the world. However, to argue thus far, as Meißner does, and not mention population is to take the (willful?) ignorance of the population issue to the acme of absurdity. What, after all, is more likely to reduce the stress of human energy on the world: the lowering of consumption, or a brake on the growth of, if not a reduction in, the human population? It is down that path that few environmentalists will go, and because they can or will not venture down it, they ultimately lack credibility in their proposals, because they ignore the most important aspect of the very subject they are tackling: namely, runaway human population growth.

Homo sapiens may be rotten to the core, but neither this reviewer nor any reader can own to being members of any other species. Not to embrace that fact and to despair so far as to question the desirability of human existence altogether is perhaps an easy temptation, but it means to slide into the full-scale nihilism of self-abnegation. To be fair to the writer, Meißner explicitly criticizes anything which might smack of self-hatred, at least at an individual level. On the contrary, he preaches love and empathy among all as prerequisites for future collaboration in solving the crisis. But it is indiscriminate love – which surely was never part of our genetic programming – that turns us away from the challenges of our time and prevents us from facing them as our forefathers would have faced any other danger: with a sense of reality and for facts, and with resolution.

Black Africa, whose population growth is so great and yet so little discussed, must be met with just that resolution and sense of reality which is natural to the survival of life itself. One race is increasing its population without showing that it can feed that population. Empathy in such a case is environmentally unrealistic, and insofar as others have a different sense of identity, suicidal. Put bluntly, what Black Africa needs is not empathy, but condoms. Such realistic language is, as all are aware, singularly lacking in Green movements. On the other hand, when even modest proposals are put forward by them – proposals woefully inadequate, but which are at least attempts to slow down runaway growth, if not to halt it – then the partisans of the ideology of growth kick in and cry “dictatorship.” To complete the blindness of our times, White Nationalists will be singing along with the chorus of the disciples of “growth forever, at whatever the cost.”

For example, when the German Green Party proposed a voluntary “veggie day” a few years ago – a day each year when people would agree to not eat meat – the Party was greeted with derision and howls of anger, from leading meat industry lobbyists, of course, as well as from many mainstream journalists, but from most “conservatives” and Right-wingers, too.

According to Meißner, a major crisis involving substantial population reduction may end up being the inevitable cure to the incompatibility of sustaining and feeding many billions of humans on a planet whose resources are, in the end, finite. Meißner’s emphasis, like those of nearly all Greens, is that of the stress of growing expectations. I have pointed to population growth. In fact, it is the grim convergence of the two which is destroying the planet. A few millions could live “like God in France,” with a high standard of living, so long as many more – billions indeed – were living like Indian peasants; the planet could cope with this. It is the notion that billions of humans should have a right (and they do claim that right, which the proponents of growth propagate unceasingly to them) to a living standard not of an Indian peasant, but of a Florida attorney; it is this double demand which is dealing our planet a fatal blow.

Is there no hope for political change, according to Meißner? Hope should be expected, the writer tells us – even while appearing to contradict his earlier message of hopelessness – from the major political parties, since they are most able to effect change. It is difficult to imagine a less radical argument than this. But there is a problem:

It is a tedious, strenuous, and above all long way to change something by political means, but along with the mark on the ballot paper, it is the only way. Unfortunately, in recent years the major parties which might have been expected to steer society in another direction have been whittled away by smaller parties, which represent only small interest groups and cannot be expected to adopt unpopular measures. (p. 160)

This is a strange argument in itself in that it assumes that the major parties are more than just an alliance of lobbies, and also naïve in thinking that they are likely to put unpopular measures into their manifestos. But coming from someone who himself campaigns energetically in a small party in Bavaria, presumably in the hope of taking votes from major parties like the Christian Social Union (CSU) or the Greens, this comment seems to be at odds with the substance of the author’s own political ambitions. I suspect that the writer cannot face the radicalism which it will be necessary to adopt if the premises of his own arguments are accepted. This, too, like much else in the book, is symptomatic. The Greens seem radical, but they cannot take the last radical step and proclaim their break with global capitalism and the global growth project and New World Order which is behind it all.

What is important about the book? In itself, I do not think the book has much, if anything, original to say or even to suggest, but it is a very telling and revealing exposition of what is admirable about the modern awareness of the ecological crisis among the educated classes of the West, and at the same time of what I would say are the fatal limitations of Green awareness.

Two paradigms or prognoses which are frequently dismissed and derided for having been fatalistic and hopelessly wrong are the Marxist and the Green projections, Malthus appearing as the first and most famous proponent of the latter. As is well known, the Marxist projection was that the internal contradictions of capitalism would eventually force the world economy to a crisis point, leading ultimately to capitalism’s collapse. The second, more famous projection was that made by environmentalists in the 1960s and ‘70’s about the inability of humanity to feed itself in the wake of the population explosion. Paul Ehrlich famously predicted in his Population Bomb that overpopulation would lead to the deaths of hundreds of millions by starvation already in the 1970s.

The liberal globalist interpretation of the failure of these predictions is that they were based on false premises. But it is not so much the paradigm or mathematical logic which can be questioned here as – and this is what it seems to me the supposed failure of both projections have in common – the underestimation of mankind’s ability to respond to impending crises by plundering the planet more effectively than ever before. Ever-growing populations are fed and allowed to increase, and rising real wages keep the non-property-owning classes happy. The price of all this is only mentioned by the feisty Greens. Mankind is drawing not on an interest in staving off crises, but on capital (a particularly well argued point in this book), and essentially, the dire predictions which were made have not been confuted, but delayed. Small groups of (mostly white!) scientists work to find new ways of feeding the ever-increasing millions and new ways of exploiting resources more effectively. However, the apparent failure of prediction and the hyperbole of some writing and talk helped turn Green movements away from the subject of population and toward concentrating on the Left-wing slogan which now dominates Green agendas: the “fair” distribution of resources. The world is not overpopulated at all, the argument goes; it is just that resources are not fairly distributed.

In the 1980s, there was a switch from focusing on population growth, as illustrated in the Club of Rome’s Limits to Growth (1972), Ehrlich’s Population Bomb, and Garrett Hardin’s Tragedy of the Commons (both 1968) to concentrating on energy conservation, renewability, and resource distribution, along with urging a small class of affluent “socially aware” persons that they should behave with a strong sense of social responsibility. Mensch was nun? is a reflection of such an individualistic approach to environmental problems.

Meanwhile, environmentalist NGOs and Left-dominated Green parties moved from indifference into downright hostility towards any discussion of a population problem, a problem which they now hardly deign to even acknowledge. An early Green campaigner in Britain, and co-founder of the British Green Party, Jonathon Porritt, is an exception among Greens of the “second generation” in that he has continued to campaign on population matters, and has written on his blog about population growth, mentioning that he is “baffled” by the refusal of NGOs to discuss population growth as an environmental issue. Does he really not understand that this is because the population and race issues are interconnected? Porritt writes [4], “This is an issue that still preoccupies me enormously, and I still remain completely baffled as to why it has been considered all but irrelevant by most environmental NGOs.”

The answer can already be found in the one outstanding, but decisive, failing of Ehrlich’s Population Explosion. As with Mensch was nun? and so much of Green discourse, the problems are well-defined and persuasive. The resources of the world are diminishing, entire animal species are disappearing, the wilderness is shrinking, and immense stretches of water carry shimmering masses of human garbage. The litany can be extended. It is deeply depressing, and Meißner is right to point out that many people avert their gaze sooner than look on this rising level of waste and desolation. Humans – non-white humans, that is – continue to multiply at staggering rates. Despite some attempts to curb population growth in India, the population is now 1.324 billion, while at the end of 1968 it was “only” half a billion. The population of Nigeria is currently at 196 million, and rising fast. In 1968 it was 53.6 million. In the meantime, whites are hardly reproducing at all. Every few years, the population of the entire world increases by more than the populations of Britain, France, and Germany put together. Unbelievably, the Ehrlich solution was that at least Western-educated people (viz. well-to-do whites) could cut down on the number of children they were having, even if fertile blacks were disinclined to take this step.

The subject which nobody wants to discuss, but which explains the failure of the environmental project, is race. The population explosion is the explosion of non-white races who have to date produced little environmentalist initiative (there are honorable exceptions) shown in white countries. One might expect that at least those small groups in white countries and parties which are to a greater or lesser extent aware of and concerned with the decline of the white race would be similarly concerned with the population time bomb and its global environmental consequences, and understand the interrelatedness of environmental catastrophe and non-white demographics. It is not so. They will tut and shake their heads, perhaps, before returning to their preferred topics of the survival not of the planet, and not the fauna and flora of the Earth, but simply of the survival of the white race alone. In reading much of their literature, one gains the impression that this is all which concerns them. The planet can quite literally go to hell. It is.

Broadly speaking, it can be said that environmentalists and “White Nationalists,” or whatever one should call those aware of and fighting for a separate white identity, are cogent and persuasive in perceiving a major problem in the world, but inadequate and unconvincing in offering ways to meet the challenges they describe, because each is blind in one eye. Environmentalists react allergically, as Western society in its entirety is programmed to do, to anything which smacks of racial differentiation (“racism”), whilst those who are racially conscious strike what is usually no more than an insincere pose – one without substance or seriousness – on the subject of the environment.

The absence of even a mention of the population issue in Meißner’s book illustrates the dire poverty of the Green position, just as the absence of any mention of environmentalist issues in Right-wing populist programs (Nigel Farage recently posted a Facebook photo [5] of himself having caught a protected species of shark with the heading, “Feeling depressed about the way Brexit is going so went fishing” – a sadly telling example of this one-sidedness) is not only inadequate, but it is my belief that it ensures the ultimate failure of both movements. By excluding one another, they ultimately ensure their own lack of credibility and ultimate ineffectiveness.

The fact is that the two developments, the two disasters, and the two causes of a potential complete collapse of human order and perhaps even human survival is attributable to the failure of a broad racially- and environmentally-aware consciousness to emerge, and subsequently merge. Working apart, each is condemned to ultimate failure, because each is then disregarding a key element which makes sense of the development which it deplores. Whites are being overrun by a numberless human tide of non-white “global citizens” who not only do not possess the abilities to ensure civilized or democratic order, but who have also to date displayed none of the scientific ability, acumen, and long-term planning needed to cope with the environmental challenges which this book describes. So long as environmentalists ignore this fact, they are at best deferring disaster, not striking at the root cause.

Similarly, to be aware of that root cause and yet not strive against all initiatives aimed at degrading the environment or shrinking wilderness, replacing green with concrete, and not to seek in the long term a rewilding of the planet, a restoration of the planet’s abundance and variety of life, ensures that white consciousness remains little more than a hobby of resentment. The title of Dr. Meißner’ s book is Man, What Now? My answer is: environmental degradation and population explosion constitute the two sides of one and the same challenge and disaster. It is time to connect the dots.