Imperium:

American History X Meets Harry Potter

Posted By

Howe Abbott-Hiss

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

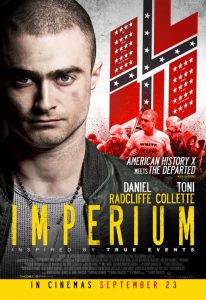

Imperium (2016)

Written & directed by Daniel Ragussis

Starring Daniel Radcliffe, Toni Collette, Tracy Letts, & Devin Druid

Imperium bears some similarities to the 1998 film American History X, which has the same theme. Both come across as attempts to demonize white identity by associating it with unsavory characters. But while director Tony Kaye’s film starring Edward Norton attempted to humanize the “racist” protagonist, even ultimately making him the hero of the story, Imperium at best inspires pity for its pro-white characters. Ultimately, it is more similar to the Harry Potter series, for which lead actor Daniel Radcliffe is more famous – and it is no more realistic in its portrayal of heroes and villains.

Radcliffe plays Nate Foster, an FBI agent assigned to infiltrate a “white supremacist” gang in order to gain access to a radio host who is considered a potential terrorist. Foster is described as the son of a single mother, an introverted victim of bullying with a history of social isolation.

Toni Collette stars as Angela Zamparo, an intensely unlikable agent who seems perpetually bored, as if she is being forced to give remedial instruction to a moronic student. Zamparo is responsible for Foster’s assignment, deeming him, over his own objections, to be the right type of man for the job.

[2]

[2]Agent Zamparo gives Foster a characteristically charming look as he practices his new “racist” persona.

It quickly becomes obvious that this is an immature superhero fantasy in the same vein as Harry Potter. As in superhero stories, the hero is chosen by a lucky stroke of fate beyond his control, while his enemies are not people with legitimate interests but are simply terrifying personifications of dark forces, or at best hapless buffoons being exploited by immoral actors. This is extremely flattering to anyone who identifies with the hero, but is about as realistic as fantasies about being King of the World.

Similarly to Foster, with his unhappy childhood, Potter was an orphan adopted by abusive relatives and isolated in a closet until the age of 11. Like Foster, Potter was unwillingly thrust into the role of a hero. He was admitted to the Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry without knowing of its existence, at which point he was already a celebrity due to Lord Voldemort’s unsuccessful attempt to kill him when he was an infant.

Further parallels to Harry Potter can be seen in the villains of both stories. Voldemort’s followers are described by J. K. Rowling as a combination of the ambitious seeking shared glory, the weak seeking protection, and the thuggish admiring a leader who can show them new refinements of cruelty. Nothing about their motives is respectable; beyond cruelty for its own sake, they simply represent lust for power and cowardice.

Similarly, the “white supremacist” and neo-Nazi groups in Imperium are introduced by references to convicted terrorist Timothy McVeigh’s alleged plan to start a race war based on the exterminationist fantasies in The Turner Diaries. No explanation is given for this level of hostility towards non-whites beyond his being a “white supremacist” who had read a violent book. Zamparo is at pains to explain that he was “not insane,” but the viewer is left to assume throughout the film that he and other “white supremacists” have no legitimate reason for being concerned about race. A desire for self-aggrandizement and indiscriminate vengeance are presented as the reasons for other characters’ involvement in the movement.

[3]

[3]The Ku Klux Klan, like the neo-Nazi groups in the film, is depicted as alternately threatening and ridiculous.

Both sets of villains are depicted as blindly “racist,” proud of their own group and contemptuous of others for illegitimate reasons. Voldemort’s Death Eaters boast of having “pure blood,” meaning no non-magical ancestors, and look down on “mudbloods,” while heavily mixed blood is actually universal. The neo-Nazis and Klan members in the film are depicted as having only a shallow pride in their race, largely a matter of boasting, with little reference made to actual racial differences or anything else which could explain and justify a sense of white identity.

Interestingly, the closest the film gets to engaging with racial differences is in a scene where Foster meets with a quieter and more intellectual member of the movement. This man, an engineer named Gerry, appreciates European composers such as Brahms and points out proudly that the white man made the modern world. This point is dismissed with a montage including marching jackboots, implying that the viewer should not be proud of this fact because the modern world included the Nazis.

Gerry further explains that he once worked as a contractor in Kenya, which was presumably the first time he was exposed to black people in their own countries. He expresses disgust that the Kenyans lived in their own filth, suggesting that even animals would not live in such conditions. Of course, public defecation and lack of sanitation is a real phenomenon in Africa and in other Third World countries such as India, but this point, too, is dismissed. Foster’s response implies that it is an outrageous claim, as if Gerry was fabricating it all. He wonders out loud how he can possibly reach people who think such things.

[4]

[4]Gang leader Vince Sargent. Sigrune tattoos on the face or neck have apparently not gone out of style since American History X.

In order to infiltrate the neo-Nazi gang led by the neck-tattooed Vince Sargent, Foster takes on the persona of a simpler man who served in the Marines with a WMD squad in Iraq. He abandons his glasses, shaves his head, and starts reading literature in line with an anachronistic and extreme view of white identity such as Essays of a Klansman and Mein Kampf, underlining passages such as “terror can only be broken by terror.” Although some “white supremacist” characters are depicted as people with respectable jobs and no criminal records, the film is full of deliberately frightening or outlandish imagery, reinforcing the implication that white identity is simply a matter of concern to neo-Nazis and Klan members.

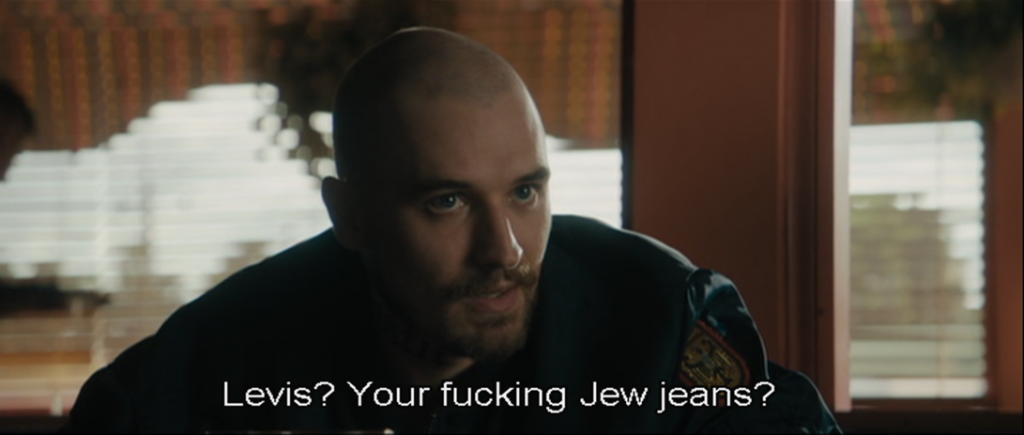

In line with the type of “white supremacy” which is dismissed today by white identitarians as “LARPing,” the first words gang leader Vince utters to Foster are “1488, brother.” He sees his group as successors to the National Socialist paramilitary group known as the Sturmabteilung, and mispronounces the word to emphasize to the viewer that he is not as smart as he thinks he is. One of Vince’s followers is cartoonishly anti-Semitic to the point of being offended by Foster’s pants; he aggressively interrogates him about his Levi’s, or as he calls them, “Jew jeans.”

Foster speaks to a young member of Vince’s gang in a scene reflecting popular stereotypes about why anyone would choose to be pro-white. Johnny explains that he was often bullied in school, and expresses his humiliation at seeing a friend of his brutally beaten by a gang of gentlemen of color while he did nothing to protect him. He is happy to observe of his new friends that, “With these guys, nobody can do shit to me,” and boasts that “I learned to be proud. Strong!” in a tone that makes the viewer imagine a narrator’s voice explaining, “He was not actually strong.” Johnny is one of the “weak seeking protection” who in Rowling’s work would have joined the Death Eaters.

[6]

[6]In the upcoming Harry Potter and the Black Friend, Harry fakes contempt for muggles while undercover with the Death Eaters.

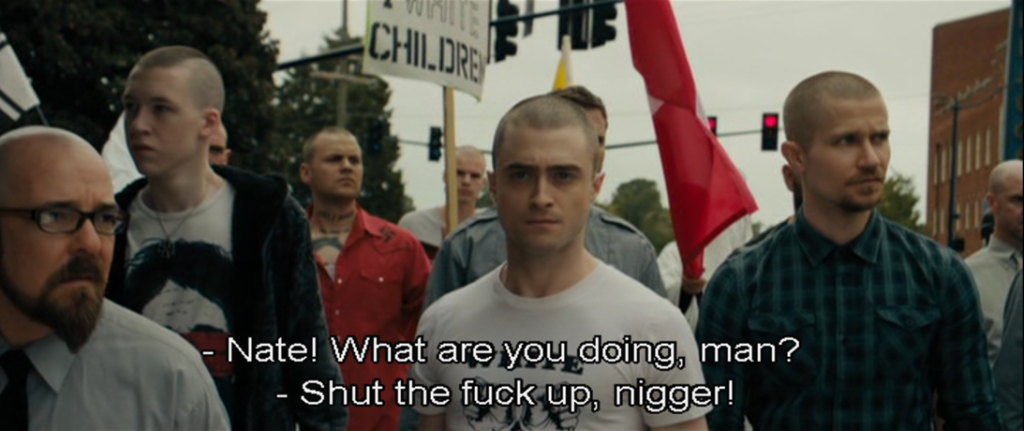

In a welcome nod to reality, there is no denial here that the Antifa are violent. In a scene where Vince, Foster, and another leader named Andrew Blackwell attend a White Nationalist march, there are indeed numerous black-clad and masked men belonging to an “anti-fascist” group looking for a fight. After Blackwell is assaulted and injured, Foster attempts to evacuate him in his car. The Antifa attack the car, smashing the windows and windshield with hockey sticks in a foreshadowing of the James Fields incident, although Foster is ultimately able to get away without hurting anyone.

Another interesting concession to reality is that the authorities are shown as overzealous in dealing with “racist” suspects. Although they ultimately uncover and foil an actual terrorist plot involving Gerry, the FBI agents spend quite a bit of time pursuing a clownish, pro-white talk radio host known by the pseudonym of Dallas Wolf. Their interest in him is based on a paranoid interpretation of various clues involving his radio commentary and his home life. Foster is so aggressive in trying to get him to explicitly commit to a terrorist plot that Wolf actually contacts the FBI to report him.

[7]

[7]A frame from a Dallas Wolf video, attempting a swastika in the illustrious “Hail Hortler” tradition.

Under interrogation, Dallas Wolf reveals that none of the issues he preaches about actually matter to him; his motive seems to be nothing more than self-aggrandizement, and he sees his fans who believe in what he says as idiots. This is in line with the disconcertingly common view that not only is disagreement with various egalitarian dogmas immoral, but those expressing dissenting views are either cynical demagogues or dupes.

The movie ends with an embarrassing explanation for what gives rise to white identity politics, or “fascism,” as Agent Zampora calls it. “It’s victimhood,” a penitent Johnny explains to a classroom full of children, while Foster looks on. “I was going to hurt everyone else the way they hurt me.” But he advises the attentive children that they do not need to have a victim attitude themselves. In an implicit condemnation of racial identity, Johnny tells the non-white children, “When I look at you, I see myself.” Foster tells Johnny he is proud of him.

This is similar to American History X’s infantile condemnation of “racism,” as in both films no real reason is given why concern for the white race is illegitimate. The protagonist, Derek, is a tattooed neo-Nazi who goes to prison for manslaughter and is changed by his experiences. He meets a black prisoner who is friendly towards him and not intimidated by his “racist” views. He also finds, not surprisingly, that members of the prison gang he has joined, known as the Aryan Brotherhood, have dealings with non-white gangs. In response to his mild criticism of this, they gang-rape him.

Derek is disillusioned with the entire idea of white identity after this, but how this proves that his previous racial views were wrong is never explained; it is on the level of saying that the existence of pedophile priests disproves Catholicism. Previously, he was able to articulate reasonable complaints about the effects of illegal immigration on taxpayers and workers, and he has plenty of experience with black criminality, including his father being murdered by blacks. But in condemning the movement in front of other neo-Nazis, he has no argument other than to call his previous views “bullshit.”

[8]

[8]Foster addresses Johnny, reminding the viewer of the social benefits of renouncing one’s white identity.

Johnny’s final speech at the end of Imperium is literally a lesson for small children, and it is obvious that the movie’s writer-director was unwilling to deal with the issues on an adult level. Instead, there is greater shallowness and cowardice here than in American History X; in the previous film, the creators at least did not shy away from depicting actual black-on-white violence and criminality.

Daniel Radcliffe has been quoted [9] as saying he has “always hated anybody who is not tolerant of gay men or lesbians or bisexuals.” Interestingly, neither the character of Foster nor the film overall express the same outright hatred for “racists.” There is no attempt to justify violence towards them on the part of the Antifa or anyone else, nor any implication that they should be punished for expressing their views. Agent Zampora even advises Foster to “try relating to these guys as human beings,” explaining that “you may have more in common with them than you think.”

On the other hand, the film does not take its own advice very well. By avoiding any real engagement with the concerns of “racists” and portraying their motives in Harry Potter terms, it does little to address the frustration or alienation that in rare cases might lead to violence. The film does not dispel the popular belief that white identitarians are at best simply deluded; it continues the gaslighting that so many find infuriating.