Victorian Respectability

Posted By Irmin Vinson On In North American New Right | Comments Disabled“On the surface, Bram Stoker was a pillar of late Victorian respectability. . . . But just below the surface, he had something on his mind.”

The preceding sentences are from Christopher Frayling’s BBC documentary on Stoker’s Dracula, which was broadcast on A&E in 1996.

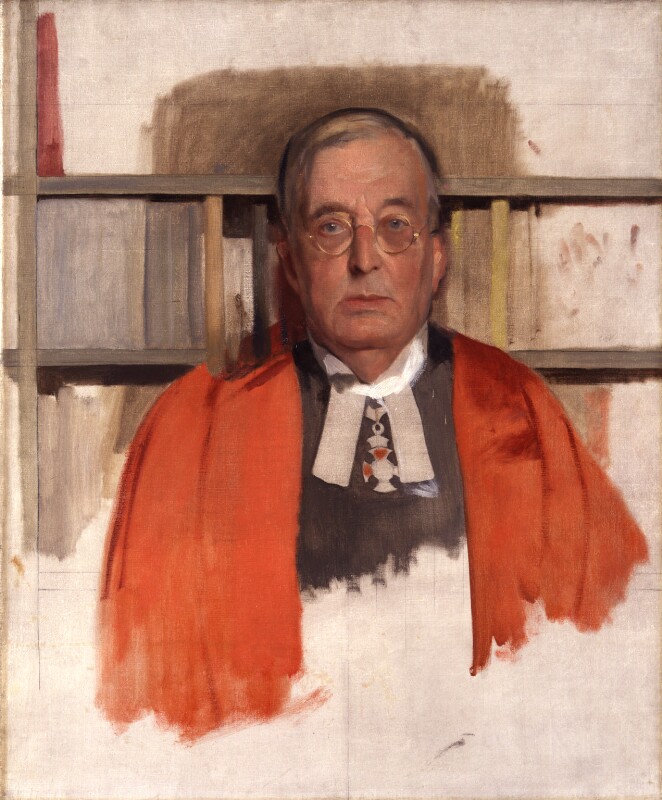

In a more recent television documentary on M. R. James, an academic best known today as a writer of ghost stories, Mark Gatiss repeats the same idea for a different author: “All these horrors were conjured up by a man who seemed the quintessentially respectable Victorian.”

Both Frayling and Gatiss are relying on a standard idea, which we could call a meme, of the repressed but creative Victorian, a pillar of society whose creativity seems at odds with his respectability, so much at odds that it is difficult to reconcile the two.

For Frayling, Stoker’s novel was fueled by “his own personal hangups and repressions.” Stoker, for example, once dreamed of three attractive women and felt attracted to them. He must, therefore, have suffered from repression in his waking hours and experienced liberation from repression in his dreams. The women would later reappear in Dracula as the three seductive vampires who beguile Jonathan Harker in Transylvania, so there is a direct link between Victorian repressions and the strange pages of Stoker’s famous novel. This link, the argument continues, is symbolically confirmed by the year that Stoker’s book was published, namely 1897, which was both “the year of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee and the year in which Sigmund Freud began his researches into psychoanalysis.”

At the peak of Victorian propriety, and hence also of powerful Victorian repressions, Freud was researching our repressions, and Stoker was exploring his own, though without understanding what he was exploring. Frayling believes the coincidence he has identified captures an important moment in time, a point of transition between the inhibited nineteenth-century past and the modern present.

The idea of the repressed but creative Victorian is a self-congratulatory meme. Frayling’s analysis, and many others like it, says almost nothing about Bram Stoker or other eminent and respectable Victorians. It is, instead, a statement of our own superior, current-year modernity: “Today we can confront the dark themes of Stoker’s novel head on, in ways he just couldn’t imagine.” We are enlightened, and Stoker was repressed, so we can understand his book much better than he could.

Stoker the Victorian is constructed as a weird specimen who is unaware that he is attracted to attractive women and can only encounter his heterosexuality through the liberation from social constraints offered by dreams. Few such men have ever existed, and Bram Stoker was not one of them.

Dracula is constructed similarly. In 1897 Freud began the project of peeling away the repressions that separated our public selves from our real selves, and Stoker was, in a different medium, unwittingly engaged in the same pursuit. Freud allowed us to look deep into our inner identities, and Stoker plunged into his own inner identity and brought back a compelling vampire story, which he couldn’t understand, given the repressions that still crippled him.

The result, many decades later, is us. We no longer need dreams to learn about the basic facts of our own biology, which were once buried under layers of repression and constraint. Dracula is an artifact produced by our quest for self-discovery, a gradual process that eventually led to our free and liberated selves in the present moment. We can now look at dark themes without flinching.

It is worth noting that no competent psychologist today takes seriously Freud’s best-known theories, such as penis envy or the Oedipus complex; but the fact that Freud is now believed to have been wrong about almost everything he discussed has not detracted from his status as a pioneer explorer of the human subconscious. He was therefore available to Frayling as a scientific analogue to Stoker the fantasy writer, though in fact belief in the Superego is no more scientific than belief in vampires.

The meme of the repressed but creative Victorian is a small part of modern culture. Only people interested in old books are likely to encounter it with any regularity. It is, however, persistent. No biography of Charles Darwin would be complete without some reference to his outward Victorian respectability, and some expression of surprise that so respectable a Victorian, burdened by various repressions, could have come up with The Origin of Species. To have described Darwin in 1850 as “respectable” would have been to pay him a compliment; to label him today as a “respectable Victorian” is to stress the limitations that his date of birth imposed on him, limitations that we are now free from.

A speaker designating a Victorian as “respectable” is also contrasting himself from inhibiting respectability. The Victorian so designated was, at best, charmingly quaint; at worst, he was filled with repressed desires struggling to come to the surface, where they could disrupt or destroy his respectability, if not transmuted into art or science. A speaker talking about Victorian respectability is saying that he does not suffer from such limitations. He is neither quaint nor repressed, and his ability to say things openly that the Victorian could not have said openly is proof of his and of our enlightened freedom.

Talk of “Victorian respectability” always compliments the present at the expense of the past. The repressed (and therefore respectable) Victorian, like the conformist suburbanite in 1950s America, serves as proof of modern enlightenment. Our creativity and self-expression are no longer, such memes tell us, constrained by the inhibiting regimes of respectability that once prevailed in bygone dark ages.

The repressed Victorian and the conformist suburbanite of Eisenhower’s America are similar ideas. Both look forward to the current year, and both locate an era in the past that we have overcome. Ideas of this sort are attractive to anyone who believes that we should take special pride in our present.

In the 1950s, the story goes, Americans endured a world of oppressive conformity, which came to an end a decade later, thanks to the colorful and liberating counterculture of the 1960s. Husbands were forced to wear gray suits and go to work in dull jobs to pay down mortgages, and bored housewives were trapped in loveless marriages and burdened by soul-killing domestic duties, like raising children and sweeping floors. That the same complaints, along with a host of new complaints, existed after the liberation does not alter the narrative, which is not really about the 1950s. All progress narratives structure the past in order to assert the superiority of the present moment.

Depending on one’s perspective, remarkable freedom is either a defining feature of our present or an illusion that our current matrix encourages us to see. There is, at any rate, apparent evidence of unprecedented freedom everywhere. We can watch any pornography we want; grotesque acts of violence are freely available in movies; I could write any formerly obscene word I choose in this essay, and nobody would fine the webmaster. Thus we are free, or much freer than we were before, because there was once a time, in the last century, when each of the preceding could be prohibited or punished.

I could also put a ring in my nose or a tattoo on my face and not feel out of place, because many others have already exercised their freedom similarly. There are magazines on newsstands devoted to their choices. My freedom is therefore visible all around me, and I can confidently look forward to a future in which whatever I feel and whatever I think can be openly presented, since increasing liberation from repression and constraint is the direction of modern history.

The truth, of course, is that every era has its own inhibiting respectability and its own distinctive repressions. Mark Gatiss is respectable today because he never dissents from current orthodoxies. In 2003 Sir Mick Jagger could be knighted for the same reason. If Britain’s decline continues, a knighthood is in Alan Moore’s future. You can be knighted in Britain for seeming dangerous, so long as you are not really dangerous, which means that you can act dangerous and rebellious but must also quietly adhere to core rules.

It is unlikely that Frayling and Gatiss ever feel the inclination to violate current rules of respectability. They are thoroughly mainstream and thoroughly respectable pillars of society, though they would think of themselves differently. But if they do occasionally repress an inner inclination to speak critically of Islam or the idea of diversity, or to question the intelligence of negroes or to oppose the political power of Jews, then they are just as repressed as any respectable Victorian who repressed an inclination to talk boldly about sex. It is disturbing, but also unsurprising, that modern freedom is conferred only on subjects and behaviors that are not deemed threatening by governing systems.

A gigantic demographic transformation is occurring in the West, and we are not allowed to talk about it publicly. The powerful people and institutions that favor the transformation do not want us to talk about it, because they fear that our talking about it could end it. Under those circumstances, any narrative that teaches that we are now remarkably free is dangerously false, even if a few of its details may be true.