The Englishness of Nick Drake

Posted By Fenek Solère On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled‘I never felt magic crazy as this

I never saw moons knew the meaning of the sea

But now you’re here

Brighten my northern sky’

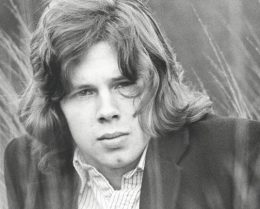

Born into old-money and brought up amidst the rural charm of a rambling red brick house named Far Leys in a small sleepy hamlet called Tanworth-in-Arden on the outskirts of Birmingham, Nick Drake’s childhood home on Bates Lane looked out over Vicarage Hill towards the winding River Alne. Where not so long before, just like in Tolkien’s idyllic Shire, the great wooden wheels of watermills ploughed white water between the grassy banks as it flowed southwards past Wootton Wawen. Wootton itself, old even when the Doomsday Book was compiled, being a settlement that Aethelbald, King of the Mercians, gave to Earl Aethilric to build a minster somewhere between 723 and 737.

The fledgling songster growing up in the very heart of Aethelred and Aethelflaed’s ancient Saxon Kingdom, before going to Eagle House Preparatory School in Berkshire and boarding at Marlborough, buying his first Levin guitar for £13.00 in a local shop and writing songs in the vein of an archetypal English troubadour and mystical romantic about unobtainable princesses like “The Thoughts of Mary Jane”:

‘The way she sings

And her brightly coloured rings

Make her the princess of the sky’…

as well as the classic “Time Has told Me”:

‘Time has told me

You came with the dawn

A soul with no footprint

A rose with no thorn’…

and the Edward Elgar inspired I Was Made to Love Magic:

‘I was born to love no one

No one to love me

Only the wind in the long green grass

The frost in a broken tree

I was made to love magic

All its wonder to know

But you all lost that magic

Many many years ago

I was born to use my eyes

Dream with the sun and the skies

To float away in a lifelong song

In the mist where melody flies.

I was born to love magic…

I was born to sail away

Into a land of forever

Not to be tied to an old grave

In your land of never.

I was born to love magic…

Was made to love magic’…

Precocious adolescent lyrics one may argue but words imbued with themes of Anglo Saxon Ring-Lore, Star-Cunning and Wyrd Craft. The artist constantly invoking what the Anglo Saxon scholar Stephen Pollington calls ‘All our hardiest words — mother, father, land, earth, tree, field, sky, love, hate, live, die, eat, drink, sleep and wake’. A true son of Saint George conjuring haunting, if subliminal, images of sacred groves, revered springs, elves, demons and fairies. Much like the expression Pink Moon itself, no doubt consciously or unconsciously influenced by the proximity of the aptly named Pink Green, source of the River Alne near Wood End.

Such intimate topographic detail coming to characterize Drake’s musical compositions for the whole of his short but artistically productive life.

Academically successful, ‘though distracted’, while boarding in the Wiltshire downs, within earshot of Silbury Hill, the tallest prehistoric man-made structure in Europe, he spent the summer before going up to Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, studying French in Aix-en-Provence, busking in the centre of Aix on weekends, experimenting with hallucinogenic drugs and driving around North Africa with vagabond friends.

Slowly he was metamorphosing into the poet in black, writing songs about the moon and the seas like Bird Flew By, Milk and Honey and Blossom Friend. Descriptions reminiscent of the Lacnunga, a collection of medical and magical texts from the tenth century, which Dr. Brian Bates, former Research Director of the Christensen Foundation’s project on recovering the nature-based knowledge of ancient England and author of the Way of Wyrd (1983), The Wisdom of the Wyrd: Teachings for Today from Our Ancient Past (1996) and The Real Middle-Earth (2002) believes were shamanic, involving music, dance and the ingestion of certain plants and mushrooms in order to enter a trance-like state to receive guidance and healing.

Certainly, the symbolism and the word-play of Drake, the would-be 1970’s minstrel, brings to mind the Nine Herbs Charm and the Land Ceremonies Charm which was often used to promote the fertility of the soil. So much so that you can practically smell the fragrance of night scented stock, wild thyme, plantain, fennel and crab apple in his pastoral vignettes, a symphonic blending of vocal tone and chord textures like that used in “Bird Flew By”:

‘Bird flew by

And wondered, wondered why

She was wise enough to stay up in the sky

From the air she could wonder

For a reason

What’s the point of a year

Or a season’…

And in “Milk and Honey”:

‘Round and round the burning circle

All the seasons: one, two and three

Autumn leaves and then the winter

Spring is born and wanders free

Gold and silver burns my autumns

All too soon they’d fade and die

And then I’d known, there’d be no others

Milk and honey were their lies’…

And again in “Blossom Friend”:

‘Black days of winter all were through

The blossoms came and they brought you

Clouds left the sky

And I knew the reason why

They made way for you and the blossom

The seasons cycle turned again

An April shower now and then

Trees came alive

And the bees left their hive

They came out to see you and the blossom

People were laughing, smiling with the sun

They knew that summer had begun

The nights grew warm, the days grew long

Spring turned to summer and was gone

It seemed so fine

All the cider and wine

But I knew you’d go with the blossom

When the Spring returns I’ll look again

To find another blossom friend

Until I do

Find something new

I’ll just think of you and the blossom’…

Affectation some cynics might claim but the six foot three giant, walking with shoulders hunched in his shabby lace up shoes, ill-fitting jacket and black corduroy trousers, pulled it off with incredible aplomb according to the popular opinion of the time. Maybe it was the beautiful hands that one girlfriend so fondly recalled years later? Or maybe it was the schoolboy exploits like driving out to the Suffolk coast, listening to the sound of the waves pounding on the shingle, bringing forth visions of the thrusting oars of King Raedwald’s ships as they furrowed the estuaries and nesses off the Anglian coastline?

One can only guess at the sort of inspiration the chirruping curlew calls may have had on such an impressionable mind. Lost amid a foggy lowland that had provided the scenic backdrop to some of M. R. James’s most eerie tales and witnessed longboats being run aground at Caister-on-Sea, Snape Common near Aldeburgh and Woodbridge, bringing Pagan war-bands ashore, before being carried to the top of a hill to host the funereal treasure horde at Sutton Hoo.

Such acts impregnating the very earth itself with unmistakable heathen Englishness.

And it was the descendants of those same Anglo Saxon peoples who populated places like the recently discovered Royal Hall at Rendlesham that many centuries later constructed Cambridge’s Gothic colleges, where Drake sat down to write in the shadow of bells and spires, that once looked down on the first tentative intellectual steps of the poet Christopher Marlowe at Corpus Christi, the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell at Sidney-Sussex and author of Paradise Lost, John Milton, at Christ’s College.

Drake unsurprisingly studied English literature and was particularly drawn to the works of William Blake, Henry Vaughan and William Butler Yeats. Influences reflected in his own highly original lyrical output. Like Blake, Vaughan and Yeats, Drake also skillfully uses elemental symbols and mystical codes, largely drawn from nature. The stars, rain, sky, mist and seasons are all common-place in his oeuvre, no doubt reflecting his rural upbringing and rootedness in the country of his birth.

Blake’s words in ‘To See a World’ from Auguries of Innocence:

‘To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an Hour’

would certainly not be out of place in a Drake melody. Neither would the symbiosis of Christianity and pagan metaphor through the medium of the landscape and nature as per Henry Vaughan’s “Regeneration”:

‘It was high-spring, and all the way

Primrosed, and hung with shade;

Yet, was it frost within,

And surly winds

Blasted my infant buds, and sin

Like clouds eclipsed my mind’

Or even, W. B. Yeats’s, as in his most famous poem “The Second Coming”:

‘Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things apart; the Centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world…’

Similar sensibilities as these being crafted into songs on Drake’s three original albums, Five Leaves Left (1969), Bryter Layter (1971), and Pink Moon (1972). Indeed, iconography related to the spring and summer seasons are especially evident in the song-smith’s early work like “Way to Blue,” “The Thoughts of Mary Jane,” and “Saturday Sun”:

‘Have you seen the land living by the breeze

Can you understand the light among the trees

Tell me all you may know

Show me what you have to show

Tell us all today

If you know the way to blue?’…

‘Who can know

The thoughts of Mary Jane

Why she flies

Or goes out in the rain

Where she’s been

And who she’s seen

In her journey to the stars’…

‘Saturday sun

Came early one morning

In a sky so clear and blue

Saturday sun

Came without warning

So no one knew what to do’

Yet from Bryter Layter on, the descriptions he deploys in songs like Things Behind the Sun, Place to Be and Pink Moon, coupled with the trademark complexity of his guitar tunings are far more bleak, deliberately evoking the fall and winter, which of course are more often than not used to convey a sense of loss and sorrow. Such as:

‘Don’t be shy you learn to fly

And see the sun when day is done

If only you see

Just what you are beneath a star

That came to stay one rainy day

In autumn for free’

Complimented by “Place to Be”:

‘And I was green, greener than the hill

Where flowers grew and sun shone still

Now I’m darker than the deepest sea

Just hand me down, give me a place to be’

and the triptych completed by the ominous “Pink Moon”:

‘I saw it written and I saw it say

Pink Moon is on its way

And none of you stand so tall

Pink Moon gonna get you all

It’s a pink moon

It’s a pink moon

Pink, pink, pink, pink

Pink moon’

After all, it is said Cambridge nurtures melancholy with its long grey days and dimly lit courts leading onto the city’s labyrinthine tangle of medieval streets. Perhaps this was a factor in Drake’s mindset at the time? Or possibly it was Nick’s obsession with musical authenticity? Following in the tradition of Keats, Vaughan Williams and Frederick Delius, as the very personification of Englishness itself ? For part of the English Romantic tradition demands that one appears to be partially sad even when being celebratory. In a sense, celebrating what one is commemorating. A perfect example being Ernest Dowson’s elegiac poetry “Songs of Sunset” which Delius set to music:

‘A song of the setting sun!

The sky in the west is red,

And the day is all but done:

While yonder up overhead,

All too soon,

There rises, so cold, the cynic moon.

A song of a winter day!

The wind of the north doth blow,

From a sky that’s chill and grey,

On fields where no crops now grow,

Fields long shorn

Of bearded barley and golden corn.

A song of a faded flower!

T’was plucked in the tender bud,

And fair and fresh for an hour,

In a lady’s hair it stood.

Now, ah, now,

Faded it lies in the dust and low’…

With Drake replying in kind:

‘’When the day is done

Down to earth then sinks the sun

Along with everything that was lost and won

When the day is done’

Certainly Drake’s songs, much like his pale face in the remaining black and white photograph memorabilia, are wreathed in smoke rings of grey-blue depression. Arthur Lubow on the liner notes to the 1996 Fruit Tree compilation describing them as “disturbingly pure and innocent, like the chilling loveliness of a boy’s-choir singing Faure’s Requiem”. Another critic commenting that they seemed to be a “series of extremely vivid, complete observations, almost like a series of epigrammatic proverbs”.

One apocryphal story tells how Drake tried to perform at the Cambridge May Ball, backed by a dozen female string players in black evening gowns and white boas but his microphone went dead halfway through the show and he continued to sing on in splendid isolation to the disinterested accompaniment of champagne swilling undergraduates.

After leaving Cambridge some nine months before graduating Drake took up residence in London’s Notting Hill and Hampstead. Where he was ‘discovered’ and signed to the young Harvard graduate Joe Boyd’s Witchseason Productions on the strength of a recommendation from Fairport Convention’s Ashley Hutchings. Another of Fairport’s stalwarts Richard Thompson, whose wife Linda incidentally was once Drake’s girlfriend and says, “There was a magic that surrounded Nick”, described him as a loner, “a veiled figure in the corner of the room, singing songs of deceptive simplicity”. Thompson going on: “Time Has Told Me, the verse is very simple and then the chords for the bridge are really strange, quite unconventional. They’re not jazz changes. They’re not from classical music. It’s hard to find where they come from?”

In his 2018 interview for Mojo, Thompson continues: “River Man sounds easy and rolling, but it had a 5/4 time signature, and this really unusual chord sequence that you might find in the Impressionist composers like Debussy. Nick was a very underrated guitarist. Playing his own music he was quite extraordinary. He played immaculately and uniquely, on acoustic guitar, which isn’t an easy instrument to play in a flawless way. Nick had his own tunings for things, which people are still trying to figure out. He was probably influenced by Davy Graham and Bert Jansch but he was totally his own man with his own style”.

And today it is universally agreed that Drake’s style mattered. He has become one of the most influential and celebrated folk artists of the twentieth century. Some believing he is one of the most important folk singer/ songwriters to have ever lived. Though his own music is distinctively individual Nick Drake has influenced numerous musicians and songwriters ever since his all too early death.

The critic Trevor Dann argues Drake’s own influences were as varied as “avant-garde jazz, classical music, especially choral music, what we’d now call ‘world music’, and the blues”. Articles and reviews defining Nick’s music as having an underlying Baroque quality are now ubiquitous, with some writers and analysts specifically identifying the string arrangements in many of his songs and the occasional orchestral influence on his guitar work as being synonymous with that particular era and musical movement, particularly on his first album Five Leaves Left. An album that mainly consists of straightforward arrangements for guitar, drums, bass, and piano embellished by lush strings. With the exception of Way to Blue, which discards the traditional arrangement and leaves only Drake’s voice backed by a string quartet.

Most, if not all, of these commentators have despite their highly perceptive and detailed knowledge of the artist’s material, missed the key point, which is Drake’s intrinsic Englishness. No Dylan or West Coast Joni Mitchell could have produced such music. It is in some ways a sort of channeling of the past into the present to give birth to an idealized future. The songs are filled with shadow imagery of rune-masters, warlocks, dragons, land wights and hedge-riders.

Getting inside a Nick Drake song is almost like being taken on a spirit-journey into the Other-world, becoming tangled in the web of Wyrd and undergoing a ceremony or initiatory ritual where almost every aspect of the natural world conveys a message or a threat. What the Christian proselytizer Alfred the Great writing in 888, described thus: ‘What we call Wyrd is really the work of God about which he is busy every day’. Drake himself fulfilling the thousand year old Anglo Saxon Runic maxim:

‘A man shall utter wisdom, write runes, sing songs, earn praise, expound glory, be diligent daily’.

And Drake was diligent to the point of obsession. His bass lines are clear, and his melodies resonate. The official recordings’ arrangements echo Bach and Handel. Richie Unterberger, focusing his comments on Five Leaves Left, in his article on Drake for the All Music Guide asserts correctly “Drake created a vaguely mysterious, haunting atmosphere, occasionally embellished by tasteful Baroque strings.”

All the while the hum of harmony is pervasive in Drake’s songs. Basso continuos appear and re-appear in his tunes. A sensitive listener will pick-up on him thumbing out the bass line while playing the melody. Bass lines determining the harmonic direction of the song. A side effect of the strange yet carefully wrought guitar tunings which by simultaneously playing the parts of bass, melody, and harmony achieve an intervallic structure to facilitate the more difficult polyphonic passages.

Drake’s second album, Bryter Layter, is more contemporary and even experiments with jazz arrangements. Kathleen C. Fennesy saying of the work, “Bryter Layter was a small step backward…yet is nonetheless Drake at his most upbeat and accessible. It is also the least cohesive, most uncharacteristic and controversial of his three original albums”.

The third and last official recording is by far the most intimate and personal of the three. By now the despondent Drake was being truly traumatized by the mental horrors of schizophrenia as real to him as the imagined monsters of his ancestors, creatures like the cynocephali, the fire-breathing dog headed people of the Anglo Saxon Nowell Codex; the mearcstpa, or boundary-walkers of Beowulf; and the homodubius or centaurs from the blemmya manuscript of the poem Judith.

Recorded in two nights after a brief visit to Spain, Pink Moon’s eleven tracks are performed using just Drake’s voice and guitar. Lacking the big arrangements of the previous albums, his guitar work displays a continuing ornateness which belies a Baroque sensibility by means of complex chord structures and precision counterpoint. It is generally considered to be Drake’s magnum opus, filled with the sense of hopelessness that marked his last days. The songs were feverishly stark and painfully depressing as if he was striving to reach beyond the petty commercial structures being imposed on the natural eco-system within which his music existed.

Music that has subsequently been compared favorably to Van Morrison’s commercially incandescent 1968 album Astral Weeks. Yet, during the composer’s lifetime was overlooked, leading him into a tail-spin of uncertainty. The black fog of morbidity tormenting him for the next three years. His later work being “suffused with horrifying beauty” according to Arthur Lubow, particularly noticeable on the track Black Eyed Dog, where Drake’s voice rises to a scream that sends shivers down the spine.

To quote Frank Kornelussen from the liner notes to Time of No Reply, a compilation of ten previously unreleased songs and four tracks from Drake’s very last recording session:

He was the mystic of Riverman

and the doubter of Hazy Jane II.

He was the beggar of Place to Be

and the outcast of Clothes of Sand.

He was the dreamer of Northern Sky

and the nihilist of Parasite.

He was the stranger of At the Chime of a City Clock

and the searcher of Cello Song.

He was the lover in Hazy Jane I

and the jilted in Which Will.

He was the comedy of Poor Boy and the tragedy of Fly.

He was the life From the Morning, the doom of Black Eyed Dog,

The tune of Voice from the Mountain and the cry of Pink Moon

So it is strangely ironic that towards the end of his life, just when his depression seemed to lifting and while he was speaking positively of travelling back to France to write songs for the chanteuse Francois Hardy, that Nick drifted into an everlasting amitriptyline anti-depressant induced sleep while listening to the Brandenburg Concertos.

Leaving us to stand and wonder about what might have been while sheltering from a leaden English rain under a mighty oak tree in the village of Tanworth-in-Arden. Staring at a headstone beside a well-beaten path and a sign pinned to the lichen encrusted bark for all to see which reads: ‘Fans are requested to pay their respects by leaving only small tokens or flowers’. Eyes catching sight of all manner of ephemera, a harmonica, bracelets, rings, a framed picture of a girl dancing on the brow of a hill and a small damp packet of Swan rolling papers, recalling the reason Drake had called his first album Five Leaves Left.

So, returning home, mindful of the ghostly moon glow and the gloaming landscape that surrounds me, I unclip the notched neck of my Martin d-28 from the forked guitar stand and strum the opening chords of Fruit Tree:

‘Till time has flown

Far from their dying day

Forgotten while you’re here

Remembered for a while’…