Apathy & Fake News:

The Murder of Kitty Genovese

Posted By

Adna Bertrand Rockwell

On

In

North American New Right

| Comments Disabled

The Witness (2015)

Directed by James D. Solomon

Before working out at the gym became my religion, I grew up attending church every Sunday. The first sermon I recall hearing was related to the “apathy” of those New Yorkers who were in their apartments overlooking a street where a 29-year-old woman named Kitty Genovese was murdered on a cold, dark night. Fighting “apathy” was, according to our minister, a big moral deal and meant all sorts of politically correct moral things that I’ve now come to believe are not so moral. The morality tale resulting from the murder of Kitty Genovese regarding “apathy” was created in a now-classic New York Times article [2] dated March 27, 1964. The article leads off with the alarming line, “For more than half an hour 38 respectable, law‐abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew Gardens.”

Kitty Genovese’s murder and the alleged apathy of her neighbors impacted American society like a well-aimed barrage of eight-inch artillery shells [3]. Television programs referred to the events for decades, even altering the details to imply the neighbors callously went out of their way not to get involved. The original [4] Death Wish [5] alludes to the Genovese murder when Paul Kersey pulls down his window shades rather than stop a mugging of a woman outside his apartment complex. For the next two decades, every few years, reporters would track down a Kew Garden witness and attempt to carry out an interview-by-ambush. The murder was the inspiration for a theory called the “bystander effect [6].” According to this admittedly plausible theory, one is more likely to get help if there are fewer people around rather than more.

The actual events of the murder are unearthed in the 2015 documentary film, The Witness, which presents findings in the case by Kitty’s brother, William Genovese. William lost both legs while serving in the US Marine Corps in Vietnam. Will’s decision to volunteer for ‘Nam was based on his desire to fight against “apathy.” After watching this documentary, this author realized that instead of an inguilting morality tale about “apathy,” the story around Kitty Genovese’s murder should really be interpreted as a call for further white advocacy.

A more accurate view [7] of the Kitty Genovese murder first bubbled up into the public consciousness in 2004, when an amateur historian named Joseph De May, Jr. decided to create a historical Website about the Kew Gardens apartment complex, where he lived. In doing so, he was forced to examine the area’s most notorious crime. After reading the original New York Times article, De May realized that the story presented therein was not accurate [7]. The inaccuracies began in the first sentence. De May was able to prove that there were two attacks on Kitty, not three. Additionally, one resident had shouted at the killer from his window, causing him to temporarily flee. Kitty walked away, and the person who had shouted assumed the attack had been thwarted.

Assuming it was not completely invented by the New York Times, the idea of “38 witnesses” probably comes from a list of names of those the police interviewed as part of their investigation – not people who saw anything during the attack. At any rate, the records show that most witnesses heard, and did not see, something, and didn’t realize there was a murder happening. Several residents also claimed they had called the police; in 1964, however, there was not the efficient 911 system we have today. One had to dial an ordinary number, and calls weren’t recorded, either. One also had to call the police precinct responsible for the particular area where a crime was being committed instead of a central dispatch office. The Kew Gardens residents were thus ineffective, not “apathetic.”

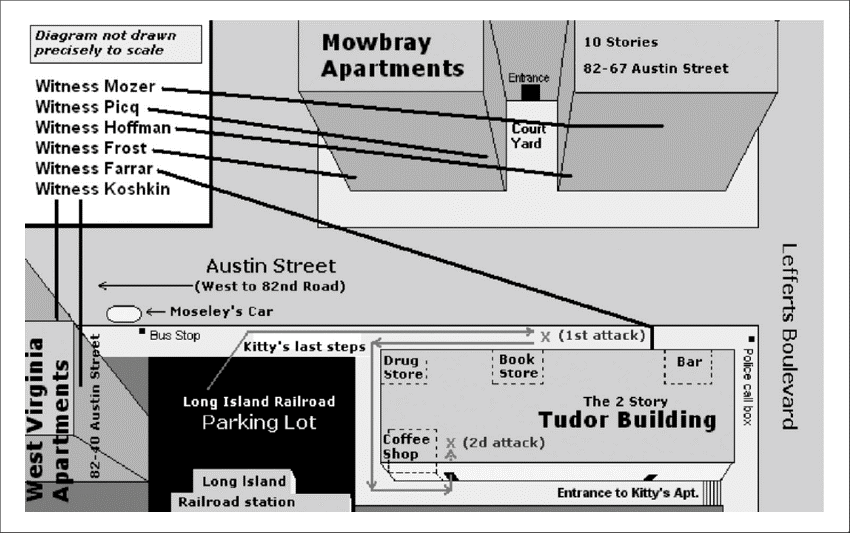

[8]

[8]The map [9] of Kew Gardens and the crime scene.

So what can a white advocate take away from both the documentary The Witness and the overall story of Kitty Genovese? The first thing that jumps out is the Jewish Question. The editor responsible for the original New York Times story was Abe Rosenthal, and the reporter who wrote it was Martin Gansberg. The Jewish aspect of this case will be further discussed below, but it needs to be mentioned up front. The second thing which jumps out is the media’s framing of the story. It appeared on the front page of the New York Times at a time when that paper still held unquestioned credibility across American society as a whole, when the news media in general was still widely believed to be a neutral, honest institution merely reporting facts. The 1964 article was intended to shape public consciousness, and was thus an example of metapolitics in action. In fact, in present-day terms, it was both metapolitics and fake news.

Although this is not discussed in the documentary, it’s possible that Abe Rosenthal and Martin Gansburg themselves could have been influenced to talk about “apathy” by contemporary pop-culture works. The first is The Time Machine (1960). In this film, the blondish Eloi sit passively while a woman in danger screams for help [10]. The second, more directly applicable film is the Alfred Hitchcock classic, Rear Window (1954). In a scene which moves the plot to its climax [11], a woman whose dog has been killed by the movie’s antagonist cries out, “Which one of you did it? Which one of you killed my dog? You don’t know the meaning of the word neighbors. Neighbors like each other, speak to each other, care if anybody lives or dies. But none of you do.”

[12]

[12]“Apathy” didn’t kill Kitty Genovese, an Afro did. Kitty Genovese’s murder should have been a teachable moment about black crime and the destruction of America’s cities.

Lost in all the shouting about “apathy” is what President John Quincy Adams’s grandson Charles Francis Adams, Jr. called [13] “The Everlasting Nigger-Question [14].” Kitty Genovese was slain by a black serial killer and life-long criminal, also 29, named Winston Moseley. In a just world, the message of Kitty Genovese’s murder should not have been “apathy,” but a teachable moment about the escalating black crime wave across the great cities of the North. Which brings us back to the Jewish Question. It is a well-known fact that Jews supported black aspirations during the “civil rights” revolution of the 1960s – which was a black revolution, not a campaign for “rights.” In order to advance “civil rights,” newspaper creators suppressed the facts about black crime. The story of “apathy” was a look-the-other-way dodge to keep popular support for the Jewish-led MLK/desegregation efforts going.

One aspect of black crime which is plainly demonstrated in this movie is the black community’s inability to self-police through effective moral instruction or moral action. In a very tense scene, William Genovese meets with Winston Moseley’s son, who is a minister. The killer’s black, preacher-man son believes that his father “snapped out” of his evil later in life and insists that Kitty had used “racial epithets” towards his father, thus deserving to be attacked. The black preacher-man has a hard time pronouncing the word “epithets,” and there is a sense that he is using a word he doesn’t fully understand. Regardless, even if Kitty had used racial epithets against Moseley, this did not give Moseley the right to stab her to death in two separate attacks. This should be an important lesson regarding the black community – even their ministers can’t morally police themselves or their community. Christianity [15] has made no impact upon blacks.

[16]

[16]This famous photo of Kitty Genovese from 1961 is a mugshot. Kitty was the manager of a bar and was arrested in an anti-gambling sweep.

Another thing one can sift out from this documentary is the idea that crime – meaning black crime, of course – was already bad in America’s cities by the 1950s, contrary to the myth of an American ’50s whitopia. Because of what was going on, all the Genovese family but Kitty had left New York City for Connecticut in the 1950s. Since discovering Counter-Currents and reading many of its articles, I’ve come to conclude that African pathology didn’t arise in the 1960s, as is popularly believed. It has always existed. There has never been a time since the end of slavery when the black population was anything more than a menace to the whites who live near them.

Part of the viral reaction to Kitty Genovese’s murder was the fact that she was a “you go girl” trying to “make it on her own [17].” The documentary shows that Kitty had been briefly married to a man, but that after their annulment, she had moved in with another woman in a “Boston Marriage [18]” arrangement (today she has been declared a lesbian). With that in mind, Kitty’s death underscored the old truths that nothing good happens to someone who is out and about after midnight, and that a woman away from her adult male relatives is especially vulnerable. It is not a coincidence that the horror genre [19] of film really took off in the 1960s, and that most of the genre’s fans were, and still are, women [20]. It remains to be seen for just how long the horror show of Africans living in the great cities of Western Civilization will continue.

The final notable thing about this film is the clear sympathy that Shannon Beeby showed for William Genovese after she acted out Kitty’s final moments. I can’t be certain exactly what Shannon Beeby’s heritage is, but Beeby [21] is an English name, and variants of this surname can be found in the genealogy books of the first New England Puritan settlers [22]. During the nineteenth century, there was considerable tension [23] between native-born Protestant whites with names like Beebe/y and Catholic immigrants from Europe such as the Genovese family. Indeed, American Protestants in the Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s saw blacks as being less alien than Catholics. It is clear, however, that this situation has long since ended. All whites are in this together, no matter how many sacraments you think is the right number. We’re all Kitty Genovese.