An Esoteric Commentary on the Volsung Saga, Part II

Posted By Collin Cleary On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled3,283 words

Part I here [2], Part III here [3]

Chapter 2. Concerning Rerir and His Son Volsung

In the previous chapter, we saw that Sigi, the son of Odin, is the first step in the god’s master plan: the creation of a new race of super-warriors, who will come to be known as the clan of the Volsungs. In order to become a truly great warrior, Sigi must transgress man’s laws and remove himself from society – entering the wilderness where he will live as his own master and create a world of his own. Thus, Sigi is outlawed for killing a slave who had outshined him in hunting. I argued in the last installment that Odin either orchestrates this event, or allows it to happen (it comes to the same thing). Once Sigi has been banished, Odin repeatedly rewards him. He accompanies Sigi on raids, gives him an army and ships, and makes him victorious in battle. Sigi is able to claim a kingdom for himself. He marries well and his wife gives him a son named Rerir, who “was already a large and accomplished man at a young age.”

But we know that Odin is a fickle god. He raises men up only to abandon them later. This is all very deliberate on the god’s part: He is building an army of the dead in Valhalla, the Einherjar. And for this purpose, he needs the best warriors. Thus, he favors certain promising men (in this case, actually sires one), and nurtures them, insuring that they receive training and experience that will mold them into formidable fighters. And he provides them with the means to advance from one victory to another, accumulating ever greater glory. Then, just when these men feel assured that they are invincible and always to be favored by the god, Odin turns on them – he allows them to be killed so that, having reached their peak, they may join his army in Valhalla.

And this is just what happens with Sigi in Chapter Two. Sigi grows old. He acquires many enemies, as all great men must. Finally, however, he is betrayed by men he had trusted: his own brothers-in-law. These men ambush Sigi and murder him and his retinue. As we will see, there are certain elements in the Volsung Saga that appear a number of times. One of these is betrayal by kin. This will occur again, much more famously, in the story of Sigurd, and elsewhere in the saga.

Upon his father’s death, Rerir claims the kingdom as his own and then raises an army to seek vengeance against his uncles. Now, what the text has to say here is interesting. We are told that Rerir does this because “they had betrayed him so severely that their kinship was now invalid.”[1] [4] This clearly implies that killing kin was considered taboo (as I noted in Part One, raiding and murder were considered permissible by the Germanic tribes, so long as the victims were not one’s own kin, or members of one’s tribe). In this case, however, Rerir simply decides on the authority of his own judgment to lift this particular moral prohibition. Once more, we see a Volsung transgressing a significant moral and social rule. We are then told that Rerir did not stop until he had killed all his relatives who were complicit in the murder of Sigi. And, to reinforce the shocking nature of this transgression, the text says that he did this “even though such a slaughter of near relatives had until then been unheard of in every way.”[2] [5] This transgression of moral norms, sometimes taking genuinely horrific forms, is a recurring characteristic of the Volsungs throughout the entire saga.

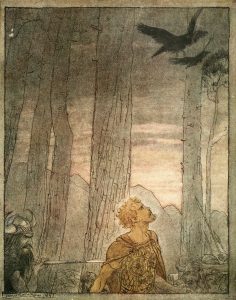

Despite this, Rerir becomes “an even greater man than his father had been.”[3] [6] In other words, he is rewarded for the slaughter of his relatives. Once again, we sense the hand of Odin at work. But all is not entirely well with Rerir. Though he has all his father’s and his uncles’ lands and riches, and a wife who is worthy of him, somehow he and his Queen cannot conceive a child. We are told that they pray repeatedly to the gods to grant them a son. Frigg hears their prayer and then informs Odin, “who was not in any doubt about how to help.”[4] [7] He summons Hljod, one of his Valkyries and the daughter of the giant Hrimnir, and gives her a magic apple. Turning into a crow, she flies off to Rerir’s kingdom and finds the King sitting on a burial mound. She drops the apple in his lap, and somehow Rerir knows what he should do with it. He returns home to the Queen and then he eats some of the apple. A short time later, the queen is pregnant. (Presumably, they had intercourse after Rerir ate the apple.)

There is more here than meets the eye in this quaint tale. First of all, let us ask which one of the pair is infertile, Rerir or his Queen. The text provides us with an answer to this question, if we read between the lines. When the apple arrives, Rerir is depicted as sitting on a howe, a burial mound. It is a well-known fact that our ancestors practiced the custom of sitting on a howe in order to increase fertility.[5] [8] Since Rerir is doing this, the suggestion is that he believes that he is responsible for the couple’s inability to conceive. Further, the text states clearly that Rerir is the one who eats of the apple.[6] [9]

Now, why would Rerir believe that he is the one who is infertile? Here we must infer, which is not difficult, the criteria by which such matters would have been decided in the time of the saga. In cases where the man was potent and the couple could not conceive, the woman would be assumed responsible, as there was no knowledge of “sperm count.” The only conceivable circumstance in which the couple would think the man responsible is if he were impotent. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that Rerir sits on the howe to try and restore his potency, and that when he eats the magic apple, this is accomplished.

But this is obviously a very strange situation. How does Rerir’s impotence serve Odin’s ultimate purpose of seeing the Volsung clan increase and flourish? Obviously Rerir’s condition is completely at odds with Odin’s aims – and so we sense, perhaps, the intervention of some other, contrary force in the matter. Could Rerir’s impotence be a punishment visited on him by one of the other gods? Recall that the text tells us that Frigg hears the prayers of Rerir and his Queen. It does not say that they pray to her. Indeed, it would be much more natural for them to have prayed to Freyja, who was a goddess of fertility and to whom mortals often appealed when increased fertility was desired.[7] [10] A further oddity is that Frigg does not help the couple herself with her own magical powers, but instead informs Odin. The god then does not go himself to bring help to Rerir, but sends a loyal Valkyrie disguised as a crow. (In many other cases in the saga, he intervenes in events personally and directly.)

One possible hypothesis is that Rerir has been rendered impotent as punishment for the slaughter of his mother’s family. It is possible (though this is pure speculation) that it is indeed Frigg who has punished him in this way.[8] [11] After all, surely Rerir’s crime would have offended Frigg, who is goddess of hearth, home, and familial bonds – and, by implication, goddess of the conventional morality that supports these (an aspect of her character that is artfully portrayed by Wagner in the Ring). If this is true, why does she tell Odin? To gloat, perhaps? In any case, Odin’s response can certainly be interpreted as subterfuge, a way of getting around Frigg and not incurring her wrath: again, he sends the Valkyrie Hljod in disguise to deliver the apple, rather than going himself.

Regardless, whether or not this theory is correct, we do feel the need of an explanation for Rerir’s impotence, since it is obviously so contrary to Odin’s plans. However, there is another, somewhat simpler hypothesis: perhaps Odin himself makes Rerir impotent because the god wants to inject his own seed, as it were, once more into the bloodline, to further strengthen it. Perhaps this is what is delivered in the apple. Eating it, Rerir impregnates his Queen with Odin’s seed, not his own. (In a later installment of this series, I will argue that something like this occurs again at the wedding feast of Signy and Siggeir, when Odin appears and plunges a sword into the tree Barnstokk.)

What occurs next in the story is equally peculiar. The Queen becomes pregnant, but the pregnancy lasts “an unusually long time.”[9] [12] In fact, the text tells us a little later that it lasts for six years! Unusual births and strange gestations are relatively common in myth and folklore. In the Mahabharata, Queen Gandhari’s pregnancy lasts an unusually long time. Hearing that Queen Kunti has given birth to the Pandavas, Gandhari begins beating her abdomen until a kind of grey ball emerges out of her. The sage Vyasa divides the ball into 101 parts, and then places the fragments into 101 earthenware jars, where they grow into Duryodhana and his 99 brothers and one sister.

These long gestations clearly suggest that something very special is growing – something great, something that takes a great deal of time. This is certainly true in the case of Rerir’s Queen, for she gives birth to Volsung, the character from which the entire clan takes its name. When he emerges from the womb, he is “already very big.”[10] [13] We are told, further, that he kisses his mother before she expires from the ordeal – something that would only seem possible if he had already attained a degree of mature awareness. Meanwhile, Rerir is away in battle. He becomes sick and dies of an illness, though he had “intended to join Odin,” the text says.[11] [14] (Only men who die violently may join the Einherjar in Valhalla.) Though Odin has lost a Volsung, Rerir’s son will be ample compensation.[12] [15]

There is a general scholarly consensus that the name “Volsung” means “stallion phallus.” Jackson Crawford buries this odd and somewhat embarrassing fact in a footnote:

Old Norse names ending in –ung are typically designations for families and not for individuals, so it is likely that the original name of the individual Volsung was Volsi, and that his name was extended later to match the name of the family named for him. This is supported by the fact that his son Sig(e)mund is called a Wælsing (= Old Norse Volsung) in Beowulf, as well as simply “son of Wæls,” an Old English cognate of the Old Norse Volsi. The name Volsi occurs in one place in Old Norse literature, in a story about the Norwegian king Ólaf Tryggvason in the manuscript Flateyjarbók. There, the name is applied to a stallion’s preserved phallus that is worshipped by a pagan family. “Phallus,” perhaps specifically “stallion’s phallus” may well be the name’s original meaning (the same root is found in other words for cylindrical objects), and the name of Volsung and his family might then have evoked the virility of a stallion.[13] [16]

The juxtaposition of Rerir with Volsung could not be more striking: the impotent father is followed by his diametrical opposite, the son called “stallion phallus.” And Volsung certainly is virile: he produces eleven children. Ten of these are sons, and there is one daughter. The eldest son, Sigmund, is also the twin of the daughter, Signy.[14] [17] (The other children are not named in the story.) The saga writer tells us that Sigmund and Signy were the “foremost” and “most beautiful in every way” of Volsung’s children, but that “All of Volsung’s children were great.”[15] [18]

The proliferation of males also seems to be an expression of Volsung’s virility. We might ask (since this is likely a work of pure fiction), why not eleven sons and no daughter? It is significant that this daughter is the very first female Volsung – and we would not go wrong in assuming that she comes into the world to serve a very special purpose (a purpose, of course, that suits Odin’s plans). Those already familiar with the events of the saga, of course, know that this one daughter is necessary to produce the next generation of Volsungs.

In addition to sexual virility, Volsung is an all-around paragon of masculine virtue. “He grew big and strong at a young age, and he was very bold in every kind of deed that requires manliness and courage. He became a very great warrior, and he was victorious in his battles.”[16] [19] We have already seen Sigi and Rerir described in similar terms. As I noted in the last installment, each generation of Volsung seems to be bigger, stronger, braver, and more virile than the last. Thus, the text informs us that Volsung’s children were “the greatest of all those mentioned in the ancient sagas, the greatest in wisdom and in all sports and all kinds of combat.”[17] [20]

Stephen Flowers notes that in the sagas generally, it is often later generations of a family that exhibit real greatness.[18] [21] This also makes sense in terms of the complex and mysterious Germanic conception of “the soul.” If one can acquire more than one fylgja (“guardian spirit”), which strengthens the kynfylgja (the fylgja of one’s clan), and if the hamingja (“luck”) is fed by heroic deeds, then clearly something builds or grows across several generations. (See Part Two of my essay “Ancestral Being [22]” for more information on these concepts.) The members of the clan are the unfolding of what the clan is – the flowering of its potentialities. The full flower of the Volsungs, of course, is Sigurd, who is not only the bravest and strongest of warriors, but so tall that when he walks through a field of full-grown rye, “the bottom point of his scabbard would touch the top of the plants.”[19] [23]

The mother of Volsung’s children is none other than the Valkyrie Hljod, who had delivered the magic apple to Rerir. She is “sent” by her father, the giant Hrimnir, to wed Volsung once he reaches maturity. There is something oddly “incestuous” about this union, given that the Valkyrie had facilitated the conception of Volsung, and is much older than him. As we have seen, when Hljod delivered the apple she was acting under the orders of Odin. It is hard to believe that that is not also the case in this instance. Yes, it is her father who sends her – but all fathers “give away” their daughters. It is highly unlikely that Hrimnir sends her to Volsung for any other reason than that Odin has requested it. So, what we have in the case of the Volsung-Hljod match is a man who is very probably a child of Odin (recall that the apple may deliver Odin’s “seed”) marrying a Valkyrie, who happens to be the daughter of a giant. It is clear that with this match, Odin aims to produce beings even greater than Volsung. It is also plausible to suppose (though the text does not give any indication of this) that Hljod may also have been sent to play the role of teacher to Volsung – initiating him into secret knowledge held only by the gods and the giants. Later in the text, Brynhild plays such a role to Sigurd.

In any case, after establishing himself in the world as a great King and father of a large brood, Volsung builds a “magnificent hall” around an immense tree whose branches weave about the beams of the roof. In the present chapter, it is described as an oak, whereas in the following chapter it becomes an apple tree. This could reflect the Icelanders’ use of “oak” (eik) as a general term for tree, or the saga writer’s reliance on different sources. The more symbolically “authentic” choice is clearly the apple tree, for we have seen an apple playing a major role already in the continuation of the Volsung clan. The name of the tree is Barnstokk, which can be translated “child tree” or “family tree.”[20] [24] All of this obviously points to the conclusion that the tree represents the Volsung clan itself.

H. R. Ellis Davidson notes that “we have here an example of the ‘guardian tree,’ such as used to stand beside many a house in Sweden and Denmark, and which was associated with the ‘luck’ of the family.”[21] [25] She then cites some actual historical examples of houses built around trees. However, this was by no means a common practice (so far as we know), so this detail in the saga is striking and cries out for interpretation.

Symbolically, a tree contained within a hall represents the constraint or confinement of the natural by what is human or social. In Volsung’s eyes, building the hall around the tree is likely an act of protection – of safeguarding his clan, as represented by the tree and its fruit. But what we find in the next chapter is that just as the tree is confined by the hall, its branches entangled in the beams, so has Volsung entangled his family within social ties of a highly undesirable nature. Specifically, he has married his daughter off to another king, a man she does not love and who is treacherous and dishonorable. And all of this was arranged, no doubt, with the same sort of good intentions with which he confined the tree: to safeguard his family by forming an alliance, keeping the peace, and insuring Signy’s future. As we shall see, however, Odin has different plans . . .

Notes

[1] [26] The Saga of the Volsungs with the Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok, trans. Jackson Crawford (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2017), 2.

[2] [27] Crawford, 2.

[3] [28] Crawford, 2.

[4] [29] Crawford, 2.

[5] [30] See H. R. Ellis Davidson, The Road To Hel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 105-111.

[6] [31] As R. G. Finch notes, “no other translation seems possible.” See Finch, The Saga of the Volsungs (London: Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1965), 3 (footnote 2).

[7] [32] I am aware that some scholars theorize that at some remote time, Frigg and Freyja were actually one goddess, but by the time the sources of the saga were composed, these were definitely distinct figures.

[8] [33] In Greek myth, Hera (who shares many characteristics with Frigg) curses Priapus with impotence whenever he actually tries to put his erection to real use.

[9] [34] Crawford, 3.

[10] [35] Crawford, 3.

[11] [36] Crawford, 3.

[12] [37] This sequence of events lends some support to the hypothesis that Odin deliberately renders Rerir impotent and transmits his own seed to Rerir’s Queen by means of the apple. Perhaps this King, who manages to die in his bed, was not so great after all.

[13] [38] Crawford, x. Other scholars agree. Mindy McLeod and Bernard Mees note that volsi is slang for “penis,” derived from vǫlr, meaning “rod.” This is in turn related to Modern Norwegian volse “thick, long muscle, thick figure,” Icelandic völstur “cylinder,” dialectal Swedish volster “bulge,” Old High German wulst “bulge,” and the English dialectal word weal meaning “penis.” See McLeod and Mees, Runic Amulets and Magic Objects (Rochester, N.Y.: Boydell Press, 2006), 104. For information on the story in Flateyjarbók see the Wikipedia entry on Völsa þáttr [39].

[14] [40] Sigmund literally means “victory protection” and Signy means “new victory.” It is my view that an analysis of the names in the saga does not reveal much.

[15] [41] Crawford, 3.

[16] [42] Crawford, 3.

[17] [43] Crawford, 3.

[18] [44] See Stephen E. Flowers, Sigurðr: Rebirth and the Rites of Transformation (Smithfield, Tx.: Rûna-Raven, 2011), 70.

[19] [45] Crawford, 41.

[20] [46] Crawford, xi.

[21] [47] H. R. Ellis Davidson, “The Sword at the Wedding,” Folklore 71:1 (March 1960): 1-18; 4.