I Saw the World End:

Wagner’s Ring in Munich

Posted By

John Morgan

On

In

Counter-Currents Radio,North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

To listen in a player, click here [2]. To download the mp3, right-click here [2] and choose “save link as” or “save target as.” To subscribe to the CC podcast RSS feed, click here [3].

Seeing an opera production these days, if you’re anything even approximating a small-t traditionalist, is always a risky business. When the guardians of Western culture – who actually hate Western culture, or at least what it was until recently – want to change literature, painting, television, or film to suit whatever agenda they’re pursuing at the time, it’s a relatively simple matter: they simply create new works in new styles. But opera, drama, and classical music are harder nuts to crack, since the one rule in those genres that is still (usually) held sacrosanct is that any production must remain true to the text and the music as originally written. Given that many of the most popular operas, plays, and music that continue to be performed date from before the twentieth century, when our culture was horribly Eurocentric and obsessed with such passé ideas as beauty and truth, the only stratagem available to deal with the former two has been to come up with bizarre stagings that undermine the original intentions of their creators. (As for classical music, they have yet to come up with a workable plan of attack, although recently I’ve noticed an increase in calls for “greater diversity” in classical music, since the vast majority of composers, conductors, and performers of music played on classical instruments are still white people, amazingly enough. If that doesn’t work out, I imagine that eventually groups dedicated to such music, which invariably are heavily dependent on state subsidies to survive, will simply be defunded in the interests of “overcoming racial/gender normatives” or some such thing – although hopefully the current cultural regime will collapse before that happens.)

Before I sound like a fogey, however, I should say that I am not opposed to innovation in productions. I understand that producers and performers do not want to put on operas and plays in exactly the same manner, in all the many venues across the world, year after year. Such an approach would stifle creativity and quickly become stale, for the audiences as much as for the people putting them on. (Although it is certainly the case that Wagner’s own family favored such an approach; during the initial performances of the Ring that he supervised himself, the gestures and stances of the performers were codified and religiously followed in every production at Bayreuth for decades afterwards.) And one should not forget that Wagner himself was a radical innovator in his day who angered many cultural conservatives with his “music of the future,” and was reported to have once implored his performers at a rehearsal: “Children! Make it new! New! And again new!” Still, I do feel that producers have an obligation to be faithful at least to the spirit that a work was created in, and it is certainly the case that many contemporary productions, in their zeal to be new and different, cross the line in this regard, resulting in performances that are either confusing or simply ridiculous. As I’ve heard many theater- and operagoers say, it’s a problem if a production is so strange that, if a person who had never seen the work before were to see it, he would be unable even to figure out what is supposed to be happening on stage. Such performances are self-indulgent on the part of the producers and only reinforce the already common perception that theater and opera are closed worlds reserved for an elitist cult that thumbs their noses at the poor slob who comes simply in order to find out what all the fuss is about.

Unfortunately for Wagnerians such as myself, the works of Richard Wagner are particularly singled out for such treatment. This is undoubtedly because of Wagner’s notorious reputation as “Hitler’s favorite composer,” and the well-known fact that Wagner himself was both a German nationalist and an anti-Semite; some producers seem to eagerly look forward to getting his music-dramas into their clutches, in order to “redeem” him or else simply to drag him through the mud in retribution. The door for this was opened at Wagner’s own Festspielhaus, or “festival house,” in Bayreuth, Germany, which was established by the composer himself, with the considerable financial support of King Ludwig II of Bavaria and the coffers of the Bavarian state, and where since Wagner’s day his works have continued to be performed each summer, supervised by his descendants. Since 1945, the Wagner family has been continually looking for ways to atone for the close relationship that the Festival, and in particular Wagner’s daughter-in-law, Winifred Wagner, had had with Hitler and the National Socialists during the Third Reich. In 1976, Bayreuth presented a new “Centenary Ring” to celebrate the centennial of the first performance of the complete Ring Cycle. The production was designed by a Frenchman, Patrice Chéreau, and broke with the usual Wagnerian conventions of utilizing a fantasy-medieval aesthetic à la Lord of the Rings in favor of a more modernist presentation, setting the Ring during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and drawing on a socialist reading of the work as being about class conflict and a critique of capitalism that had first been formulated by George Bernard Shaw in his 1898 book, The Perfect Wagnerite. By today’s standards, the production (which is available on DVD) seems rather conservative, but it provoked a storm of controversy in its day, with many Wagnerians condemning it for imposing a vision on the work that Wagner had never intended. (In my opinion, however, it falls within the bounds of acceptability, given that this reading of the work is certainly valid both in light of Wagner’s documented youthful enthusiasm for socialism and anarchism, as well as by indications within the text itself.)

In the more than forty years since then, the situation has only gotten more problematic. I’ve now seen five complete Rings live, and have viewed or listened to innumerable others on video or disc – some recent productions have been terrific, some have been godawful. The best of the productions that I have seen on stage was undoubtedly the Austrian producer Otto Schenk [4]’s, which was performed at New York’s Metropolitan Opera several times between 1987 and 2009, conducted by James Levine, and which was based on the design of a Bayreuth production from 1897. It was the first complete Ring I ever watched on video (or in any other form) when I was young, and I was fortunate to see it on stage in 2000. The reason it remains my favorite isn’t simply for the performance, which is indeed fantastic, but also because the staging was entirely traditional, with nothing strange, out-of-place, or distracting in it. It may not, perhaps, be the best Ring ever recorded – most Wagnerians have strong opinions on such matters, and usually date the best performances to the mid-twentieth century – but it still remains the one I would recommend to a newcomer to the Ring simply because it remains distinctive among all those available on video of being the only one with a traditional staging – and indeed, when it was being performed in New York, some critics condemned it for its “unoriginality,” simply because already by the late 1980s it had become unusual to see a Ring that actually remained true to Wagner’s original vision. Such productions are even rarer today, and as much as it pains me to say it, I wouldn’t recommend to a Wagner or Ring newbie to see any of the performances of it being offered at present without being certain that it’s one of the rare “traditional” ones. (See this review by Jef Costello [5] of the Metropolitan Opera’s current Ring production.)

One of the worst examples in my own experience is, unfortunately, the current production on offer by the Hungarian State Opera that has been ongoing since 2015. In Das Rheingold, the gods were presented as the owners of a shopping mall, with what appeared to be screen-savers of coupons being projected against the backdrop, and it ended with Wotan and his pantheon preparing to enter Valhalla while pushing grocery carts in front of them. Die Walküre was even worse, with the conflict between Hunding and Siegmund being depicted as something out of West Side Story, with Hunding as a cheap mafioso in a modern suit who, when Wotan takes his life with a word using the chilling command of “Geh!”, simply shrugged his shoulders and strutted offstage as if he were a drunken frat boy being kicked out of a bar by a bouncer. The evening hit rock-bottom when the Valkyries appeared on stage at the beginning of the third act to the accompaniment of the famous “Ride of the Valkyries,” here presented as dominatrixes, garbed in leather S&M costumes and twirling whips above men lying prostrate on the ground. (Greg Johnson, who happened to be with me that evening, wisely walked out at that point, leaving me to suffer through the rest alone.)

Perhaps (one hopes) the climax of smearing Wagner’s work occurred in 2013, during the bicentennial celebrations of Wagner’s birth, when the Düsseldorf opera house, perhaps thinking that they could make a name for themselves by being the most extreme, commissioned a production of Wagner’s Tannhäuser that was set in a German concentration camp, complete with on-stage rapes, head-shavings, shootings, and gassings. This staging was developed by one Burkhard Kosminski – one can imagine him chuckling to himself before its premiere at the thought of putting one over on the German audience by throwing their own “guilt” in their faces, believing that they would be too terrified of being accused of Nazi sympathies to say anything against it. Fortunately, Kosminski and his backers were wrong. The Düsseldorf audiences roundly rejected the production, with many booing and walking out during the performance. When the house asked Kosminski to tone down some of the worst elements of his design, he refused – and fortunately, after only a few performances, the production was permanently shut down. It was gratifying to learn that German operagoers were willing to stand up and show that enough was enough and that they were not willing to accept having Wagner besmirched and their own noses rubbed in their alleged complicity in crimes that had occurred seventy years earlier.

Given all of this, it was with a mixture of trepidation and excitement that I took the trip to Munich to see the Bavarian State Opera’s production of the Ring last week. While I consider Parsifal to be the most moving of Wagner’s music-dramas, the Ring [6]holds a special place in my heart, not only because it was the first of Wagner’s works that I really engaged with, but also because it is the one that is most closely bound up with Germanic mythology [7]. I can never think of Wotan without remembering James Morris’ decisive gestures and derisive laughter, and hearing Wagner’s “spear” motif [8] in my head. Julius Evola took Wagner to task for adapting and injecting modern ideas into the ancient myths. This is certainly true, but it remains an incredible work of art in its own right, and I would contend that it remains true to the spirit, if not to the letter, of the Sagas. But nevertheless, an opportunity to see the Ring live is always a cause for celebration, given that, as Shaw himself once said, even if the production itself is terrible, you can always close your eyes and just listen to the music. Not to mention that it was only because of the generosity of my father, who got me the tickets to this particular Cycle as a birthday gift, that I was able to attend at all; I was informed that when the tickets went on sale, there were eighty thousand people trying to purchase approximately two thousand available seats. But experiencing the Ring, either in recordings or especially live, certainly demands a lot from the listener, given that it takes sixteen hours to see the entire Cycle, over four nights. It’s not for the attention-deficit or low-stamina crowds – but then neither is any part of authentic Western culture.

By the end of the Cycle, my verdict was that the performances by the singers were mostly incredible; the orchestra was good; and the staging was variable, ranging from intriguing to the ridiculous. But what follows is a more detailed report, going night by night. The production of the Ring that I saw, and which has been running at the Bavarian State Opera since 2012, was designed by Andreas Kriegenburg. In what follows, I will presume that the reader is already familiar with the basics of the story and characters of the Ring – it would make this essay far too long to include a synopsis of such a massive work, and many are already available both in print and online, if needed.

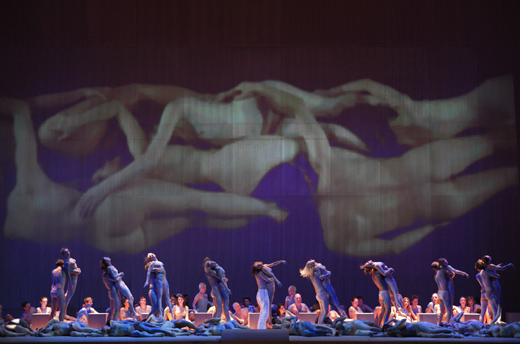

Das Rheingold, it must be said, did little to assuage my fears. Before the performance even began, while the audience was still taking their seats, a large number of men and women sat on the stage, chatting casually with one another in their underwear. Then, just before the music began, a woman came out and began painting one of the men with blue body-paint; all of the people on stage then proceeded to smear each other with the stuff. The reason for this became clear when the music began. The initially subdued, then slowly increasing in volume and complexity, opening bars of Das Rheingold are usually interpreted as a musical depiction of the creation of the world, especially the Rhine river, which features prominently throughout the Ring’s story. (Hitler himself once commented, as recorded in his Table Talk: “I imagine to myself that one day Science will discover, in the waves set in motion by the Rheingold, secret mutual relations connected with the order of the world.”) These dancers then formed a human chain on the stage and began emulating the movements of water flowing in a river, setting the scene for the opening of the drama, which is set at the bottom of the Rhine. Yes, I will concede, in its own quirky, fourth-wall-breaking way, this is in keeping with Wagner’s intentions, but still, it seemed as if Kriegenburg was screaming at the audience, “Look at how avant-garde this is going to be!” It was a bit off-putting.

As the first night continued, I found that John Lundgren made an excellent Alberich – he played the role with a more human, and less of a cartoon villain’s, sensibility than is typical. To give but one example that stood out for me, when one of the Rhinemaidens mocked Alberich’s ugliness, he chuckled in a self-deprecating way, rather than grimacing and shaking his fist as he is often played – and ultimately, Alberich, for all of his dwarvish nature and monstrous cunning, is in the end a symbol of human frailty, so I found it an interesting performance. Wolfgang Koch as Wotan, however, left something to be desired, both as a character and as a performer. Throughout this Ring, the gods were depicted as scheming business executives in modern suits, waited on by servants in tuxedos: the Germanic gods as plutocrats, something which has been a common motif in Ring productions since 1976. But Koch played Wotan as a rather meek, aged, and pliable CEO, rather than with the forcefulness and energy of one who is, after all, the ruler of the universe. Unfortunately, Koch’s voice proved to be rather weak as well – either he was having a bad week, or he’s past his prime, but the strain was evident on more than one occasion.

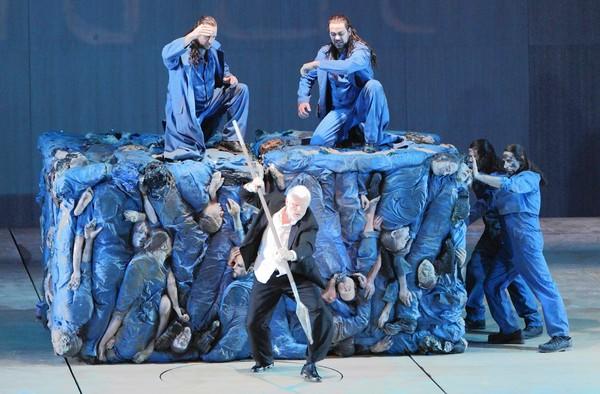

The dancers who had at first formed the Rhine went on to form all of the other structures during the first night, such as Valhalla. It seemed to me that they were meant to represent the forces of nature, although the way they sometimes swirled around the characters on stage was distracting at times. The Rhinegold itself, when still in a state of innocence at the bottom of the river, was depicted as a human as well, covered in gold paint; when Alberich stole it, he simply slung the body over his shoulder and carried him offstage. Later, in Nibelheim, the dancers became uniformed workers slaving away to mine gold to produce the weapons with which Alberich was planning to take over the world. Periodically, one of them would die, and his body would be thrown into the forging pit with a bright flash. And when Fasolt and Fafner, the two giants who constructed Valhalla by contract with Wotan, arrive to demand their pay, they are not of unusual size: rather, they are the size of ordinary men, but standing high atop cubes made up of dead bodies. It may be a bit on the nose as a symbol, but the meaning is clear: the achievements of industrial civilization are built atop the bones of its victims.

It wasn’t a terrible production, but I didn’t find it very satisfying, either, and I came away from the first night wondering what else we were in store for during the remaining nights. Fortunately, I needn’t have worried, as it turned out that this was the low point of the Cycle.

Die Walküre was the highlight everyone was waiting for, as it featured two superstars of the operatic world: the Munich native, tenor Jonas Kaufmann, as Siegmund, who is perhaps the most celebrated tenor in the world today; and the Swedish soprano Nina Stemme as Brünnhilde, in a role which she has made her own in several legendary performances. Both of them comported themselves admirably, with Kaufmann bringing an energy to the part that made it a memorable performance, as did Anja Kampe as Sieglinde and Ain Anger as a superbly loathsome Hunding (Anger also played Fafner on the other nights). The prelude was accompanied by a silent depiction of the battle between Siegmund and Hunding’s family on the stage, something that is usually only described later, in the narrative dialogue. In the fight, the warriors who get slaughtered are dressed in tuxedos, just like the gods’ servants, showing that Hunding, too, is a plutocrat of some sort, lording it over his workers and using them to fight his battles.

But again, the staging proved to be an obstacle to appreciating the drama. The first act is the story of how Siegmund and Sieglinde fall in love, but on this occasion, the army of dancers were dressed as what appeared to be servants, and whenever Sieglinde offered refreshment to her new love, the two stood at opposite ends of the stage, and the servants would pass objects back and forth between them. This came dangerously close to crossing the line of respecting Wagner’s intentions, as the libretto says that the two are supposed to be gazing into each other’s eyes – this was impossible in this production, given that there were servants bustling back and forth between them the entire time. Also, for a reason I could never fathom, these servants were all carrying small lamps in the palms of their hands, and when Sieglinde referred to the glint of the sword Nothung buried in the tree inside the house, these “servants” all simultaneously directed the beams of their lights towards the sword, in a gesture that was so painfully overdone that I couldn’t help but chuckle out loud when it happened.

The most controversial part of the staging of the entire Cycle didn’t come until the opening of the third act; it has become so notorious, since the production’s premiere in 2012, that I had already heard about it. It had been so poorly received in the past that many in the audience who I spoke with were wondering if perhaps the producers had decided to remove it altogether – they hadn’t. Before the music even began, a group of female dancers came out on the stage, who we were eventually to figure out were supposed to be the Valkyrie’s horses, even though they weren’t costumed as horses in any way. They danced around the stage in a wild manner for quite some time amidst the bodies of men in tuxedos impaled atop spears, obviously meant to symbolize the dead warriors destined for Valhalla; I never looked at my watch, but I would estimate that this absurdity lasted for at least ten or fifteen minutes (perhaps it only felt that way). Many in the audience booed or shouted angry protests at the stage – not that it did any good, but at least people made their feelings known. My father whispered to me at one point, “Well, this is certainly one way to make Wagner even longer . . .”

Once the horse-dancing was finished, perhaps the most beloved sequence of the Cycle was allowed to proceed: Wotan’s reluctant and loving condemnation of his defiant daughter Brünnhilde to sleep until she is awakened by a hero brave enough to cross Loge’s flames to reach her; after that, she will belong to him forever, and Wotan will never see her again. This act, in which Wotan has to do a lot of singing in his argument with Brünnhilde followed by a long aria, is notoriously brutal on the vocal chords, and Koch was most evidently not quite up to the task. The strain in his voice was audible at times, and during his debate with Brünnhilde he paced around the stage with water bottles in his hand that were brought to him by servants, which he would occasionally toss away in anger – afterwards, those of us in the audience debated as to whether this was an intentional part of the staging or if they had worked it in at the last moment when they realized that Koch was on the verge of a laryngeal crisis. Nevertheless, he more or less made it through, and the emotional power managed to seep through regardless of these flaws.

Siegfried brought with it the wonderful performance of Stefan Vinke in the title role, who looked every bit the part of the naïve yet fearless hero: frequently flashing a broad grin and wearing a sleeveless tunic which showed off his appropriately muscular arms, which he exploited to ham it up at one point by making use of Mime’s forging equipment to lift in time to the music. Vinke definitely gave the aptly-named Siegfried Jerusalem, my previous favorite Siegfried, a run for his money. Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke was perfect as the always-suffering and whining Mime (the character most students of Wagner agree was likely intended as a Jewish caricature), simultaneously irritating and backstabbing, with no moral scruples of any kind in his pursuit of absolute power. And Ain Anger again appeared as Fafner, this time in the form of a dragon. The dragon is always the trickiest part of any production of the Ring, since even in the twenty-first century no one has yet devised a convincing way of depicting a giant dragon on a live stage. I must give Kriegenburg credit where credit is due: the dragon here was certainly the most convincing I have seen to date. He had the ubiquitous dancers lowered from above the stage embedded in a frame in the shape of a dragon’s head, colored red and complete with eyeballs and teeth, with Anger in the middle of them, providing the voice; the people within the frame seemed helpless, as if trapped there by the power of the Ring. (This had been preceded by a depiction of the dancers in a pile in the center of the stage, desperately clawing at each other to try to get on top; I assumed this was a symbolic representation of the hoard that Fafner is sitting on, the chaos representing the efforts of those who were madly pursuing it to try to steal its power for themselves.)

The final night, Götterdämmerung, was definitely the part where the staging was most effective, even if it opened a bit strangely. When the drama opens, the three Norns sing the story of the Cycle so far, and realize that the end of the world is imminent. In this production, the curtain rose on a bank of television screens showing broadcasts from contemporary news channels talking about various natural disasters. Then these were turned off, and we saw the Norns standing amidst a group of people in modern dress, many of them carrying suitcases, sitting motionless as if catatonic while men in full Hazmat suits walked around the stage, taking readings with their instruments and examining the survivors. Survivors of what was unclear – a natural or environmental disaster? War? A terrorist attack? I suppose in the end, it didn’t matter; they were victims of the modern world, that much was clear. As the Norns sang, the strands of their weaving were wrapped around the survivors like a spider’s web, showing how they were caught up in the inevitability of the world’s destruction.

After the Norns quit the scene, and after Siegfried leaves his beloved to go out and have heroic adventures into the world (when, interestingly, in the only nod to the source material I noticed in the entire drama, Brünnhilde drew runes on him for protection before he left – yes, actual runes, correctly drawn by Stemme!), we entered the world of the Gibichungs. The Gibichungs’ castle was depicted as a twenty-first century office building, made of glass and steel, with indistinguishable men and women in dark business suits busily going about their tasks. Continuing the theme of plutocracy, Gunther, Hunding, and Gutrune were depicted as the heirs of a family-owned multinational corporation. Whereas the gods had a certain elegance to them, reflecting styles reminiscent of upper-class Europe in the early twentieth century, the Gibichungs were wholly contemporary, in modern dress. When we first see them, Gunther is being fellated by one of his female servants. They were played as being wholly vile, decadent, and corrupt; Gunther – who was continually drunk – and Gutrune amused themselves by devising ways to abuse their servants, and the incestuous relationship that is only hinted at in Wagner’s libretto was made explicit here. In what was again perhaps too obvious of a symbol, a rocking horse in the shape of the Euro symbol sat at the front of the stage, which Gutrune took joy in riding. Whereas in most Ring productions, Gutrune is depicted as a shy and lonely woman who is victimized by her brothers, here she was a spoiled brat, more like Paris Hilton than a spinster noblewoman. There was indeed a medieval-style suit of armor off to one side of their castle, but it was only there for decoration – perhaps suggesting that Gunther’s line was once a noble one, but had since become corrupted and declined. This is where the staging and Wagner’s intentions were, for once, very much in synch, as this is definitely the nature of the Gibichungs as written in the libretto, and Kriegenburg brought to the fore an aspect of the text that it suggests in a much subtler way.

Later, when Hagen implored the Gibichungs to take up their weapons before the wedding feast, the office workers answered his cries, whipping out their cell phones as their sidearms. When Brünnhilde was forced to come there and then makes her angry accusations against Siegfried, the Gibichungs eagerly recorded the exchange with their phones’ cameras, and we see some of them go off to the side to make calls or send texts – phoning in the story to the tabloids, one assumes, or uploading their videos to YouTube; or perhaps seeking advice on how to deal with the situation. Not even Alberich was immune to the degeneracy of the modern world: When he came to the castle to speak to his son Hagen, he fixed himself a drink while they were chatting, and then made off with several bottles of liquor on his way offstage.

The only detail that struck me as odd, at least initially, was that Siegfried arrived in medievalesque dress, whereas everyone else was dressed in twenty-first century style – with Siegfried later changing into a suit when he is accepted as a blood-brother by Gunther. The reason for this soon became apparent, however, especially in the scene of Siegfried’s murder, where he is shown to have lost his prey on the hunt because he is drunk, brandishing a whiskey bottle in his hand. The meaning is clear: Siegfried begins as a “traditional” man, from another and purer age, but succumbs to the corrupting influences of the modern world. As odd as it would have seemed to him could he have seen it, I believe Wagner would have approved of the Gibichungs’ depiction here.

After Brünnhilde’s self-immolation – of which no staging, no matter how absurd, could reduce its dramatic power – the production took what was, in my view, the worst misstep of its final night. In Ring productions of recent years, it has become fashionable to show Gutrune as the sole survivor of the world-ending destruction that ends the Cycle (even though Alberich is a much more logical choice for this – as he indeed is in some productions – since he has access to occult powers and is the only one whose fate we do not know at the end from the libretto). This is clearly a feminist reading, in which the audience is asked to sympathize for the poor woman who has been used as a pawn by her brothers in their pursuit of power. This interpretation does make a certain degree of sense in more traditional drawings of Gutrune’s character, where she is portrayed as passive, yet loving of Siegfried, even if it seems a huge reduction and trite oversimplification of the many layers of meaning contained in the work as a whole to highlight her fate at its conclusion, given that she is not one of the major characters. But in this production it makes no sense whatsoever given that it went to extreme lengths to show Gutrune as nasty and selfish. At the very end, as the final notes were being played, the dancers returned once again, dressed all in white, and joined hands, surrounding Gutrune at the center of the stage and comforting her in her grief (I was reminded of those “feels” memes that have been going around for a while). How are the feelings of a spoiled brat related to anything significant in the many strands of meaning that run through the Ring? It really made no sense and seemed to be nothing more than Kriegenburg trying to win over the critics by contriving a politically-correct ending.

There is nothing particularly new in the ideas that underlay Kriegenburg’s production; for the most part, it just seemed like a more heavy-handed exploration of the anti-capitalist reading that has been commonplace among productions of the Ring since Chéreau’s in 1976. It’s understandable why this view of it is in vogue, since the socialistic and anarchistic side of Wagner is much more palatable to today’s cultural elite than the other aspects of Wagner’s work. If opera companies want to eschew traditional presentations of the Ring, very well, but then they should at least try to break new ground. What about its psychological aspects, to give but one example? Wagner was very much a forerunner of Carl Jung in the way he looked at myth, and much could be made of that in an unconventional Ring. That being said, this production did work at times, even if it failed miserably at others.

Despite its many shortcomings, the performances given by all the singers – apart from Koch’s – were memorable. The orchestra, on the other hand, was for the most part adequate, but one heard a few grating flubs from time to time. Russian-born conductor Kirill Petrenko sometimes took the tempo at a breakneck pace – I personally prefer a somewhat slower pace, which allows one to take in the music and the drama more fully. I will add as an aside that, generally speaking, I prefer the sound of American orchestras in opera music to European ones. For whatever reason, American musicians seem to have a greater ability to bring bombast or lyrical intensity to the music when needed, whereas Europeans often prefer a more subdued approach.

All of my criticisms aside, there is something special about seeing the Ring in Germany, with a largely German cast, most especially in Bavaria, which is after all where it was first performed. Wagner himself wasn’t Bavarian, but there is something Bavarian in the tone of the Ring – there is warmth and passion, deep romance, and sometimes humor, all elements that one doesn’t usually associate with the stereotype of the icy Teutonic mentality. And I did detect something of a Bavarian flavor – a flavor of beer and Lederhosen – to this production, perhaps because many of its cast were locals. And it’s always a pleasure to lose oneself in Wagner’s world for an entire week – one of the most immersive experiences in cultural history, to be sure.

If you’re not too conservative in your Wagnerian tastes, you will surely enjoy seeing this production if you have the opportunity, simply because it is the Ring. If you are, then it’s probably best to stick to your DVDs for the time being.